By Daniel Murphy

Late in the evening of July 3, 1863, Major General James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart was summoned to the headquarters of Robert E. Lee. Three days of combat had inflicted heavy losses on Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, and Lee needed to discuss his retreat from Gettysburg with the chief of his cavalry. Lee selected two routes—his ambulance train would head west with a heavy escort of cavalry and artillery, cross South Mountain via Cashtown Pass, and turn south for Williamsport, Maryland, on the Potomac River. Lee’s main army and the vital grains and livestock secured from the invasion, would head south to Hagerstown, Maryland, crossing South Mountain at Monterey Pass. At Hagerstown, his troops and trains would depart for either the established ford at Williamsport, or a pontoon bridge waiting downstream at Falling Waters. The length of the Confederate trains was staggering—with captured stores and livestock the quartermaster train alone stretched 40 miles, and was given a 15-hour head start for the retreat. Lee needed Stuart to screen his eastern flank and secure the multiple passes over South Mountain. If Stuart could hold his flank, Lee’s troops and trains might make it back to Virginia.

A veteran of Stuart’s brigades, who spotted Rebel wagons moving south early the next morning remarked, “That looks like a mouse,” meaning such a sight never followed a success. These were apt words indeed—Lee’s army was turning on its heel.

On the following morning, July 4, General George Meade received word that Confederate wagons were retreating from Gettysburg—proof positive his Army of the Potomac had won a major victory. Conventional military wisdom called for launching an all-out pursuit to destroy the retreating army. But the reality was that, though Meade’s army had indeed won a clear and substantial victory, three days of combat at Gettysburg had inflicted nearly 30 percent casualties on Meade’s troops and his soldiers needed refitting and ammunition. In addition he’d lost 1,500 artillery horses and nearly 400 mules. The horses that survived had subsisted on little more than grass the prior week, and this, coupled with the recent march up from Virginia, left many mounts depleted and in need of a rest and proper feed. A case in point was General John Buford’s 1st Cavalry Division, two-thirds of his horses were in such sad shape that on the second day of the battle they were rotated out of the lines. In short, the Army of the Potomac lacked the ready horse power required to go after Lee’s forces.

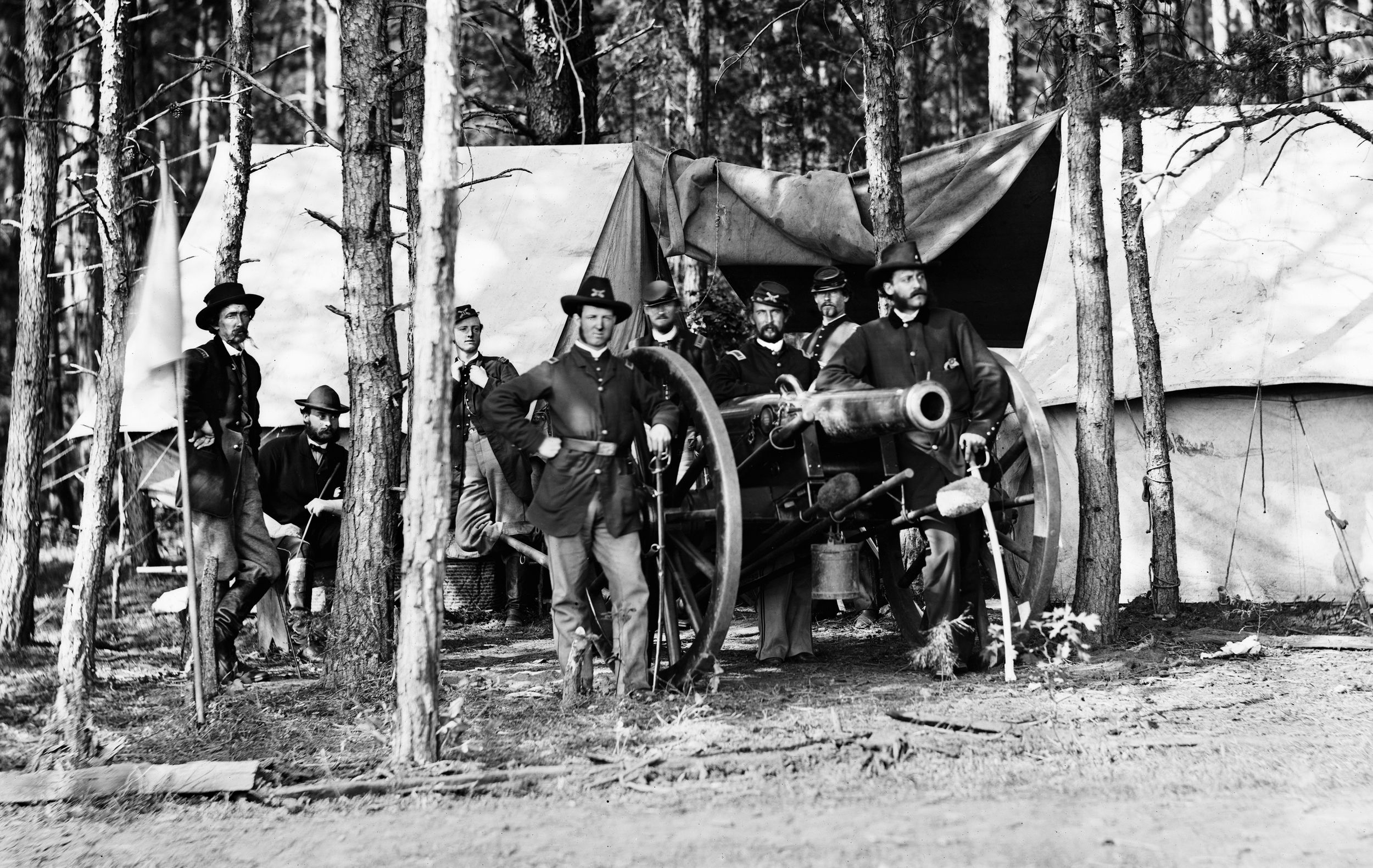

Instead, Meade sent his available cavalry forward to scout Lee’s retreat and cut his trains. Judson Kilpatrick’s 3rd Division left in a rainstorm on July 4 to strike Confederate wagons rumored to be crossing Monterey Pass. Kilpatrick, 27, was impulsive, acerbic, and a natural brawler. He drove his men through the heavy rain, and captured 300 wagons and 1,000 prisoners in a galling night attack at the mountain pass. Kilpatrick collected his spoils, and rather than turn back for Gettysburg, he moved south for Smithsburg, Maryland, long before the sun came up.

Remarkably, the remainder of the Confederate train went unnoticed by Kilpatrick in the pitch-dark night, and the vital wagon train soon resumed its course for Hagerstown.

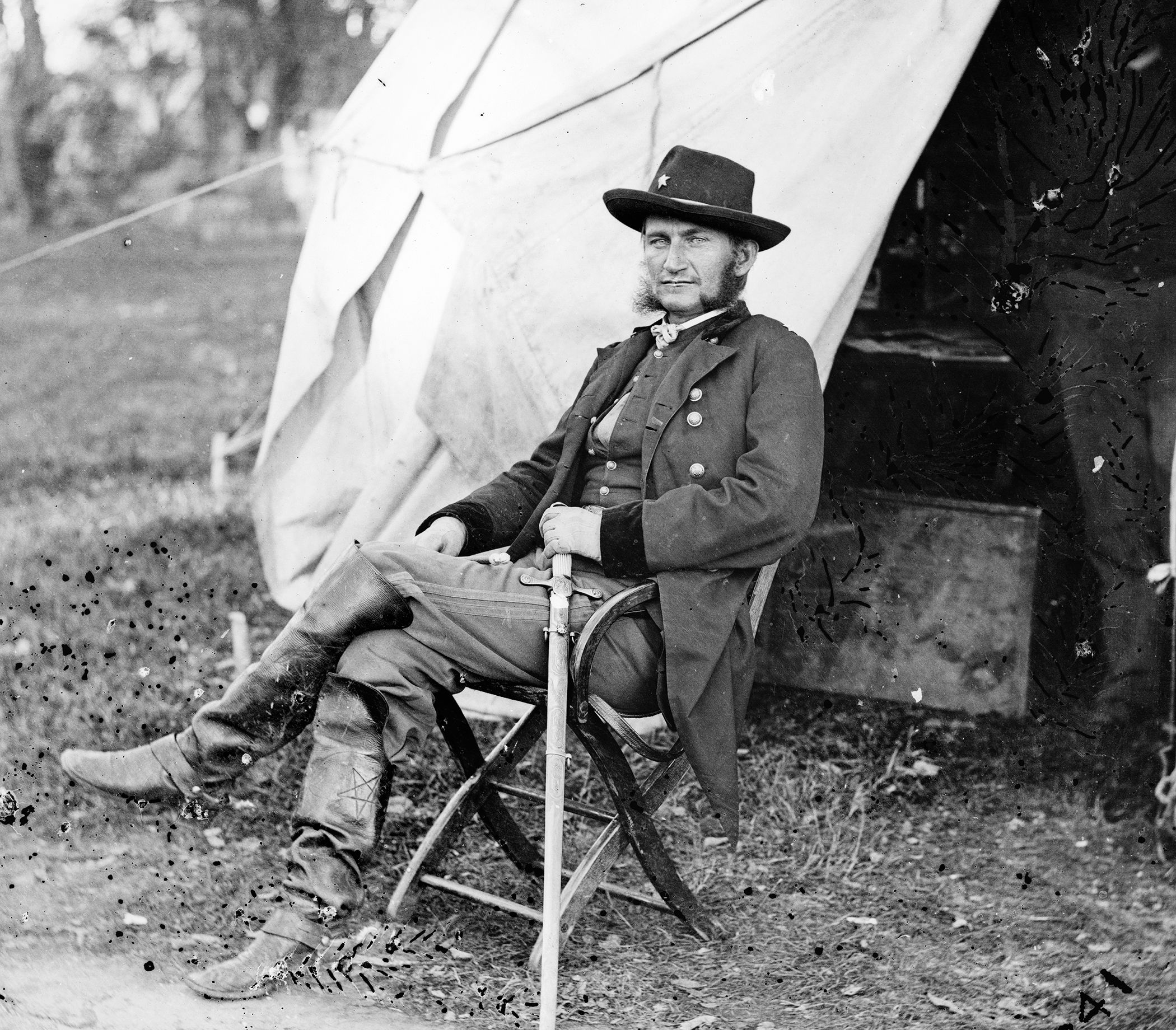

Stuart also spent the night of July 4 riding through the rain, along with the brigades of Colonels John Chambliss and Milton Ferguson. Stuart’s column arrived at Emmitsburg, Maryland, the next morning, and found it occupied by Federal troops. Stuart and his troopers made quick work of the Federals and captured the town along with some 60 Union soldiers.

Stuart then learned of Kilpatrick’s attack at Monterey Pass, and recognized his planned course over the mountains was now blocked. After questioning his prisoners, and sketching a series of local maps, Stuart crisscrossed his way past Wesley Merritt’s Federal cavalry, crossed over South Mountain, and came out above Smithsburg, via Raven Rock Pass. The town of Smithsburg controlled two crucial passes through South Mountain, and Kilpatrick’s 3rd Division now sat across the key township in a broad arc from north to east. Launching a pair of quick attacks, Stuart gained the ground above the town and ordered a horse battery pulled onto a summit overlooking the enemy position below. Rebel guns soon forced Kilpatrick to retreat to the south, and, after ensuring Kilpatrick’s departure, Stuart moved northwest, to better cover the course of Lee’s retreat through Hagerstown.

Bivouacking that evening in Leitersburg, Stuart linked up with the brigades of Beverly Robertson and Grumble Jones, increasing his force to four diminished, but willing, brigades. It had been a long and successful day for Stuart and his horsemen. That night he learned Lee’s trains were making steady progress, having already arrived at Williamsport on the Potomac. That was the good news. The bad news was that a massive traffic jam of wagons and wounded Confederates was building on the Potomac’s north bank. High water from recent rains meant the wagons had to be pulled across with a small cable ferry in a time-consuming process. Worse still, a Union cavalry foray had destroyed the pontoon bridge downstream at Falling Waters, exponentially increasing the time it would take the Confederates to cross the river—granting Meade’s Federal forces even more time to sweep down and pin Lee’s retreating army against the rising river.

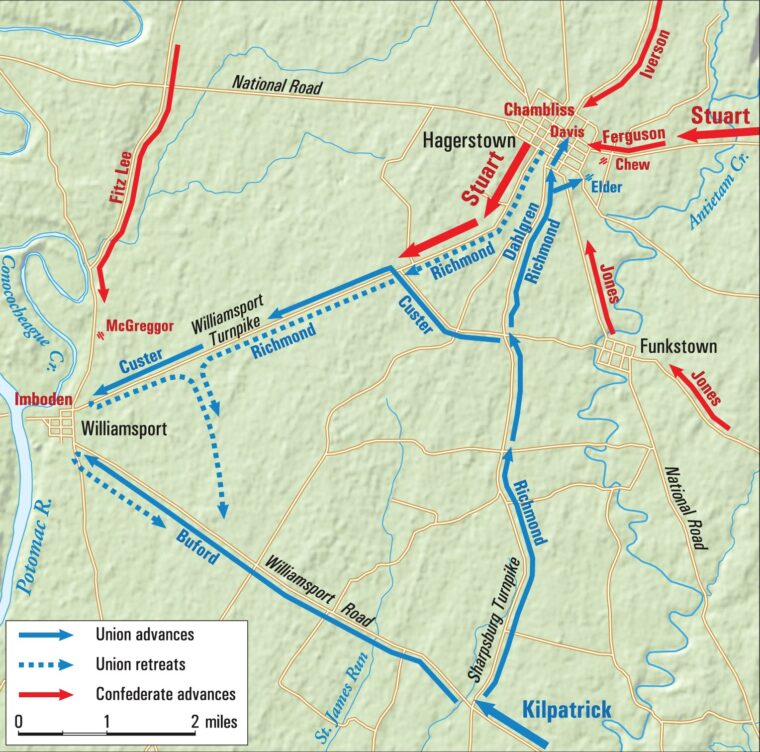

On the morning of July 6, Kilpatrick linked up with Buford near Boonsboro, Maryland. The commanders decided to make a two-pronged attack on the stranded enemy wagons above the Potomac. Buford’s rested 1st Division would strike deep for Williamsport, while Kilpatrick’s 3rd Division would split north, attack Hagerstown, and screen Lee’s main retreat column. With Williamsport isolated from support, Buford stood a good chance of destroying Lee’s wagons, capturing thousands of wounded Confederates, and striking a devastating blow against Lee’s army.

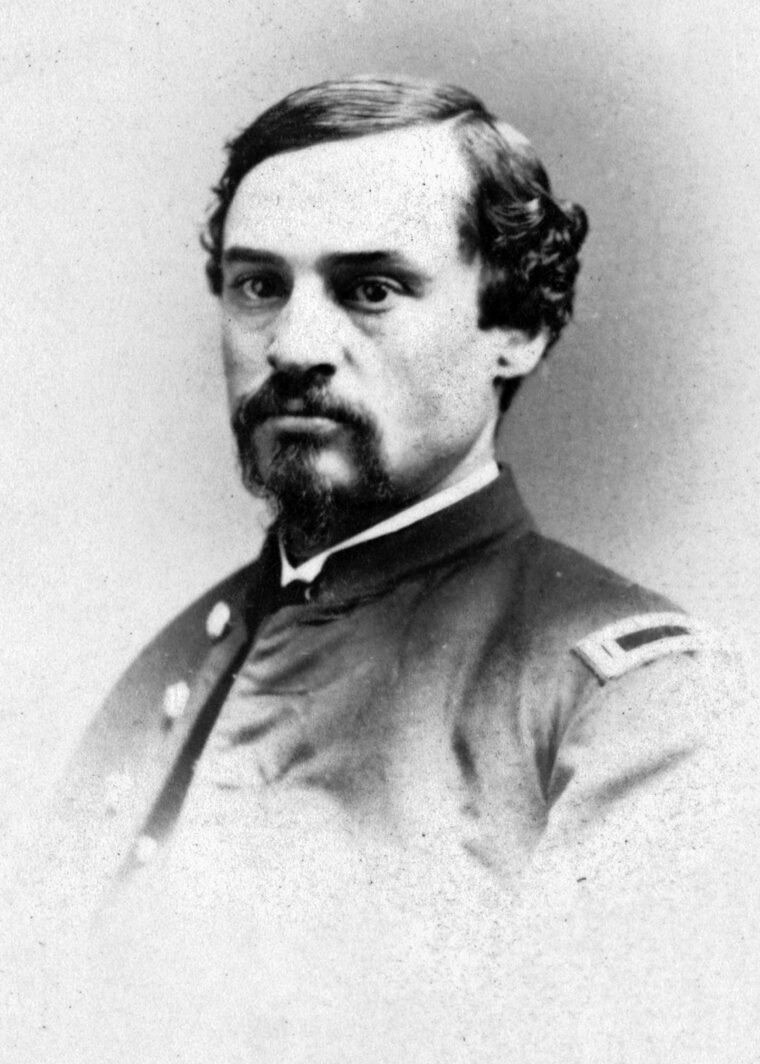

Kilpatrick would divide his own division in half: Custer’s second brigade would hold between Hagerstown and Williamsport, as Kilpatrick’s first brigade, under Colonel Nathaniel Richmond would push into Hagerstown and secure the town center. At the start of the war, Richmond gained a field commission in the Federal 1st Virginia Cavalry (soon to be West Virginia) and proved a quick study. In heavy skirmishing prior to the Battle of 2nd Manassas, he led a plunging saber charge against Confederate infantry. Richmond’s charge drew earning him considerable praise from his commanders and the respect of his men. Hagerstown would be Richmond’s first time leading a brigade, having just taken command upon the death of Elon Farnsworth at Gettysburg.

A courier woke Stuart on July 6 with a note from Lee. The commanding general reported his infantry and trains continued to move through Monterey Pass with little trouble from the enemy. In response, Stuart directed Chambliss and Robertson to march on a direct path to Hagerstown that morning, as Stuart wanted to secure this key point as soon as possible. Jones’s brigade headed south to the next hamlet of Funkstown, with orders to hold there and cover the southeastern approach via the National Road and Boonsboro. Stuart then joined Ferguson’s brigade on their later march for Hagerstown.

Chambliss arrived in Hagerstown in time to see Lee’s wagons passing through the town center on their way to Williamsport. The former commander of the 13th Virginia Cavalry, Chambliss, was a West Point graduate who took over W.H.F. “Rooney” Lee’s brigade after the younger Lee sustained a wound at Brandy Station. He had since proved a capable commander, and all seemed well in Hagerstown until a report arrived mid-day announcing a large force of Federal cavalry closing from the south. Kilpatrick had passed south of Funkstown on his approach and turned north on the Sharpsburg Road, which ran west of Jones’s position, allowing the Federals to gain a hidden approach to Hagerstown. Chambliss sent riders sprinting for Stuart with news of the Federal approach and then ordered Colonel Lucious Davis and his 10th Virginia Cavalry to barricade South Potomac Street below the intersection of Franklin Street. He next ordered pickets from the 9th Virginia and 1st Maryland to support Davis’s barricade, and placed the 13th Virginia and 5th North Carolina up at the Zion Reformed Church to act as a mounted reserve. Lee’s wagons, in the meantime, halted north of town. When Chambliss’s warning reached Stuart, he ordered Ferguson’s brigade to take up a gallop.

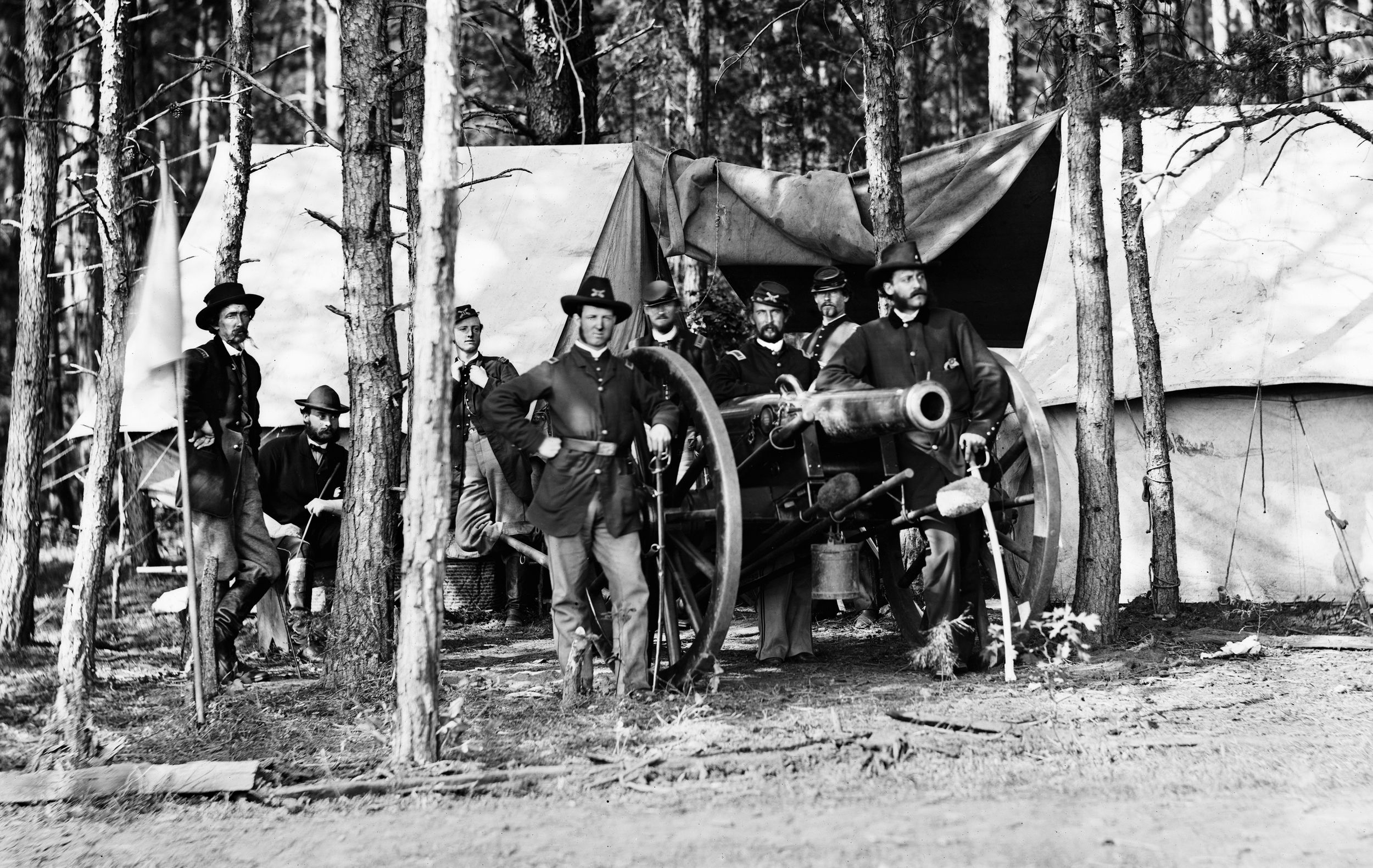

As Richmond’s Federal brigade entered Hagerstown from the south, Ferguson’s Confederate brigade appeared from the east. Turning to meet this threat, Richmond deployed Lieutenant Samuel Elder’s battery near the Female Seminary on the south-east end of town. The Federal fire forced a quick halt in Ferguson’s column, but Jones’s brigade, having doubled back from Funkstown, now arrived, and Captain Chew’s battery soon came into play as both batteries fired through the narrow town streets. “The artillery fire was severe,” recalled a Southern gunner. “[T]he range was short and their ten pound shrapnel whizzed fearfully and exploded all around us.” Ferguson dismounted his sharpshooters and sent them forward to open on Elder’s guns, forcing Elder and his supporting sharpshooters to shift their position. Elder called for more support, and sharpshooters from the 1st West Virginia came up as the battery shifted position and opened yet again, creating a stalemate in this section of the town.

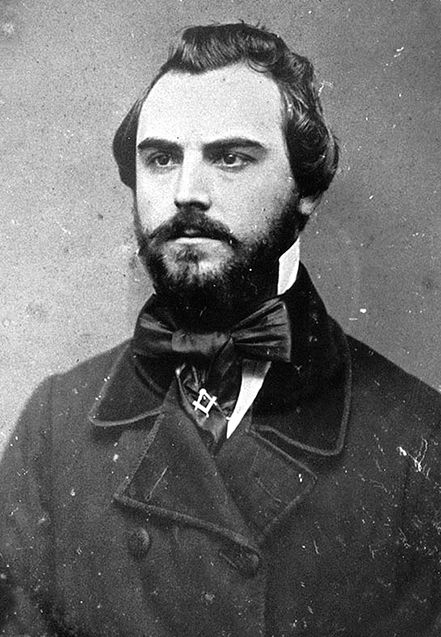

As Richmond turned his attention to the Confederate barricade on South Potomac Street, Captain Ulric Dahlgren arrived and volunteered to join the attack. Ulric, the son of Federal Rear Admiral John Dahlgren, had recently been ranging across the countryside with a handpicked group of troopers, raiding wagons and seizing couriers behind enemy lines like a Federal version of John Mosby. With hard work ahead, Richmond readily accepted Dahlgren’s offer. Dahlgren’s men, plus two squadrons from the 18th Pennsylvania, and one from the 1st West Virginia, would make the attack.

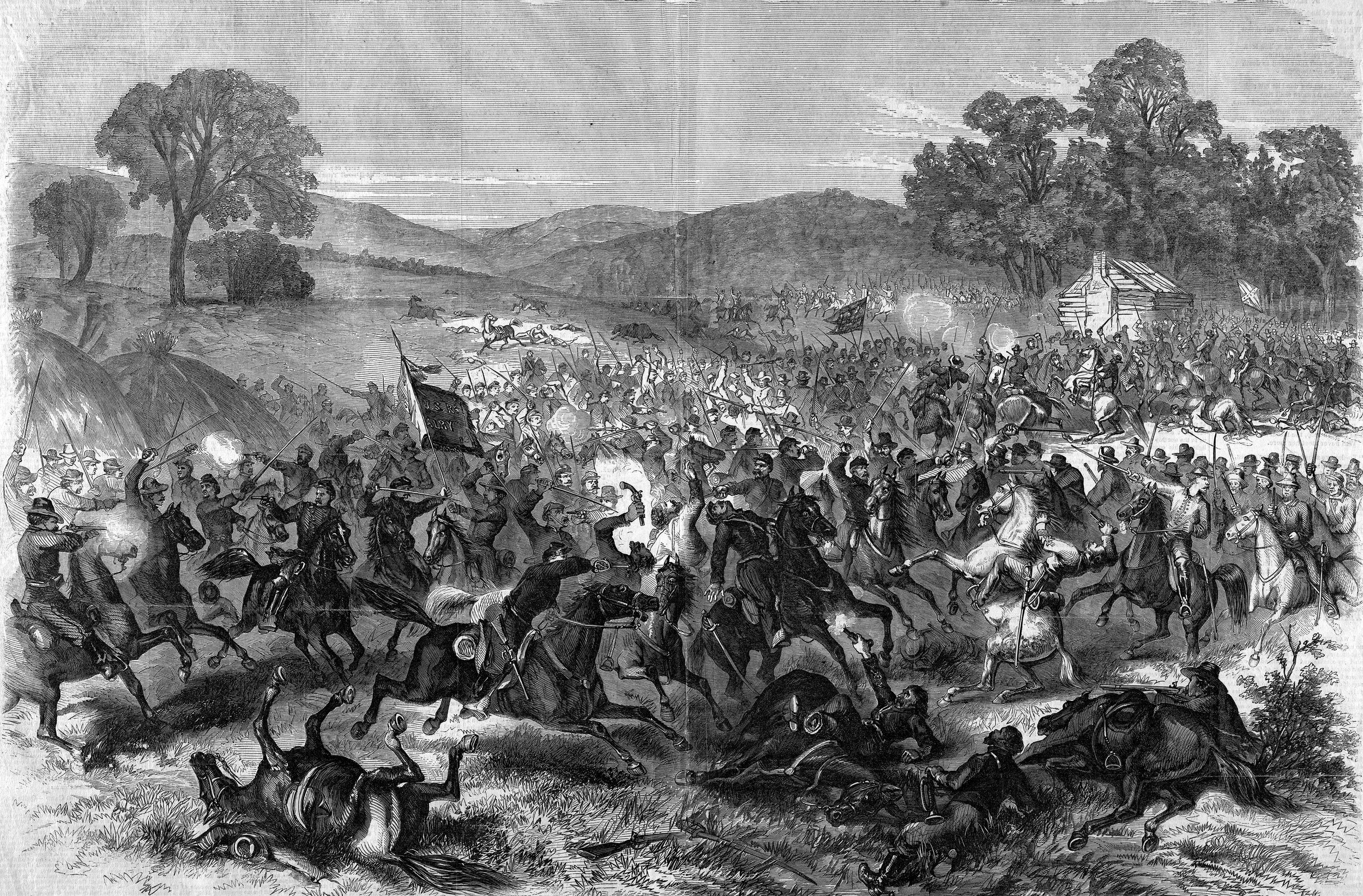

The Federals formed columns and made for the Confederate barricade at a trot. As the Federals increased their pace, pickets from the 9th Virginia rushed back for the barricade and unwittingly masked their comrades’ fire. The lead Federals overtook the Virginia pickets, and all arrived at the same instant to crash through the Rebel barrier. Unwilling to retreat, Davis ordered a counter-charge. The Federals shot his horse out from under him, and the 50-year-old West Pointer fell captive as Yankees boiled over the barricade and rushed up the street on the heels of the Rebel survivors.

Giving way before the onslaught, Captain Frank Bond turned his 40 1st Marylanders onto a side street and wheeled his men about by section, quickly reversing the column’s direction. As the Federals swept by, Bond launched his men back onto the street, and drove into Dahlgren’s open flank. Mounted reserves from the 5th North Carolina and 13th Virginia charged the head of the Federals, and the fighting became hand to hand. Bond recalled Sergeant Hammond Dorsey of the 1st Maryland, hewing left and right, cutting down several men. “[T]he last of them was a bugler, by this time in full flight,” and as he leaned over his horse’s neck, the brass bugle shielded him; “repeated blows were necessary” to bring him down.

Dahlgren and the rest of the Federals now fell back through the town square, and Richmond fed in Company D, 18th Pennsylvania. These troopers rushed forward on foot as sharpshooters, their carbines at right shoulder shift and moving at the quickstep. The Confederates charged forward, and the Pennsylvanians opened fire, clearing a rash of saddles and rushing forward as the Rebels withdrew. This halted the Confederate charge, but the buildings in the town fractured the lines of sight—isolating small pockets of combatants from one another—allowing a victory on one block to be overturned by a reverse on the next as Chambliss rallied his men on the high ground at Zion Reformed Church.

Captain Moorman’s Rebel horse battery now arrived at the church. As the gunners went to load, Chambliss placed sharpshooters in the church cemetery, and on either side of the street, where their concentric fire forced the Federal sharpshooters back down the hill. Chambliss pressed after the Federals, and as Dahlgren moved to counter the enemy, he received a bullet through his foot. Rapidly losing blood, Dahlgren retired to the rear, and surgeons later amputated his leg below the knee.

Richmond marshaled another squadron of the 18th Pennsylvania, plus troops from the 1st Vermont, and sent them charging back for Chambliss’s line at the church. Quick in reply, Chambliss ordered a counterattack, and troopers from North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland spurred forward with a yell. Civilian W. W. Jacobs watched the chaos from the rooftop of the Eagle Hotel, where he had a bird’s-eye view of the fighting: “The cutting and slashing was beyond description … the steel blades circling, waving, parrying, thrusting and cutting, some reflecting the bright sunlight, others crimsoned in gore…. The contending forces were so intermingled that sometimes two or more men were cutting at one.”

Captain Charles Snyder struck down three Confederates, then took a gunshot to the abdomen and a cut across his head that dropped him in the street as more Rebels surged into the fight. Three officers from the 18th Pennsylvania soon joined Snyder on the cobblestones of the square—Captain Henry Potter, Lieutenant William Lawes, and Captain Pennypacker all fell or were captured in the desperate fighting. Richmond responded by sending forward more sharpshooters. Horace Ide of the 1st Vermont Cavalry recalled moving up through the Hagerstown streets: “We deployed down the cross streets as skirmishers, hiding behind the houses and firing around corners. I saw a squad of them and resting beside a telegraph pole fired [m]y carbine. I didn’t know as I hit them, but they dodged mightily sudden. At one time we came on quite a lot of them, three to one, and saved ourselves by running back through [a] house.”

Richmond’s two-tiered assaults of mounted charges and dismounted sharpshooters finally swept the square clear of the enemy, and Hagerstown’s civilians also pitched into the fight. A union trooper later recalled “After we passed the square… an old citizen came out of a house with a musket in his hand and fell in with our boys, loading and firing after the rebels. He was shot down before he crossed the second block.” Not all the inhabitants supported the Federal cause, and a woman firing from inside a house shot down and killed Sergeant Joseph Brown of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Despite Rebel forces perched north and east, Richmond’s lone brigade still held the center of town, while Elder’s battery kept the Federal east flank secure and continued trading rounds with Chew’s gunners. A standoff developed in the center of Hagerstown as each side paused to regroup, and Lee’s wagons remained parked above the town with no route open to Williamsport. That changed with the arrival of General Albert Iverson’s North Carolina infantry.

As the wagons of Iverson’s brigade waited above Hagerstown, his men came forward and began deploying as skirmishers. These men suffered massed casualties on the first day at Gettysburg, and the survivors wanted revenge as they pushed forward and began firing from house to house. The buildings and streets were a hindrance to the cavalry, but these same obstacles were welcome havens for the infantry. Firing from stair steps, porches, and around corners, Iverson’s men advanced block by block, alley by alley, and began placing men on rooftops as they went. “We found ourselves being gradually forced back,” recalled a New England trooper.

“When we found the bullets coming down the sidestreets we would fall back another street and so continue.” The Rebel infantry’s rifled muskets were proving too much for the Federal’s breech-loading carbines. “When we got there, the Yankees had possession of the town,” bragged a Tar Heel infantryman, “but we … soon had the town and the Yankees before us running.”

Richmond now ordered a retreat and the Federals pulled back to the edge of town to link with Custer and Kilpatrick. Despite surrendering the town, all was not lost. Kilpatrick and Custer’s Wolverines continued to hold the Williamsport turnpike and Lee’s wagons still sat trapped above Hagerstown. As the battle noise died out in Hagerstown, cannon fire erupted six miles away from Williamsport.

Buford’s brigades had encountered a novel defense built by Brigadier General Daniel Imboden from Stuart’s Cavalry Division on July 6. Composed of cavalry, walking wounded, armed teamsters, and 26 pieces of artillery, Imboden’s ad hoc line before Williamsport bent but never broke under Buford’s repeated attacks. Kilpatrick eventually sent Custer’s brigade to support Buford, but Rebel artillery shattered Custer’s advance. With the Wolverines reeling, and the sun approaching the horizon, Buford had little option but to retire. Custer followed suit and turned off the turnpike for the Downsville Road, ending what became known as the “Wagoner’s Fight.”Colonel Richmond was now standing alone before Stuart’s forces in Hagerstown.

After hours of fighting in the streets, Stuart could finally maneuver on open ground and he pressed out of town, hoping to pin Richmond on the turnpike ahead; a straight, macadamized road bordered with tall stone walls. Pastures rolled on either side of the pike and Stuart placed Chambliss in the lead, with Ferguson following through the fields beside the road. Robertson’s and Jones’ men followed in reserve.

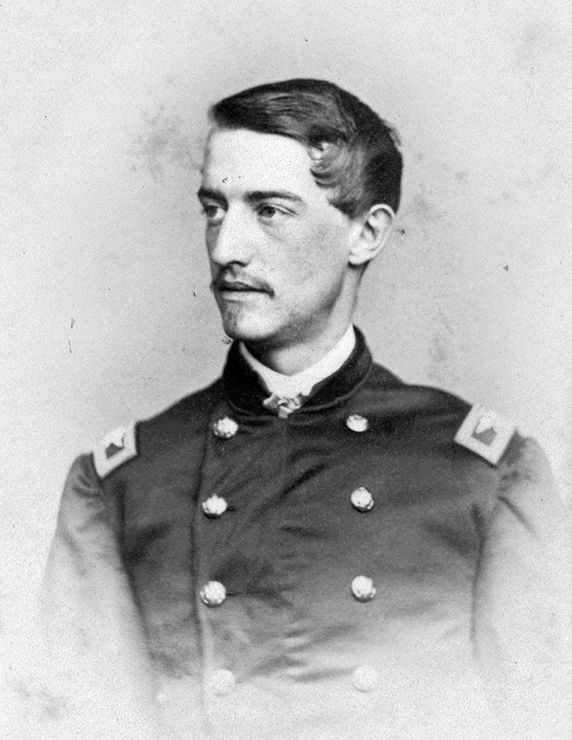

Richmond retired down the pike with the 5th New York and Elder’s battery guarding the rear. Lieutenant Elder had served a prior hitch in the 2nd U.S. Artillery before the war and rose to 1st sergeant by 1858. He reenlisted in 1861, gained a commission, and received notice for gallantry at the Battle of Antietam. With the sun now dropping, Elder halted a two-gun section on a ridge a mile out of town and began lobbing shells at the coming Southerners while Richmond dismounted sharpshooters in support. Charles McVicar, a gunner with Chew’s Rebel horse battery, wrote, “They are holding their position and we have taken a stand in the pike. Our guns recoiling, bury themselves in the mud. Thought we were done for.” McVicar continued, marking the range of the enemy: “Their battery is 400 yards distant. We are under a rapidly advancing line of [enemy] sharpshooters…. We don’t mind shell but these little bees zipping by make us nervous. The cavalry charged and we are firing.”

As Chambliss and his troopers closed, the Federal sharpshooters withdrew, and Elder redeployed at the next ridge down the road, and again opened fire as the 9th Virginia advanced down the pike in a column of fours. The Union gunners loaded canister, and the 9th Virginia split their column down the middle, forming two separate columns of twos, each wide to either side of the stone fences bordering the turnpike, with a gap between the columns. Elder’s guns fired at 20 paces, so close the canister had not spread when the load struck a single trooper square in the chest. “[The] charge of canister, before escaping from the net of wire which enclosed it, struck one of our men…. [He] fell heavily to the ground.” The Confederates sprinted over the remains of their comrade and closed on the enemy guns.

A Federal gunner knocked one of the Virginians from his horse with a rammer, and the rest of the Virginians came under fire from Federal sharpshooters posted behind the fences on either side of the pike. The Rebels swerved at this sudden fire and jumped the stone fence bordering the road in a ragged fashion. Elder’s drivers bolted forward in the confusion, limbered the guns, and made their getaway in a brilliant display of horsemanship.

“We fought over every foot of ground from Hagerstown to Williamsport,” recalled a Union officer. “Every time they charged, they were met with grape and canister.” Richmond also praised his gun teams: “Too much credit cannot be given to Lieutenant Elder…. [T]he men of his battery are also deserving of special mention for their bravery and good conduct under fire.”

Stuart responded with Lieutenant Colonel Vincent Witcher’s 34th Virginia Battalion from Ferguson’s brigade. They dismounted left of the pike and raked the Federals with a deadly fire that cleared a number of Yankee saddles. The rest of Ferguson’s men advanced, mounted as the 34th reloaded, and called for the Federals to surrender. Captain Beauman of the 1st Vermont yelled back, “I don’t see it,” and vaulted his horse over the turnpike’s wall with the remains of his squadron. He rode over a crest of rocky ground cut through with fences and vaulted the partitions as if on a fox hunt and Richmond retired down the pike with Elder’s guns in tow.

Falling back to the next ridge, Richmond switched tactics and ordered two squadrons from the 5th New York to charge forward, screen the retreat, and stall the Confederate pursuit. Colonel James Gordon’s 5th North Carolina saw the Federal attack coming, closed ranks, and spurred ahead. They crashed into the New Yorkers with revolvers blazing and shattered the Federal charge. Captain James Penfield of the 5th New York rode in the front rank. His horse fell dead in the road, and Penfield suffered a hard cut from a saber as the Tar Heels stormed through the Yankee ranks from front to rear. Stuart later wrote Gordon led the charge and exhibited “…individual prowess deserving special commendation.”

Still determined to buy time, Richmond again rallied his dwindling squadrons east of the road in the last light of the day. He placed two of Elder’s guns behind the stone fence bordering the pike, and set a line of sharpshooters across the road. Stuart glassed the imposing new position and called on Jones to send up fresh troops. Col. Lunsford Lomax trotted forward with his 11th Virginia Cavalry, studied the Federal position, and paused. The pair of enemy guns protruded from a tall stone fence that framed a large pasture beside the pike. From there the guns could rake the roadway and support the Federal sharpshooters holding the pike.

Lomax formed his men and had them check the loads on their revolvers; orders circulated for all to hold their fire until they gained the enemy line. Sergeants squared the ranks a final time, and Lomax turned onto the pike in a column of fours, crested the rise, and started the charge with 200 yards to go. Lieutenant John Blue of the 11th Virginia remembered the Federals crouching behind the wall: “Not a man could be seen, not a gun fired, all was silent as the grave. We well knew what this silence meant and what to expect any moment.”

Blue and his troopers rolled on, revolvers pointing skyward, bracing for the storm. “It appeared to me that I was riding on a line with, and looking straight into, the mouth of a twelve-pounder which protruded through the stone fence. It is surprising how rapid thoughts will follow each other when a person expects the next breath he draws may be his last.” At one hundred yards, the guns erupted, and canister sprayed down the pike. Blue’s horse tumbled dead in the road, pinning Blue beneath as his comrades hurtled past.

Rolling on, Lomax’s men sprinted for the sharpshooters barring the pike and fired their revolvers. The Federals broke on contact, and the Rebels swept up a number of prisoners and enemy horses. Elder’s two guns, however, remained behind the stone fence bordering the pike, and their drivers now sprinted forward to pull them out of harm’s way. As Lomax rallied his men, he spotted two squadrons of Union cavalry moving to support the guns in the stone-ringed pasture. The turnpike fence provided excellent cover to the Federals, and the only way through was a gap in the fence along the road. Both parties bolted for the opening, the Virginians determined to take the gap and the guns beyond, and the Federals determined to cover their battery. The two sides met just inside the wall, where “the fight waxed hot and bloody.” Pistols flashed close and sabers thudded home in gritty collisions of men and horses. The Virginians managed to take the field, but the outnumbered Federals again won the time for Elder’s drivers to limber the guns and make their escape.

Lomax’s attack swept up over 100 prisoners, and this proved the last straw for Richmond. “The enemy pressed my command so closely as to throw it into considerable confusion.” Worse still, Richmond now began taking fire from a Confederate horse battery, just arriving from Williamsport on the turnpike. Richmond had done all anyone could expect and more. He turned on the Downsville Road and joined Custer and Kilpatrick in the Federal retreat. “I retired with my command in tolerable order in the direction of Boonsborough.”

Elder’s tireless battery again formed the rear guard, trading fire with Chew’s gunners into the evening, the fuses on the shells tracing bright across the twilight sky. “It is 8 1⁄2 o’clock, they are on the run,” wrote Rebel gunner Charles McVicar. “We have driven them six miles; this has been a very heavy division and certainly a hard fight….”

The Potomac continued to rise, and Lee’s trains still clogged the north bank, but Stuart’s brigades repelled two Federal divisions intent on crippling the Confederate retreat, and Lee’s troops were again moving south. Veterans on both sides knew the contest was far from over; Meade’s army was now marching south, the Confederates remained trapped against the river, and more saddle fights would soon occur above the Potomac.

To read more on the cavalry and the role it played in the Gettysburg campaign, visit the author’s website at horsesensehistory.com or pick up a copy of his latest book: Horse Soldiers at Gettysburg: The Cavalryman’s View of the Civil War’s Pivotal Campaign.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments