By James Bilder

After 36 days of ferocious combat, the island of Iwo Jima was declared “secure” by departing U.S. Marines on March 26, 1945.

In fact, an estimated 3,000 Japanese troops who refused to surrender were holed up in a subterranean network on the island and it would be the job of the U.S. Army’s 147th Infantry Regiment to root them out.

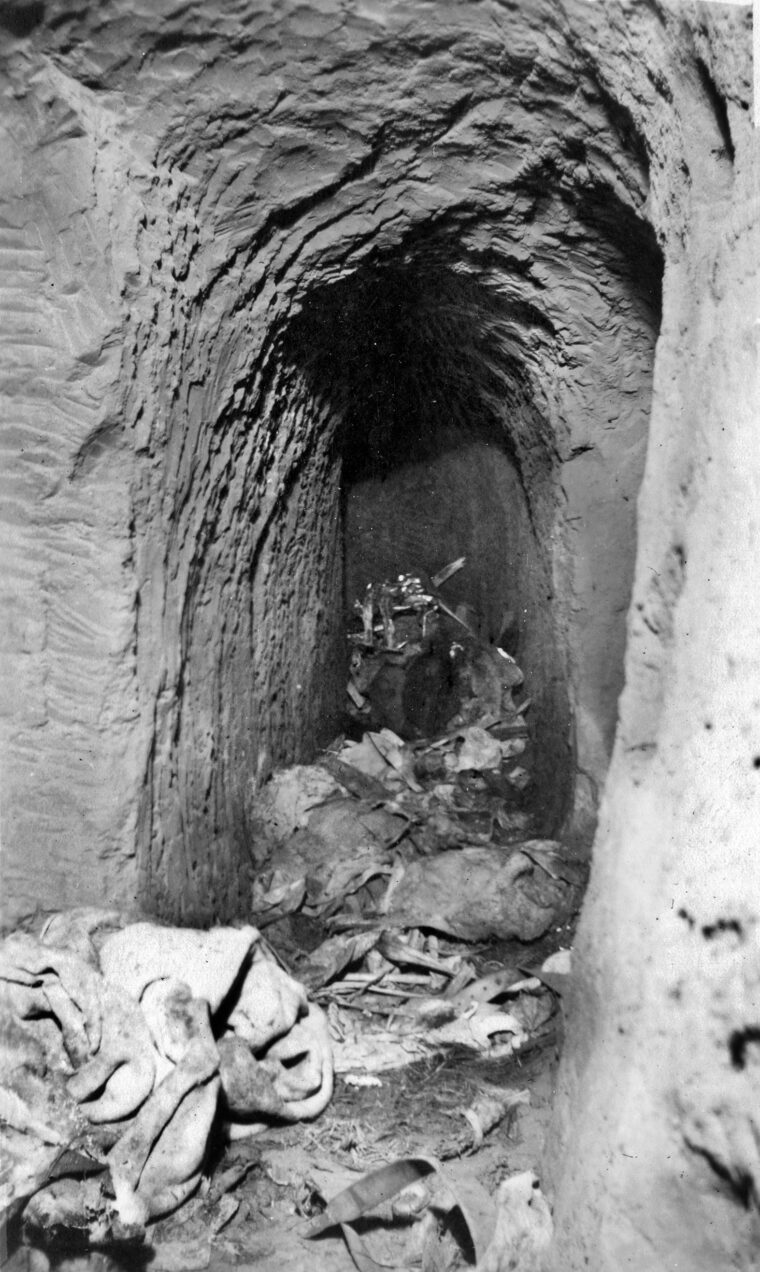

To nearly any follower of U.S. military history the image of an American soldier, flashlight and sidearm in hand, seeking out an enemy deep below the surface of Asian soil conjures the famous “tunnel rats” of the Vietnam War. But more than two decades before Vietnam, there were the “Cave Men” of Iwo Jima, as the 147th Infantry Regiment took to calling themselves. And they would soon find that there was very little about the island that would truly be as it appeared.

Iwo Jima was, and remains, covered in black volcanic sand and considerable mystery. Though one thing that is crystal clear about the island is the incredible performance of the U.S. Marines who fought there—the capture of Iwo Jima was the pinnacle of achievement and produced the iconic image of the Corps with the flag raising on Mount Suribachi. Of the 83 Medals of Honor awarded to U.S. Marines in World War II, 22 of them were for actions on Iwo Jima. The simple mention of “Iwo” deservedly sends an almost electrical sense of pride through the heart of every Leatherneck. Joe Rosenthal’s photo depicting the raising of the large American flag on the summit of Suribachi has become not only the public’s primary symbol for the Marine Corps, but a symbol of the U.S. victory in World War II on both sides of the globe.

Some 6,800 Marines were killed and roughly three times that number wounded on Iwo Jima. The 26,000 casualties make it the only battle during the war in which the Marines suffered more than the Japanese. The proportionate losses of Marines at Iwo are greater than those suffered by the Americans at Normandy on D-Day. Adm. Chester Nimitz, commander of U.S. forces in the Central Pacific, said that at Iwo Jima, “Uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

Truer words have rarely been spoken, but few realize that some U.S. Army infantrymen were among the Americans who served on Iwo Jima and that Nimitz’s words apply to their battle performance as well. In order to learn a greater comprehensive history of the battle for Iwo Jima and the Army regiment that fought there, one has to look not only back but below, well below, the surface that covers and conceals that historic island. Japanese Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi, commanding the defenders of Iwo Jima, had his men dig a vast series of catacombs and tunnels that ran underneath both the north and south sides of the island. The labyrinth contained over 1,500 rooms and provided seemingly endless spaces for diehard Japanese soldiers to hide.

It was estimated by General Harry Schmidt, commander of Marines’ V Amphibious Corps, that there were probably some 100 to 300 surviving Japanese soldiers underground ready to continue to resist in the spring of 1945. In reality, it was closer to 10 times that estimate. However, the Americans believed that a single Army regiment could easily garrison Iwo Jima and eliminate a few hundred beaten and half-dead enemy troops who had scurried underground to lick what could only be regarded as fatal wounds.

Yes, this would only be a “mop up” of what little the Marines had left behind as they were withdrawn from Iwo to recuperate and prepare for their next hellish invasion on the way to Japan. Who better to clean up after the Marines than the Army’s 147th Regiment? Contrary to popular thought, American soldiers of the Marines and Army fought together in many Pacific battles, frequently as a composite unit. The use of what was referred to during the war as a “CAM” (Composite Army-Marine) unit was not a concept new to the Pacific theater or even to World War II. Army and Marine infantry had first fought alongside each other during the American Revolution at the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777. They would fight side by side on many occasions during the Pacific War.

Iwo Jima became a CAM operation even if few historians know or care enough to note it. The soldiers of the Army’s 147th Regiment have been dubbed “The Gypsies of the Pacific” by Tom McLeod, who authored the regiment’s unofficial history Always Ready—The Story of the United States 147th Infantry Regiment and is the curator of the Museum of the Pacific in Texas. McLeod’s father was Capt. Prentiss R. McLeod, who served in the 147th’s ranks during the war. Originally attached to the Army’s 37th Infantry “Buckeye” Division of the Ohio National Guard, most of its men were from Cincinnati and southwest Ohio. The 37th Division arrived in Fiji in April 1942 to garrison and defend the surrounding islands. In early 1942, the Army wanted to “triangularize” its infantry divisions, cutting them down from the four-regiment composition of World War I to three regiments each for the new conflict. As a result, the 129th, 145th, and 148th Infantry Regiments were to remain together as the newly reorganized 37th Infantry Division.

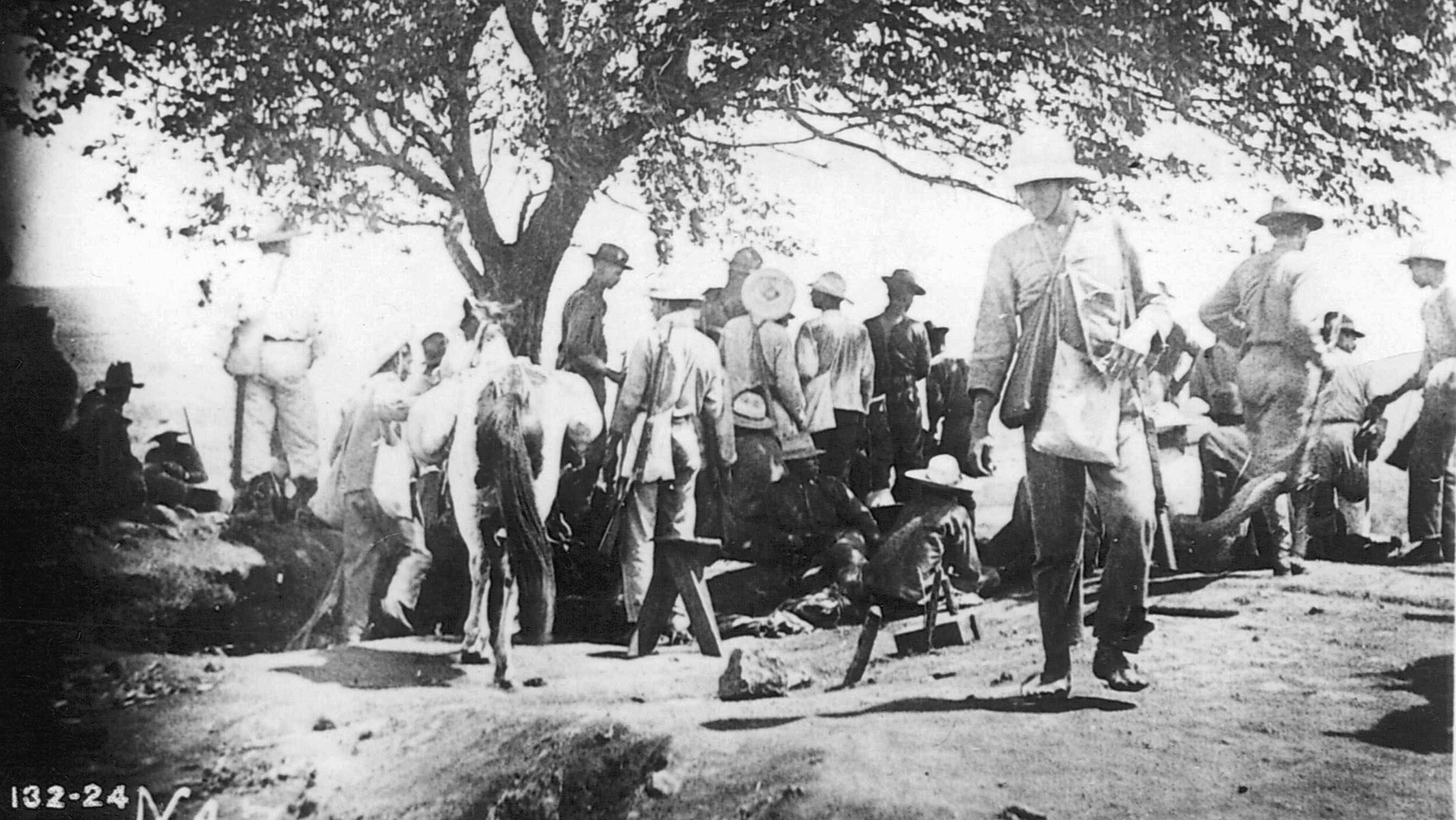

The reorganization left the 147th Regiment officially “orphaned.” But the Army quickly rectified this by sending the unit to Guadalcanal, where infantry was desperately needed. The Marines had first landed on Guadalcanal on August 7, 1942. Adm. William F. “Bull” Halsey, commanding U.S. forces in the Guadalcanal offensive, ordered the 147th Regiment to the island on October 20, 1942. When the Japanese finally evacuated the island in February 1943, the unit stayed to mop up straggling enemy soldiers.

It was first on “secured” Guadalcanal where infantrymen, specifically Army soldiers, received a baptism by fire in the fine art of extracting diehard Japanese defenders from caves and tunnels without getting themselves killed in the process. It was soldiers of the 147th Regiment who were among the first to employ the tactics of “blowtorch” and “corkscrew” to kill the enemy troops underground.

Orders came down on July 31, 1943, permanently detaching the 147th Regiment from the 37th Division. Between May 1943 and March 1945, the 147th garrisoned various islands including Samoa, New Caledonia, Emirau, and then back to New Caledonia again. While garrisoning Emirau, the 147th Regiment’s commander, Col. William B. Tuttle, Jr., insisted on a daily training regimen that sharpened skills on two-man flamethrower (“blowtorch”) teams as well as three-man BAR/satchel charge teams (“Corkscrew”) to perfect tactics in neutralizing enemy strongpoints and hiding places. Tuttle’s troops, even cooks and clerks, were required to become proficient in various Japanese weapons as well.

As December 1944 approached, the unit’s new commander, Colonel Robert F Johnson, informed his regiment, “We’re going right up into Tojo’s front yard.” The location was still classified, but when Johnson added to his remarks, “every man must know this and every man must be prepared,” there could be no doubt that this would be another Pacific perdition.

Mandated troop rotations in the Pacific theater had reduced the number of highly trained and combat experienced troops in the 147th by about 50 percent. Johnson had to essentially start from scratch as he ordered crash courses in such things as amphibious landings, jungle warfare, and marksmanship. The 147th began to load transports on February 24, 1945, and sailed eight days later for Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Eniwetok had been taken a year earlier by the Marines and was now the staging area for the Iwo Jima invasion forces. The 147th had been given the code name of Task Unit 11.1.2. It consisted of three battalions of infantry (approximately 3,000 men), an anti-tank company, a cannon company, and headquarters troops. The 147th arrived at Eniwetok on March 14 and was told that the regiment would remain there until month’s end when it would begin its garrison duties on Iwo.

The reprieve was extremely short lived as that same day Colonel Johnson received orders which read, “Request Task Unit 11.1.2 carrying 147th Inf. be directed proceed to Iwo Jima earliest practicable date.” The men of the 147th were leaving their staging area mere hours after their arrival. They were to be attached to the 3rd Marine Division. By this time, every man knew where they were going, what was happening there, and just how dangerous and desperate the situation must be. The regiment arrived off the coast of Iwo Jima on March 20 at around 1:30 in the afternoon. The soldiers could see as well as smell the smoldering and battered island.

Two years earlier at Guadalcanal, the 147th had fought alongside Marines and the regiment had later garrisoned with them on Emirau. It was thought that few organizations could be as well suited as the 147th Regiment to follow the Marines in at Iwo Jima. The regiment disembarked at “Purple Beach” at dawn on March 21, 1945. The sounds of battle were still very much in the air as the north end of the island had not yet been fully secured. The men were assembled near Airfield No. 2.

Initially, the 147th was to watch the coastline and then assume garrison duties on Iwo eliminating any pockets of resistance and nabbing any enemy stragglers. Those orders were changed after they arrived off the island’s coast. Their new mission would be to effectively join the battle by performing “a relief in place” of elements of the 3rd Marines.

On March 30th, a patrol from the 1st Battalion killed two Japanese sentries at a cave entrance. When the Americans cautiously entered the cave, they discovered a vegetable garden, chickens, a couple of cows, American medical supplies, weapons, and ammunition. The enemy could steal just as effectively as they could fight.

In order to truly “secure” Iwo, Colonel Johnson decided on the tactical use of combat patrols to engage the enemy, carefully planned ambushes which consisted of skillfully pre-sighted kill zones, and “cave cleanings” conducted by men who would later dub themselves “cave men” consisting of soldiers who would go into the enemy’s caves and tunnels and fight it out with them.

James McGuire of Bravo Company remembered that the cave clearing teams “were equipped with guts, flashlights, and pistols.” James Ahern, a platoon leader in Fox Company, described how courageous and clever the Japanese were in defending their underground system. Openings were often defended by marksmen who could pick off soldiers and Marines at a distance. If someone got close enough to throw a grenade, the enemy often had another man “playing outfield” who was prepared to catch the grenade and throw it back. McGuire was twice wounded on the same occasion by this tactic when attacking a cave. He first threw in a phosphorous grenade only to have it fly back at him. He followed up with a fragmentation grenade only to have the same thing occur. He then called up a flamethrower and finally neutralized the cave.

American soldiers equipped with flame-throwers sometimes caused the Japanese to shelter in place in a tunnel or cave, requiring another team to advance on the enemy positions and drop hand grenades or satchel charges into the openings to kill outright, or entomb (corkscrew) the enemy inside. These brutal tactics were often a last resort.

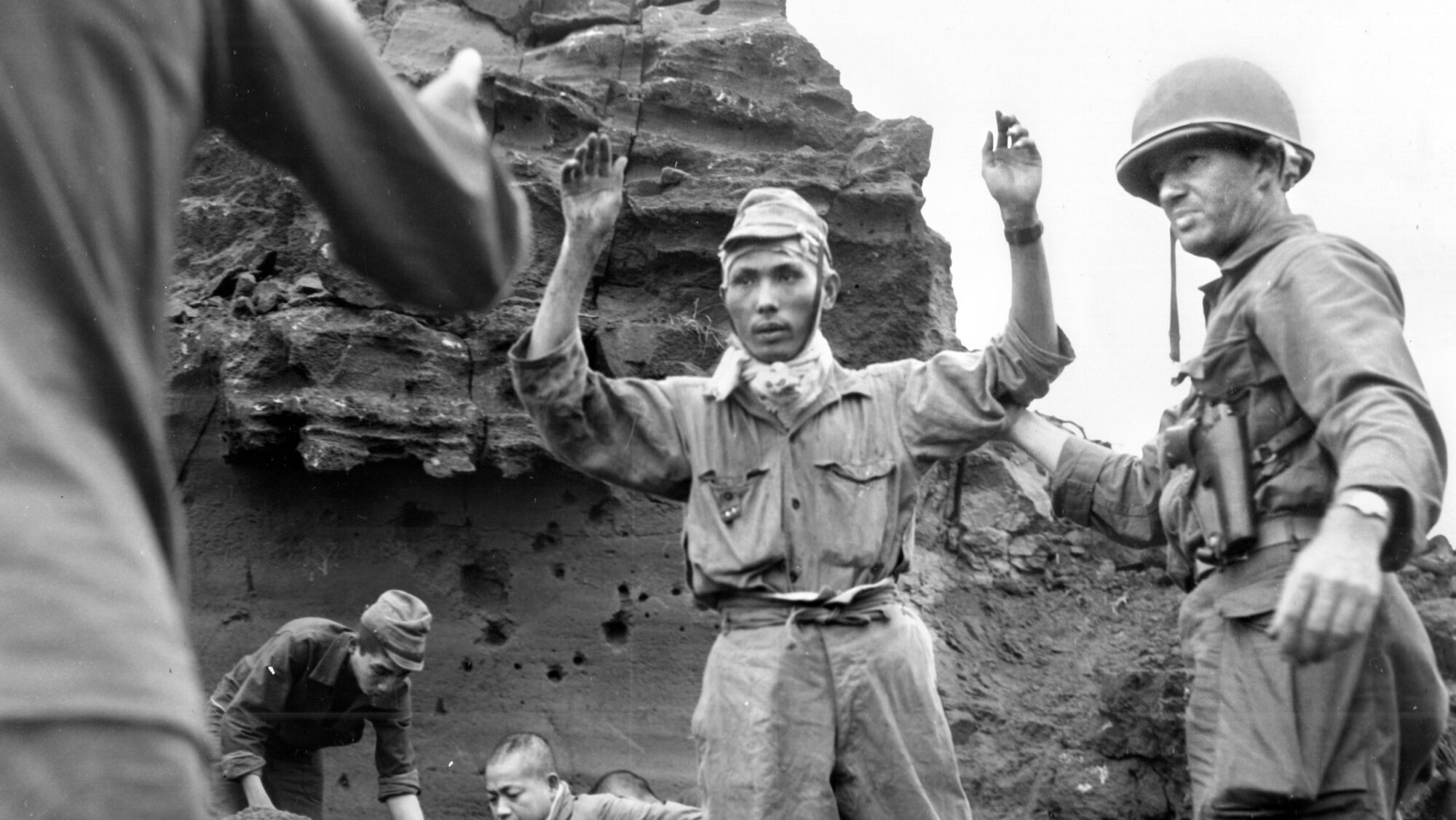

Corporal Edward Mervich of the 147th Regiment wrote, “Our superiors told us that the enemy was more valuable alive because they could write letters home to their families and tell them how good we were treating them. The plan was to convince the Japanese not to resist the invasion of their homeland.”

Technical Sergeant Terry Takeshi Doi, a Nisei (Japanese-American) soldier who was often assisted by Japanese POWs in his work, coaxed many Japanese holdouts into surrendering. Sergeant Doi regularly entered caves and once even approached a pillbox with his shirt removed to show that he was unarmed in an effort to talk to Japanese troops in their native tongue and urge them to follow him to safety. His cumulative efforts convinced many enemy troops to surrender, and he was later awarded the Silver Star for valor.

Food and water, or at least items made to look like supplies, were often used to bait traps for the nocturnal foraging parties consisting of four or five Japanese soldiers. The items were sometimes booby trapped or surrounded by trip wires. Once the waiting Americans were alerted to the presence of enemy troops, a ring of deadly fire would zero in on the pre-sighted area, and any Japanese soldiers caught inside were quickly cut to pieces. Japanese radioman Tsuruji Akikusa (from a naval air group) was once a part of such a foraging party when he became separated from his comrades. He stumbled onto a cache of American weapons and ammunition but was more interested in finding food and water. When he opened a case of Coca-Cola (something he had never encountered before), he nearly drank himself sick, commenting, “The sweet, carbonated beverage was the most delicious thing I have ever tasted in my life.”

Isolated pockets of Japanese soldiers began to compete amongst themselves for foraged supplies and even resorted to killing each other for food and water. Japanese Ensign Satoru Omagari witnessed many such acts and said later, “My experiences changed me fundamentally. I lost faith in humanity…I encountered no glory on Iwo Jima.”

On April 4, 1945, the 9th Marines left Iwo Jima and responsibility for the entire island fell to the 147th. The official figures as of March 31 reported that the 147th had killed 387 Japanese and captured 17. Their own losses were eight dead and 53 wounded.

In early April, the Japanese mustered a task force of approximately 200 men who came from underground near an area called East Boat Basin about halfway up the southeast coast of the island. They attacked a command post there, and the ensuing firefight lasted all night. The attack resulted in an explosion of 6,000 cases of dynamite, causing a blast that literally rocked the entire island. There were no Japanese attackers alive by morning. On April 11, Capt. James Kolb of Able Company was leading a squad-sized patrol on the east side of Iwo Jima to set up an ambush when they spotted two Japanese soldiers coming up from a hole near the area where Kolb had planned his ambush site. Kolb’s men opened fire and killed one of the enemy while wounding the other. The wounded Japanese soldier made it back into the hole and returned to his comrades. He was one of 72 men of the 2nd Mixed Brigade, which had a hospital 100 feet below ground.

Kolb summoned his Nisei interpreter, Sergeant Ritsuevo Tanaka, who spoke to the Japanese commander, Maj. Masaru Inoaka, a senior medical officer, and informed him that their only alternatives were surrender or a gruesome death that combined fire with being buried alive. In a move highly unusual for Japanese soldiers during World War II, Inoaka put the matter to his men for a vote. The vote was 69 to 3 in favor of surrender. Corporal Kyutaro Kojima, one of the three “nay” votes, immediately killed himself while the others were helped to the surface and into American captivity. Kolb had just bagged the largest number of enemy POWs taken at any time during the battle for Iwo Jima. The 147th’s figures for April alone showed 963 Japanese killed and 664 captured. The patrols, ambushes, and cave cleanings were taking their toll. During the days that followed, the Japanese became more willing to surrender. By the end of May 1945, the official month’s count for the 147th Regiment was 252 enemy killed and 186 captured.

Lieutenant James Ahern of Fox Company was leading a patrol on June 4 in the northeast quadrant of Iwo Jima when he and his men discovered what appeared to be General Kuribayashi’s underground headquarters. There were still Japanese troops inside who refused calls to surrender, so Lt. Joseph “Pappy” Lenoir of the Ammunition and Pioneer Platoon was called forward. Lenoir literally had hundreds of gallons of gasoline pumped into the cave and then ordered it ignited. The resulting blast was enhanced by whatever ammunition the Japanese had inside the cave. There were 54 enemy troops who somehow amazingly managed to survive and promptly surrendered. The cave was thoroughly searched, but Kuribayashi’s remains were not found there. Again, Americans found the tunnels exceedingly well equipped with military supplies of all kinds. Even so, things were winding down by the end of June. The figures for that month were 17 Japanese killed and 6 captured.

There is no way of knowing how many Japanese were sealed, atomized, or burned to death inside the caves and tunnels of Iwo Jima, but the total figures for enemy casualties inflicted by the 147th Regiment from March 21 to June 30 include 1,602 killed and 867 captured. In contrast, the 147th had lost15 dead and 144 wounded.

Most of the Japanese captured by the 147th Regiment on Iwo Jima ended up at the POW Camp at Fort Eustis, Virginia, before being repatriated to Japan at the end of the war.

The last Japanese holdouts on Iwo Jima turned out to be machine gunners Matsudo Linsoki and Yamakage Kufuku, who surrendered on January 6, 1949, to U.S. Air Force personnel of the 6000th Support Wing stationed on Iwo Jima (a satellite of Tachikawa Air Base, Japan).

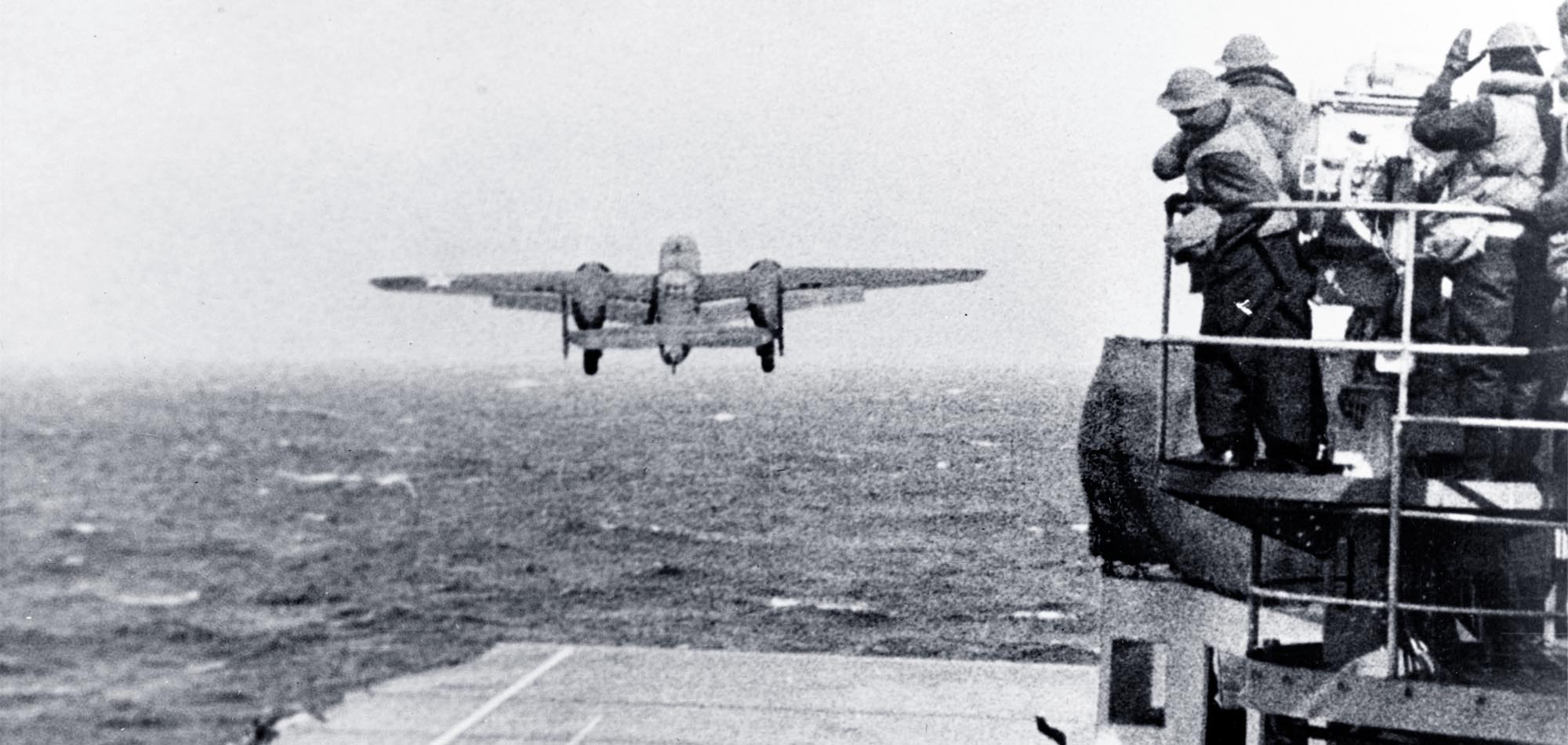

The 1st Battalion of the 147th Regiment was withdrawn from Iwo Jima at the end of June, 1945, and sent to the island of Tinian in the Marianas to help provide security for the Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers that were soon to drop the atomic bombs on Japan. The personnel of the 147th’s cannon and anti-tank companies were converted into infantry to help with the final mopping up on Iwo Jima.

On May 5, a force of 111 men from Charlie Company and 39 from Bravo Company left Iwo Jima to scout the island of Minami some 35 miles to the southeast. It was a volcanic rock of just one and one-half square miles that had nothing on it but a wrecked Japanese plane and a single Korean laborer who was immediately taken prisoner. That day, on the southeast end of Minami, the Army had a flag raising of its own.

Six days after the formal Japanese surrender that ended World War II, the 147th Regiment was sent to Okinawa, performing occupation duty there until December 8, 1945, when it was sent back to the States. The regiment was deactivated on Christmas Day.

In a commendation letter, Lieutenant General Robert C. Richardson, commander of U.S. Army Forces, Pacific Ocean Area, wrote, “(The) members of the 147th Infantry Regiment, whose mission was the destruction of the Japanese forces remaining on Iwo Jima after organized resistance had ended, displayed consistent courage and combat ingenuity in dealing with an enemy determined upon a course of fanatical resistance. Despite conditions of terrain and placement favorable to the Japanese, morale remained at a high level and few casualties were sustained. The military proficiency and devotion to duty constantly managed by the regiment were in great measure responsible for the final security of a vital advance base.”

Author James Bilder resides in Illinois and has written numerous books and articles on World War II historical topics.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments