By Louis Ciotola

In the early 15th century, the strongest military powers in the world resided in Asia. Arguably, no two were more powerful than the Ottoman Empire of Bayezid I and the Tartar Empire of Tamerlane (Timur the Lame). During their lifetimes, both men carved out extensive realms of influence in western Asia and southern Europe. But there was a limit to their expansion, and in the rocky terrain of eastern Anatolia the two great empires converged. It was there, on July 20, 1402, that Bayezid and Tamerlane fought a climactic battle for dominance over the Muslim world and beyond.

The younger of the two rivals and the better known to the western world was Bayezid I, fourth sultan of the burgeoning Ottoman Empire. Nicknamed “the Thunderbolt” because of the speed and frequency with which he moved his armies across the land, Bayezid inherited territories in southern Europe and the westernmost portion of Asia, a region known as Anatolia. Initially, the new sultan concentrated on expanding his European realm, which his father Murad I had conquered before him, but when this proved a failure, the sultan turned to a more pressing matter—Constantinople.

Sitting on the strait between Europe and Asia, Constantinople was the capital and nearly the last remaining bastion of the dying Byzantine Empire. In 1394, the Ottoman Turks attempted to capture it, beginning a siege that was to last for the next eight years. Two years into the effort, Bayezid was rudely interrupted by a European army of crusaders

summoned by pleas from the Byzantine emperor. In the ensuing Battle of Nicopolis, the Turks, assisted by their Serbian allies, decimated the cream of European chivalry. That triumph against the infidels propelled Bayezid to folk-hero status within the Muslim world and allowed him to continue the process of empire building undisturbed.

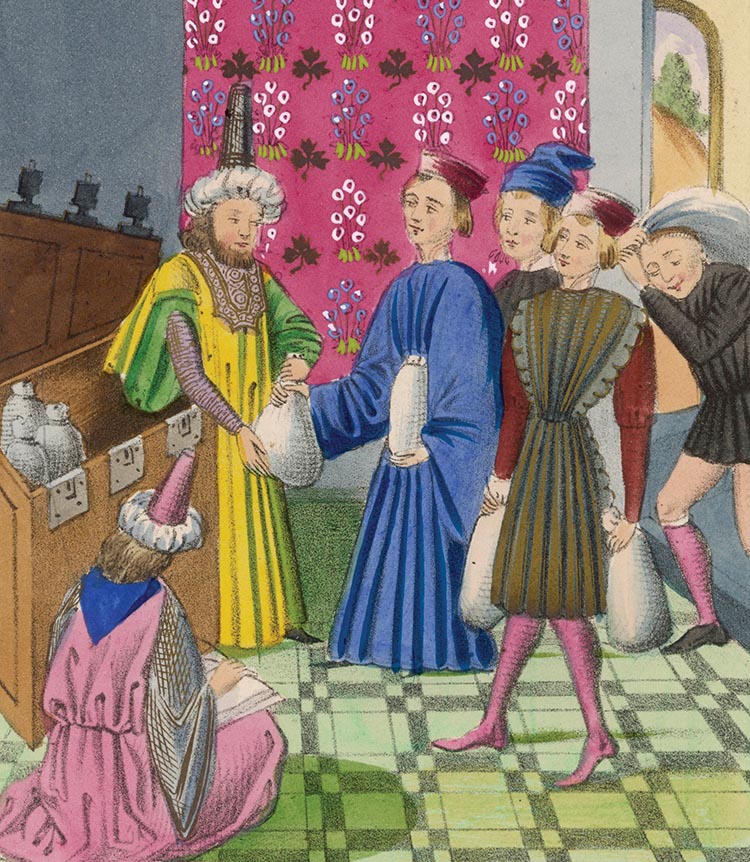

Tamerlane ‘the Lame’

Meanwhile, seemingly a world away to the east, another warlord was creating his own empire. Not only was this conqueror more experienced than Bayezid in the ways of war, he was also far more terrifying personally. Claiming moral supremacy in the Muslim world and, conversely, a direct lineage to the great Mongol ruler Genghis Khan, Timur, more commonly known in the West as Tamerlane, had been carving a bloody trail across western and southern Asia for the better part of three decades. His rise to power began among the numerous Tartar tribes of Central Asia, and despite injuries to his right leg, arm, and hand that forever left him branded “the Lame,” Tamerlane’s rise never relented. From his capital of Samarkand, Tamerlane’s Tartar armies butchered their way through the Asian steppes, Persia, the Caucasus, and Russia with ruthless efficiency.

Tamerlane’s calling card, the construction of grisly pyramids of human skulls, left no one in doubt of his ferocity. In 1398, he completed his most dazzling triumph yet, a victory in India over the Sultanate of Delhi. Following this, he immediately headed west to deal with rebellious Armenian vassals. It was then that his empire and the empire of Bayezid the Thunderbolt, once so far away from each other, at last came into close proximity. Confrontation was all but inevitable.

Initially, the desire for territory was not the cause of tensions between the two rulers. Rather, it was the refusal of either to recognize the other’s supremacy. Such recognition could only come from bowing to certain demands, an idea both rulers found completely abhorrent. Vassal states caught between the Ottomans and Tartars, as well as defeated rulers taking refuge within the rival empires, became flash points of contention. By the spring of 1400, both of these issues were at the forefront of Bayezid’s and Tamerlane’s increasingly strained relations.

The primary refugee in question was Prince Tahir, son of Sultan Ahmed of Baghdad. Prince Tahir, an insurgent who had assisted the Armenians in their latest rebellion, had escaped his Tartar pursuers and fled to sanctuary inside the Ottoman borders. Tamerlane demanded his return and, being the haughty ruler that he was, did so in an insulting manner. In his first letter to Bayezid, Tamerlane wrote: “Be contented with that which Allah has given you and with what you have seized from the unbelievers but give up immediately those provinces which you have stolen from other rulers so that Allah will be gracious to you. If not then I will be the avenger with Allah’s assistance.”

The Ottoman sultan, who was already upset because Tamerlane had granted protection to the princes of Rum who once controlled lands claimed and conquered by the Turks, was taken aback by the Tartar emperor’s audacity. No one could address the sultan in such a way. That Bayezid did not think highly of Tamerlane was clear. The Spanish envoy Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo even claimed that the sultan had never heard of the Tartar warlord, although that was unlikely. Unsurprisingly, in reaction to Tamerlane’s letter, Bayezid responded with his own insult, ordering the beards of the Tartar envoys to be shaved and the emissaries returned to their master in disgrace to demonstrate that the Ottoman sultan feared no man. The war of words was on.

Matters were further complicated by Taharten of Erzinjan, a prince in eastern Anatolia who had willingly become a vassal of Tamerlane as a safeguard against the Turks. Taharten’s tiny state was blocking Ottoman expansion, and Bayezid demanded that he accept Ottoman authority. Already angered that Taharten had spurned him for Tamerlane, Bayezid was further upset that Tamerlane was advising his new vassal about how to resist a possible Turkish invasion. Meanwhile, Tamerlane was beginning to suspect that the Ottomans were planning a coalition against him with the Mamluks of Egypt. With this in mind, he wrote again to the sultan. “Since the ship of your unfathomable ambition has been shipwrecked in the abyss of self-love,” he warned, “it would be wise for you to lower the sails of your rashness and cast the anchor of repentance in the port of sincerity, which is also the port of safety; lest, by the tempest of our vengeance you should perish in the sea of punishment which you deserve.”

Tamerlane tempered his threats by suggesting that he was willing to leave the Turks in peace due to their valiant campaigns against the Christian infidels. Bayezid was far from appeased. He thundered back: “We will come and seek you out and pursue you as far as Tabriz and Sultaniya. Then we shall see in whose favor heaven will declare and which of us will be raised to victory and which abased by a shameful defeat.” Believing more and more that a war was imminent, Tamerlane began taking steps to undermine his rival’s standing in the Muslim world.

Provoking the Tartar

The cold war turned hot in mid-1400 when Bayezid, busy conducting the siege of Constantinople, dispatched his eldest son Suleiman with a small army to eastern Anatolia to contend with Taharten’s ongoing obstinacy. Charged with the task of coercing the prince through force, Suleiman’s invasion drove Taharten out of Sivas, which the Turks then established as a base from which to attack Armenia. Tamerlane reacted swiftly to the challenge. In August, he assembled his army and marched it directly on Sivas. Vastly outnumbered, Suleiman prudently withdrew after only a few minor skirmishes, leaving Sivas and its garrison to fend for itself. The city held out for 18 days against a brutal siege before falling. Tamerlane immediately ordered the garrison butchered. To the chief Ottoman defenders, however, he promised that their noble blood would not be spilled. Instead, the merciless Tartar buried them all alive.

With the capture of Sivas, the rest of Anatolia lay virtually open to invasion by the Tartar horde. Tamerlane wasted little time in attempting to take advantage of his leverage, hoping a display of his military might would be enough to persuade Bayezid to adopt a more conciliatory attitude. He repeated his previous demands and now increased them by insisting on the obeisance of the sultan’s many sons. An incensed Bayezid naturally refused. But Bayezid was unable to attack Tamerlane immediately; it would take a substantial amount of time to break off the siege of Constantinople, reorganize his army, and march eastward. For his part, Tamerlane was in no hurry to come to blows. Instead, without fear of an impending Ottoman offensive, he was free to turn on the Egyptian Mamluks and eradicate any possibility of a future coalition against him. Over the course of the next year, Tamerlane sacked Damascus, subdued Egypt, and crushed a rebellion in Baghdad. It was only then that he turned his eyes on the Ottoman juggernaut.

While Tamerlane was away in Baghdad, the next act in the drama unfolded. Once again, Bayezid sent his son Suleiman to chastise Taharten. This time, however, Suleiman’s campaign was a disaster. The setback forced the sultan to initiate negotiations with Tamerlane, if only to play for time. With Taharten acting ironically as mediator, the correspondence between the two powerful rulers resumed. As before, Tamerlane offered stiff terms. Since the previous year, the number of refugees hiding inside the Ottoman Empire had grown. Most notorious was a rebellious Turkmen chief named Kara Yusuf. Tamerlane demanded that Yusuf be either turned over or executed, writing, “There is nothing more disagreeable to us than to hear that he [Bayezid] grants protection to Kara Yusuf Turcoman, the greatest robber and villain on earth.” This time, the Tartar threatened war if the sultan failed to carry out his demands. Publicly, Bayezid scoffed, but he soon lifted the siege of Constantinople and began mobilizing his massive army for an eastern campaign.

Tamerlane also began preparing for a conflict that was growing more imminent with every angry letter exchanged. Late in 1401, he started pressuring the local Christian states for assistance. Many were more than happy to provide aid against the Turkish foes they had been battling for decades. The regent John of Constantinople eagerly pledged his support to the Tartar emperor, promising men, galleys, and gold. Manuel III of Trebizond, on the other hand, was less enthusiastic about helping the Tartars. Residing farther east, he recognized more clearly the danger the Tartars represented. When Tamerlane threatened Trebizond with devastation, Manuel hastily pledged his support to Tamerlane in the coming war.

“The Son of Othman is Mad”

By the spring of 1402, Tamerlane was running short on patience. In a letter to Bayezid that April, he demanded that the Turkish fortress of Kamakh be turned over to him. Before he received the expected negative response, he ordered his favorite grandson and heir, Mohammed Sultan, to take Kamakh by force. The act was nothing short of a declaration of war, and Mohammed captured the fortress in just 11 days. Following this, Tamerlane marched to Sivas with the bulk of his army, where he was greeted by Ottoman envoys bearing more insults from the sultan.

Bayezid, sitting with his army outside his capital of Bursa, was determined to avenge Kamakh personally. He planned for a rapid advance and a decisive battle, one that would not only punish Tamerlane but also strike fear into the hearts of the impudent Christians. His newest letter branded Tamerlane “a brigand, a shedder of blood, who violated all that is sacred, broke pacts and obligations, with an eye turned from good to evil.” It went on to goad Tamerlane into invading, jeering, “If you should not come, may your wives be condemned to triple divorce.” Shocked at the mere reference to women, Tamerlane could only reply, “The son of Othman is mad.” This was the abrupt end of the correspondence between the sultan and the emperor. It was time for them to back up their war of words with action.

Tamerlane made one last demonstration before the coming of all-out war, parading his army before the Ottoman envoys, but the emissaries were unimpressed. The emperor sent spies to follow the ambassadors back to Bayezid’s camp, tasking them with coaxing the sultan’s Tartars into trading allegiances by playing on their ethnic identity. This would be no easy task, according to the Syrian chronicler Ahmed Ibn Arabshah, since the Tartars had joined the Turks willingly. Nor did Tamerlane’s generals think the war would be easy. They persuaded an influential emir to convey their doubts to the emperor, but neither the argument that their men were exhausted nor their warnings about the sophistication of the Ottoman army could change Tamerlane’s mind. The Ottoman sultan had challenged the mighty conqueror’s pride. Now the sultan must pay.

The Bayezid Advances. Tamerlane Evades

Bayezid moved first. With Tamerlane’s men already uncomfortably close to the eastern border of his empire, the sultan and his army left the safety of Bursa for Ankara. There he set up camp, intending to prevent the enemy from advancing into Ottoman Anatolia, a grim prospect that would surely lead to the destruction of his most fertile territories at the hands of the marauding Tartars. Meanwhile, Tamerlane remained at Sivas, waiting for the first opportunity to strike.

The Turks stayed only briefly outside of Ankara. Bayezid was still determined to have his decisive battle and so continued his march, heading for Tuqat, 65 miles northwest of Sivas. There he hoped to lure Tamerlane into attacking. The spot was ideal for defense. The entire area was covered by thick forests, which would largely neutralize Tamerlane’s predominantly mounted army. The Tartars, however, were far more cunning than the crusaders, and Tamerlane was much too experienced to fall for Bayezid’s obvious ploy. He easily recognized the disadvantages he would face at Tuqat and immediately devised a new strategy to exploit the situation.

Since his army was mostly cavalry, Tamerlane knew that he had the ability to easily outmaneuver the more cumbersome Turkish force. He decided to march south, directly into Bayezid’s undefended lands. There would be no way the sultan could catch him or cut him off. Racing along the outside of the Halys River, the Tartars dashed into central Anatolia. With the river shielding their advance, Tamerlane’s horsemen seemed to vanish into thin air. Initially, Bayezid foolishly believed that Tamerlane’s march was a withdrawal and an indication of weakness, but he soon understood the tactics of steppe warfare as the enemy ravaged his harvest and raided his villages.

Bayezid became nervous and frustrated as he desperately searched for the Tartar invaders. His army was already starting to suffer as it traversed fields laid waste by Tamerlane’s merciless horsemen. For his part, Tamerlane was full of confidence, observing with satisfaction, “Their army is mostly infantry, and marching will tire them.” The Tartars gained so much ground that they even felt safe to rest along their march, which now was directed at Ankara. Following a 12-day trek and a minor skirmish at Qir Shahr, the Tartar army reached its destination.

Besieging Ankara

Tamerlane’s arrival at the former Turkish camp was a shock to Bayezid. When the sultan heard the news, witnesses said, he was “seized with panic as though it were the day of resurrection.” Tamerlane had made his rival appear to be an amateur at the art of war, and with his enemy still days away, he was free to choose his ground and besiege Ankara. He chose a spot northeast of the city and immediately ordered the construction of trenches and fortifications. The Tartars also diverted the course of a small river flowing into Ankara in order to deprive the city of fresh water. When the Turkish army arrived three days later, early on the morning of Friday, July 28, Bayezid had already lost some 5,000 men due to the wretched conditions of the land. He now found to his dismay that he also lacked water to quench his army’s thirst. Given both the perilous situation in Ankara and the unbearable summer heat, Bayezid had no choice but to offer battle immediately.

The opposing armies were still assembling for battle as dawn broke on the morning of the 28th. The coming contest promised to be a massive affair. Each army totaled as many as 200,000 men, numbers that dwarfed the western standards of the day and created a battlefront of more than 15 miles. The Tartar army, led by its 66-year-old emperor, began the day by emerging from its fortifications in preparation for an offensive battle that would best utilize its massive cavalry forces. Tamerlane’s son, Prince Shahrukh, commanded the left with the assistance of one of the emperor’s grandsons, Khalil Sultan, while another grandson, Sultan Husayn, led that wing’s advance guard. The setup was identical on the right, where another son, Prince Miranshah, and a grandson, Abubakr, led the advance.

In the center, Tamerlane’s beloved heir Sultan Mohammed took command of troops fresh from Samarkand. Behind him with the reserves was the emperor himself. Light cavalry dominated the front ranks, poised to strike the enemy with speed and precision. There were even 30 war elephants captured from Delhi four years earlier. The Tartar standard was crimson, bearing a horsetail and a golden crescent. Those fighting beneath that standard were perhaps the most experienced soldiers in the world, many having fought with little pause for years across the huge expanses of Asia. According to Arabshah, when Tamerlane’s army moved, “wild beasts scattered, stars dispersed, tombs overturned, and the earth shook.”

The Ottoman Order of Battle

Bayezid’s army drew up north of the Tartars on the plain of Chibukabad. Despite their recent hardships, the Turks were far from demoralized, as some chroniclers would claim. Furthermore, assertions that the 48-year-old sultan had become lazy in his campaigning were entirely false. Still, given the situation, the Ottoman soldiers had virtually no time to rest between the end of their march and the beginning of battle. The Turkish left was a mixed force of professional cavalry, or Sipahis, and irregulars from Anatolia. The core of the wing was a force of 20,000 Serbian horsemen, fully armored under the summer heat and commanded by Stephen Lazarovic, Bayezid’s brother-in-law.

Already menacing in their armor, the Serbs also carried with them deadly Greek fire. Bayezid led the center, which included his 5,000-strong professional infantry corps known as the Janissaries. The Janissaries fortified themselves upon a hill in the middle of the plain screened by Sipahis. The sultan’s sons Musa, Isa, and Mustafa joined him in the center, while another son, Mehmed, led the reserves. The most critical part of the Turkish army was its right, commanded by Suleiman, where the sheer number of Bayezid’s ethnic Tartars was larger than Tamerlane’s entire force.

The Battle Begins

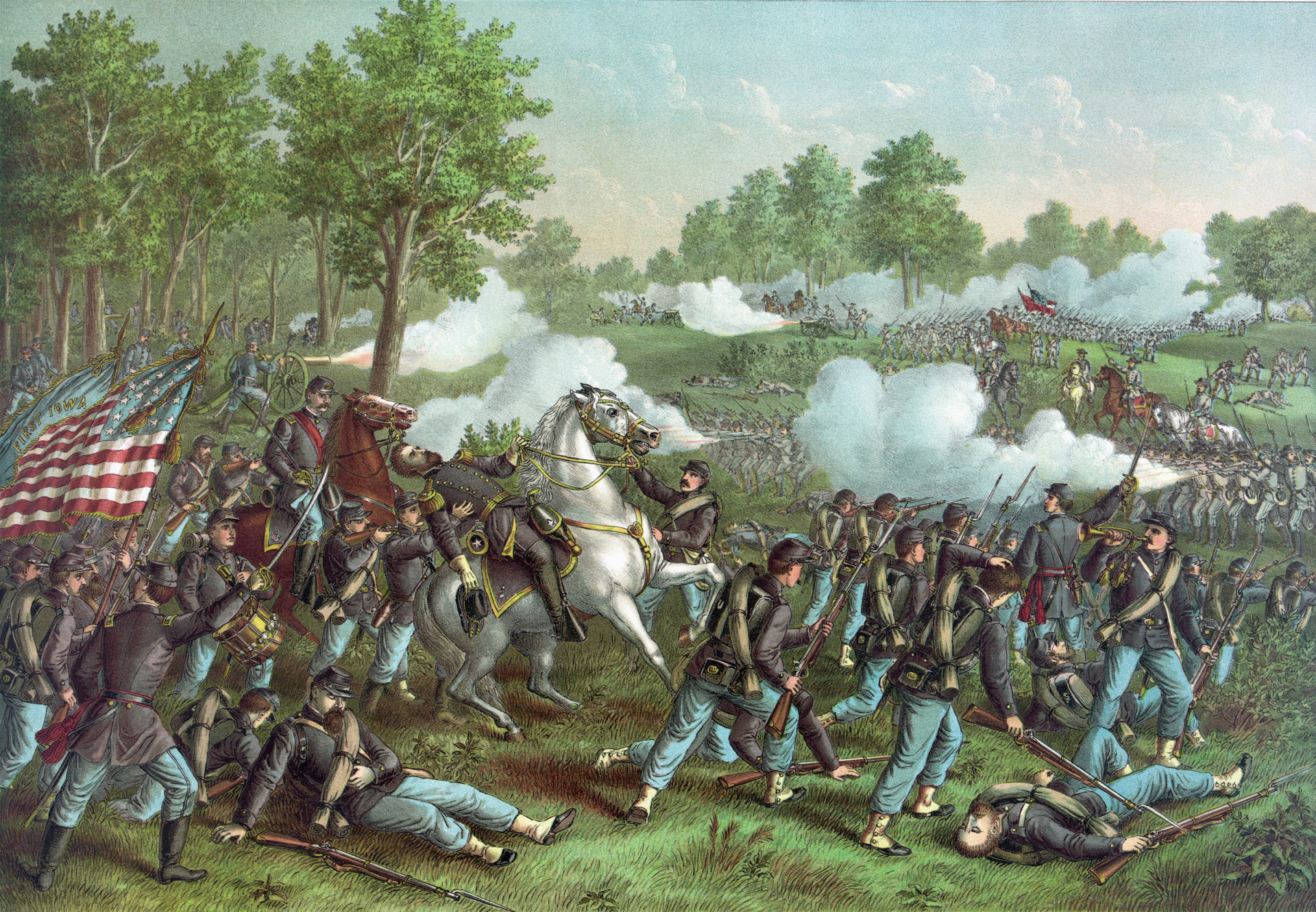

After both sides offered prayers to Allah in the hope of winning his grace for victory against an enemy of the common faith, the battle began abruptly at 10 am when the Tartar light cavalry advanced on the Serbs on the Ottoman right. Tamerlane hoped to drive a wedge between the Serbs and the Janissaries, but any illusion concerning Serbian weakness that he may have harbored was quickly dashed. The heavily armed Christians easily repelled the assault and mounted a counterattack of their own. With drums beating and trumpets blasting, Lazarovic’s horsemen slammed into the Turkish left flank.

The forces of Prince Shahrukh slowly gave ground, letting loose enough arrows to turn the sky black. The withdrawing Tartars also used Greek fire, but it was all to no avail. The Serbians advanced implacably. Even Tamerlane was impressed, declaring, “The wretches fight like lions!” Bayezid was uneasy, however, worrying that the Serbs had charged too far and risked being encircled. He carelessly surrendered the momentum and ordered Lazarovic to fall back.

The Janissaries Hold Firm

This was to prove the height of Ottoman success. On the opposite side of the battlefield, unmitigated disaster soon struck. There, the Tartar advance guard under Abubakr, preceded by a hail of arrows, charged headlong into Suleiman’s ranks. The fighting provided the spark that prompted Bayezid’s Tartars to cast aside their allegiance and rejoin their own kind in the struggle. Immediately the Tartars turned on the Turks, striking Suleiman’s Anatolians and Macedonians from behind.

Suleiman attempted to stand, but the tide had turned inexorably against him and he was compelled to avoid certain destruction by leading an orderly withdrawal. Bayezid’s fortunes were beginning to deteriorate. When the Serbs saw what was occurring on the opposite side of the field, they too lost heart and began to retreat, pursued closely by Husayn. As he pulled away, Lazarovic urged the sultan to abandon the fight while there was still time to save the army. Bayezid refused. An Ottoman sultan and the fiercely loyal Janissaries could never surrender with honor.

With only the vastly depleted Turkish center remaining on the field, the battle was all but decided. Eager for glory, Mohammed Sultan approached Tamerlane and requested the honor of delivering the final, fatal charge. Reluctantly the emperor consented, and within moments the ground shook as waves of mounted Tartar warriors stormed forward furiously. With suicidal determination, the Janissaries stood their ground, waiting for the charging horsemen to crash into them. The fighting was ferocious. The Janissaries defended their hill tenaciously, repelling numerous assaults including an attack by the war elephants whose backs bore tiny castles from which the Tartars rained down Greek fire on the Turks.

The Capture of Bayezid

No one could escape the carnage. Bayezid swung an ax to cut down his enemies. The slaughter continued until nightfall. Finally, with 300 men by his side, the sultan attempted to flee, but a Tartar arrow struck his mount and sent him tumbling to the ground. Tartar soldiers quickly pounced, capturing the illustrious ruler. According to legend, when a bound Bayezid was delivered to Tamerlane during the final moments of the battle, the emperor, who was peacefully engaged in a game of chess, said modestly to his captive, “I smile that God should have given the dominion of the world to a blind man like you and a lame man like me.”

Although an accurate estimate of casualties was impossible, one Dominican friar claimed later that at least 40,000 Turks had been killed. The rest fled with Suleiman to Bursa or with Lazarovic to Serbia. Along with Bayezid, his sons Musa and Mustafa also fell into Tartar hands, while Tamerlane’s favorite, Mohammed Sultan, was wounded during the battle’s bloody final phase.

The Ottoman Empire’s Fate

Following the crushing defeat of the Turkish army, the Tartars easily captured and desolated Ankara. At the same time, Mohammed Sultan, despite his injuries, raced after Suleiman, but Bayezid’s son moved quickly, gathering up the city’s wealth and fleeing Bursa precipitously. By the time the Tartars reached the Ottoman capital five days after the battle, it was largely stripped of its prizes—with the notable exception of the sultan’s wife, Zabina. The disappointing lack of plunder served to further spur the invaders in their traditional atrocities. Bursa became a scene of total destruction.

Over the course of the next half year, Tamerlane marched unopposed through Anatolia, subduing one town after another. He forced each to surrender its wealth; those that resisted faced certain massacre. Tamerlane’s greatest achievement was the capture of the Christian city of Smyrna. The Turks had failed in repeated attempts to take the city, and the Tartar emperor’s speedy triumph further vindicated his claim to be the champion of Islam. Following its fall, he butchered the Christian population.

Tamerlane moved quickly to reestablish order in Anatolia. Throughout its eastern half, he placed in power those emirs who had proven loyal to him during the previous campaign. But while Ottoman power was seriously reduced, Tamerlane had no desire to eliminate it everywhere. Instead, he divided what was left of the Ottoman empire among Bayezid’s sons in such a way that it could never challenge his authority again. The greatest portion of the empire went to the eldest son, Suleiman, by default. Since Suleiman had already escaped to Europe, Tamerlane simply allowed him to continue to rule from there.

The old capital of Bursa and its surrounding territories, meanwhile, fell into Isa’s lap. A final fragment, the territories of Rum around Toqat, ultimately ended up in Mehmed’s hands when he seized it from an already established vassal. Tamerlane could have easily destroyed him for the deed, but because Mehmed offered tribute, the emperor looked the other way. As for Bayezid’s other sons, Tamerlane released Musa to Mehmed’s custody in 1403 while Mustafa remained captive in Samarkand until 1415. But what of their father, Bayezid the Thunderbolt? According to the 16th-century English playwright Christopher Marlowe, in his play Tamburlaine the Great, Tamerlane went to great lengths to humiliate the captured sultan. As the story went, the emperor repeatedly mocked his prisoner, locked him in a cage like an animal, and even used him as a footstool. Meanwhile, Bayezid’s wife, Zabina, became the slave of a handmaiden. In Marlowe’s retelling, the sultan, in a fit of passion, committed suicide by smashing his head against the bars of his cage. Zabina likewise brained herself.

As fascinating and dramatic as this version of events was, it was almost completely false. Marlowe’s embellished account of Bayezid’s captivity, in fact, originated with Arabshah, a man who never ceased to point out Tamerlane’s unquenchable bloodlust although he painted a much milder picture than Marlowe. Arabshah described Bayezid as being placed in fetters rather than a cage; and although he at times hurled insults, Timur also showed sympathy and respect to the fallen ruler. On the other end of the spectrum, Sharaf ad-din Ali Yazdi, an Arabian sage who desperately sought to win the emperor’s favor, claimed that Tamerlane practically pampered the sultan and burst into tears when he learned of his former enemy’s death. He went so far as to write that Tamerlane had never wanted war and after the battle at Ankara planned eventually to restore Bayezid to the Ottoman throne.

This equally extreme version was also untrue. As is usually the case, the truth lay somewhere in the middle. Bayezid was indeed bound, but only following an attempted escape, and was never locked inside a cage. Depending on Tamerlane’s mood, Bayezid was sometimes treated as an honored guest and sometimes as a scorned prisoner. While he was never made into a footstool, he did suffer the humiliation of watching his harem paraded before him lubriciously during a feast in retribution for his previous remarks concerning Tamerlane’s wives. When Bayezid died a captive on March 3, 1403, apoplexy—not murder—was the most likely culprit. It can safely be assumed that Tamerlane held back his tears upon hearing the news.

Legacy of the Battle of Ankara

Ironically, what was most significant about the Battle of Ankara was its complete insignificance, remarkable considering the sheer size of the engagement and the reputations of the belligerents. Following the Tartar invasion of Anatolia, the old Ottoman Empire erupted into civil war. In 1404, Suleiman, strongest among Bayezid’s sons, crossed the strait into Asia in a bid to reunite the empire one year after Mehmed had defeated Isa to gain control of Anatolia. When Musa counterattacked, however, Suleiman’s strength slowly waned until, in 1411, he was captured and strangled. Two years later, Mehmed finished off Musa at Sofia and became Sultan Mehmed I, reconstituting the Ottoman Empire. His namesake, Mehmed II, would capture Constantinople in 1453 and bring Turkish power back to eastern Anatolia. Thus, the Battle of Ankara failed to alter history. It merely delayed it.

As for the victors of the battle, they disappeared entirely. In 1403, Tamerlane’s heir, Mohammed Sultan died, removing the best hope of keeping the immense Tartar Empire together once its aged emperor was dead. A year later, Tamerlane followed his grandson to the grave just as he was launching a campaign to conquer China. Without Tamerlane, the empire declined into a lurid memory. His glorious victory at Ankara accomplished nothing except assure Timur the Lame a lofty position among the world’s most successful conquerors. As such, Ankara remains a largely obscure testament to the futility of combining megalomania, territorial greed, and religious warfare.

Originally Published December 2009

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments