By Christopher Warner

March 24, 1945. The green light flashed from the C-47 tug plane, prompting the glider pilot being pulled behind it to release his tow rope over Landing Zone N, just east of the Rhine River. A steady barrage of German antiaircraft flak blackened the sky as tracer bullets ripped through his rickety Waco CG-4A’s fabric-covered fuselage. Making matters worse, thick smoke and haze blanketed the congested LZ, concealing the bevy of wrecked gliders and scrambling troops below.

More bad news: enemy snipers and flamethrowers waited below in a field laced with rows of ditches and barbed wire. Nonetheless, the pilot had to land quickly and at least give himself a fighting a chance on the ground. In all previous combat missions, American glider pilots suffered some of the highest casualty rates of the war. Surviving this corner of hell would be no different.

Operation Varsity, the airborne element to British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery’s ground assault across the Rhine River, Operation Plunder, involved more than 4,000 Allied aircraft, including 906 American CG-4A combat gliders, and became the largest, single lift airborne operation in history. It would also be the last major airborne offensive of World War II.

Allied glider pilots faced an especially daunting challenge: deliver heavy equipment, troops, and medical supplies behind well-fortified enemy lines in nonpowered, slow-moving aircraft made of canvas, plywood, and metal tubing. Once again, high casualties were expected.

The men flying these “Silent Wings” were a unique breed of soldier, serving as both pilot and grunt soldier—an unenviable position that ostensibly doubled their odds of being killed. Additionally, the glider pilots’ primary duty was returning to their air bases as soon as possible to be available to fly another mission.

Like the aircraft itself, glider pilots were considered expendable. In fact, the men weren’t even given parachutes because their “flying coffins” flew either too low to jump or too high for the pilot to survive the fall.

Also setting them apart, glider pilots wore a hard-earned, silver-winged pin stamped with a capital “G”—a letter that would also become synonymous for “guts.”

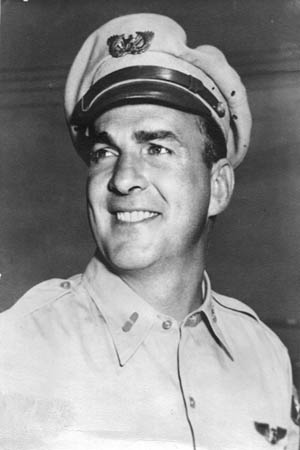

One of those pins belonged to my great uncle, Flight Officer Tom Warner who, on that fateful March afternoon, unhitched from his tow plane and began punching out the plexiglass side window panel prior to touching down. It was a deft maneuver that allowed him to rapidly exit the glider—providing that he survived the controlled crash landing or wasn’t killed by ground fire.

After the war, General William C. Westmoreland had this to say about the dangers experienced by glider pilots: “Every landing was a genuine do-or-die situation often in total darkness. They were the only aviators during World War II who had no motors, no parachutes, and no second chances.”

Like many young men living in the Depression era, Tom Warner struggled to find gainful employment while yearning for something more out of life—anything to replace the daily humdrum and frustration of deadend jobs. The attack on Pearl Harbor changed everything. Warner soon enlisted in the newly formed Glider Pilot Program under the command of General Henry “Hap” Arnold.

Germany had been the first to utilize gliders in combat, benefiting indirectly from sanctions of the Treaty of Versailles that prohibited the Germans from having an air force. However, since the treaty didn’t prohibit the production and use of unpowered aircraft, glider-flying clubs flourished throughout the country, producing the core of future Luftwaffe pilots.

In the spring of 1940, the combat glider made its debut at the Battle of Fort Eben-Emael in Belgium. The enormous, heavily armed garrison, encircled by a moat and thought to be impregnable, stood tall as an imposing roadblock to Germany’s Blitzkrieg across Europe. As the brainchild of Hitler himself, the audacious plan intended to showcase the combat glider’s landing precision and hauling capacity with only limited manpower.

The assault exceeded all expectations. At dawn on May 20, nine DFS-230 gliders carrying a scant total of 70 assault troops landed on top of Eben-Emael’s earthen roof, catching the unsuspecting Belgians completely off guard. Twenty minutes later the fort surrendered—and just as quickly established the glider’s stealth reputation. The rest of the world took notice.

A year later, however, the Germans ironically deemed glider-led assaults too dangerous after suffering heavy casualties in a hard fought victory at the Battle of Crete. Nonetheless, the Allies charged ahead to develop their own glider fleets.

General Arnold’s plan initially called for using only officers from the newly formed U.S. Army Air Forces or enlisted men who met specific criteria with flying experience. However, with America ramping up for war, power pilots couldn’t be spared, and there simply weren’t enough qualified men available to fulfill the quota of 6,000 glider pilots.

A hastily arranged public relations campaign was launched to find recruits—and fast. From state fairs to college campuses and across all military bases, the USAAF distributed flashy pamphlets, touting a patriotic call to adventure: “It’s a He-Man’s job for men that want to serve their country in the air!”

Other nicknames for the would-be pilots either crazy or brave enough to volunteer included “suicide jockeys,” “tow targets,” and “flak bait.”

But with the promise of hazardous duty pay and the rank of staff sergeant that would go to pilots, Tom Warner and other eager recruits signed up, their sights on flying combat gliders. There was just one problem: no gliders had yet been built.

Most aircraft manufacturers at the time were already producing as many powered aircraft as they could under restrictive government contracts. Eventually, the Waco Aircraft Company (pronounced “wocko”) of Troy, Indiana, won the bid to design and help build America’s first combat glider, the CG-4A.

Waco joined 15 other companies (including the Ford Motor Company) and subcontractors to fill the urgent demand. With a wingspan of 84 feet and a fuselage 48 feet long, the CG-4A was constructed primarily of honeycombed plywood, steel tubing, and canvas fabric. Cargo typically consisted of two pilots and up to 13 troops or a combination of heavy equipment such as a Jeep or 75mm howitzer.

Two pilots sat in the plexiglass nose, which opened upward on a hinge to facilitate loading and unloading. Frequently, however, landings were so rough that cargo had to be cut out of the damaged aircraft with an axe.

Additionally, the locking device holding the nose in the upright position sometimes failed before the pilots could climb back out of the nose, keeping them strapped to their seats and staring straight up into the sky.

Another unpleasant feature of the CG-4A was deafening noise. CBS war correspondent Walter Cronkite experienced this firsthand as a young reporter covering the Battle of the Ardennes: “Riding in those Waco gliders was like attending a rock concert while locked in the bass drum … with enough decibels to promise permanent deafness. I’ll tell you straight out: If you’ve got to go into combat, don’t go by glider. Walk, crawl, parachute, swim, float—anything. But don’t go by glider! This comes from someone who did it––once.”

Early use of the CG-4A in combat during the 1943 invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky) had produced alarmingly high casualties with several gliders crashing into the Mediterranean Sea or into other gliders. Adding the element of enemy gunfire only increased the steep learning curve for the newly arrived pilots. One such lesson was using an extra slab of metal or flak jacket as a seat cushion to avoid becoming a eunuch.

Tom W. Mayer, retired professor, writer, and aviation expert, had this to say about the piloting hazards they endured: “With minimal training, a glider pilot had to be pretty good or he’d screw up the tow plane, too. If the glider climbed too much before the gooney bird was up and flying, the gooney bird could get tipped onto its nose at 80-plus mph and both engines at full power.

“If the glider pilot stayed too low, he was in beaucoup turbulence from prop wash, which made the glider even less controllable than usual and imposed all sorts of unhappy extra stresses on the rope and fuselage.”

Perhaps more aware of their tenuous mortality, glider pilots were regarded as some of the most rebellious soldiers in the Army with little regard for rules and regulations. They were seen as misfits or washouts from other flight programs; many of them were too old or had less than perfect eyesight—or perhaps were just “adrenaline junkies” looking to push the envelope.

In an effort to boost morale, General Arnold announced in late 1943 that all glider pilots completing the program would be upgraded to the rank of flight officer and addressed by the elevated title of “Mister.” The promotion affected little change. With a devil may care reputation, glider pilots refused to assimilate with other flight officers—or even look like them.

Favoring a knit wool cap, old leather flight jacket, and overall casual appearance, they were often mistaken for ground crews and other servicemen. The cavalier group also held the distinction of not being bound to any unit once their mission was completed.

Power pilots regarded them with contempt. Airborne infantry resented riding with them, which they voiced in their very own anthem (sung to the tune of “The Daring Young Man in the Flying Trapeze”):

Once I was Infantry,

but now I’m a dope.

Riding in gliders,

attached to a rope,

Safety in landing is only a hope.

And the pay is exactly the same!

As the Allies prepared for the Normandy invasion (Operation Overlord), Tom Warner earned his coveted silver “G” wings at South Plains Army Air Field in Lubbock, Texas (see WWII Quarterly, Fall 2015) and cleared for duty. More advanced training followed at Laurinburg–Maxton Army Air Base, North Carolina, causing him to miss out on Operation Overlord —a battle that saw extensive use of the CG-4A and continued high glider pilot casualties.

On September 6, 1944, Warner finally shipped out aboard the USS West Point as part of a large influx of replacement pilots. After disembarking in Liverpool, he was assigned to the 441st Troop Carrier Group/99th Squadron and reported to its home base at RAF Langar near the town of Nottingham.

The excitement of stepping on foreign soil for the first time—and in the land of Robin Hood no less—was quickly diminished by the stark reality of war. Only four days after arriving in the European Theater, Warner experienced his first taste of combat in Operation Market Garden over northern Holland.

With the Germans on the run, Montgomery’s ambitious plan hinged on capturing a series of bridges and outflanking the defenses of the Siegfried Line, providing a clear path into the vital industrial Ruhr Valley. The Nazis, however, weren’t done yet.

Additionally, several logistical blunders by the Allies—largely at the expense of paratroopers and glider-borne forces—led to catastrophic results. The operation was supposed to have ended the war in Europe by Christmas but instead resulted in bitter disappointment and was later immortalized in print and film with the aptly named A Bridge Too Far. The Allies now counted on Operation Varsity to finish the job.

Plans for the Rhine crossing began shortly before the Battle of Bulge in November 1944. The formidable river, with its swift currents and high banks, served as the last major natural obstacle to an advance into Germany. Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower was determined to avoid the same problems that had plagued Market Garden but reluctantly agreed to another complex joint ground and airborne assault near the town of Wesel.

Spearheaded by Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, Operation Plunder/Varsity would ultimately involve over a million soldiers, consisting of 30 divisions from the British Second Army under Lt. Gen. Miles C. Dempsey, the Canadian First Army under General Harry Crerer, and the American Ninth Army under Lt. Gen. William Simpson. Air support would be provided by the newly created First Allied Airborne Army (FAAA), commanded by Lt. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton.

Before facing the enemy, however, rampant infighting at high command threatened to derail the entire offensive. Brereton had assigned his deputy, British Maj. Gen. Richard N. Gale, as the chief planner and commander of the airborne operation—a move Montgomery vehemently rejected. Gale was then replaced by the more experienced Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, commander of the U.S. XVIII Airborne Corps.

Ridgway, however, had loftier ambitions; privately, he had expressed desire to take command of an army and wanted no part of an unconventional mission to tarnish his reputation. He also despised Dempsey, blaming him for the disaster of Market Garden.

Eisenhower, who had played football at West Point, now found himself in the unfamiliar role of referee. Eventually, Ridgway acquiesced and begrudgingly accepted the command.

Eisenhower had also grown increasingly frustrated with Montgomery, who resented the American’s authority as his superior officer. Whether deserved or not, Monty’s overly meticulous reputation didn’t help matters—nor did his typical refusal to engage the enemy unless ensured a vast superiority in troops. (After the war, a dry Martini using a 15:1 gin to vermouth borrowed the namesake “Montgomery,” which, according to his critics, replicated the same ratio Monty preferred to outnumber his enemy in battle.)

The men of the 441st TCG/99th Squadron bivouacked over the winter of 1944/45 at an airbase in Dreux, France, while awaiting their next mission. They faced the usual trappings associated with military life—lousy food, cramped quarters, drills, boredom, etc., and passed the time playing cards or listening to the popular “Axis Sally” (aka “The Berlin Bitch”) propaganda radio program.

At 31, Tom Warner was older than most of the other glider pilots. Growing up in Arkansas, he had been a champion athlete, breaking the state record in the hurdles. Like all the Warner boys, he was a skilled outdoorsman and crack shot—traits that served him well later in life.

His easygoing demeanor and Southern charm provided a welcomed balance to the odd assortment of personalities and backgrounds in his squadron; battle-tested Louis Canaiy had seen the most combat among the group, including the debacle in Sicily where only 12 of the 147 gliders landed on target and 69 crashed into the drink; Don Manke, soft- spoken and educated, studied geology and paleontology at the University of Wisconsin before enlisting in the Army Air Corps.

Another, Leonard Hulet, hailed from a small mining town in rural Utah and had barely survived D-Day when his glider crashed in a field littered with Rommel’s asparagus—long wooden poles dug into the ground and attached to explosives.

And then there was “Goldie.”

At the ripe age of 21, Curtis J. Goldman landed in the war possessed with unbridled energy and an equal appetite for hijinks. The brash, cocky Texan had been nearly court-martialed on multiple occasions for infractions ranging from willful disobedience to irresponsible flying of a military aircraft. Once, while flying in a training exercise near London for top brass, Goldman grew restless and decided to step outside the glider for a better view of the parade grounds below.

Suddenly, a gust of air knocked him off balance, and Goldman found himself clinging to a wing strut upside down. Miraculously, he was pulled to safety by paratroopers on board only moments before landing. Afterward, Goldie merely shrugged off the incident and continued about in search of his next bit of mischief.

The 99th Squadron periodically volunteered to assist C-47 crews by flying co-pilot on resupply and evacuation assignments. Close proximity to Paris also provided a highly welcomed diversion from the war—especially for glider pilots whose perilous fate remained uncertain. After Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army liberated Paris in late August 1944, the City of Light shone once again, offering a vast array of entertainment and vice for the conquering heroes.

While the Champs Elysees and Eiffel Tower made for great snapshots, those looking for more risqué entertainment found it in the raunchier districts of Montmartre and its notorious Pigalle area (dubbed “Pig Alley” by GIs). The inflation-ravaged French capital saw champagne flow day and night in makeshift casinos and popular nightclubs such as Club Mayol and the infamous Moulin Rouge.

Horizontal refreshment was also easily procured at the plentiful Maisons de Rendezvous, where the four Cs of wartime rations—cigarettes, chocolate, coca-cola, and chewing gum—were often preferred over hard currency. Not surprisingly, a pack of Lucky Strikes provided more than just “toasted” tobacco pleasure for a soldier on a three-day furlough inside these Gaullic dens of sin.

By March 1945, details for Varsity began to solidify despite a number of last-minute changes directly affecting glider-borne troops. Montgomery’s insistence on a daytime vertical envelopment would once again put gliders and paratroopers in an exceedingly vulnerable position from ground fire without the cover of darkness.

D-day for Varsity was set for March 24 on the heels of Operation Plunder and called for three airborne divisions: Maj. Gen. Eric Bol’s British 6th “Red Devils” and two American divisions, Maj. Gen. Elbridge G. Chapman’s 13th Airborne and Maj. Gen. William (Bud) Miley’s 17th Airborne (“Thunder from Heaven”).

The Americans were assigned the southern portion of the drop and landing zones with the British taking the northern sector in an area six miles east of the Rhine. Varsity would also become the first operation in which gliders landed prior to paratroopers securing the area; the plan called for the use of double-towed gliders—a first in the ETO (earlier results in Burma had been mixed).

Not surprisingly, Ridgway remained leery and became further enraged upon learning Allied resources could only accommodate two airborne divisions: the 6th British and the American 17th. Both divisions would drop east of Wesel and were tasked with disrupting enemy defenses to aid the advance of Dempsey’s Second Army. Objectives included seizing the well-fortified Diersfordter Forest, the town of Hamminkeln, and several bridges over the smaller but strategically vital Issel River.

Meanwhile, Montgomery’s ego suffered another blow when elements of General Courtney Hodge’s First Army captured the lightly defended Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen, becoming the first invading force to cross the Rhine since Napoleon. A few weeks later, Patton, Monty’s arch-rival, achieved the same feat near Oppenheim with only one division.

Expectedly, “Old Blood and Guts” couldn’t resist gloating: “I want the world to know that Third Army made it before Monty starts across.” The fiery British field marshal was livid—and now more determined than ever to strike a death blow into the heart of the Ruhr and arrive first in Berlin.

Unlike the invasion of Normandy, minimal effort was being made by the Allies to create a subterfuge. The Germans were undoubtedly aware of increased activity west of the Rhine and began digging in. Even Axis Sally joined the fight, taunting the invaders on her radio broadcast in the days leading up to the battle. “We know you are coming, 17th Airborne Division, you will not need parachutes—you can walk down on the flak.”

Under the command of General Günther Blumentritt, the battle-hardened Wehrmacht positioned 10 divisions along the Rhine. The 1st Parachute Army anchored the defense, placing the 2nd Parachute Corps to the north, 86th Corps in the center, and 63rd Corps in the south. Blumentritt’s line was further bolstered by the late arrival of the XLVII Panzer Corps that included the menacing 15th Panzergrenadier Division and the 116th Windhund (Greyhound) Division.

Prior to the operation, British engineers began laying a 60-mile-long smokescreen outside the town of Emmerich, which not only alerted the Germans of an imminent attack but later caused significant visibility problems for Allied troops.

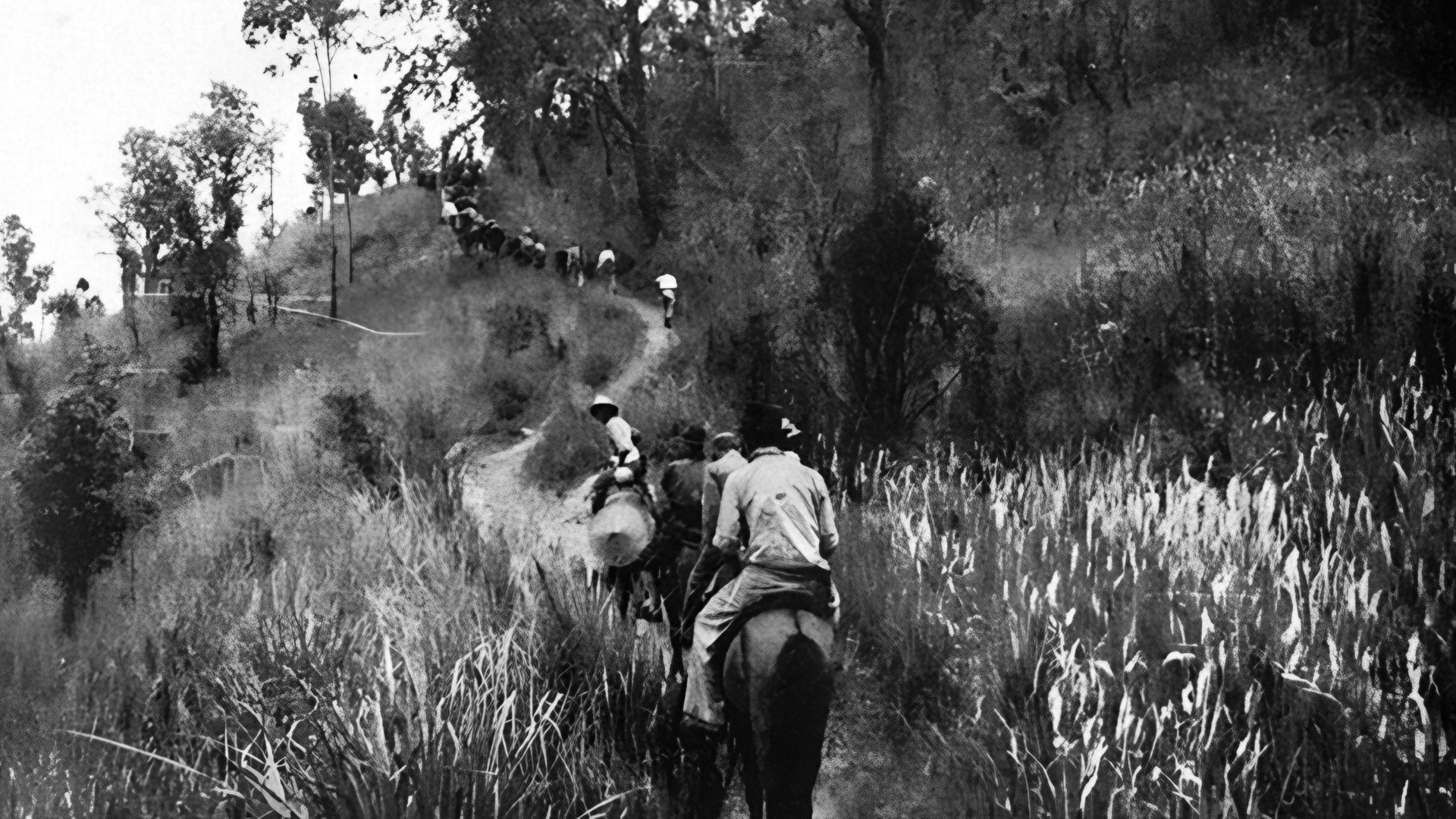

At 9 pm, Operation Plunder was initiated by the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division led by the vaunted 7th Battalion Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) near Rees.

Heeding their Latin motto, Nemo me impune lacessit (“No one provokes me with impunity”), the pugnacious Scots charged over the Rhine in the shadow of night. The bulk of the amphibious forces commenced shortly after, signaling the coded message, “Two if by sea,” to Airborne HQ. Operation Varsity had begun.

The glider pilots awakened that morning to a hearty meal of steak and eggs; many wondered if it would be their last. At 6 amreligious services were held and well attended. The pilots then loaded into a convoy of trucks and assembled in the back of a long flight line.

Warner, along with his co-pilot Louis Canaiy, boarded their chalk-marked #11 glider in one of the last serials and waited for a tug plane to take them to Germany. Their cargo included a jeep along with personnel of the 224th Airborne Medical Company, transporting critically needed medical equipment and supplies.

At RAF bases across the English Channel, the British Glider Regiment, equipped with their trademark maroon berets, prepared to join their American counterparts. Like the CG-4A, the British Horsa and Hamilcar gliders would be easy targets for German antiaircraft crews used to targeting high-speed, well-armed fighters and bombers.

In comparison, the lumbering gliders resembled a carnival shooting gallery—and the mammoth Hamilcar looking more like the Hindenburg. Named for the famed Carthaginian general, the Hamilcar was considerably larger than all other Allied gliders, featuring a wingspan of 110 feet, a length of 68 feet, and a capacity to transport a load of 17,600 pounds, including an M22 Light Locust tank.

Learning from the glider-borne landings at Normandy and Arnhem in 1944, the Germans had also discovered tracer bullets could effectively set aflame the bulky gliders long before they reached the ground. The well-entrenched gunners eagerly awaited them.

The first planes carrying the 17th Airborne departed at 7:17 am, with the last serials getting aloft two hours later. The lift included 9,387 American paratroopers and glider-borne soldiers carried aboard 72 C-46s, 836 C-47s, and 906 CG-4As. Combined with a British force of 1,228 tow aircraft and gliders carrying more than 8,000 soldiers, the massive armada stretched over 200 miles and took 37 minutes to pass at any given point, creating a thundering display of Allied might.

The two divisions converged 100 miles from the target at a designated rendezvous point over Brussels; escort fighters from the RAF and U.S. Ninth Air Force providing additional muscle with squadrons of Spitfires, Hawker Typhoons, P-51s, and P-47s.

The enormous formation also presented unforeseen problems; the buildup of air traffic created a stairstep effect, forcing several gliders to a precariously high release altitude of 2,500 feet, thus giving German ground crews ample time to shoot at the plodding targets.

Just before 10 am, and slightly ahead of schedule, the 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) led the Americans’ drop across the Rhine. Despite the calm weather, the drop zones remained blanketed with dense haze caused by the smoke screen covering the river crossings. Although the Americans were forced to land nearly two miles away from their drop zone, they encountered relatively light antiaircraft fire.

The British 6th Airlanding Brigade wasn’t as fortunate. Under Brigadier Hugh Bellamy, the 6th AB carried the first gliders into battle and was immediately blasted by flak, tanks, and mortars from the thickly forested Diersfordter.

In nearby farmhouses, snipers picked off paratroopers seemingly at will. In the confusion, several pilots became lost and landed in the wrong zones or crashed into trees and other gliders, creating a salvage yard of tails, rudders, and wings strewn about the LZ.

The 194th Glider Infantry Regiment under Colonel James Pierce followed in doubled tows over DZ S amid continued poor visibility and concentrated ground fire. They also encountered the alarming sight of Allied tugs riddled with bullets (and several on fire) returning home base.

More carnage ensued. A German 88mm shell tore apart a Hamilcar loaded with a M22 tank over the Rhine, scattering its equipment and killing all on board.

On LZ P, Staff Sgt. Desmond Page transported troopers of the 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Battalion (2nd Ox & Bucks) and later recalled the chaos: “The flak was murderous and almost immediately the leading glider was literally blown to pieces. The flight cabin, men and bits of fuselage fell away in front of us and most of the undercarriage hit our tail plane. No one was going to survive that.”

Meanwhile, on the ground lifeless paratroopers dangled from tall oak trees in the Diersfordter, where burial squads with pruning saws and ladders would later need two days to cut down all the dead. Adding to the surreal nightmare, a cacophony of hunting horns blared loudly from British commanders, using different calls to muster their troops—all contributing to a proper “buggers muddle.”

Eventually, the British recovered and secured most of their hard-fought objectives including the town of Hamminkeln. They also benefited from the American 513th PIR, which had been dropped by mistake in their sector. The Yank paratroopers included legendary war photographer Robert Capa, who bolstered his already daring reputation by snapping the most iconic photos of the battle while on assignment for Life magazine.

“The 40 seconds to earth were like hours on my grandfather clock,” Capa recalled, “and I had plenty of time to unstrap my cameras. On the ground I kept clicking my shutter. We lay flat on the earth and no one wanted to get up. The first fear was over and we were all reluctant to begin the second.”

With arms aching after spending 31/2hours tethered to a 350-foot nylon umbilical cord, Tom Warner finally cut his glider loose at around 12:30. Bursts of flak continued darkening the sky around the airhead while chaos reigned underneath them. Warner nodded to his co-pilot Canaiy and began descending toward the smoke-covered landing zone below.

LZ N was the most northerly of the two American landing zones and bordered the northwest side of the still hot Diersfordter. A checkerboard pattern of fields and meadows filled the rectangular-shaped area along with several other obstacles, including farmhouses, railroad tracks, and the main power line strung on 100-foot pylons. The zone served as a buffer between the American and British sectors, providing a clearing medical station site for the expected flood of casualties.

By this stage, most paratroopers and gliders were on the ground fighting for survival. Bodies rapidly piled up, and the doctors and medics did what they could. As precious seconds ticked away, Warner could now see the ground at 300 feet; unfortunately, the enemy could now see him. Pilots continued smashing into other gliders, trees, and poles as Warner desperately searched for a small clearing in the crowded LZ.

An Army issue .45-caliber M3 submachine gun, known as the “grease gun,” rested under his seat ready to join the fray. He also carried a .45-caliber pistol for his aviator to infantry transition once on the ground.

With time running out, executing a standard 360-degree flight path was out of the question. After releasing from its tow, a pilot had only a few minutes at best to put the glider down or risk stalling out. Enemy guns, dense smoke, and vomit-inducing turbulence didn’t help. Out of options, Warner plunged into a dive to hasten the glide path and elude ground fire.

The result produced a fast, rough landing intact on a field littered with mangled wreckage, destroyed livestock, and dead soldiers. Canaiy and medics from the 224th quickly exited through the side door, dodging a barrage of gunfire from all directions. The jeep and supplies would have to wait.

Warner grabbed his M3 and finished busting out the plexiglass panel. He kept his head down and relied on his runner’s legs, sprinting like mad with bullets pinging overhead. He eventually found refuge in a small ditch next to a tree-lined road and waited for the bedlam to subside.

At 2:58 pm, roughly five hours after the first airborne troops landed, patrols from the British 1st Commando Brigade reached elements of the 17th Airborne, establishing the fastest linkup of ground and airborne forces in the war. Warner met up with members of his squadron to survey the horrific destruction.

As nightfall approached, scuttlebutt of missing pilots turned into hard, cold facts. Five men from the 441st/99th had been killed, including Flight Officer Hulet. Ironically, Hulet wasn’t even supposed to take part in the mission but had volunteered at the last minute when a married replacement pilot requested not to fly. Goldman and Manke had flown together and managed to survive, despite taking heavy ground fire.

Upon landing, however, they suffered the misfortune of running over a dead paratrooper. The experience would haunt the young Texan for the rest of his life. “It was a sickening sound when one of the wheels of our glider ran over his body,” he said. “As we got the glider stopped, we were already aware that intense fighting was happening all over the area. Grenades and mortars were exploding. Germans and paratroopers were mixed up like mush.”

The British witnessed similar heartbreak in their sector. Major Jack Watson of the 13th Parachute Battalion recalled a particularly ghastly incident. “The saddest thing I saw was when we were moving toward our objective. There were these glider pilots, sitting in their cockpits, having been roasted alive after their gliders had caught fire … a lot of people were lost like that.”

A trickle of German prisoners soon turned into a deluge. Eventually, airborne forces captured more than 3,500 men, with thousands more lying dead or wounded in surrounding fields. Astounding bravery resulted in a Victoria Cross, two Medals of Honor, and the only Conspicuous Gallantry Medal issued in the war. Varsity also produced an extraordinary feat of heroism by gliders pilots in what became known as “the Battle of Burp-Gun Corner.”

Three weeks prior to the operation, the 194th Glider Infantry Regiment had been one company short and needed volunteers. A new unit would consist of only glider pilots to assemble after landing in their designated zones. The CO of the 435th Troop Carrier Group, Major Charles O. Gordon, accepted the assignment and transformed his four squadrons into the 435th Provisional Glider Pilot Company.

After landing in LZ S with the troops and equipment from the 194th Glider Infantry Regiment and the 681st Glider Field Artillery Battalion, the company came under heavy ground fire before assembling at its assigned area just north of Wesel at the crossroads of Holzweg and Hessenweg. In nearby farmhouses, enemy soldiers relentlessly fired their MP-40 submachine guns—nicknamed “burp guns” for their rapid rate of fire. The glider pilots fended off the attack, holding their own in a series of firefights, but the worst was yet to come.

Around midnight, a force of approximately 200 German infantry, retreating ahead of British forces, arrived supported by a tank, self-propelled artillery, and two 20mm flak guns. They attempted to overrun the 435th’s line, but Flight Officers Chester Deshurley and Albert Hurley stood their ground, firing their machine guns along with Flight Officer Robert Campbell, armed with only a tommy gun, until the tank came within 15 yards of them. What followed is the stuff of pure legend.

Flight Officer Elbert Jella picked up a bazooka—the first and only time he fired one in combat—and struck a bulls-eye, crippling the tank and causing it to reverse and destroy one of its flak guns. By morning, a large number of enemy troops had been killed and several hundred prisoners were captured.

The fight was dubbed “the Battle of Burp-Gun Corner” by a journalist from the Stars and Stripes. Major Gordon requested that all the men of the 435th Provisional Glider Pilot Company be given due recognition. But the war soon ended and the order was lost and eventually forgotten. In 1996, however, after exhaustive work, all the men of the 435th (most posthumously) received the Bronze Star, and Campbell, Hurley, Deshurley, and Jella were awarded the Silver Star.

Fortunately for the Allies, valuable lessons had been learned from Market Garden, the earlier botched invasion of Holland. Montgomery’s swift crossing of the Rhine had been an overwhelming success, capturing more than 30,000 soldiers and sending the enemy into full retreat. By March 27, 12 Allied bridges spanned the Rhine, opening the northern route into the industrial heart of Germany.

Varsity was also seen as a spectacular triumph. Dropping both airborne divisions simultaneously had overwhelmed enemy defenses. Two months later Germany surrendered. Eisenhower called Operation Varsity “the most successful airborne operation carried out to date.”

While tactically successful, the cost was dreadfully high. A total of 1,111 men had been killed during the single worst day of the war for Allied airborne troops. American gilder pilots were hit the hardest, with 79 killed, 240 wounded, and 31 missing. British losses were equally devastating. According to the British Ministry of Information, nearly a quarter of British glider pilots were casualties, and a staggering 79 percent of its gliders had been damaged by enemy fire.

Over the years, many historians have questioned the necessity of Varsity and accused Montgomery of typical grand-standing and overkill. Given the relatively weak resistance encountered during the river crossing, it is a fair assumption that the Germans’ defense centered on defeating the much smaller and manageable airborne forces.

For those keeping score, Operation Plunder’s 30 divisions to Varsity’s two presents a fairly lopsided tilt. It is also worth noting that Allied bombers destroyed 97 percent of Wesel a week prior to the operation during the “softening” of the area, including the use of 10 22,000-pound earthquake bombs (“two-ton tessies”).

In his wartime memoir A Soldier’s Story, General Omar Bradley asserted that if Montgomery had crossed the Rhine on the run as Hodges and Patton did (sans air support) or allowed Simpson’s Ninth Army to proceed in a similar manner, there would have been no need for Varsity. Curiously, however, Ridgway would later claim that Varsity was the decisive factor in Montgomery’s Rhine crossing. And so goes the debate.

By the time the next war rolled around, combat gliders had become obsolete, replaced by the helicopter. Like Civil War-era balloons or Hannibal’s battle elephants, the CG-4A joined other relegated weapons of war with colorful anecdotes and historical footnotes. Glider pilots who survived the war returned home and went about their lives.

Louis Canaiy moved to Colorado and went into the hospitality business, building and operating the Lake Estes Motor Inn and serving on the state tourism board. Don Manke returned to college in Wisconsin and was employed as an engineer with Texaco for many years. After raising hell throughout the war, Curtis Goldman fittingly enrolled in seminary school and began a long career as a Baptist minister.

As for Tom Warner, the Arkansas country boy pointed his compass west in search of a new adventure. For his war efforts, he had received a Distinguished Unit Citation, Silver Air Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster, four Bronze Service Stars and a Bronze Service arrowhead, and the Order of William Orange Lanyard.

But, like most men of his generation, Warner rarely discussed the war. He didn’t consider himself a hero but rather just another soldier who did his job and was lucky to be alive. He also never set foot in another aircraft. Ever.

Long before the term PTSD was introduced, returning soldiers simply coped the best they could. To ease his pain, Warner drank heavily. Random images from his scrapbook reveal a labyrinth of bittersweet memories: flying over the Rhine; mangled gliders; dead soldiers lying in a field; war buddies huddled around a captured Nazi flag.

Eventually, he settled in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he married a young gal he had met while stationed at a glider training facility. He successfully transitioned into civilian life and became an executive at First Bank of New Mexico. In 1971 his nerves would be tested again during an attempted bank heist in which a gun was pointed at his head. He remained calm throughout the ordeal and was later promoted to vice president. The bad guys went to jail.

Warner spent his retirement playing golf and enjoying quiet evenings with my great-aunt before passing away in 1999. According to the National World War Glider Pilots Association, fewer than 200 of the original 6,000 glider pilots are still alive today, but their spirit remains strong—reminding us all that the “G” on their wings did indeed stand for “guts.”

My father, Don D. Fritz, FO, was a glider pilot in the Market and Varsity operations. He survived the war; but, was killed spaying crops with a piper cub in 1949. In one of his mission reports (handwritten), in the suggestion portion he requested glider pilots be issued M1 Garrands, instead of carbines and Tommy guns. He evidently wanted to fire at enemy from a greater distance.

In the late 90s, the AF Academy cadet Instructor Pilots in the soaring program were presented replica WW II glider pilot wings when they qualified as IPs.