By Al Hemingway

Shortly after midnight on the morning of April 12, 1861, four men in a rowboat made their way across the pitch-black harbor at Charleston, South Carolina, toward Fort Sumter, an unfinished and architecturally insignificant masonry fort three miles out from the city where the harbor meets the Atlantic Ocean. For three of the men, it was their second trip of the day to the pentagonal-shaped building defiantly flying the Stars and Stripes above its ramparts.

A Warning to Major Anderson

Although the four men headed toward Sumter were self-professed gentlemen—three from Charleston high society, the fourth an aristocratic Virginian—this was no social call. They were there as emissaries of the newly fledged Confederate States of America, born the previous December inside the Carolina Institute Hall in Charleston, where the Ordinance of Secession had been signed and the Palmetto State had become the first star on the Confederacy’s new national flag.

The men in the rowboat were flying a different flag at the moment, the white flag of truce. But if their visit was intended to be peaceable, their message most definitely was not. James Chesnut, Jr., Stephen D. Lee, Alexander R. Chisolm, and Roger A. Pryor clambered ashore at Fort Sumter that night to tell the base commander, Major Robert Anderson, that he had but one hour to surrender the fort and evacuate himself and his undersized garrison of 82 men—or else.

The Kentucky-born Anderson was in an unenviable and unprecedented situation. No state had ever seceded from the Union before; whether it was even legally possible for one to do so was a constitutional question beyond Anderson’s experience or expertise. He had arrived in Charleston the previous November, not long after the election of Abraham Lincoln as the 16th president of the United States had brought Charlestonians pouring into the streets to celebrate the much-hated Lincoln’s election—not out of joy for the “black Republican’s” victory, but because it seemed beyond doubt to presage the end of the Union.

Fort Sumter’s Shortcomings and Lack of Supply

Fort Sumter itself was designed to house a garrison of about 650 men and 135 cannons that were strategically placed in a three tier-style of arrangement circling the fort. The structure was 170 to 190 feet in length, and was 50 feet in height; its walls were five feet thick. The primary purpose of the installation was to strengthen the defenses along the southern coast of the United States. The construction started in 1827 but was still not finished in December 1860. Even worse, approximately half of the guns had not been delivered because of Buchanan’s downsizing of the military during his time in office.

“Few guns were mounted, and these were chiefly on the lowest tier,” noted Sergeant James Chester of Company E, 1st U.S. Artillery. Chester complained that the openings cut into the walls of Sumter for the guns had not been completed on the second tier, so that only the first and third tiers could be used. Union soldiers worked diligently to build up areas of the bastion that sorely needed it. Some continued to demonstrate a positive attitude, believing that they were a match for their adversaries. Chester, however, was a realist. He understood that the enemy had “unlimited labor and material” and that the occupants of Fort Sumter were handicapped by having access only to materials that had been stockpiled from years past.

Despite the shortcomings, Anderson was ordered “to hold possession of the forts in this harbor, and if attacked you are to defend yourself to the last extremity.” Anderson did what he could. He told yet another South Carolina emissary, Colonel J. Johnston Pettigrew of the state militia, that although his (Anderson’s) sympathies were “entirely with the South,” he was sworn to do his duty as a United States officer and “cannot and will not go back.” He called his men to the parade ground, had the chaplain offer a prayer, and instructed the band to play “Hail Columbia.” The die was cast.

Jefferson Davis: “Reduce the Fort”

On January 11, the State of South Carolina called for the immediate surrender of Fort Sumter. Stalling for time, Anderson responded that he did not possess the authority to hand over the fort to anyone. The following day, South Carolina Governor Francis Pickens dispatched the state’s attorney general, I.W. Hayne, to deliver a message to President Buchanan that read in part, “The demand I have made of Major Anderson, and which I now make of you, is suggested because of my earnest desire to avoid the bloodshed which a persistence in your attempt to retain the possession of that fort will cause; and which will be unavailing to secure you that possession, but induce a calamity most deeply to be deplored.”

The Buchanan administration refused to budge. Pickens dispatched a party, led by the state’s attorney general, Andrew Gordon Magrath, to discuss surrender terms with Anderson. Although they tried to “persuade and alarm him,” their efforts were in vain. Anderson informed them that before he would turn Fort Sumter over to them, he would “fire the magazine and blow fort and garrison into the air.” Lines were hardening into cement on both sides.

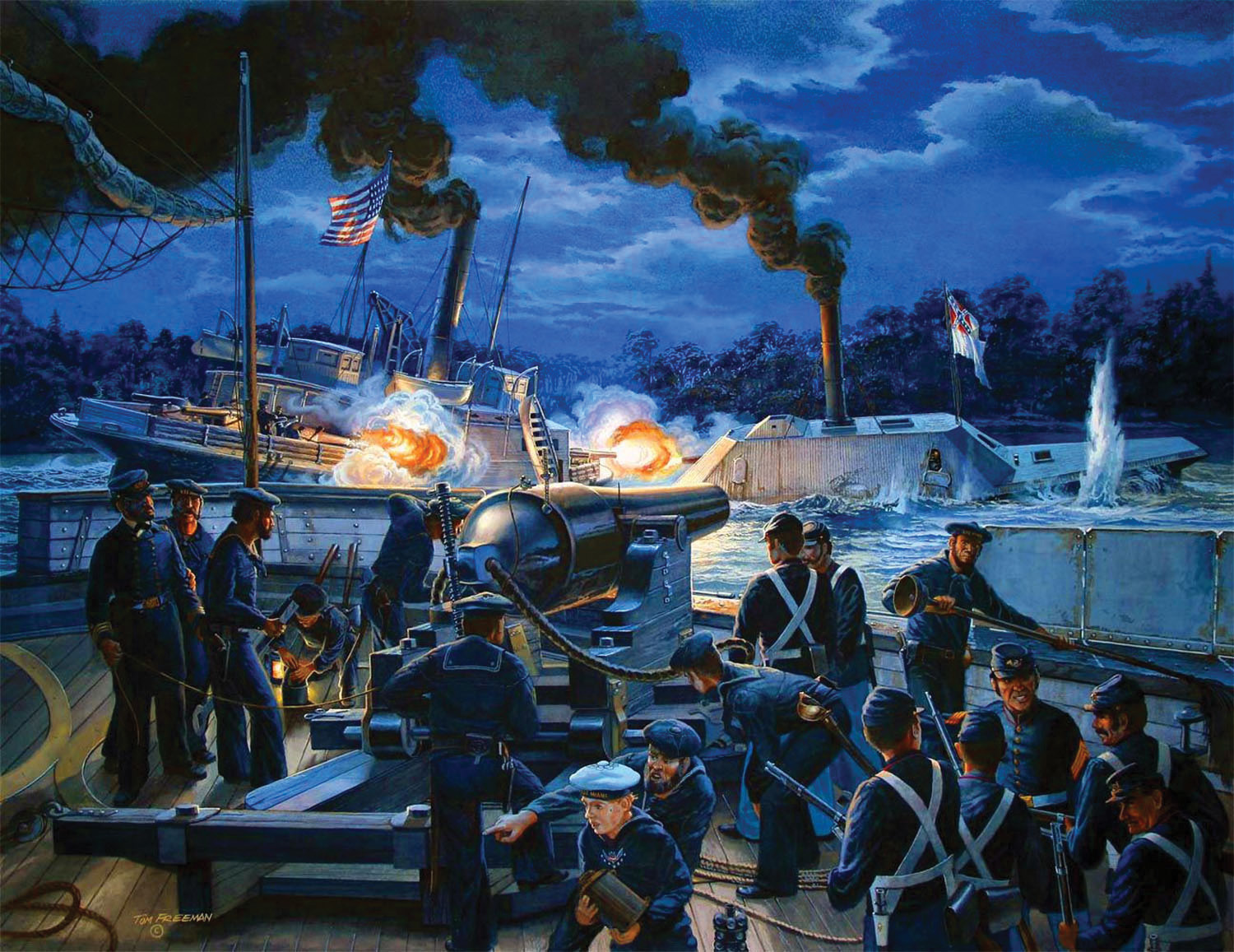

Throughout February, demands for Sumter’s capitulation continued to be sent to Anderson, who promptly denied them. Events continued apace. On February 18, Jefferson Davis resigned his seat in the Senate and was named president of the Confederate States of America. He tried to negotiate with the North by sending a peace commission, but that failed. On March 1, Davis appointed Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard commander of all Confederate troops in the Charleston area.

On March 4, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as president of the United States. In a pointed nod to the people of the South, the president declared, “You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the Government, while I have the most solemn one to ‘preserve, protect,’ and defend’ it.” Lincoln said that violence and bloodshed would not be his policy unless forced on him by the acts of others. On that same day, he received a letter from Anderson saying that he had enough supplies to last approximately four to six weeks. After much haggling with his cabinet, especially from Secretary of State William E. Seward, who had been telling the Confederate delegates that the fort would soon be evacuated, Lincoln decided that he would make another attempt to reinforce Fort Sumter.

Little did Anderson know, but Lincoln’s telegram informing him of a resupply mission had been intercepted by the Confederates. Fearing the additional firepower from the man o’ wars in Charleston harbor, Jefferson Davis told Beauregard to “reduce the fort.” Ironically, Beauregard would order his artillerymen to begin the bombardment on Fort Sumter early the next morning against his former artillery instructor at West Point.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments