By John Niesel

When the four members of the Japanese surrender delegation climbed aboard the deck of PT-375 on September 8, 1945, the boat’s skipper, Lieutenant Henry “Hank” Blake, directed the men to an open area on the forward deck where the Japanese could be closely watched for any signs of treachery.

Imperial Japanese Navy Vice Admiral Michiaki Kamada—the ranking Japanese officer in Borneo—and two other Japanese officers began to proceed to the designated spot. The fourth Japanese, a stocky, muscular enlisted man, stationed himself close to PT-375’s cockpit, effectively between the American sailors and the other three Japanese.

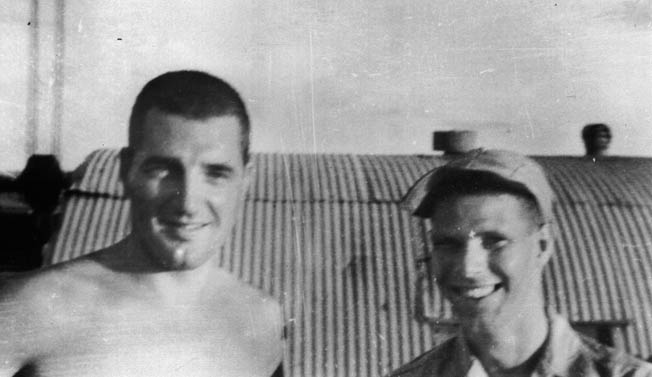

Hank, a no-nonsense PT boat captain—and a champion wrestler in college—confronted the stocky man who apparently was a bodyguard for the Japanese officers. “He was handling the officers like a bunch of chickens, taking half steps, and stopping them at certain points,” Hank recalls. “I wasn’t going to have any of that, so I yelled, ‘Hey buddy! Get your ass up on the bow or it’s going overboard! Right now! Or you’re going overboard!’”

The Japanese bodyguard, whether he understood English or not, caught the gist of Hank’s warning and quickly moved up to join the other three members of the surrender party. “We kept an eye on them,” Hank related, “but from that point on they didn’t give us any trouble.”

PT-375’s taxi mission, which occurred six days after the formal Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay, was the culmination of Hank Blake’s PT-boat career in World War II. Just how did the 25-year-old Pennsylvania native end up off the coast of Borneo, skipper of an 80-foot wooden boat loaded with 3,000 gallons of 100-octane aviation gasoline and bristling with weapons?

A Naval Officer in the Making

“I always loved the water—just loved the water,” Hank stated. “At one time, my parents, my brother, and I lived in a little furnished apartment in Albany, New York. While we were there, the Hudson River was dredged so ocean-going vessels could come all the way up to Albany.”

With big ships coming and going in his hometown, just how powerful was the pull of the sea on young Hank’s impressionable mind? “I was just a kid,” he explained, “and my mother wanted to be sure I received proper religious training. So she would give me a nickel for spending money and send me away, push me out the door, to go to a Baptist church that was a block down the street.

“But I’d take that nickel, go down to the waterfront, and buy a bag of peanuts. I’d feed the peanuts to the birds so I could be around the water! I just loved the water … and I wanted to be in the Navy.”

Hank was bitten by the sea bug, and when the United States entered World War II there was no doubt regarding which branch of the service he would be joining. Three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, he decided to skip graduation from Lock Haven State Teachers College (now Lock Haven University) and enlist.

“Leaving college early meant I was going to miss the graduation ceremony,” Hank said, “but I had enough credit hours to get my degree, and I graduated cum laude. Following my induction and basic training in March 1942, I was assigned to the midshipman’s school at Columbia University in New York City. My bachelor’s degree from Lock Haven was in health and physical education, so I was assigned to instruct drill, basic boat handling, physical training, and swimming. Instructing swimming was a great feature for me due to my love of the water.”

Hank’s skill in the water was apparent to the officer in charge of the program, and he gave Hank free rein to develop the swimming program. “They asked me to take this one platoon on a recreational swim. I think I had 36 guys in there, and 30 percent of them couldn’t swim the length of a swimming pool, yet these guys were going to be naval officers!

“So I right away got busy and hustled up some other swimming pools in the Columbia University area and enlisted the help of other fellas with swimming skills equal to mine. We taught not just recreational swimming, but also what to do during evacuation and rescue in the water. There are a lot of things you can do to stay afloat using life preserving equipment once you are thrown into the water.”

Hank’s swimming program for the midshipmen demonstrated his initiative and organizational skills, vital wartime capabilities that did not go unnoticed by the commanding officer. Hank continued, “So on the basis of the quality of the swimming program, the CO—I don’t remember his name, but he was a commander in rank—said, ‘You have officer quality. Are you interested in a commission?’ Well, I was happy with my situation at that point: I was married and had one child. But the more I thought about it….”

Hank seriously considered the offer to become an officer in the United States Naval Reserve. “The commander had written a letter of recommendation for me, and when he handed it to me he said, ‘The day you want to become an officer, you turn this letter in and you’ll have gold braid hanging from you!’ And that moved me out of the physical fitness program and on into officers training.”

Service on a PT-Boat

The thought of becoming a naval officer was an exciting and interesting prospect for Hank, but the initial coursework was anything but. “I was then going to classes that I had previously been teaching,” explained Hank, “so it was rather boring! But anyway, I eventually finished with officer training school. That’s when I put in a request for PT-boat service.”

Why did he choose the PTs? “Oh, just the excitement of it,” he stated. “In school I had been active in athletics, football, and wrestling. I liked the excitement. I liked to fight. From college I also knew a lot of All-American football players who joined the PTs. I knew I didn’t want to get on some tub that goes out and changes the buoy markers in a harbor or something like that! I wanted to get into the action, so I applied for PT duty and that’s what I got.”

If Hank’s explanation of why he chose the PTs seems a bit gung-ho, it’s because he was. It was just this type of aggressive, can-do spirit that the U.S. Navy looked for when choosing candidates for motor torpedo boat command.

Life on a PT boat during wartime could be perilous, and with a small crew of 14 to 17 men under one’s command, leading by example and being willing to take the war to the enemy without hesitation were critical attributes for a successful PT boat captain.

Learning to Handle PT-Boats

Once Hank received notification of his acceptance into the Navy’s Motor Torpedo Boat program, it was time to travel to Melville, Rhode Island, where the MTB School was located. As with many cities and towns with a prominent military presence nearby, available housing was in short supply. “I moved my family up to Newport where we lived in a one-room apartment. I mean everyone was crowded! We had one of the second-floor rooms in the building,” he remembered. “Melville was just up the river from Newport, but with my training I was only able to get home every third night.”

Hank was busy with the numerous classes taught at the school—courses on navigation, gunnery, engine mechanics, torpedo maintenance, and boat handling among others. He did well in all of his courses, but his performance in one area really stood out. “Once our training was over, a lot of my classmates were immediately assigned to overseas boats,” Hank recalled.

“But I was assigned back into Squadron 4, which was the training squadron based at Melville. I was 24 years old at the time and did some teaching of various courses, including some experimental work with radar tracking. But soon I was turned over to boat handling. I was exceptional at it, had a real knack for it. Boat handling came naturally to me. So I put up with that for a while.”

Overnight trips out to sea were one reason Hank didn’t make it home to his family’s one-room apartment each night. “Thorough training of new recruits included a trip from Melville to Bayonne, New Jersey, where Elco was building the boats,” Hank said.

“The purpose of these trips was to acquaint the rookie guys with long-distance navigation and nighttime travel with the PT. Along the way we encountered all kinds of lights, buoys, and signals of all sorts, and traveling at night was an educational experience for the recruits. Once we reached Bayonne, they got to observe the construction of new boats.”

Hank continued as a boat handling instructor until he was assigned as second officer on a boat at Newport. A lot of the time his skipper was not present, so he was basically a second officer who handled the majority of the boat work. “After a given time, I was assigned to overseas duty and given notice to go from Newport to San Francisco for shipping out. I took my family home for Christmas in 1944, and on December 29, I received change-of-duty orders from Squadron 4 to Squadron 27.”

Joining Squadron 27 in the Pacific

Hank left in January 1945 for Subic Bay in the Philippines. He shipped out on a converted cruise ship that had a lot of soldiers but few sailors. “We went to some of the larger islands on our way across the Pacific, then to Leyte Gulf, and on to Subic where I joined Squadron 27.”

At the time of Hank’s arrival, Squadron 27 was under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Henry “Stilly” Taylor, a veteran of the early PT boat actions in the Solomon Islands. Ron 27 (the PT crews referred to a squadron as a “Ron”) had arrived in the South Pacific in May 1944, when the boats idled into the motor torpedo boat base on Treasury Island off of the coast of Bougainville.

Over the next two months, Ron 27 engaged the Japanese in the waters around the islands of Bougainville, New Ireland, and New Guinea. In August 1944, the squadron moved to Palau in the Mariana Islands, then in late December 1944 it received orders for the move to the Philippines.

Ron 27, comprising PT-356, PT-357, PT-358, PT-359, PT-360, PT-361, PT-372, PT-373, PT-374, PT-375, PT-376, and PT-377, saw action at San Pedro Bay and Subic Bay, where the boats engaged numerous enemy vessels and shore targets. Once Subic was clear, Ron 27 moved in.

“At one time Subic Bay had been a Navy coaling station,” Hank said. “In the past, when the Navy had steamships rather than oil-fired ships, they had to have locations all over the world where the ships could fuel up with coal. Subic was one of them. Sometimes our boats would tie up to the old coaling dock if we weren’t able to nest alongside our tender.”

Hank’s arrival at Subic Bay was quickly followed by an event that was occurring less and less frequently in the southwestern Luzon area. Even though the U.S. Army Air Forces and Navy pilots had won air superiority in the skies over the Philippines, there was still an occasional air raid.

“I remember almost the first night or close to it,” Hank said. “We had a red alert and went to general quarters. A tremendous searchlight onshore was shining straight up on a Japanese bomber that was sailing over, and this P-38 went straight up the shaft of light and caught him. I’ll always remember that.”

From Subic the boats patrolled south to the waters outside Manila Bay, and on February 3, 1945, Ron 27’s PTs became the first Allied war vessels to enter the bay since the surrender of U.S. forces on Corregidor in May 1942.

PT-375

Hank was given orders to join the crew of PT-375 (an 80-foot Elco boat that was placed in service on August 10, 1943). At the time of Hank’s assignment, PT-375 was under the command of Lieutenant Patrick Requa. “I was riding second officer at that time,” Hank said (riding second officer meant that he was assigned to a boat with an existing skipper and executive officer), “and we did nighttime patrols, cruising work, and that sort of business around Manila Bay and Corregidor. Once Manila Bay was clear we operated out of there.”

Even though the bay was in American hands, the surrounding jungle on the large island of Luzon wasn’t completely clear of enemy personnel. Japanese soldiers attempting to escape from Corregidor and the shoreline surrounding Manila Bay were often spotted in the waters offshore, and the deck log for PT-375 states that in March 1945 a Japanese soldier was caught in the boat’s screws while it returned from a nighttime patrol. Body parts were observed in the boat’s wake.

Another entry notes that five Japanese soldiers were encountered in the water during another patrol and, after refusing to surrender, “were eliminated to ensure the safety of the boat.”

Hank also recalled seeing Japanese attempting to escape the bay area by swimming out to sea. “Corregidor was just a great big rock with a little bit of brush around it, but not much. Japanese would get out of the brush around Manila Bay and start swimming out toward Corregidor. If they reached it, there really wasn’t any place to hide. They’d get ashore, then just keep a low profile.

“There was also one particular place near the bay entrance, a large rock that was about the size of an automobile, with a radio antenna tower on it. Some of the Japanese would come out of the jungle and swim out into the water. And when they didn’t get picked up by a secret Japanese submarine or something, they’d get onto that rock, and, with no place to hide, start to climb that antenna pole. I don’t know where the hell they thought they were going! But some of them were taken prisoner off of that rock.”

Ron 27’s patrols also took prisoners near the numerous sunken ships strewn throughout Manila Bay. Small groups of Japanese would sneak aboard the hulks and, using the wrecks as cover, snipe at any Americans passing by. Along with other PT boats, PT-375 would take its turn making firing runs on the ships, afterward commenting in the log book, “Run negative” or “Run positive. Observed blood in the water,” or “Jap bodies visible.”

A Crew Member’s Close Call With Shrapnel

As the Americans pushed farther into the island of Luzon, however, targets of all types became fewer, so the PT crews turned their attention to other tasks. “It was evident by this time in the war that gunnery was much more important than torpedoes,” Hank noted. Frequent runs out to sea for gunnery practice against floating and aerial targets reinforced this emphasis on the PT’s primary role as a gunboat.

For all of Hank’s time on PT-375, attacks were carried out exclusively with guns, and one particular engagement stands out in his mind. “I was Pat Requa’s executive officer. During a nighttime operation, under complete blackout, we engaged the enemy. I was at the wheel, and Requa was manning one of the twin .50-caliber machine guns located adjacent to the cockpit.

“There was shrapnel flying around. Even though we were under blackout conditions, I could see a rip in the knee of Pat’s uniform. I put an enlisted man at the wheel and told Pat, ‘We are going below to examine your knee.’ There was great concern in Pat’s voice—knowing he was due to go home to get married—when he told me, ‘The hell with my knee … I think my dick is gone!’

“When we got below in the light, it was obvious that a piece of shrapnel in a straight downward flight had entered the top of his fly, and produced only a blood blister right at the point where his penis was attached to his trunk. The main bleeding was coming from an injury to his leg, which was caused by a second piece of shrapnel. The blood was running out over his shoe.”

Requa personally directed medical attention to his wound while Hank went back to the wheel and radioed for the location of the nearest hospital ship. He then headed the boat on a course to the ship and was able to immediately obtain full forward speed.

“We dropped Pat at the hospital ship and returned to duty. Since he was due to go home to be wedded, the path of the shrapnel entertained the crew aboard the boat for quite a while!”

Tending to the PT

In June 1945, the boats of Squadron 27 were ordered to the southern Philippine island of Samar to prepare for patrols supporting the upcoming invasion of Borneo.

“Part of the preparations involved cleaning and painting the hull of the boat,” Hank said. “Our squadron was assigned to the USS Varuna, an LST [Landing Ship, Tank] that was converted to PT-tender configuration. It had a cradle [known as an “A-frame”] that the boat could float onto, and we were hoisted out of the water so we could service the bottom of the boat. You were given a number of hours on the tender to clean off the tremendous growth caused by the ocean on the bottom of the hull.”

If left unchecked, the growth would create enough drag on the PT’s sleek hull to

significantly reduce the boat’s top speed, and since speed was one of the PT’s primary strengths a clean hull was essential to mission success and the safety of the boat and crew.

After PT-375 was covered in a fresh coat of camouflage paint, it was out to sea for more trials. “We went out and tested our gunfire, tested the accuracy of our navigating equipment, ran the boats at different speeds,” said Hank. “Got them in shape for the move to Borneo.”

At this time Hank experienced a change in duty. “At Samar is where I became skipper of PT-375. What the Navy did was, they’d bring in an ensign to train, so for a short period there would be three officers on a boat. As soon as they thought the third officer was fit, the top officer would go home, the XO would be promoted to skipper, and the third officer would become executive officer. That’s how I became boat captain when we were based at Samar. I was second in command, then Pat Requa got his orders to go back stateside.

“Another thing, the Navy’d send us kids, just 16 or 17 years old, never been away from home at all. When they wrote letters, an officer would have to censor them, so the crew would put the letters on my desk. This one kid from New Jersey was really excited about being on a boat, and he wrote all kinds of letters home.

“Now, on a PT, you had all of these enlisted men using one head at the bow of the boat for shaving and toileting. It was a lot of men in a cramped, condensed area using one stainless steel sink and toilet, so it could get really messy. Cleaning the enlisted men’s head was the nastiest job of anything on the boat, but everybody had to take a turn at it.

“I put this boy from New Jersey on there right away to break him in—and he did such a magnificent job! I put him on there, and I’m telling you, that head looked like a jewelry store when he’d come out from cleaning it!

“So when I called him up in front of the rest of the crew, complimented him, shook his hand, put my arm around his shoulder and said, ‘We just haven’t had anybody that liked that job,’ he said, ‘Well, nobody is taking it from me!’ He assigned himself! And then I censored his next letter home, and you should have seen the way he boasted to his family about being captain of the head!”

Shortly after his promotion to skipper, Hank and PT-375 departed for the last major Allied invasion of World War II, the invasion of Borneo.

Supporting the Invasion of Borneo

The ground phase of the assault began on July 1, 1945, when Australian troops waded ashore. The Aussies had requested that the United States provide naval support for the operation, and as part of that effort four PTs of Ron 27 arrived in the area on June 27 prior to the invasion. The remaining eight boats arrived with the USS Varuna on the day of the invasion.

Initially the boats operated out of nearby Tarakan, but once the Aussies had pushed farther inland on Borneo the PTs moved to the island itself to better provide effective, close-in support.

“The entire squadron was assigned to a base at Balikpapan,” Hank related. “From there we made nighttime patrols along the coast and to neighboring islands. The strategy at that time of the war was to prevent the Japanese from supplying and rescuing some of their legions in the area. It was our duty to halt all enemy traffic, day and night, and to destroy armaments positioned along the coastline and on neighboring islands. We received specific assignments if there was a Japanese radio station or other installation that needed taking out.

“Also, it was obvious that the Japanese were supplying weapons to the native populations on the islands, and it became the duty of the PT squadrons to halt this traffic. This was done as gunboats, not torpedo boats. We made lots of nighttime raids, did practically all of our work during dark hours. From time to time the Japanese attempted to provide armaments by submarine and surface vessel. We’d encounter small Japanese ships called maru … We’d call them ‘Snafu Maru!’”

The Japanese employed all types of small craft from canoes to luggers and lighters in attempts to travel to or from the islands, but PT-375 and the other PTs drew the noose ever tighter around Borneo, choking off anything that floated.

As had occurred elsewhere in the Pacific over the previous three years of warfare, the PTs were successful at minimizing the delivery of supplies to the Japanese on Borneo, as well as preventing the escape or evacuation of the beleaguered enemy personnel.

Hank also credited the soldiers on shore with the success the Allies experienced there. “A very important element of this containment was provided by the Australian land forces,” he stated.

Letting the PT Roar

On many occasions throughout the Borneo campaign, the Americans and Australians cooperated operationally, coordinating Aussie air, ground, and naval support with U.S. Navy forces. As the Japanese resistance on Borneo steadily declined, the PTs went hunting elsewhere for enemy targets.

“From our base at Borneo we’d go over to the Celebes Islands,” Hank explained, “to clean up some things the command wanted taken out. I had one daylight patrol where they sent a fleet officer to ride along. I don’t know his exact rank, he was well above my rank as a lieutenant. Anyway, he came aboard my boat and said that there was located someplace on one of these small islands a Japanese floatplane installation.”

The floatplanes were a hazard for the PTs because they would fly at a high altitude so they couldn’t be seen or heard, but they could spot a PT boat’s wake. “We had mufflers on the boat that controlled the exhaust noise from the Packard engines. If you were rushing between islands, you would put the mufflers wide open and just roar! But if you were snooping around there at, say, six knots, you could muffle all of your sound down into the water. But the boat still left a wake, and it was that wake that was giving the Japanese a good look at PT boat traffic. So with that fleet officer aboard, we headed out to look for possible air stations for these damn floatplanes.

“As we were making headway—since it was daylight we knew we were vulnerable, so we just left the throttles wide open—we knew the Japanese knew we were there. If they wanted to come out and meet us, that was okay. So anyway, we were roarin’ along, and all of a sudden there was this awful sound coming from the stern of the boat. Now, these PT boats had direct drive; the engine output didn’t go through any gear reduction at all. We had three V-12 engines, and once they were put in gear you were going either forward or you were going in reverse.

“Well, all of a sudden we heard this tremendous scream, and one of the prop shafts—the center shaft—had fatigued. When it snapped it dropped the prop off, too, so the center Packard was running at full speed with no load whatsoever on it! We quickly shut it down, turned around, and headed back toward base; we had no trouble because we still had two fantastic Packard engines.

“When I limped back into base, we went to our tender, a big, long LST that was specifically equipped to take care of two PT squadrons. We nested alongside of the tender during daylight; if you couldn’t dock along shore, then you nested against the side of the tender. So I took the boat gently to the tender, and it turns out they did not have a shaft and screw that was compatible with our other two. The screws were about 28 inches broad, and the supply officer on the tender said, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t want to send you out with just two screws working.’ He said, ‘The only thing I have in stock is a set of racing screws.’

“I said, ‘Put her on, babe!’ That worked out all the better for me because that definitely made the 375 the fastest boat in the squadron. As a result, I got some errands to do when higher-up officers needed to be moved from place to place, or were visiting a certain ship or base. So for daytime work we did a little bit of taxi service, but then at nighttime we definitely were hooked into hits over in the Celebes Islands or hits along the shores of Borneo.”

The Threat of Stormy Seas

Hank also delivered native scouts to enemy-held shores. “They were Netherland East Indies Scouts,” Hank recalled. “I put them ashore for intelligence gathering on the Japanese. We’d run the boat up on the shore and drop them off.” Hank quickly realized that the native islanders were no fans of their Japanese occupiers. “The Japanese forced the natives to squat in their presence,” he said. “They couldn’t stand. That really pissed me off.” The native peoples of Borneo wouldn’t be squatting for long, however. Time was running out on the forces of Imperial Japan in Borneo and elsewhere.

The Japanese weren’t the only threat encountered by the boats of Squadron 27. The weather in the Southwest Pacific offered challenges of its own. “When we went to attack Borneo, there was a period of time when the weather was terrible,” Hank said. “Our squadron arrived at this one spot north and a little east of Borneo’s shore. Every single night we had a storm there where we were anchored. When the boat was underway, there was no shelter for anybody who was at the wheel in charge of operation, or studying a map, or something like that.”

The PT cockpit was open to the elements, which provided excellent visibility. However, all hands topside were fully exposed. “In the daytime,” Hank continued, “the sun would be so damn hot that some of the boats rigged a canvas, like an awning, over the foredeck. If they didn’t take it down before a storm hit, the wind would just take it and go!

“As for being in any stormy seas, when traveling from island to island we were used to being in some really deep swells, I mean to the point where you would start to climb steeply up the face of the swell.”

Hank’s experience with boat handling allowed him to stay on course while plowing through such heavy seas. “You would have a course which was in your mind and set in your compass, and you would use the wheel to keep the boat headed in the right direction,” Hank explained.

“Sometimes these monster waves would come one after another, where you would be climbing, climbing, climbing, and you’d get to the top where the wave would drop out from underneath you, and then you’d slam down. There were elbows, knees, and legs broken on deals like that, and especially the filaments in light bulbs!

“Anyway, the standard technique—if you were paying attention—was, as you’re going up one of these big rollers, you get almost to the top, and then throw the boat into a right hard rudder. That would kink the head of your vessel to the right, and then you would slide down the other side of the swell on your stern instead of coming down with a slam. Otherwise it would be like being on the end of a diving board with somebody jumping behind you.

“When the next big roller hit, you’d go hard left rudder at the crest of the swell so that when you straightened out you had compensated for the last hard right you made.”

War’s End

“As far as storms we were in, I remember one day a member of the crew was listening to a ballgame on the radio during the afternoon, before we headed out on the night’s patrol … and we heard the war was over.

“The next day we were asked to make a run to the Celebes. So we headed out that night with another boat commanded by Mel Everingham when a hell of a storm came up. I called him up on the TBS (Talk Between Ships) and said, ‘Suppose this [storm] was at Melville? Suppose we hit weather like this at Melville?’

“He said, ‘We’d call base, secure from patrol, turn around, and go home.” I said, ‘So what the hell are we doing out here anyway? The war’s over!’ So he did! He called the base, we turned around, and we did not complete that patrol. Mel was one of the good guys. We had almost 100 percent good guys; no chickenshit officers, you know? If we got one coming in, we started calling him ‘Chick’ right away. He knew his time was limited!”

As announced on Hank’s shipmate’s radio, the war was indeed over. Across the Pacific, as had happened across Europe when Nazi Germany capitulated, men celebrated in various ways, some noisily, some quietly. What did Hank and his crew do?

“Well, my squadron commander, Stilly Taylor—who by the way was pretty informal—had 12 boats in his squadron,” he says. “There were something like two officers and 14 or 15 enlisted men on each boat, and someplace or another he got some cases of cold beer.

“He called me in and said, ‘Blake, you’re the only man in the squadron who doesn’t drink.’ So he said, ‘You’re in charge. Every man in the squadron gets three or four cans of beer, but open them all! Don’t give anybody else a can!’ I kept it the way he wanted it; I got it all handed out. Everybody had four beers. There was no shooting—and I got drunker than a skunk!”

Hank’s beer delivery was no doubt gladly received by the PT crews, making him a popular guy for a day. And even though the small crews and close quarters of PT service tended to lead to informal relations between officers and enlisted men, with his own crew Hank was a by-the-book skipper, no nicknames for him.

“I was either Mr. Blake or Captain,” he said. “I enforced the discipline. BUT … we’d take a life raft and put it overboard, and I would go in the water with these guys and play ‘King of the Raft.’ I’d throw the raft all over the place. I was an exceptional wrestler and an exceptional swimmer.”

Taking the Surrender of the Japanese

PT-375 may have been Ron 27’s beer delivery vehicle, but that’s not the reason she was chosen to transport the Japanese surrender party on September 8, 1945. She was chosen for her speed. Ever since the installation of the racing screws, she had proven time and again that she was the fastest boat in the two squadrons assigned to the USS Varuna. “We always raced!” Hank declared. “Every morning returning from patrol we’d see which boat was the fastest. That’s how I got the job taking the Japanese to the surrender ceremony.”

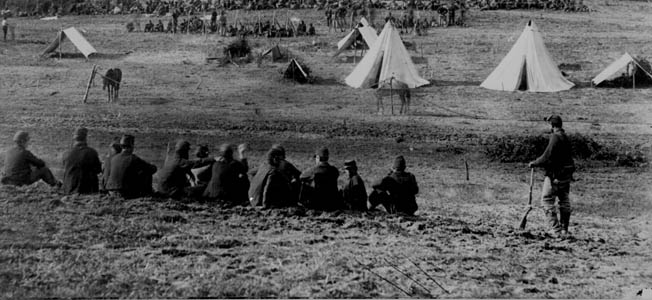

After the Japanese surrendered unconditionally aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, formal surrenders had to be arranged for the Japanese forces that were still scattered across the vast Pacific. On the morning of September 8, 1945, Ron 27’s commander, Stilly Taylor, led seven boats including PT-375 to Borneo’s Koetai River delta for a rendezvous with the Japanese surrender party.

“The naval officer in charge of this deal called down and said he wanted the fastest boat to go pick up the Japanese surrender party,” Hank remembered, “and his direct order to me was, ‘Give the bastards a ride’ [meaning a rough ride]. Now that was no problem because there was almost always at least a five-foot sea running between the coast of Borneo and the Celebes group, which was many miles away. There was a force of water down through there that poured on down into the seas below Australia. We also didn’t receive any orders about being polite or anything to the Japanese.

“They were brought down the river to the delta on a little wooden Australian riverboat, and we could see four Japanese aboard—three officers and a fourth that was a bodyguard. Anyway, we had these huge mufflers on the stern, so we never wanted anybody, ever, to approach us from the stern because if they crashed out on it you had no way to silence your nighttime patrols. So sure as hell, this Australian guy who was handling the riverboat came right in and almost got on our mufflers. I waved him off and told him to get around forward on the bow.

“After he swung around, the Japanese came up off of the riverboat, and there was no saluting, no formalities. I wanted them farther up on the bow, and that’s when the bodyguard started to stall along, so I was nasty with him; but I didn’t get any complaints from our higher-ups afterwards. I took the Japanese to an Australian warship [the frigate HMAS Burdekin], dropped them off, and that was it.

“Shortly after that, we received orders to take our boats back to the Philippines for decommissioning. The sad thing about that was, you loved your boat, and you knew you were saying goodbye.”

The Best Attribute of Hank’s PT

After the surrender run, Hank’s time with PT-375 was limited. With her racing screws and sleek hull, he would always remember her for her exceptional speed.

“The boat and all of the armaments functioned perfectly,” he stated. “Other than losing the center shaft and prop when the crystallized shaft broke, there weren’t any major problems.” Of course, had the shaft not failed, PT-375 would not have ended up with her racing screws.

“From a speed of seven or eight knots, she’d get up to full speed pretty damned fast, even when fully loaded,” Hank recalled fondly. “And with those Packards at full throttle, it sounded like all hell broke loose!”

There was no doubt PT-375 was a good boat. However, as Hank spent much of his time at Melville as an instructor with Squadron 4 on Higgins-built PTs (Higgins and Elco were the two primary manufacturers of PT boats for the U.S. Navy in World War II), the question begs to be asked: what was his favorite attribute of the Elco PT boat? Was it the graceful lines? The speed? The drier ride as compared to the Higgins design? For Hank, it was much simpler than any of these.

“They had ice cubes,” he explained. Ice cubes? Yes, the Elco PTs had small refrigerators in the tiny galley, and the availability of ice cubes to chill a drink in the heat of the tropical Pacific was an invaluable luxury for sailors with few such things, and a cooling touch of home for men at war.

The Fate of PT-375

Neither her speed nor ice cubes could save PT-375 from the fate that awaited her and many other PT boats at the war’s end. “The Navy processed every single knife and fork and spoon, anything they could save on the boat. All processed,” Hank said. “When all of that processing business was done, then they took the crew off. Now I had myself and another officer and a boat that had no equipment and no crew! After a couple of days, they took my XO away, and a couple more days and they took PT-375 away. From there I went into temporary officers quarters.

“I learned later that they took the boats around to a shoal somewhere off of Samar and set them on fire. Burned them up.”

PT-375 and the U.S. Navy’s more than 500 motor torpedo boats had served their country well during a time of immense danger and difficulty, and men like Hank made sure the boats were used to their full potential, thereby making an important contribution to the victory over tyranny and fascism during World War II.

“Since it had to be done, I’m awfully proud I had a chance to do it,” Hank said. “I don’t remember ever complaining about what I was ordered to do during my almost four years in the Navy. I just damn well did what I had to do, got it done, and figured sooner or later I’d be able to resume my life the way I wanted.”

Fortunately, that is exactly how things worked out for Hank Blake, due in part to PT-375, the fastest PT boat in Borneo!

Can there be possible to locate the exact location in Samar, Philiipines where the PT boats had been burned.

At age 95 there are many recollections and the worst was when

a crewmate was hit by a sniper. First aid was applied and the

Captain ran full speed to get to the hospital. This included putting

a wet rag on the governor which limited continuous running at

full speed. The ship mate bled out before reaching shore.

This story was not told to his wife of 70 years until recently.

He remembers eating with officers on the freighter which carried

four new PT boats to the Phillipines. (they were served better food.)

Happy New Year to all! I have just run across this wonderful article and enjoyed it so much. My father, Samuel Moody, Lt. Cmdr (jg) nickname on the boat “Moose”, served on several PT boats in the Philippines during WW2. He was from Richmond, VA. Unfortunately he died from cancer when I was 11 so we didn’t get a chance to hear the “real” war PT boat stories because we were too young. But he talked occasionally about the “everyday” life in the service. including trading with the Filipino’s the free cigarettes the US Navy were issued for T-shirts.

Best wishes to you,

Katherine Moody Brooks

Harry, do you remember the name of the crewmate who was hit by the sniper?