By Eric Niderost

On February 28, 1942, Governor Ralph Lawrence Carr of Colorado received a telegram from the White House. At that moment he was in his office, surrounded by staff, but routine business had to be put on hold while Carr quickly scanned the missive that came directly from the president of the United States, Franklin Roosevelt. The United States was at war, and no message coming from the nation’s chief executive could be taken lightly.

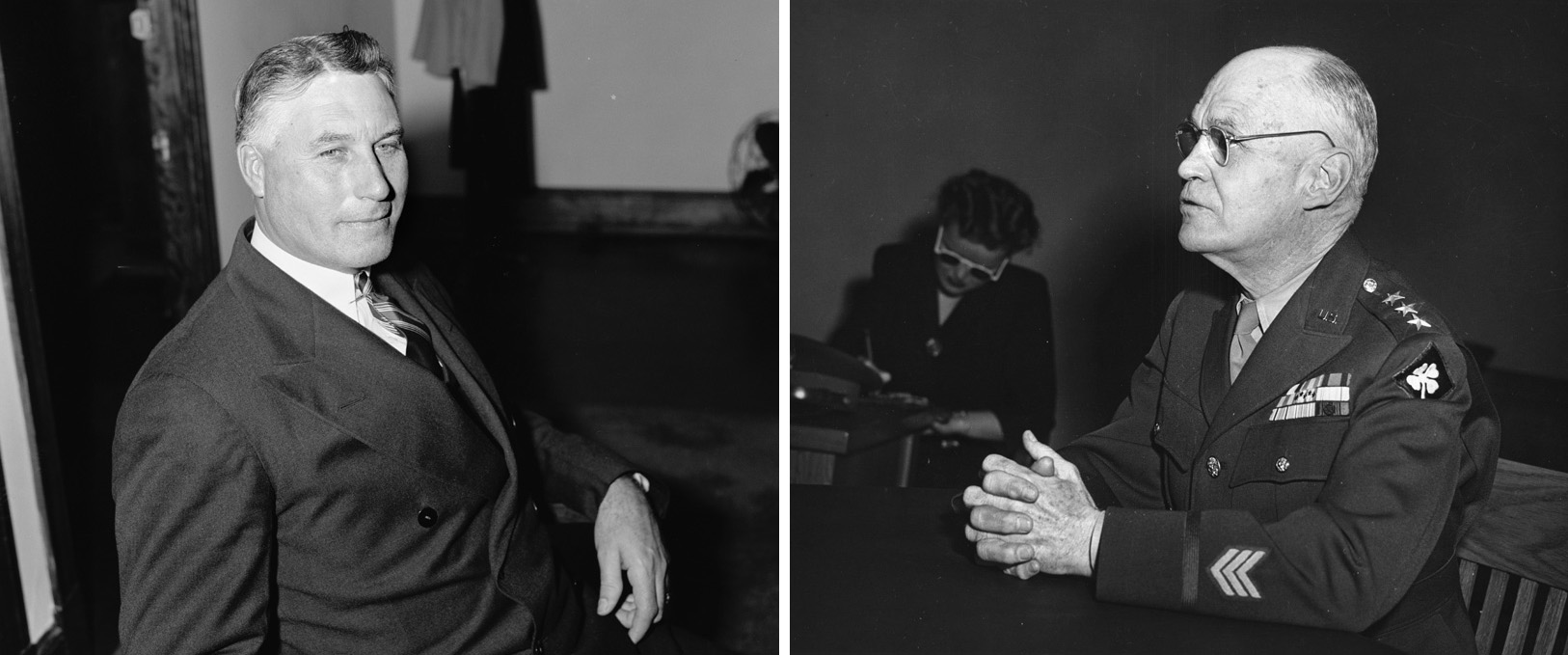

Carr was five feet, eight inches tall but seemed even shorter because of his chubby jowls and protruding belly. The governor was demanding but fair, and his seriousness was leavened by a hearty sense of humor. Governor Carr idolized Abraham Lincoln, who had allowed the public to come and see him personally on a regular basis. The Colorado governor did the same, only modernized the concept: his home phone number was listed in the Denver telephone book. Predictably, his phone rang incessantly day and night.

The governor read the telegram, and his staff nervously noted the warning signs of a major tantrum about to erupt. His face started to turn pink, then red, telltale indications of a mounting fury. The telegram informed Carr that the president had just signed Executive Order 9066, which gave the military a free hand in authorizing security zones along the West Coast. Once these zones were established, the military could bar anyone from entering them—and also, more ominously, eject anyone living there without bothering about due process of law.

The wording of the document was vague and spoke of security threats in an almost generic fashion. But Carr was not fooled—nor was anyone else living in the western half of the country. The main targets of the act were the Japanese Americans, some 120,000 of them, who mainly lived in California, Oregon, and Washington. The governor was incredulous.

“Now, that’s wrong!”Carr shouted loudly, though the outburst was more to himself than to the surrounding staff. His anger was like a force of nature, a hurricane of words that could not be stopped, only endured until it was spent. “They’re American citizens!” he seethed. “Why would a man want to put that kind of order out? Why would a man want to put those people in jail?”

Carr was a Republican and Roosevelt was a Democrat, but Carr’s outburst had little to do with partisan politics. To him the Constitution was the cornerstone of American democracy, a document that gave all citizens rights. If you were a law-abiding American citizen, you could not be denied these rights. Race or ethnicity was of little account in these matters. Carr’s principled stand was going to set him apart from most other politicians of the period.

Estimates vary, but there were between 112,000 and 120,000 Japanese Americans residing in the continental United States. About two-thirds were Nisei, the second generation in America and, since they were born here, full-fledged citizens of this country. The first generation Issei were prohibited from becoming naturalized citizens due to racist laws that were on the books in the first half of the 20th century.

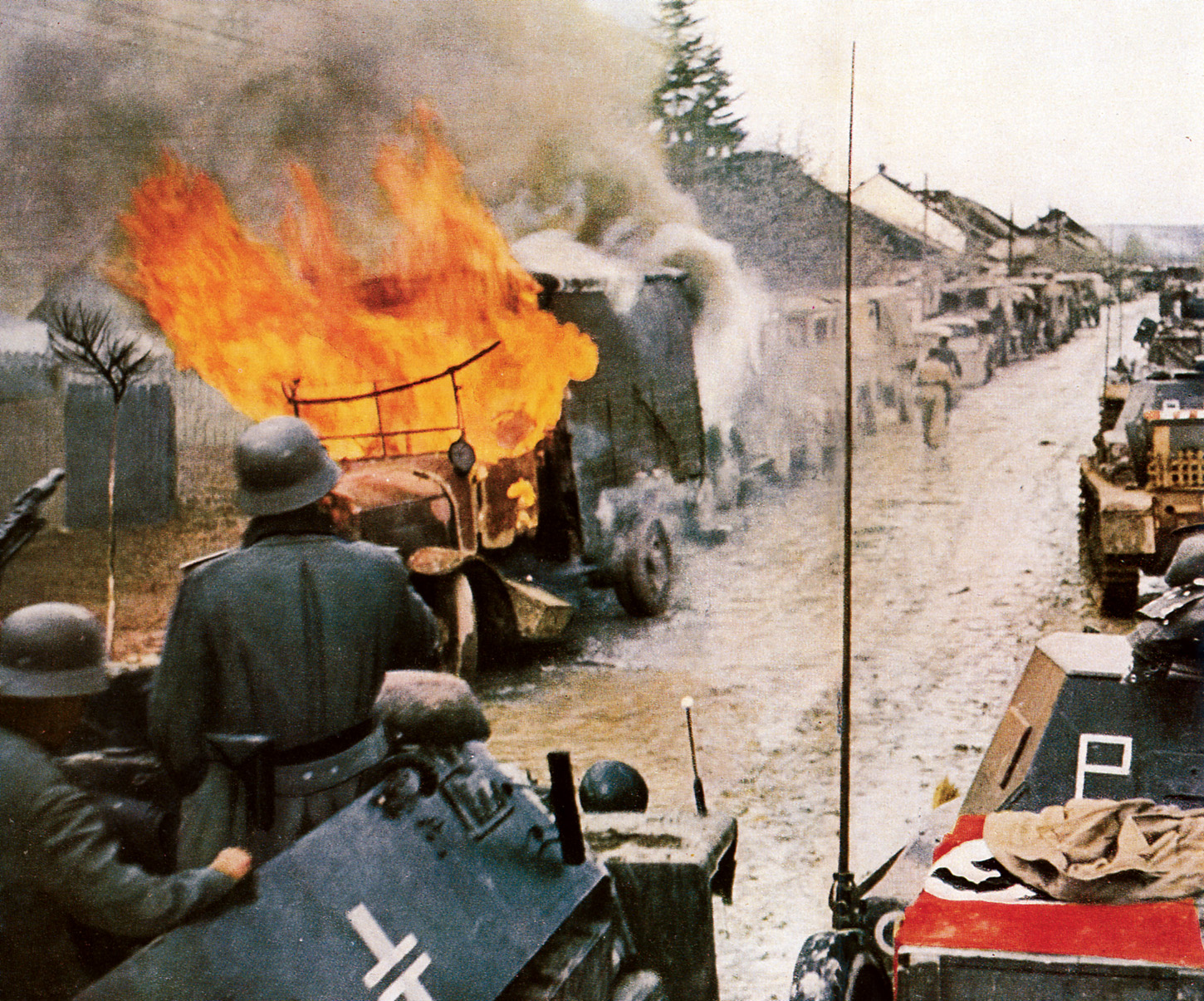

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor unleashed a virulent wave of racism and hysteria throughout the country. Partly because of its geographic position on the Pacific Rim, partly because of its resident Japanese American population, the West Coast, particularly California, was more outspokenly anti-Japanese than most. The seeds of racism, buried in western soil for decades, spouted and grew strong when watered by hysteria and a growing paranoia.

Even the slightest incident was treated like it was the beginning of the apocalypse. On February 23, 1942, for example, the Japanese submarine I-17 surfaced about 1,000 yards from the California coast under the cover of darkness. Commander Kizo Nishino ordered the firing of armor-piercing shells at the Bankline Oil Company refinery at Ellwood, a small community about 12 miles north of Santa Barbara. Damage was minimal, but the attack stoked fears of invasion.

Such fears were augmented by concerns over “fifth columnists,” a then-current term that meant saboteurs and spies. We might call them “terrorists” today. Walter Lippmann, a prominent national newspaper columnist, stoked the flames of paranoia with an article he wrote in the Washington Post titled “The Fifth Column on the Coast.” Lippmann pulled no punches; he advocated the removal of all Japanese Americans from the West Coast. “The Pacific coast,” he declared, “is in imminent danger of being attacked from within and without.”

The invasion fears worked in tandem with racial prejudice of the most overt kind. Agricultural interests like the Grower-Shipper Vegetable Association made no bones about it. “We’ve been charged,” they wrote in an article, “with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons. We might as well be honest. We do. It’s a question of whether the white man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown man.”

Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, head of Fourth Army and the Western Defense Command, quickly got into the act. “The Japanese race,” he stated unequivocally, “is an enemy race, and while many second and third generation Japanese born in the United States [are] possessed of American citizenship, and become ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted….” Then, with the “logic” worthy of an Einstein, DeWitt finished by saying, “The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication such action will be taken [in the future].”

Ralph Carr was one of the few people in the country who dared to raise a voice in defense of the Japanese Americans. A few days after Pearl Harbor the governor made a statewide radio speech that pleaded for toleration and reminded his listeners, “Let us remember that America is the great melting pot of the modern civilized world. From every nation of the globe people have come to the United States who sought to live here under our plan of government.”

Defense of the persecuted and powerless came naturally to Ralph Carr. A native Coloradan, he was born in the town of Rosita in 1887, son of a Scots-Irish pioneer miner. He later said that living in mining camps gave him compassion for the underprivileged. Carr was a newspaperman in his early career and later became a lawyer. He spoke fluent Spanish—self-taught—and often represented Hispanic people from the San Luis Valley. He grew familiar with Japanese Americans in La Jara as well.

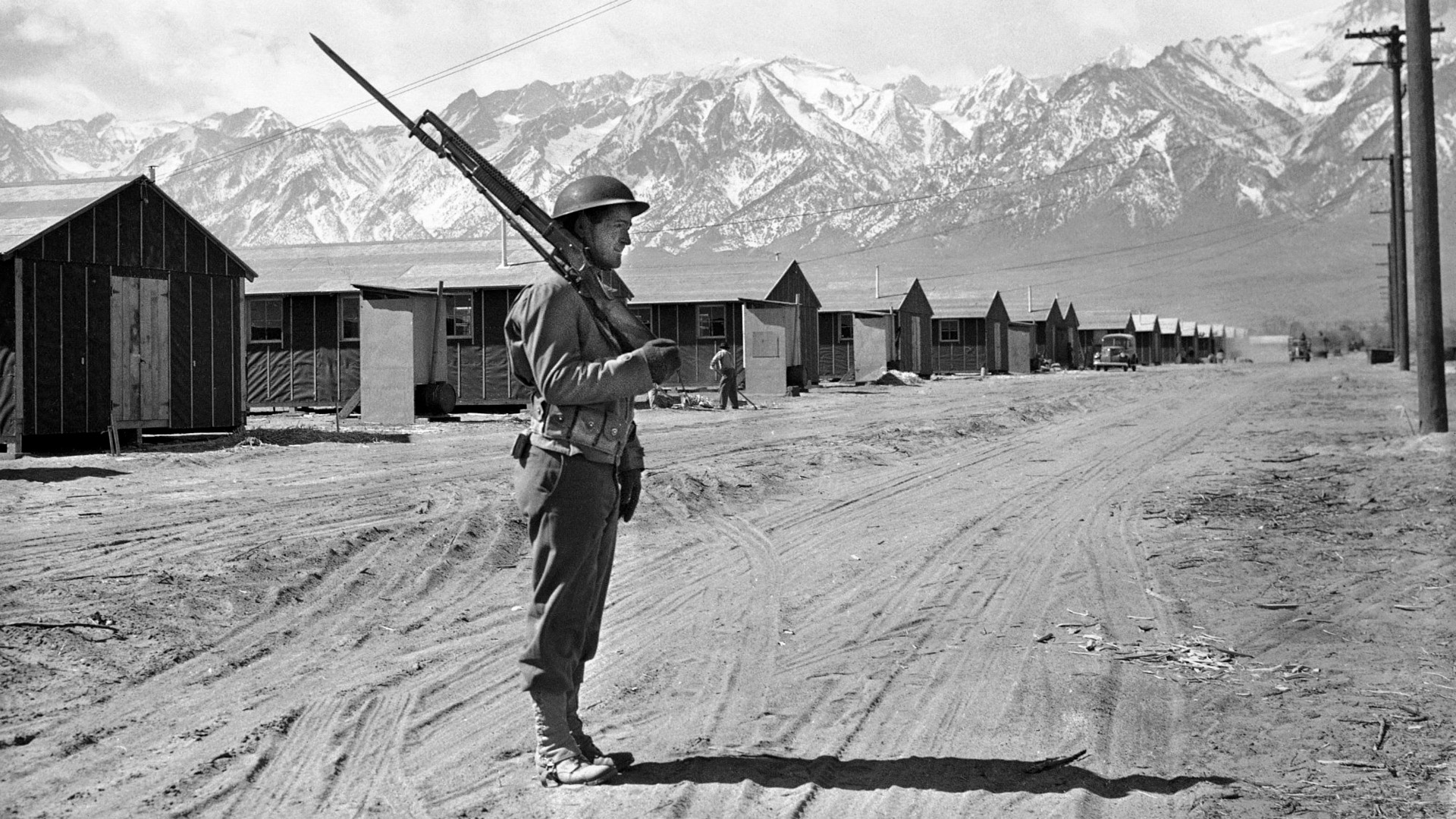

After weeks of growing tensions, President Roosevelt issued his Executive Order 9066, which in essence gave the military powers to remove people from designated zones. Armed with this presidential carte blanche, General DeWitt created Military Areas No. 1 and No. 2 just 10 days after 9066 was issued. Military Area 1 included the western halves of Washington, Oregon, and California and the southern half of Arizona. Military Zone 2 encompassed the remainder of those states.

From February 19 to March 27, the Japanese Americans were given an opportunity to leave voluntarily from the newly created exclusion zones. DeWitt and others in authority hoped most would take the hint, pull up stakes, and leave. It would, among other things, save the government the transportation costs of expelling them. Of course, this was no vacation trip, no temporary absence. Japanese Americans would have to sell homes and other property they might possess. Relatively few, just under 5,000, left during the “voluntary” period.

Those who did leave often found new homes, but others were far less lucky. Clarence Iwao Nishizu, his young brother John, and his friend Jack Tsuhara jumped into their Chevrolet and drove nonstop from Southern California to Littleton, Colorado, in search of work and a sanctuary to ride out the political storm. They hoped to get a job at a seed company but were quickly rejected. They then drove south to the San Luis Valley, and La Jara, Costilla County, where they sought help from a Japanese American farmer. Fearful of his own status among his white neighbors, the farmer refused to employ them.

They tried New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona, but the story was the same. No matter where they went, they found indifference, rejection, or outright hostility. Frustrated, they ended their four-state odyssey by returning to their original home in Orange County. Yet many others found a home in Colorado. Tillie Honda, a nurse from California, took a position at Denver’s Seventh Day Adventist Hospital, a job arranged by a white doctor she knew. She suffered no racism and spent the rest of her life in the mountainous state.

Though a small minority, the Japanese had a long history in Colorado. There were a handful of Japanese there as early as the 1880s, but most were relative transients. After 1900, Colorado’s resident population of Japanese Americans grew modestly. Most were common laborers, railroad workers, miners, rural farmworkers, and factory employees. They suffered racial discrimination at times. There was always white paranoia over the perceived “Yellow Peril,” but on the whole they did well. The 1940 census listed 2,734 Japanese Americans as permanent residents. Most were farmers.

In all about 2,000 Japanese Americans, people like Tillie Honda, found new lives in Colorado during the “voluntary” removal period that finally ended on March 27, 1942. But the pressure on Governor Carr to bar them from entering the state, even by the use of force, mounted daily. Every day Carr’s desk was inundated by letters and telegrams, virtually all apprehensive and often openly racist. “We are protesting,” a Mr. and Mrs. Cline wrote, “California’s Asiatic, almond-eyed, yellow bellied, sneaking skunks.”

Governor Carr kept his silence for a time, then scheduled another radio address designed to assuage fears and inject a note of calm and tolerance. The speech would be carried statewide and was scheduled for a Saturday evening to ensure a maximum listening audience. Carr basically said that Colorado would do its part in the general war effort. If the U.S. government required that some Japanese Americans live in the mountain state, so be it. “Colorado will do her part and more.”

The only part of his address that was negative, at least in hindsight, was his acceptance that the Pearl Harbor attack was greatly aided by “fifth columnist” saboteurs and that the West Coast might indeed harbor additional subversives. The idea of spies, saboteurs, and enemy terrorists was an obsession of the time, and as a man of his time, Carr shared it. The reports of massive sabotage were later proved to be utterly false.

Ralph Carr was more true to form when he said he wanted to “speak a word on behalf of the loyal German, Italian, and Japanese citizens who must not suffer for all the activities and animosities of others. In Colorado there are thousands of men and women and children—in the nation there are millions of them—who by reason of blood only are regarded by some people as unfriendly.”

Warming to his subject, Carr continued: “They are as loyal Americans as you or I. Many … are American citizens, with no connection with or feeling of loyalty toward the customs and philosophies of Italy, Japan, and Germany. It is not fair for the rest of us to segregate the people from one or two or three nations and to brand them as unpatriotic or disloyal regardless.”

Some Colorado newspapers applauded his stand, but most were negative. In one paper an editorial cartoon labeled Carr “Mr. Softy” and showed him smiling benignly at three kids representing Germany, Italy and Japan. The “kids” are delinquents at best; “Japan” has a gun, “Italy” a knife. The “kids” also have labels on their clothes, like “Enemy Aliens,” “sabotage,” and “Map of U.S. Defense.” And, sadly, the people of Colorado mainly agreed with the cartoon, not the governor.

His radio speech was noteworthy, but Carr’s most shining moment was when he confronted an angry group of white Coloradan farmers in person. The towns of Swink, La Junta, and Rocky Ford were located in the Lower Arkansas Valley, and they were increasingly unhappy when Japanese Americans started to come into the area. There were tumultuous town meetings, and Carr was warned that “open violence” might erupt at any time.

Governor Carr’s response was to meet the problem head on by personally traveling to the affected area. When he went to the podium to speak at a farmers’ meeting, the tension was palpable, but he was not going backtrack one inch.

“An American citizen of Japanese descent,” he thundered, “has the same rights as any other citizen…. If you harm them, you must first harm me. I was brought up in a small town where I know the shame and dishonor of race hatred. I grew to despise it because it threatened the happiness of you and you and you.” As Carr spoke the last sentence he dramatically pointed to three farmers in the crowd. “In Colorado,” he added, “[they] will have full protection.”

The crowd let him have his say, but few if any were won over. A group of Lower Arkansas residents later sent Carr a sarcastic telegram. “Rush 250 doses of Jap soothing salve to Swink,” ran the missive, “Last Thursday [your speech] did not take.” But the speech has stood the test of time in clearly enunciating American ideals.

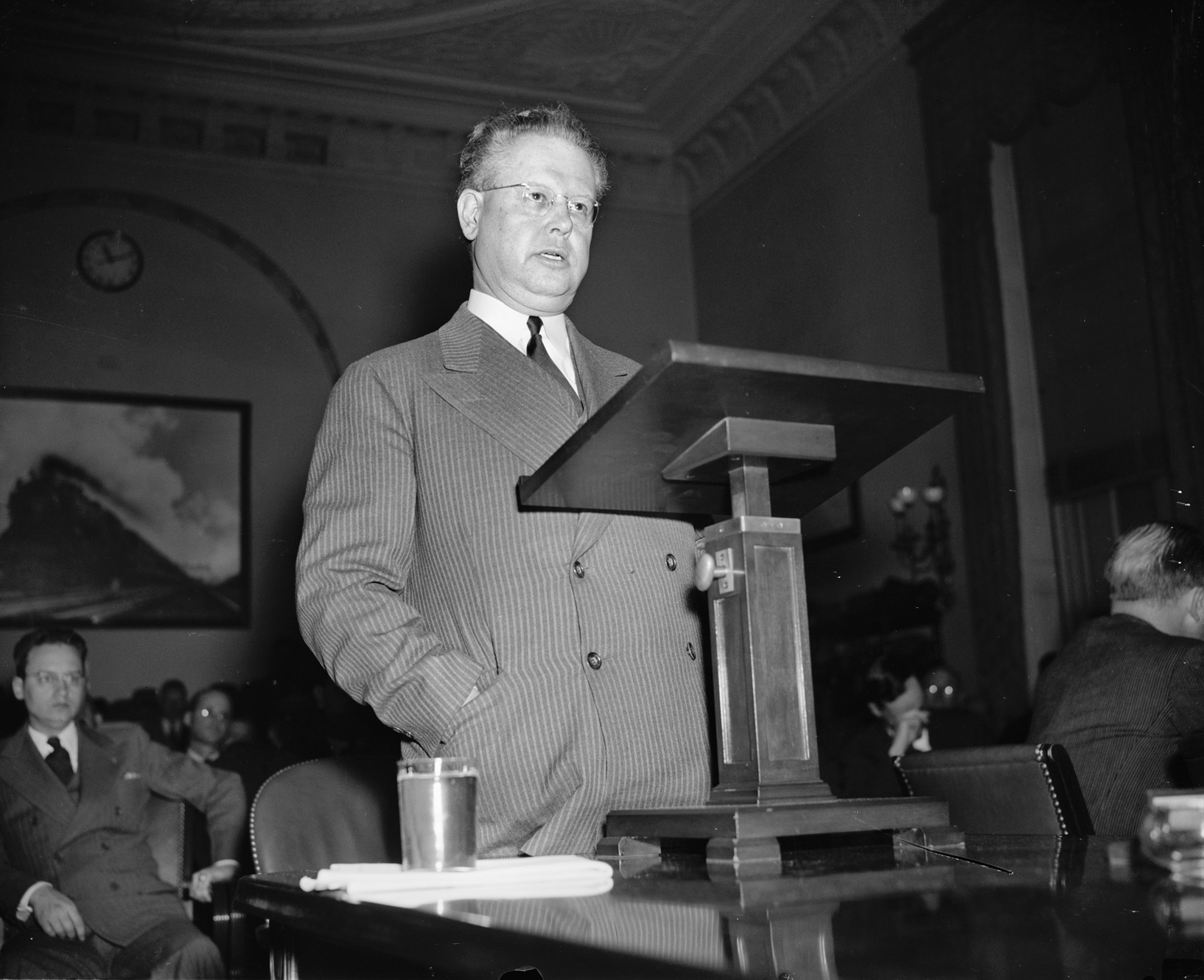

On April 7, 1942, Milton Eisenhower, director of the War Relocation Authority, held a meeting with western state governors, attorneys general, and other officials at Salt Lake City. The conference was an important one because it was going to determine the ultimate fate of the 112,000 or so Japanese Americans who had not moved during the “voluntary” period. Ten states were represented, including Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Washington, Oregon, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, New Mexico, and Nevada.

Eisenhower was the younger brother of the soon-to-be-famous General Dwight D. Eisenhower, but he had a distinguished New Deal career in his own right. Director Eisenhower was emphatically not in favor of Japanese American incarceration and did what he could to avoid establishing concentration camps. Before the state governors meeting he had suggested that only Japanese American men be temporarily removed, letting families stay in their homes and wives or female relatives run businesses if needed. The idea was quickly shot down.

Casting about for a solution, Eisenhower thought that temporary camps, not prisons, could be established for the Japanese Americans. They would live in these temporary encampments but find employment in nearby communities. The model he envisioned was based on the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) working camps in the 1930s. Japanese Americans could help in agriculture, for example, where there were labor shortages due to men being drafted into the military.

Milton Eisenhower expected some opposition, but he was totally unprepared for the reaction he received when he tried to discuss the matter with the governors. Eisenhower was pummeled with a firestorm of racist invective against the Japanese Americans. Each governor, with one exception, Ralph Carr, seemed determined to outdo each other in expressing the vilest forms of bigotry. Many were literally yelling at the top of their voices.

Arizona Governor Sidney Osborne wanted all Japanese Americans in concentration camps. “Concentration camps” was the term he preferred because apparently it conveyed the harshness he wanted meted out to the Japanese Americans. No soothing euphemisms like “relocation centers” for him! Idaho Governor Chase Clark was worried that, after the war, the temporary Japanese American communities might become permanent. “I don’t want 10,000 Japs to be located in Idaho!” he declared. Idaho Attorney General Bert Miller concurred, adding, “We want to keep this a white man’s country.”

But probably the worst remarks came from Wyoming Governor Nels Smith. “People in my state don’t like Orientals,” he explained. Indeed, if any Japanese Americans tried to buy land in Wyoming “there would be Japs hanging from every pine tree.”

Govenor Carr predictably welcomed any evacuees, but he was in the minority. The message was clear: the Japanese Americans would only be accepted if they were locked up in prison camps, placed securely behind barbed wire and under guard. Eisenhower, shell shocked from his reception, was forced to recommend prison camps to Congress. There was simply no alternative under the circumstances.

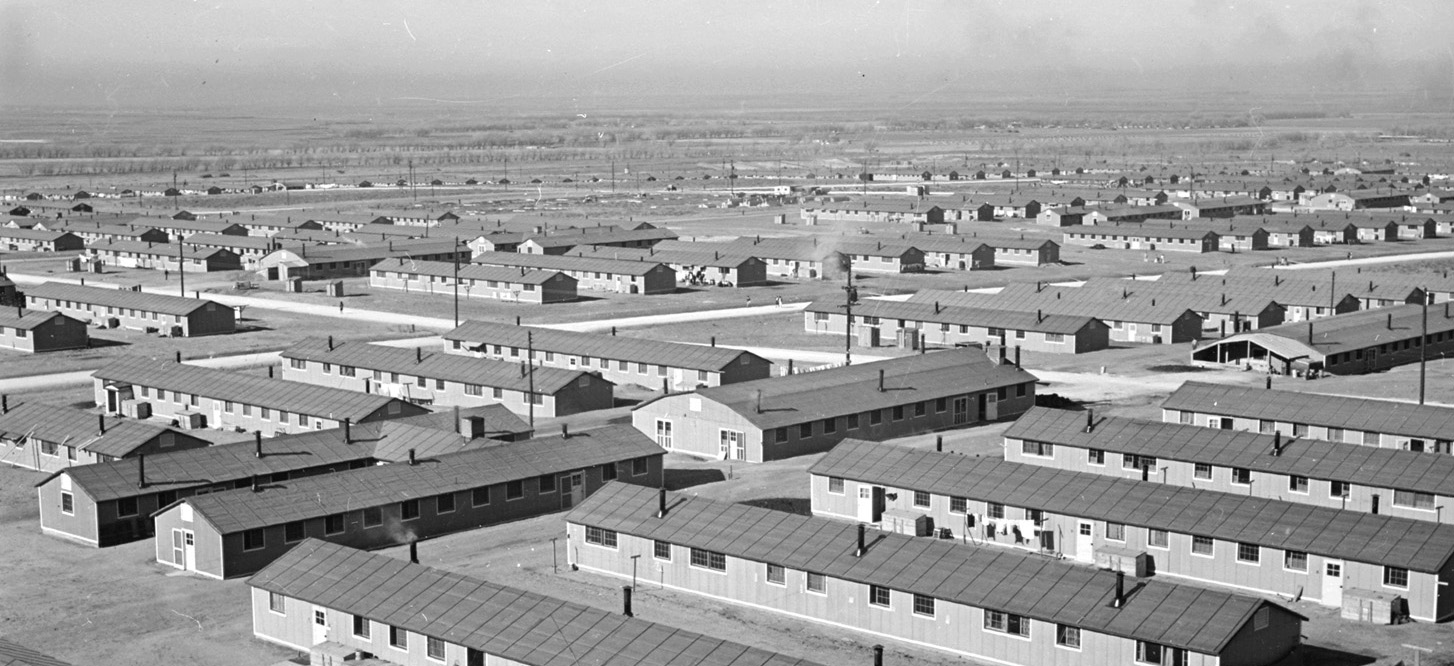

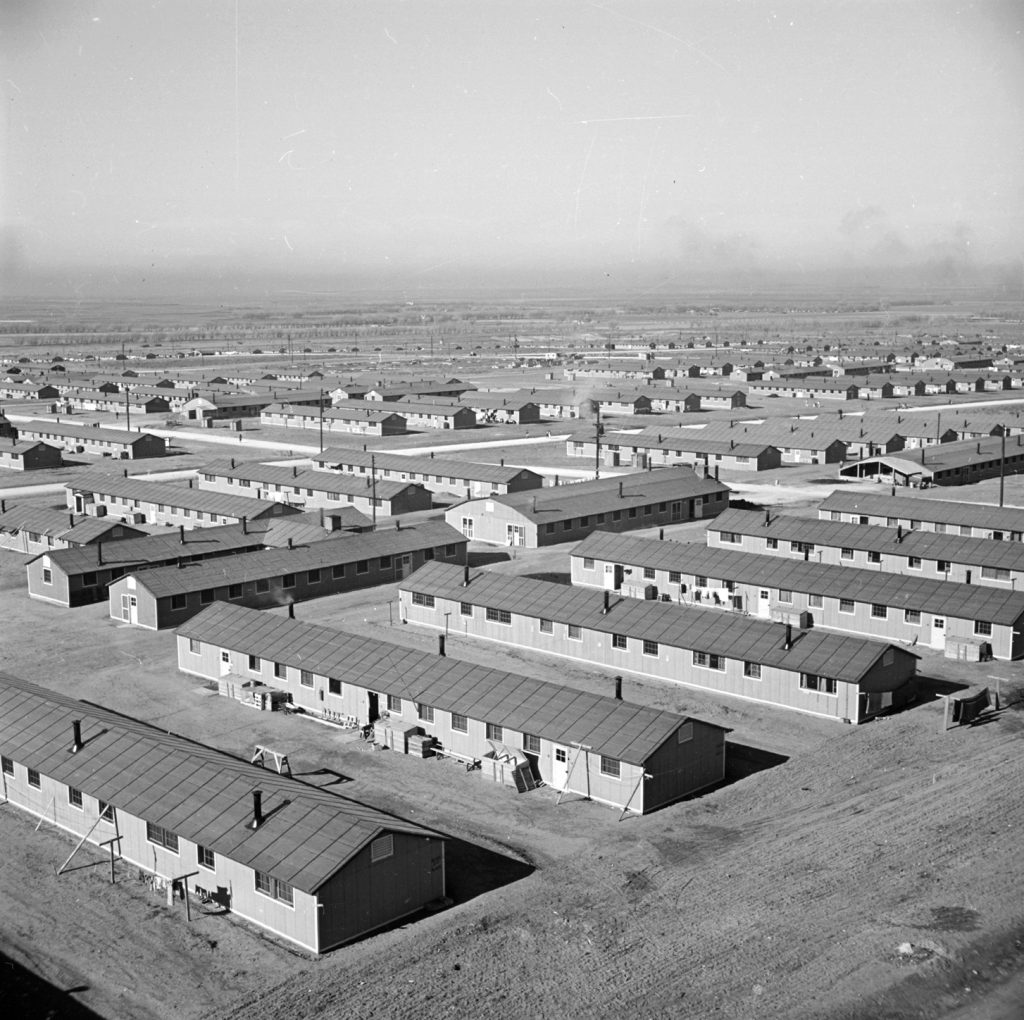

Eventually 10 permanent concentration camps were established throughout the country. The most famous, at least in retrospect, were those in California, Tule Lake, and Manzanar. But Colorado also had a concentration camp, the formally named Granada Relocation Center. Located in southeastern Colorado, about 15 miles from the Kansas border, Granada was nicknamed Amache. The camp was opened in August 1942, and though Carr left office in early 1943, something of his tolerant spirit seems to have rubbed off on both camp administrators and local white residents.

Amache was unique in that it was only one mile from the town of Granada, well within walking distance. Permission was given for Japanese American inmates to visit the town, which they did. After some initial tension, most Granada businessmen came to appreciate the Japanese Americans as customers. Shopping around town or visiting the local soda fountain were frequent occurrences and boosted inmate morale.

The Japanese Americans found the land was generally arid, but with irrigation water from the nearby Arkansas River the high plains bloomed. In 1943 alone inmate farmers produced four million pounds of vegetables. Even more amazingly, prisoner Frank Tsuchiya obtained his release and opened the Granada Fish Market in town. His business was very successful; he even brought in sashimi-grade fish from Los Angeles.

To show his continued support for Japanese Americans, Carr wanted to hire an inmate woman to be his employee. The position to be filled was “house girl.” The term would be considered racist, demeaning, and perhaps even sexist today, but in 1943 it simply meant housekeeper. It was to be a salaried job; the governor was determined to put his “money where his mouth was.”

Wakako Domoto was the Japanese American woman who was hired as Carr’s housekeeper. A Nisei, American born, 31 years old, she hailed from Oakland, California, and had attended Stanford University for two years. Her father, Kanetaro Domoto, was the co-owner with his brother of the largest nursery in the Golden State. She hesitated about accepting the job; few women left Amache camp, and there was a very real fear of lynching or other violence.

Domoto accepted and nervously boarded a train for Denver. When she arrived at the Denver railroad station the governor himself was there to safely escort her to his home. Besides room, board, and a regular salary, Carr enrolled her at the Emily Griffith Opportunity School at his own expense.

Ralph Carr’s courageous stand came at a high political price. When he ran for U.S. senator he was defeated by the leading Democrat, Edwin “Big Ed” Johnson. Johnson, who served as governor before Carr, had called out the Colorado National Guard in 1936 and tried to seal the border with New Mexico. The main reason was to keep out Mexican migrant workers and “indigents” and prevent them from entering the state. Johnson’s racist and xenophobic attitudes resonated with Colorado voters in 1942.

But after the war Coloradans realized that Carr had been right, and in 1950 he was on the brink of a comeback. He ran for governor that year, but after winning the Republican nomination he died of a heart attack. He was 62. After his premature death he was forgotten for decades, but there has been a renewed interest in his life and career. Colorado is proud of its native son, and highways and buildings have been named in his honor. A bust and memorial to Governor Carr were dedicated in Denver. In a time of darkness, he was a shining example of the best in the American character.

Author Eric Niderost is a frequent contributor to WWII History on a variety of topics. He resides in Union City, California, where he is also a college professor.