By Arnold Blumberg

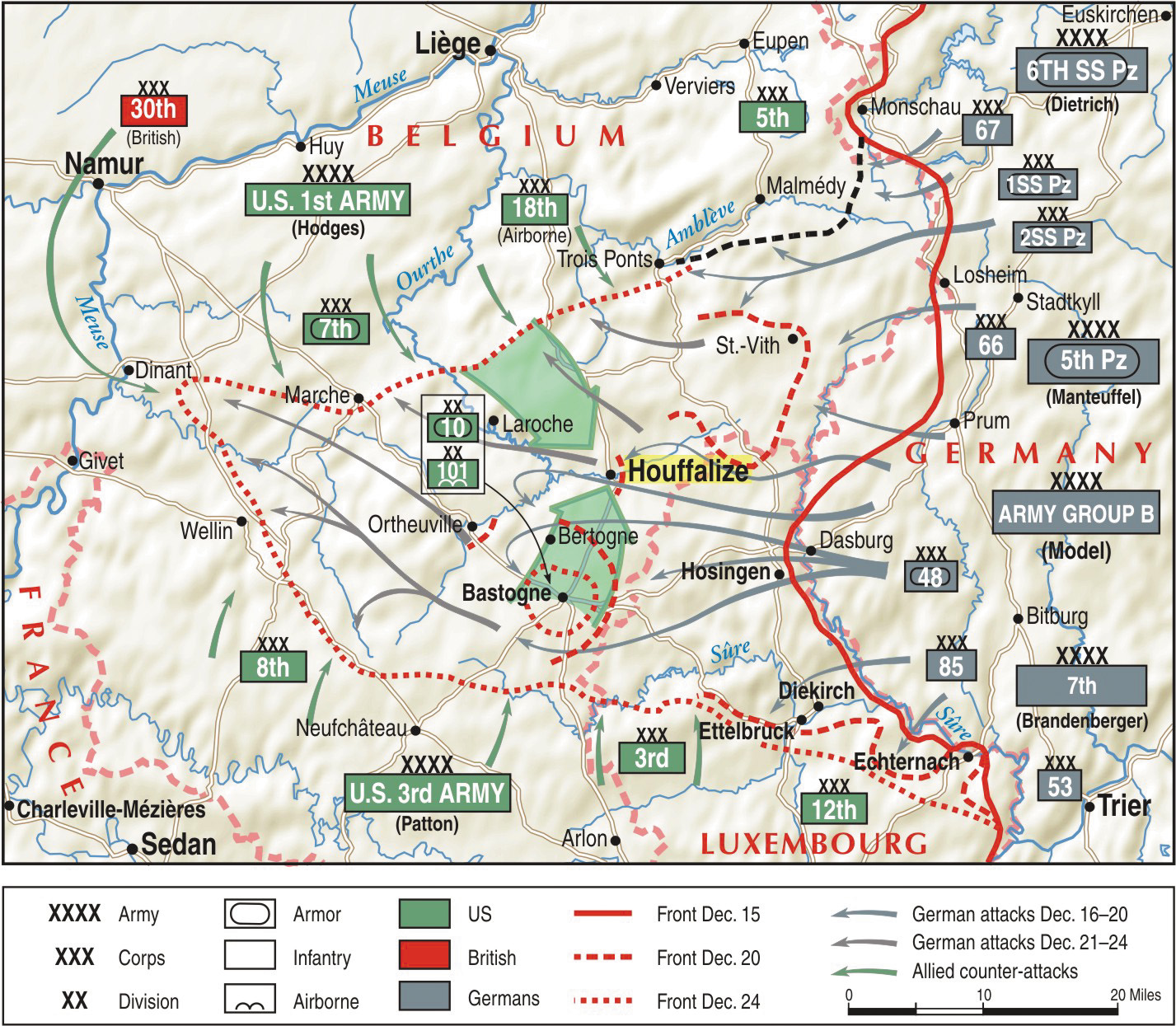

Wednesday, December 27, 1944, found the military situation in the Ardennes Forest of Belgium stalemated. After 12 days of unrelenting struggle, the American and German forces on this part of the Western Front found themselves locked in brutal combat, unable to drive each other back. The Americans were situated west beyond the Meuse River, the Germans along the West Wall to the east.

Both antagonists knew this situation would not last long. With the large volume of American infantry, tanks, artillery, and air power streaming into the theater of operations, supported by British forces to the north and west, it would be just a short time before the initiative slipped from the hands of the Wehrmacht into those of the Allies.

Realizing that a breakthrough across the Meuse River and then on to the principal Allied supply port of Antwerp was no longer possible, the German focus of the Battle of the Bulge dramatically changed. The German generals wanted to evacuate the 75-mile-long, 40-mile-wide salient, or Bulge, which the Wacht am Rhine (Watch on the Rhine) offensive of mid-December had driven into the American lines, but Hitler, as Supreme Commander, refused to allow the withdrawal. Instead, he ordered that all the available resources left to his army in the area be directed toward the elimination of the Americans defending the vital road junction of Bastogne.

Hitler Decreed the Town’s Complete Destruction

The Führer had been enraged that Bastogne had not only held out against his army’s onslaught, but had been relieved, even if tenuously, from encirclement on December 26. Concluding that the failure to capture Bastogne was the fundamental cause of the Germans inability to cross the Meuse, Hitler decreed on the 26th that the town must “be cleared,” a euphemism for its complete destruction along with any and all defending enemy troops.

As those responsible for carrying out Hitler’s will scrambled to organize this effort, the U.S. Army revised its plans for continuing the fight in the Ardennes. Before December 27, the Americans had to conduct a defensive war against an initially overwhelming attack by German forces. From that date onward, the U.S. field commanders determined to use their growing materiel strength in an offensive manner. Even before the 27th, men like General George S. Patton Jr., the flamboyant leader of the U.S. Third Army, and General Matthew B. Ridgway, in charge of the U.S. 17th Airborne Corps, urged their ground commander, General Omar Bradley, to begin immediate and simultaneous attacks on the northern and southern shoulders of the Bulge. The pleas of these experienced soldiers, however, went unheeded.

After the German siege of Bastogne had been broken, Patton again put forward his plan for the eliminating the Bulge. This time he placed the scheme in front of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe. It called for Patton’s army to drive north and northeast from Luxembourg City into the westward-protruding portion of the Eifel region of the Ardennes. There it would link up with a thrust by the U.S. First Army coming south from the area of Pruem, a road junction a little over 10 miles inside Germany, southeast of St. Vith. Patton’s approach was to cut off the enemy penetration at its easternmost base.

Although Patton’s counterpart in First Army, Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges, agreed with Patton in principle, he did have one serious reservation about the plan. He felt that the road network over which his army would have to conduct its advance was inadequate to sustain the heavy force of armor and transport needed for First Army to deliver an effective blow. In this objection, he was supported by Bradley, chief of the U.S 12th Army Group. Bradley doubted the suitability of Patton’s design for additional reasons. First, he felt that the terrible winter weather in the Ardennes would curtail both the movement of American ground forces and the necessary air support vital to any successful offensive operation. Second, lack of reserves to sustain the attack and the difficult terrain that would be encountered in the American drive greatly concerned him.

Patton’s Proposal

If the objections of his U.S. comrades were not enough to squelch Patton’s audacious plan to cut off the Bulge at its base and bag every German in it, the reservations of British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery definitely put a damper on the idea. Montgomery had been given command of all the Allied forces, including the U.S. First and Ninth Armies, north of the Bulge on December 20. This was deemed necessary because of the complete breakdown of communications between the First and Third Armies due to the German breakthrough.

Montgomery did not believe First Army would be able to launch a serious offensive for three months because of its losses during the Bulge fighting. He also cited the lack of any sizable reserves available to support an assault by First Army. The field marshal’s refusal to commit more British forces to the Bulge area in order to free up American divisions for an offensive made certain that a lack of reserves would dog the American effort to push back the Germans in the weeks to come.

As an alternative to Patton’s proposal, Montgomery, with backing from Bradley, got Eisenhower to consent to a plan to eliminate the Bulge by cutting it off at the waist, not the base. As presented, Third Army would strike northeast from Bastogne toward St. Vith while First Army moved southeast. The two armies would meet at the town of Houffalize, nine miles northeast of Bastogne. After the link-up, the Americans would attack east to St. Vith.

Assigned to carry the weight of the attack for Third Army was Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton’s VIII Corps, part of the First Army, but for command and control purposes serving under Third Army. Middleton’s troops were to jump off from their positions around Bastogne, move west of that town, then northeast to Houffalize. The corps, which comprised about 90,000 men, was made up of one combat command of the 10th Armored Division, the 11th Armored Division, the 17th and 101st Airborne Divisions, and the 87th Infantry Division.

First Army’s main effort would be made by its VII Corps under Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins. Heavily reinforced and approaching 100,000 men, VII Corps included the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions; the 83rd, 84th, and 75th Infantry Divisions; and 12 independent artillery battalions. Starting from the Hotton-Ourthe River area across the Bastogne-Liege highway, it was to advance southeast between the Ourthe and Lienne Rivers to take the high marshland of the Plateau des Tailles, which commanded the town of Houffalize 12 miles away.

The standoff in the Ardennes abruptly ended with a renewed German push against Bastogne. While the front remained quiet in the north, between January 2 and 4 repeated attacks were delivered by the Wehrmacht on the American-held bastion in the south. Under a hail of concentrated U.S. artillery fire in conjunction with American III Corps counterattacks, the Nazis were stopped cold. This proved to be the final German offensive effort in the Battle of the Bulge. Concluding that the enemy’s attacking power was spent, Montgomery ordered the First and Third Armies to commence their attack toward Houffalize on January 3.

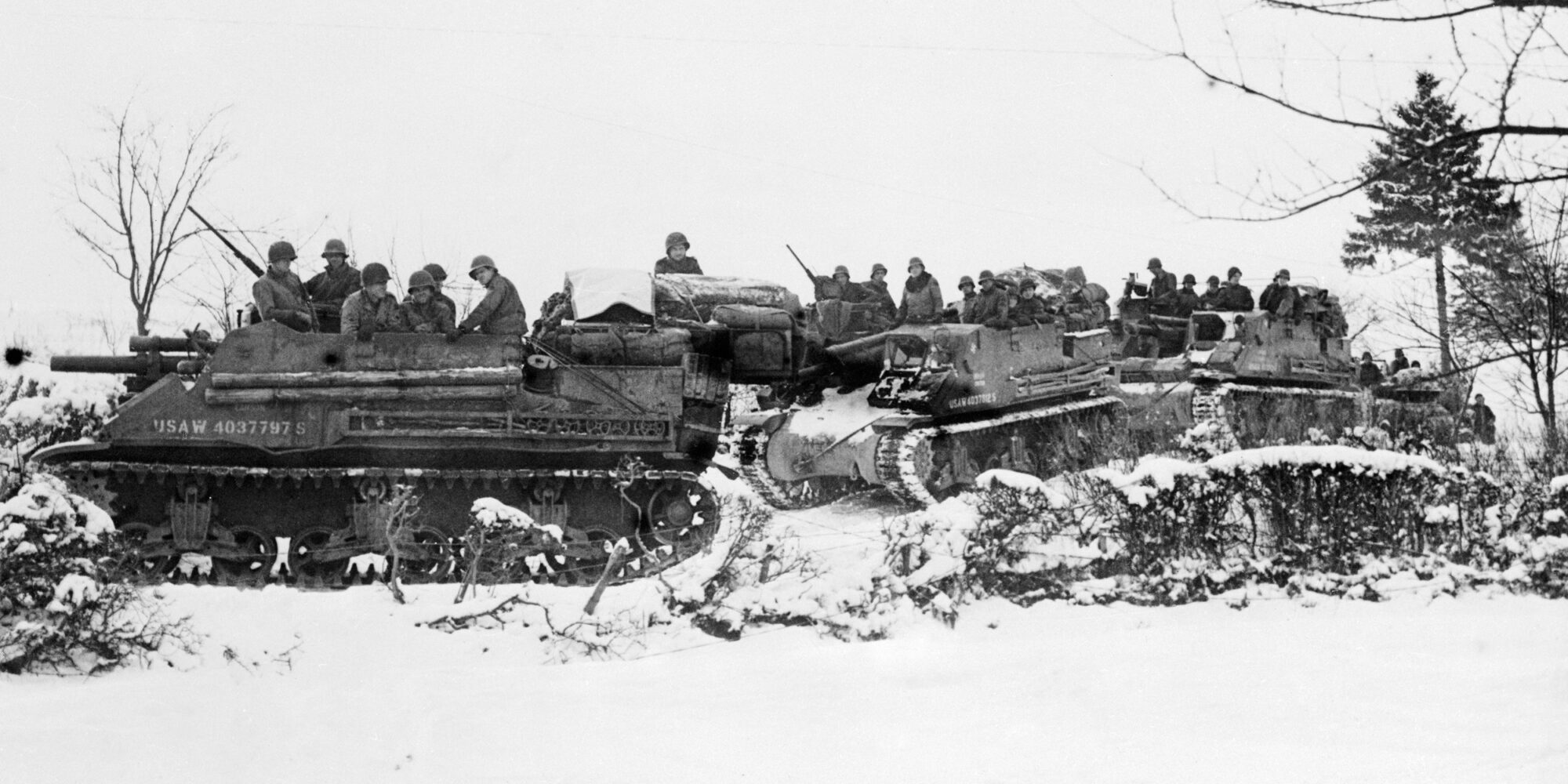

From January 3 through 14, the American northern and southern strike forces edged toward Houffalize. The going was tough. The Ardennes proved to be a natural military obstacle, easy to defend and murderous to attack. They not only had to face a determined and enterprising foe, but also freezing weather, severe icy conditions, snow to depths of up to two feet, dense pine forests, deeply cut ravines, steep cliff-like ridges, and swift streams.

Heavy Losses From the German Infantry & Panzer Formations

Compounding the extremely difficult geography was a general lack of roads in the region. Road movement was critical, especially in First Army’s area of operations. Only one major road, the Liege-Houffalize-Bastogne highway, led directly to the objective. A network of secondary roads and tracks intersecting with numerous villages, bridges, defiles, and hairpin curves would have to be navigated in the face of enemy opposition. The conditions were miserable for both armored and nonarmored vehicles, requiring that the infantry often take the lead and engage the enemy alone since the tanks and assault vehicles could not freely maneuver in the wilderness. Additionally, overcast conditions decreased visibility to the extent that close air support and artillery were never assured.

Facing the two American drives toward Houffalize was a mixture of German infantry and panzer formations. These were mere shells of their former selves after the ferocious fighting they had been through during the past weeks. Strengths in the infantry divisions varied from 1,500 to 2,500 men, and there were around 5,000 to 6,000 personnel in the panzer units. Losses had been so high and maintenance so difficult that a German armored division counted itself lucky to have 30 fighting vehicles operational at any given time.

The Waffen SS panzer divisions of Sixth Panzer Army, fronting the northern part of the Bulge, had either been shifted to the Bastogne sector by mid-January or pulled back behind St. Vith to guard against an attack near the base of the original German penetration. This left only understrength formations, including the 560th Volksgrenadier Infantry Division and the 116th Panzer Division to face the American onslaught from the north. Fearing an imminent collapse of that face of the salient and the potential entrapment of German troops at the most distant penetration of the Bulge, the commander of the Fifth Panzer Army, General Hasso von Manteuffel, requested an immediate pullback to a line anchored on Houffalize. His plea was not granted until January 8, and then only to the extent that the tip of the Bulge was evacuated.

The snail-like pace of the northern and southern thrusts to Houffalize continued through the 14th, hampered by snow-storms and clever German resistance centered on the use of minefields and ambushes abetted by counterattacks employing small groups of mixed infantry, armored, and antitank forces. On the 14th, Hitler was finally persuaded to allow a withdrawal of his army to the high ground just east of Houffalize, extending northward behind the Salm River and southward through existing positions east of Bastogne. On January 15, an advance guard of the 101st Airborne entered the village of Norville five miles south of Houffalize.

“When Houffalize is taken, we will have a junction between the First and Third Armies, which will put Bradley back in command of the First Army. This will be very advantageous, as Bradley is much less timid than Montgomery.” Thus wrote George Patton in his diary on the night of January 12, 1945. In the same entry, he noted that VII and VIII Corps should be in Houffalize by the next day, “as there is not much in the way.”

Major Michael Greene Asked to Lead the Operation

The Third Army chief was mistaken; January 13 came and went with the main concentration of VIII Corps seven miles from the town. Notified that elements of the First Army were just west of Houffalize on the banks of the Ourthe River, Patton determined to take it by pushing a flying column of Third Army troops north. The move would not only give his command credit for the amputation of the German bulge, but would also deprive Montgomery of the honor. To Patton, the feat would be a repeat of the race to Messina 17 months before. There, to Montgomery’s profound chagrin, the Americans under Patton beat the British to that city, signaling the end of the campaign for Sicily.

Patton gave the task of taking Houffalize to Brig. Gen. Charles S. Kilbrun’s 11th Armored Division and, via the fortunes of war, Major Michael J.L. Greene was tapped to lead the operation. Greene was a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy class of 1941. Before being assigned to the 11th Armored, he had served in the 2nd and 7th Armored Divisions, rising from platoon to squadron leader. After attending the Command and General Staff College in 1943, the 26-year-old was posted to the 41st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron of the 11th Armored Division as its executive officer.

On January 15, the 41st, commanded by Lt Col. H.M. Foy, was attached to the 11th Armored Division’s Combat Command A and deployed along the northern fringe of the Les Assins Woods near the village of Monaville, Belgium. At 11 am on the 15th, the squadron, made up of Troops A, C, D, and E supported by the 16 Stuart light tanks of Company F, was ordered to hand over responsibility for its sector to the 17th Airborne Division and move to Monaville and then north and east to Bertogne. The squadron protected the left flank of Combat Command A’s eastward advance along the line Pied Du Mont Woods-Comogne-Rastadt-Velleroux. When Greene reached Bertogne with most of the unit in tow during midafternoon, he discovered Colonel Foy had gone forward with Troop C, leaving Greene in command of the bulk of the squadron.

No sooner had Greene reached the town than the commanding officer of Combat Command A, Brig. Gen. W.A. Holbrook, Jr., accompanied by the division chief of staff, Colonel J.J.B. Williams, drove into the village looking for Colonel Foy. Greene reported that Foy was not in town.

General Holbrook looked at the major and said, “Okay. We have another mission that you and the remainder of the squadron must undertake. This is an extremely important mission, a must, directed by the army commander.” He went on to say, “We must get to Houffalize tonight and contact the First Army as it comes down from the north.”

Colonel Williams then spoke up and in a grave voice told Greene, “This is a difficult assignment for anyone because Houffalize is at least 10 miles behind German lines. But someone must get through to establish contact with the 2nd Armored Division as it comes down from Achouffe. They may be already there. General Patton wants this mission accomplished without delay, and he wants this division [11th Armored] to do it.”

Green’s Deliberating Mind Raced at a Mile a Minute

Holbrook broke in at this point with a wave of his hand and the comment, “Here is an excellent reconnaissance squadron mission. We’ve got to get around to the northern flank of the division and then through the German lines if they extend that far. It should be interesting.”

Greene showed no emotion as the other two officers spoke, but his mind was going a mile a minute. He knew that the approaches to Houffalize, except by way of the main highway, were indistinct snow-covered trails meandering through dark woods—woods that would become a lot darker as night neared. Putting such thoughts aside, Greene ordered the squadron operations officer to round up any tanks and assault guns available and put D Troop on alert to move out immediately.

The major then began to study maps of the area and plan the details of the operation. Not long afterward, Colonel Foy joined the group of officers pouring over the maps in the squadron command post. Foy formally put Greene in charge of the force heading into Houffalize.

Greene’s ad hoc strike force consisted of Troops D and E, the 2nd Platoon of Troop A, and the light tanks of Company F, the latter unit under Captain Harold Mullins. The last two units were on outpost duty beyond the town of Bertogne, so they were radioed to meet Troops D and E outside the village of Rastadt, two miles from Bertogne, as soon as possible. Riding in his half-track behind the last vehicle of the point, Greene led his small, lightly armed command, consisting of 17 M5 light tanks, 15 M8 Greyhound armored cars, six assault guns, 15 jeeps, and six M3 halftracks with 450 men, out of Bertogne at 5:30 pm.

As Greene’s group departed Bertogne, about 15 miles to the northwest, stood other American soldiers also determined to reach Houffalize. Like their comrades to the south, the men of the U.S. 2nd Armored Division had been plodding their way toward Houffalize since January 3. Forming the right wing of the VII Corps’ advance with the 84th Infantry Division in support, the unit had moved over a four-mile front for almost two weeks in atrocious winter weather, confined to roads that were treacherous due to ice and drifting snow.

Major General Ernest Harmon, commander of the 2nd Armored, summed it up nicely when he reported that the roads and trails his command had to travel on were “regular toboggan slides.” By January 9, Harmon’s troops neared the Ourthe River and were preparing to make the final lunge to Houffalize. On the 15th, division engineers bridged the river, and that evening an infantry patrol entered the village. They reported back that no enemy soldiers were seen. A concerted effort to take the town was made by Combat Command A the next day. While troops skirted the Ourthe River to the north, Sherman tanks charged in from the west. The tankers met small arms and antitank fire from panzergrenadiers of the 116th Panzer Division.

The Retreating U.S. Soldiers in the Village Were Disorganized, Unnerved, and Leaderless

Meanwhile, on the 15th, Greene’s column moved as fast as it could to the south on slippery roads toward its objective. Two miles outside of Rastadt, an enemy minefield disabled Greene’s halftrack. Fortunately, no one was injured in the explosion. After finding a detour around the minefield, Greene, now traveling in an armored car, entered Rastadt a little after 7 pm. There he met the platoon from Troop A and Captain Mullin’s light tank company. Happy to see his reinforcements, he was less pleased with other things he saw in the village.

Before Greene reached Rastadt, elements of Combat Command A had been driven back from the town of Velleroux by a German counterattack. Although the Germans had then retreated toward Houffalize, the Americans continued their own confused withdrawal through Rastadt. The retreating U.S. soldiers in the village were disorganized, unnerved, and leaderless, many simply milling about the streets as buildings burned around them.

However, Greene had his own problem: how to get to Houffalize in the growing darkness, over unfamiliar terrain and against an enemy whose location and strength he knew nothing about. A look at their maps showed Greene and his officers that they would have to take a single-lane dirt road, which was under at least a foot and a half of snow, from their present position north to Bonnerue, then continue over a trail intersected by a branch of the Ourthe River, which flowed through a deep valley west of Houffalzie. Daunting as the task was, Greene lost little time in getting his command on the road. He formed a main column with a reconnaissance detachment in the lead. The latter would act not only as a point formation, but also seek out alternative routes for the main force during the movement. Greene hoped to avoid any contact with the Germans until he reached Houffalize.

As his column cleared Rastadt at about 11 pm, January 15, Greene planned what he would do once he reached Houffalize. First, he would deploy his troops around the objective to contain any enemy found in the town. Second, the area of high ground south of the hamlet would be seized so cooperation with Combat Command A could be maintained. Third, patrols would be sent across the Ourthe River to make contact with the 2nd Armored Division.

Greene had hoped to bypass Bonnerue by moving cross-country to the south and east, but the rugged terrain and the deep snow forced the GIs to pass through the village. Moving by bounds, one unit going through the town while others covered the move, the squadron rattled through Bonnerue without incident. Unknown to Greene and his men, remnants of a German infantry company were hiding in the town as he came through. These Germans were captured on the 16th by another platoon of Troop A coming through Bonnerue.

Upon reaching the high ground northeast of Bonnerue, the American column’s progress was slow and tedious as it made its way in the dark through a thick forest and deep snow. The night was so dark and the snow so deep that one of Greene’s officers, Lieutenant Gene Ellenson, had to walk the entire distance to keep the column on the right route. Greene recalled later that they ”proceeded slowly, nervously and anxiously through the long dark night hoping that the next minute would bring daylight and the objective.”

Troop A Fell Victim to a Well-Concealed Tank Trap

At 3 am, they reached the Rau de Suhet stream about two miles west of Houffalize. The bridge over the watercourse was intact. The men began to cross, congratulating themselves that they would not have to get their feet wet to reach the opposite bank. Not far from the bridge they discovered that the trail leading from the stream traversed a moderately high slope and was ice coated. Wheeled vehicles could not ascend the hill.

So, for the next two and a half hours the tanks had to drag all the other motor vehicles up the hill. By 5:30 am on January 16, the height had been crested and the squadron placed in column of march to move along the track that led out of the Bois du Couturie and descended into the Ourthe River Valley. As the Americans rounded an unfinished water mill, their goal, Houffalize, came into view 600 yards to the east.

Greene prepared to make a dash for the town, but before he could issue the order, the lead armored car of 2nd Platoon, Troop A fell victim to a well concealed tank trap dug in the middle of the road just 200 yards from Houffalize. The trapped armored car blocked the road and stopped every vehicle behind it from going forward.

Frustrated by the mishap, but determined to get into town, Greene and Ellenson got out of their command vehicles and walked the distance to the town limits. Having done so, the two officers started to return to the stalled column. To their left and on top of a nearby rise, Ellenson spotted two figures in a foxhole. His repeated shouts at them to get their attention were without effect, and the two U.S. officers, thinking they were from a 2nd Armored Division patrol, decided to ascend the ridge and speak with the supposed friendlies. As they climbed the hill, Greene yelled to his armored car commander, Sergeant Till, that he and Ellenson were going up the hill and would return shortly.

When Greene and Ellenson were about 50 yards from the strangers in the foxhole, they saw one of the occupants rise and aim a machine gun at them while shouting “Hande Hoch,” German for “Hands up!” The two Americans halted. Ellenson raised his hands, turned to Greene, and said, “I guess we are caught, Major.” Greene hesitated for a second, then yelled to Till to start shooting at the Germans. As Till fired his machine gun at the enemy soldiers, the two American officers took the opportunity to slide down the hill and hot-foot it toward the column of waiting vehicles. The Germans did not fire at the fleeing Americans, but turned and ran back to the town.

Sergeant Till’s burst of fire seemed to set off a barrage of machine-gun, antitank, and mortar rounds directed at the immobile troopers from rear-guard elements of the 116th Panzer Division at Houfallize. Greene immediately ordered his men and vehicles to disperse and seek cover.

Missiles Rained Down on D Troop

Greene still had the mission of making contact with First Army in Houffalize. This required that he stay near his current position. To do this in the face of active enemy resistance, he decided to contain the Germans in the town with two of his six 75mm self-propelled assault guns from a position near the mill. In addition, he ordered Troop D to dismount and occupy the high ground south of town and act as forward observers for the assault guns, which began to bombard the town with indirect fire. Lastly, he moved the light tank company closer to Houffalize and the Ourthe River so the tanks could fire at any enemy holed up in Houffalize.

About this time, Greene received a radio message that Combat Command A was going to continue its push for Houffalize at 8 am. Although he tried, he could get no information on the whereabouts of the 2nd Armored Division. Soon after his dispositions were completed, German mortar fire was directed at the American assault-gun location, and several crew members were wounded. The guns were moved back. Artillery fire also fell on D Troop. Under the shelling, the troop relocated a little, but still managed to keep the town under observation from the north, south, and east. The situation was not made any easier when it was confirmed that the missiles raining down on D Troop came from First Army guns.

Around 9 am, D Troop’s commander, Lieutenant Ellenson, reported that he saw dismounted men 1,500 yards away, moving southeast on rising ground on the north shore of the Ourthe River. Feeling confident they were from First Army, Greene dispatched a patrol to meet the men Ellenson had seen.

After sending the detachment to the north, Greene ordered the tank company to break into Houffalize. He realized that tanks alone could not secure the place, but wanted them to merely dash in, size up any remaining enemy opposition, dash out again, and join D Troop south of town. The Stuart light tanks rushed over the open ground and road where the armored car had been caught in the tank trap, receiving only small arms and mortar fire as they advanced. The Stuarts then moved into the town, firing their 37mm cannon and .50-caliber machine guns, setting fire to buildings, and flushing out Germans in the process, and then withdrew to join D Troop.

The waves of men Ellenson had seen north of the Ourthe River early on January 16 were in fact members of the 2nd Armored Division, specifically part of Lt. Col. Hugh O’ Farrell’s Task Force A, Combat Command A. During the morning, part of O’Farrell’s command, Company F, 41st Armored Infantry, was having its picture taken by Sergeant Douglas Wood, a cameraman from the 165th Signal Photo Company. As Wood began filming the infantrymen lounging in their foxholes, a figure appeared out of the woods. He was waved in by the 2nd Armored men and soon followed by others. The newcomers, the patrol sent by Greene, had waded across the cold Ourthe River.

During their trek, Greene’s men had been joined by Colonel Foy. The colonel asked to be taken to a senior officer in charge, so Wood brought him to Colonel O’Farrell. The men recognized each other immediately, having been classmates at the Armor School at Fort Knox, Ky. It was 9:05 am, and the juncture between the American First and Third Armies had become a fact. The Bulge had been erased at last.

Around 10 am, Greene’s patrol reported back to the major on their meeting with elements of the First Army. Greene also heard of a link-up between his 3rd Platoon, A Troop and a 33-man patrol from the 334th Infantry Regiment, 84th Infantry Division, at the village of Engreux about 1,000 yards southwest of the Ourthe River at 9:45 am. The union of the two American armies had been cemented along the entire length of the Ourthe.

Terminating the German Offensive

Houffalize was secured by Combat Command A in the late hours of January 16. The little town, a prewar resort with a population of 1,200, stands in the loop of the Ourthe River. Correspondent Harold Denny wrote that Houffalize appeared to be a “miniature St. Lo,” due to the extensive damage inflicted upon it by American air bombardment while it had been held by the Germans. The town, which traced its roots back to medieval times, was a major supply depot for the German Army during the Battle of the Bulge and also served as headquarters for the 116th Panzer Division in the struggle’s final stages.

Just before Houffalize fell to the Americans, most of its inhabitants had fled and were living in the nearby woods. U.S. air and artillery attacks had not spared a single building. Civilian survivors told the Americans that over 200 of their number had been killed and more than 300 wounded during the week before the town was occupied by American forces.

Major Greene and his combat team did not get the opportunity to enter the object of their strenuous two-day mission. The 41st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron was withdrawn to Bonnerue at 4:30 pm on the 16th, leaving an outpost to the west of Houffalize.. An hour before they started their move back, the last of the 116th Panzer Division troops retired from the town.

Final resistance from the Germans was a running battle with a Tiger tank positioned on the main road leading into the town from the north. A Mark IV tank, situated in the town’s center near a roofless gray stone church, offered some parting shots before clanking its way east.

According to General Patton, the fall of Houffalize “terminates the German offensive. Now we will drive them back.” What he did not confide in his diary was that the elimination of the Bulge failed to do what most needed to be done; cutting off the German retreat eastward. Estimates assert that only about 20,000 Germans were captured when the Bulge was eliminated.

Patton had argued that to remove a monkey hanging from a tree by its tail, the proper methodology would be cutting off the tail, not punching the monkey in the face. The pincer movement on Houffalize was a “punch in the face,” which predictably failed to eject the monkey from the tree.

My father, Andrew P. Smith, was a Lt. in the 41st Armored Infantry Regiment, part of the Second Armored Division, attacking southward toward Houfalize. He described the fighting in The Bulge as “grim”. He was wounded by shrapnel on Jan. 6, 1945 and evacuated eventually to hospital in Scotland where he remained until the end of the war in Europe. He was discharged from the Army in August of 1945.

Excellent article. Suggest the author research the homonyms “poring” and “pouring” in regard to map reading.

Good article, with plenty of detail on the G.I.’s movements throughout the area. I used Google Earth to find a lot of the villages, and saw just how close they were to each other in proximity. The up and down wooded terrain and the terrible winter weather conditions no doubt added to the hard going both sides experienced in the battle. When I was active in WW2 reenacting years ago (doing a 28th Infantry Division portrayal and, yes, doing Battle of the Bulge scenarios), we had in our unit a WW2 vet who served in a 105mm artillery unit while in the 83rd Infantry Division. He remembered hearing about the Malmedy Massacre and how it affected the G.I.s’ outlook upon German prisoners. Not good at all.