By Michael Haskew

On April 18, 1942, scarcely five months after the devastating Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and other American military installations on the island of Oahu, the U.S. armed forces struck a blow against Japan that had far-reaching consequences in the outcome of World War II in the Pacific. It also bolstered American morale at a time when a boost was sorely needed.

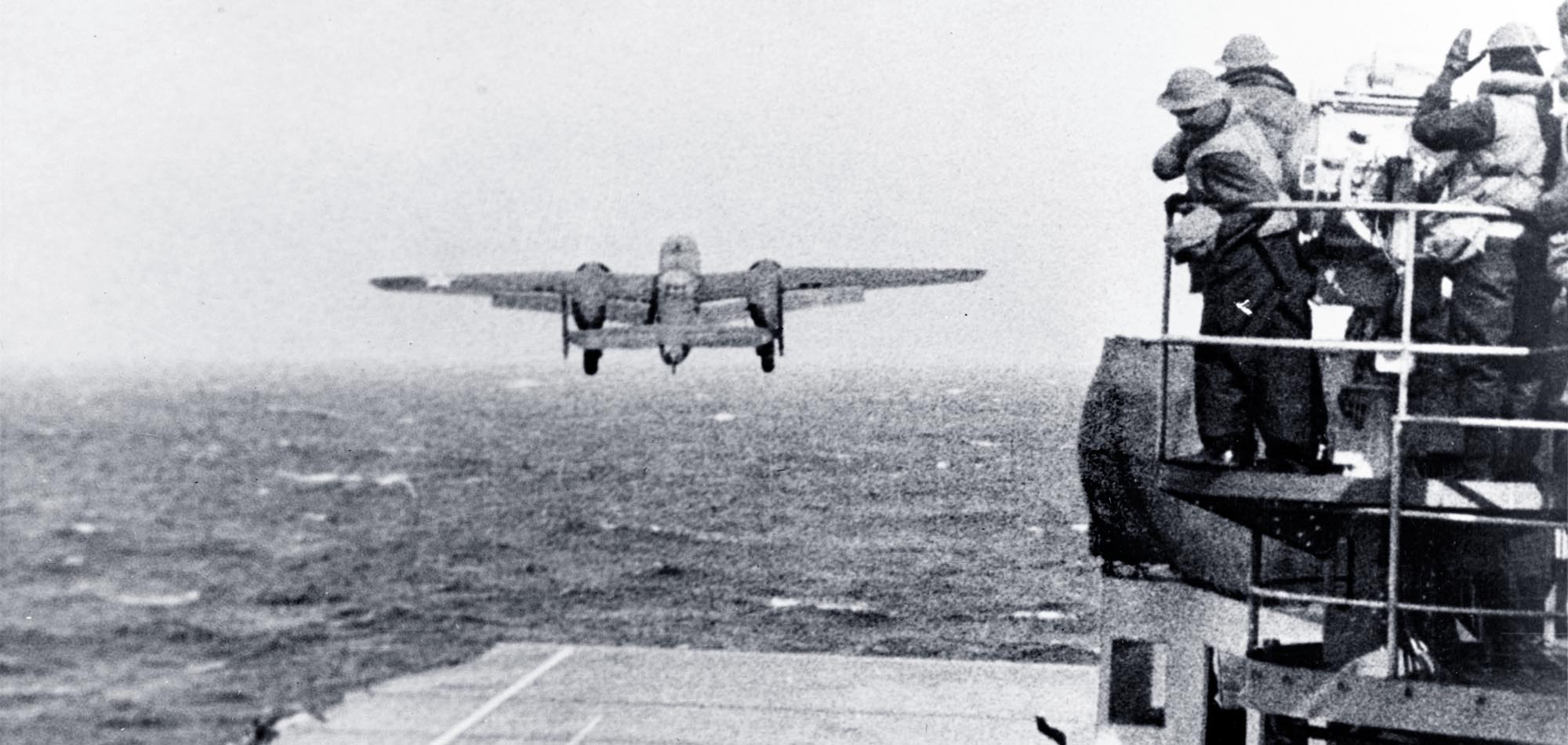

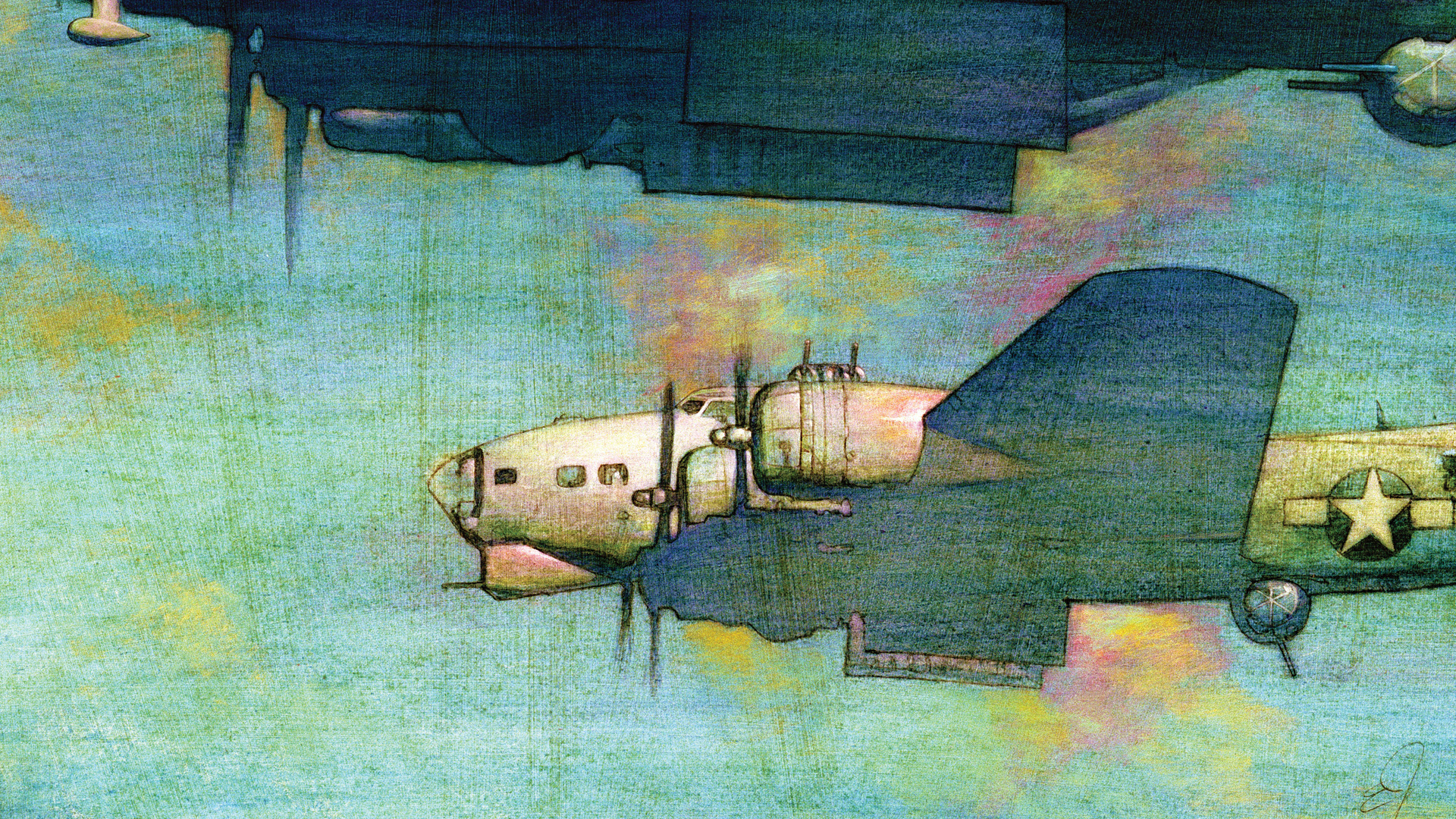

Eighty Army Air Corps pilots and crewmen flying 16 North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet bombed the Japanese capital of Tokyo. They inflicted little real damage; however, the “bombshell” that went off among senior Japanese military commanders reverberated through their strategic planning to protect the home islands from future attack and influenced the Japanese decision to seize Midway atoll to extend their security zone within 1,200 miles of Hawaii. The resulting Battle of Midway was a turning point in the Pacific War and a serious defeat for the Imperial Japanese Navy, which lost four aircraft carriers and never regained the offensive initiative.

Remembering Those Lost

Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle and the airmen under his command trained extensively at Eglin Field, Florida, to operate the land-based bombers from the deck of an aircraft carrier. During the raid itself, three airmen were killed. Eight were captured by the Japanese, and three of these were executed while a fourth died in captivity. One crew landed in the Soviet Union and was interned. Others ditched in the sea or crash-landed in China, making their way to safety with the help of Chinese troops and friendly villagers. Fifteen B-25s were lost. Doolittle believed that he would be court-martialed but instead received the Medal of Honor and promotion to brigadier general. Every man who participated in the raid was a volunteer.

For years, the surviving Doolittle Raiders gathered to drink a toast of cognac to their fellow airmen lost during the raid and those who passed away during the previous year. The last such reunion was held in November 2013 at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. At the time, four Raiders remained, Colonel Richard Cole, pilot of B-25 No. 1; Lt. Col. Robert L. Hite, co-pilot of B-25 No. 16; Lt. Col. Edward Saylor, flight engineer and gunner of B-25 No. 15; and Staff Sgt. David Thatcher, a gunner aboard B-25 No. 7.

For years, the surviving Doolittle Raiders gathered to drink a toast of cognac to their fellow airmen lost during the raid and those who passed away during the previous year. The last such reunion was held in November 2013 at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. At the time, four Raiders remained, Colonel Richard Cole, pilot of B-25 No. 1; Lt. Col. Robert L. Hite, co-pilot of B-25 No. 16; Lt. Col. Edward Saylor, flight engineer and gunner of B-25 No. 15; and Staff Sgt. David Thatcher, a gunner aboard B-25 No. 7.

Only Three Remaining

Now there are three. Saylor passed away in January at the age of 94 in Sumner, Washington. Like so many other young men, he was 19 when he enlisted in 1939 after seeing a recruiting poster that promised pay of $78 a month. Born in Brusett, Montana in 1920, he served 28 years in the Air Force and retired in 1967.

The news of Saylor’s death offers an opportunity to reflect on the courage and willingness to go in harm’s way that characterized to a man those intrepid Doolittle Raiders. In a 2013 interview Saylor told the Associated Press, “It was what you do. Over time, we’ve been told what effect our raid had on the war and the morale of the people.” He once observed, “There is no way you can call yourself a hero. That is for someone else to say.”

In 2014, the Doolittle Raiders received a gold medal from the U.S. Congress for “outstanding heroism, valor, skill, and service to the United States in conducting the bombings of Tokyo.”

Saylor was buried quietly next to Lorraine, his wife of 69 years, who passed away in 2011. In lieu of flowers, he requested donations to the Wounded Warrior Foundation. Throughout its history, the United States has been fortunate that heroes have stepped forward during wartime. Today, heroes continue to volunteer in defense of their country. Edward Saylor saluted them, and so should we.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments