By Brandt Heatherington

It is a fact that war has sparked some amazing innovations. It has at the same time spawned incredible desperation. The attempt by the U.S. Navy in both world wars to construct seagoing vessels made of concrete would seem to be a combination of the two at first glance.

A hulking gray stone façade lay for years in the surf off Sunset Beach at Cape May, New Jersey. It appeared to be the skeletal remains of some strange vessel with the bow protruding upright from the water. The waves lapped its ghostly shape as if it was always intended to be a forlorn breakwater. This was the remnant of the SS Atlantus, a relic from one of the strangest programs the U.S. Navy has ever undertaken.

Concrete ships were not unheard of prior the Atlantus and her World War I-era contemporaries. The oldest known concrete ship was a dinghy built by Joseph Louis Lambot in southern France in 1848. The boat was featured at the 1855 World’s Fair. In the 1890s, an Italian engineer named Carlo Gabellini built barges and small ships out of concrete. Numerous small concrete boats were built in the England in the first decade of the 20th century, and one of these ships, the Violette, built in 1917, is now a boating clubhouse on the Medway River. This makes her the oldest concrete ship still afloat.

A Shortage of Steel

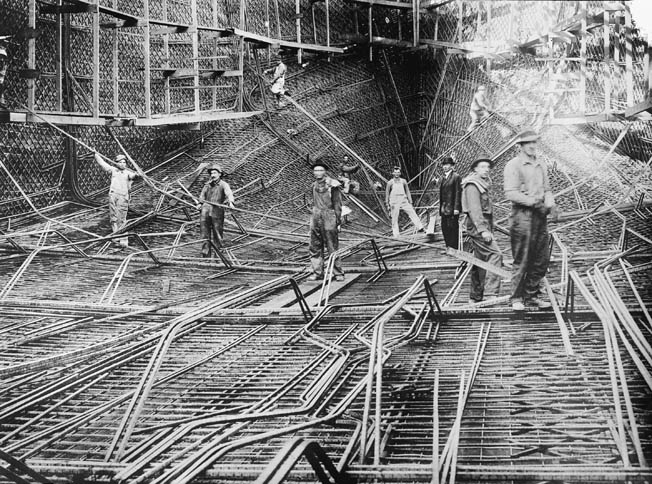

When the United States finally entered World War I in 1917, steel became scarce, and at the same time the demand for ships increased. The U.S. government invited a Norwegian named N.K. Fougner to head a study into the feasibility of building ships made of ferro-concrete, or concrete reinforced with steel bars. In August 1917, Founger had successfully launched the first cement ship, the 84-foot Namsenfjord, and the United States wanted to see what he could do to expand its fleet using inexpensive alternative materials.

Based on the study, President Woodrow Wilson approved the Emergency Fleet program, which commissioned the construction of 24 concrete ships for the war effort. The ships would be used for transport purposes, mainly as steamers or oil tankers.

Meanwhile, a businessman named William Leslie Comyn took the initiative and formed the San Francisco Ship Building Company to begin constructing the newly authorized vessels. The first American concrete ship, a steamer named the SS Faith, was launched in March 1918 and cost $750,000 to build. By the time the war ended eight months later, construction had begun on only half the fleet at a cost of $50 million, and none of the concrete ships had actually been completed. Several companies had joined the effort by this time, including the Liberty Ship Building Company based in Wilmington, North Carolina. Eventually, a dozen ships were completed and sold to private companies which used them for commerce, storage, and scrap.

What became of the World War I fleet was almost as intriguing and bizarre as the concept of concrete ships itself. The SS Atlantus was a steamer eventually purchased for use as a ferry landing. During construction of the landing, the Atlantus broke free from its moorings in a storm and grounded on the beach in Cape May where it remained for decades. The SS Cape Fear was another steamer. It collided with a cargo ship in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, shattered and sank, killing 19 crewmen. The SS Palo Alto was an oil tanker that was turned into a dance club and restaurant at Seacliff Beach, California, and is now a fishing pier.

Another tanker, the SS San Pasqual, was damaged in a storm in 1921 and eventually purchased by a Cuban company in 1924. It was run aground off Cuba in 1933 and used for a time as a prison. Later outfitted with machine guns and cannon in World War II, it was used as a lookout post for German submarines. Today, it is a 10-room hotel accessible by boat from mainland Cuba. The SS Sapona was a steamer sold for scrap but then converted into a floating liquor warehouse during Prohibition by a rum runner from the Bahamas. She was grounded off the shore of Bimini during a hurricane, and all the liquor inventory was lost.

A number of the ships were sunk as breakwaters or converted to floating oil barges in Texas and Louisiana. The SS Peralta was an oil tanker turned into a fish cannery and finally a floating breakwater in British Columbia, Canada. She is the last of the World War I fleet still afloat. The first concrete ship, the SS Faith, was used to carry cargo for trade until 1921, when she was sold and scrapped as a breakwater, also in Cuba.

Reviving the Concrete Fleet

With the advent of World War II, steel was once again in short supply. In 1942, the U.S. government decided to revisit the experiment with concrete ships, and the United States Maritime Commission contracted McCloskey & Company of Philadelphia to construct a new fleet, again to total two dozen ships. Thirty years of improvements in concrete would make this new fleet lighter and stronger. Construction started in July 1943, and the ships were built at an amazing rate with one being launched every month. They were appropriately enough named after pioneers in the science and development of concrete, including a Roman engineer named Vitruvius Pollio who lived in the first century bc.

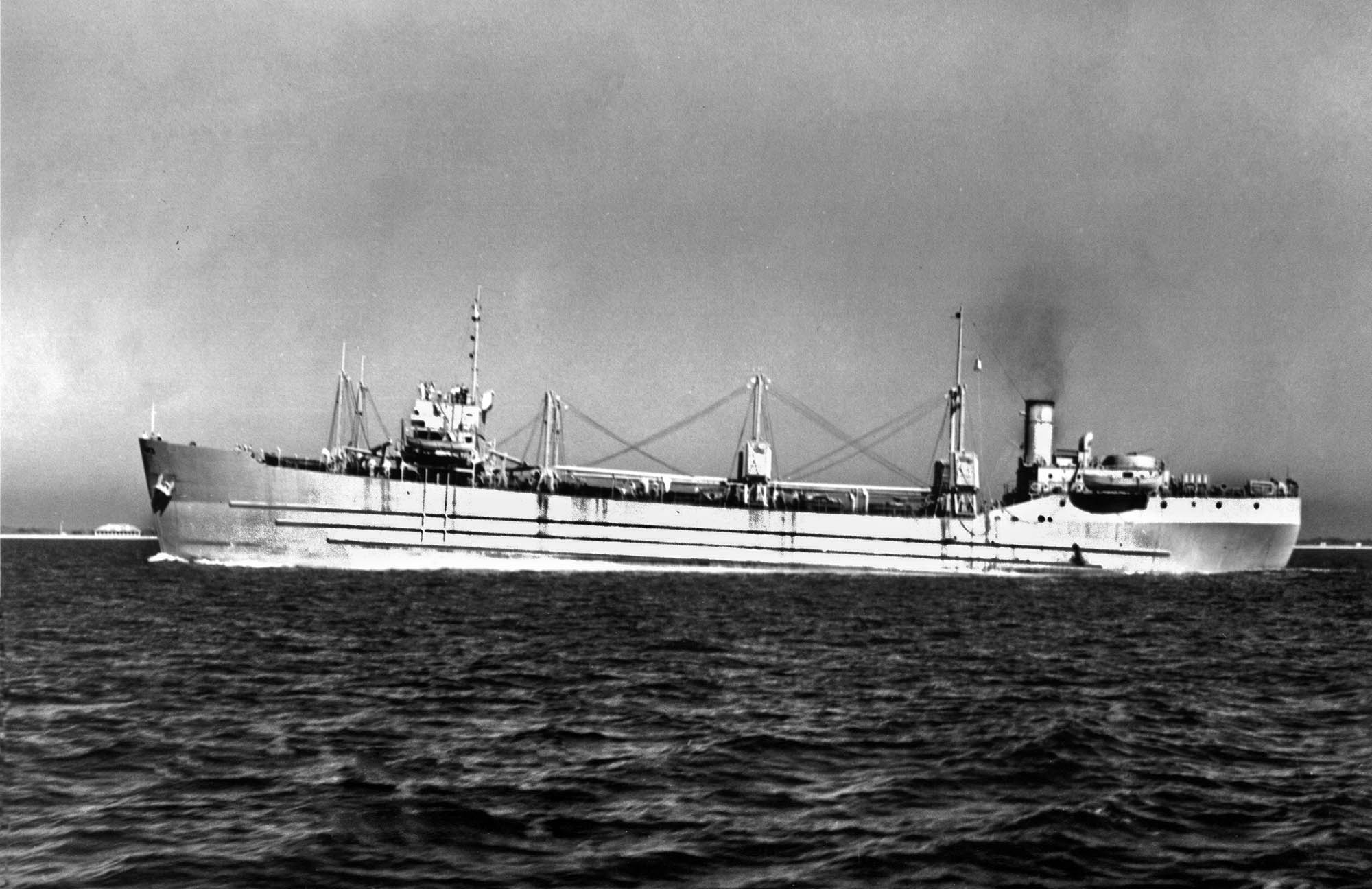

Two of these ships did see combat service. In March 1944, the SS David O. Saylor and the SS Vitruvius set sail from Baltimore for Liverpool, England, to join the fleet preparing for the D-Day invasion. An American merchant mariner named Richard Powers was on the maiden voyage of the Vitruvius. He was offered a return voyage aboard the luxury liner Queen Mary in exchange for helping to sail Vitruvius to England.

Powers went to the docks in Baltimore where the Vitruvius was moored. He said the ship was unlike anything he had ever seen. Upon boarding the vessel, Powers noticed it was made of concrete and he became concerned as to whether it would get him and his shipmates across the Atlantic. He said he felt better once he realized the ship’s hold was being filled with lumber.

“We left Baltimore on March 5, and met our convoy just outside Charleston, South Carolina,” Powers recalled. “It wasn’t a pretty sight: 15 old ‘rustpots.’ There were World War I-era ‘Hog Islanders’ (named for the Hog Island shipyard in Philadelphia where these cargo and transport ships were built), damaged Liberty Ships.”

A Panamanian ship built in 1901, and the other concrete ship, the David O. Saylor, were also part of the group. Powers said the motley fleet looked like a floating junkyard. The ragtag flotilla made the crossing to Liverpool in 33 days without incident.

Powers reckoned, “The U-Boats were not stupid enough to waste their torpedoes on us.”

“It was the 4th of July Multiplied Tenfold”

Once the Vitruvius docked, it was the subject of great curiosity, with many of the locals coming to the port to see it. Powers recalled that one old gentleman tapped the hull with his cane to make sure it was actually made of concrete as he could not believe it. One day, Army engineers came aboard with several cases of dynamite and set up charges in the holds. Vitruvius rendezvoused at Portsmouth with other ships destined to be blockships sunk as part of the artificial Mulberry harbors to form a breakwater and landing piers off the coast of France in support of the D-Day landing.

On June 1, 1944, the ship again headed out to sea. About two days into the voyage, the captain called all hands on deck and read a letter from General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied commander in Europe, telling the crew they would be making history by participating in the invasion of Normandy.

One thousand American merchant mariners were among the crews of the blockships. There were nearly 100 American and British freighters, from ancient tramps to comparatively new Liberty ships, making their way into the choppy English Channel at a snail’s pace of five knots. A low-flying German reconnaissance plane, U-boat, or E-boat would have been quite curious about the mission of these ships as almost every one of them bore obvious defects. Some had gaping torpedo holes in their sides, while the structures of others were mangled from collisions or mine explosions. But they limped along with an even more puzzling heavy naval escort of planes and destroyers, their mission and purpose surely a mystery to any observer. All the while they had their antiaircraft guns manned around the clock against attack. Perhaps their benign appearance served them well. Crossing the Channel on D-Day brought no harm to the Vitruvius and her companion vessels that were soon destined for a watery grave. The Army had stationed armed troops on board, but their services were not needed.

D-Day was cloudy, and the Luftwaffe had surrendered air supremacy over the Channel. Occasionally, a German plane would make a flyover and every ship would open fire with its antiaircraft armament.

Powers mused, “It was the 4th of July multiplied tenfold.”

The panorama that presented itself to the crews of the blockships off the coast of France was awe inspiring to Powers and his shipmates —battleships with heavy guns blasting the shoreline, destroyers, destroyer escorts, and every kind of landing craft imaginable. Those aboard the blockships had a bird’s-eye view of the landing craft heading for shore, the fighting on the beach, and the bodies floating in the water. Powers was glad to be on a ship even if it was made of concrete.

On D-Day + 1, the crew tried to maneuver Vitruvius to its assigned position, but German artillery prevented them from doing do. They tried again on day three with the same result. Finally, on D-Day + 4 the ship got into position and the crew was offloaded to an LCI (Landing Craft, Infantry). After several attempts, engineers set off the dynamite that sank the Vitruvius in the shallow water off Normandy, leaving about half the ship still visible above the waterline.

By the end of D-Day + 1, a total of 89 ships of this fleet of merchant has-beens had carried out one of the most difficult and dangerous operations of the Normandy invasion. The remainder of the fleet, including Vitruvius, did follow shortly thereafter. The concrete ships had been sunk a mere 1,000 yards off the beaches that comprised the hottest combat zones of the invasion. Their upper decks formed a steel breakwater, calmed the waves and swells, and allowed the thousands of smaller landing craft to hit the beaches safely to deliver soldiers and war matériel.

The End of the Concrete Ships

The crews were ferried to a troopship that took them back across the Channel to Bourne-mouth, England. By then the merchant mariners were hungry due to the extra time it had taken to sink the ships. They had actually run out of food aboard the Vitruvius and many of her sister blockships. The British fed the crews a meal of cabbage, boiled potatoes, and hard rolls, and Powers said they were grateful for it.

Thousands of Merchant Marine vessels supported the invasion by ferrying troops and supplies to the invasion beaches, but perhaps no other ships performed so unique and critical mission, intentionally designed end in their sinking. Military engineers saw no other way to form the critical breakwaters rapidly, and the lumbering hulks led by two of the concrete fleet filled the bill admirably.

True to the promise, all the blockship crews were put on the Queen Mary except for five who volunteered to stay in Liverpool as replacements for seamen killed or wounded. Richard Powers was among the volunteers, so after his epic ordeal he missed his chance to sail on the Queen Mary.

The fate of the remaining World War II concrete fleet was not as unique or entertaining as their predecessors of World War I. Nine were sunk as breakwaters for a ferry landing in Virginia, two are now wharves in Oregon, and seven are still afloat as part of a breakwater on the Powell River in Canada. The World War II fleet ended America’s experiment with concrete ships, one of the most unusual naval projects in history.

There is a holed concrete ship in the River Thames on the south coast near Greenhithe.

My dad served with US Merchant Marines in South Pacific during WW2. I remember he told us that briefly he served aboard a concrete ship, I don’t know the name of the vessel and dad is no longer around for reference. He remembered that the crew enjoyed working aboard that concrete ship because they found their quarters were much cooler than steel ships in the tropical climate.