By Mark Carlson

Today, every U.S. naval aviator who straps into a cockpit owes a debt to a man they never met and few have even heard of—Vice Adm. Frederick M. Trapnell, the “godfather of modern naval aviation.” Every fighter, attack aircraft, troop carrier, transport, helicopter and aerial surveillance plane in the Navy inventory for the last 60 years has been tested, evaluated and improved by the dedicated graduates of the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School at Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland. There, hundreds of men and women are the direct inheritors of the legacy that Trapnell began when he first pinned on his wings of gold in 1927.

Born in July 1902, Frederick Mackay Trapnell displayed a love of the sea and ships at an early age. An appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy honed his gift for engineering, a trait that served him well all his life. Serving on battleships and cruisers after his graduation in 1923, the young officer earned the respect of the enlisted men through his willingness to work alongside them and get his hands dirty.

Fascinated by the Navy’s early scout biplanes, Trapnell applied for aviation training at NAS Pensacola in Florida. He displayed a natural ability as a pilot and took great pains to familiarize himself with every airplane he flew. When he earned his wings in March 1927, Trapnell was unknowingly situated on the threshold of the most dynamic generation in aviation history.

Lieutenant Trapnell was assigned to the pioneering Torpedo Squadron 1 of the newly commissioned aircraft carrier Lexington, flying the three-seater Martin T3M biplane, the Navy’s first torpedo bomber. In 1928 Lexington joined fleet exercises off Hawaii, where Trapnell began to fly and evaluate the current crop of bombers. He then joined the Navy’s first officially designated fighter squadron, VB-1 (later VF-5). The “Red Rippers” would be the longest-serving fighter squadron in the Navy. They flew the nimble and rakish Curtiss F6C Hawk, a carrier-capable variant of the Army’s P-1 Hawk. Trapnell loved the agile biplane.

Under the tutelage of fellow pilot and friend Lt. Matthias Gardner, Trapnell practiced the new doctrine of coordinated air attacks with dive bombers, torpedo planes and fighters. Still, he had to prove his skills as a wingman with a more experienced leader, Lt. Jimmy Barner. Virtually every “nugget” pilot required several sessions to become proficient at close-quarters maneuvering and aerobatics. But when Trapnell landed at NAS San Diego after his first trial, Barner simply shook his hand and said, “I’m glad to welcome you aboard.”

In early 1929 the Pacific Fleet conducted exercises in the Panama Canal Zone, recognized as a prime target for any oceangoing belligerent power. Trapnell and the other Rippers flew almost daily, fine-tuning tactics that would shape the Navy’s future. He flew the new Boeing F4B from August to December of that year. During a test flight over Kearny Mesa north of San Diego, he joined the “Caterpillar Club”—the elite fraternity of pilots who had to parachute in an emergency—when an F4B’s fuel line caught fire and he bailed out.

In those early days a manufacturer rarely provided details on the performance envelope of an aircraft, so it was up to the Navy to assess its strengths and weaknesses. Assigned to fly recently repaired planes or new models, Trapnell displayed an knack for recognizing design flaws and making astute recommendations to remedy the problem. It would be a recurring theme during his career.

In December 1929 Lieutenant Barner had Trapnell assigned to the Navy’s Flight Test Section at NAS Anacostia in Washington, D.C. There Trapnell found his true calling. His clear and concise notes and performance data stemmed directly from his Annapolis work on hydrodynamics. He was able to fly every single plane on the field, greatly adding to his personal understanding of what qualities the best fighters and bombers possessed.

“Trapnell was the sharpest student of aerodynamics and flight testing that we had,” test pilot Robert Pine wrote. “I believe he is the best pilot and probably the best test pilot I have ever been associated with.”

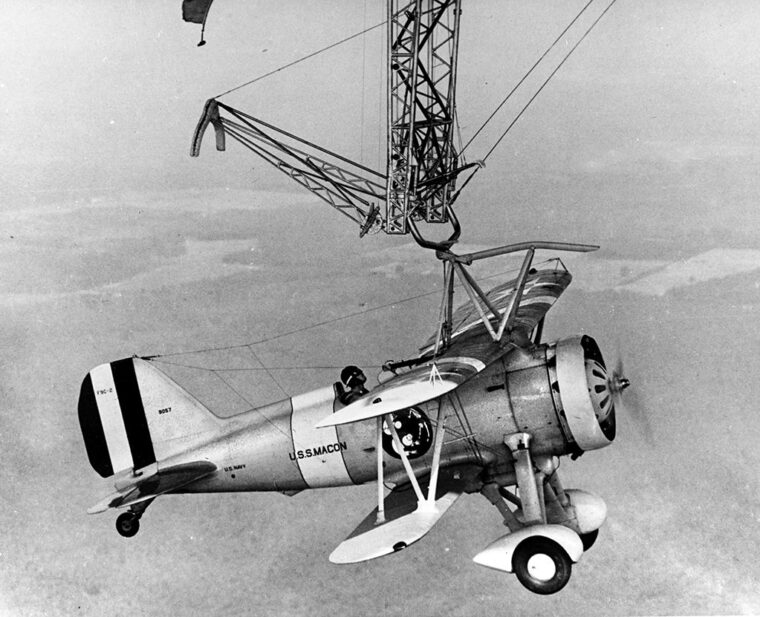

In the early 1930s the Navy, particularly Bureau of Aeronautics chief Admiral William Moffett, was dedicated to the dirigible for long-range fleet reconnaissance. In 1931 the USS Akron, the world’s most advanced airship, was nearing completion at the Goodyear-Zeppelin hangar in Akron, Ohio. The Akron was designed to carry small biplane fighters in a bay in the ship’s belly. Trapnell evaluated the tiny Curtiss F9C-2 Sparrowhawk, working with Akron’s Heavier-Than-Air (HTA) unit to develop procedures and tactics to make the vulnerable airship into a long-range scout aircraft carrier.

A complicated trapeze system lowered the Sparrowhawk into the airstream, from which the pilot would then release and fly off on a mission. Disengaging from and hooking onto the trapeze required deft control and could only be accomplished in ideal weather. When Akron was commissioned in late 1931, the trapeze system was still seriously flawed. Trapnell designed a simpler and more automated system that stabilized the fighter without the pilot having to do it manually. The new system was successful, and in a few months Akron and sister ship Macon were ready.

But there was still controversy as to how the airships should be employed in warfare. “A few of the ship’s officers and I of the enlightened heads at BuAer [Bureau of Aeronautics] thought the airship should hang back at the [sight of the] enemy and let her airplanes do the scouting,” said Trapnell.

In any case, the airships’ moment in the sun would be brief. On April 3, 1933, Rear Admiral Moffett was on board Akron for a demonstration flight of the mid-Atlantic coast in which three Sparrowhawks were to fly out and hook up. Trapnell was tasked with flying Akron’s single two-seater “running boat” from NAS Lakehurst in New Jersey to the airship as a ferry plane for the admiral. But the weather delayed takeoff clearance. As the hours passed the weather off the Jersey coast turned vicious, and Trapnell became worried. Many of the 76 men on board the airship were his friends.

As dawn broke the following day the cruel truth emerged: Akron had crashed at sea, killing Moffett and all but three of his crew. At the time it was the worst air disaster in history. Trapnell had come within a whisker of being on board when Akron took its fatal plunge into the stormy Atlantic.

Named head of the HTA unit, Trapnell worked on Macon out of NAS Moffett Field in Sunnyvale, California, After the Akron disaster, the pressure was on to validate what proved to be a flawed concept. In 1935 Macon crashed, ending the Navy’s experiment with giant airships. By then the Consolidated P2Y, the first successful long-range flying boat, was proving capable of doing the airships’ job of patrolling the seas with far less vulnerability.

In 1936 Trapnell was assigned to VP-10 in Hawaii, where he helped develop the Navy’s search and patrol strategies. He commanded a successful squadron deployment of new Consolidated PBY Catalinas from California to Hawaii in January 1938, setting a record of 20.5 hours for the 2,550-mile flight.

Trapnell was never out of the sky for long. He flew, evaluated and made recommendations for nearly every prototype and production plane in the Navy and Marine Corps inventory. The early torpedo and dive bombers were as much an exercise in theory as in aeronautical technology. The Navy’s Northrop XBT-1 monoplane dive bomber pioneered the use of split dive brakes. It was followed by the Vought SB2U-1 Vindicator, which, like its predecessor, was obsolete by the beginning of World War II. Only when the sturdy Douglas SBD Dauntless took to the skies did America field a truly effective dive bomber for carrier warfare.

After the smoke cleared over the shattered battle fleet at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, it was obvious that the outcome of the Pacific War hinged heavily on aircraft carriers. At Anacostia, Trapnell was eager to get into combat but the Navy believed his engineering skills and experience were too valuable to lose. Working 12-hour days six and seven days a week, he strove to perfect the Navy’s next generation of warplanes.

Trapnell flew them all, including the Grumman F4F Wildcat and Brewster F2A Buffalo fighters. But it was with the radical and tricky Vought F4U Corsair that he really made a significant contribution to the future of Navy fighters.

The Corsair’s inverted gull wings, long nose and powerful engine causeed major problems. After severe delays and accidents, Trapnell went to the Vought plant in Stratford, Connecticut, to test the new fighter. He quickly saw the Corsair’s potential, taking it to 402 mph—a world record for production piston-engine fighters. By November he was testing the Corsair at Anacostia, helping Vought and the Navy iron out the design of what became one of the most successful fighters in the Pacific.

By 1940 Trapnell had logged more than 3,800 hours in 80 types of aircraft. At his suggestion, the Navy collaborated with manufacturers in early flight testing—a radical concept that helped many warplanes quickly enter production.

In mid-1942, with the Pacific War in full fury, Trapnell’s skill as a flight test engineer gave him the opportunity to fly the most feared Japanese fighter, the Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero. During the Japanese attack on the Aleutians in the June Midway campaign, Zero pilot Tadayoshi Koga was forced down into the tundra on Akutan Island. Koga was killed but his Zero was nearly intact. The Navy recovered it and took it to San Diego. After being repaired it was turned over to Trapnell, by then a full commander, to assess its capabilities and limitations.

With Trapnell flying a new Corsair and Lt. Cmdr. Eddie Sanders in the Zero, the two pilots dueled off San Diego. They shattered the myth that it could fly rings around anything in the sky and proved that the Zero did have serious shortcomings, notably its high-speed and high-altitude performance. In his report, Trapnell wrote, “The Zero was faster and had a faster climb rate than the Wildcat, but was more vulnerable and less maneuverable at high speed.”

Meanwhile, Trapnell read Pacific combat reports and made recommendations to improve the next generation of fighters, including the Grumman F6F Hellcat. “He came to the factory and flew the prototype F6F,” said Leroy Grumman. “It suited him, as I remember, except for the longitudinal stability—he wanted more of that. We built it in, and rushed into production without a Navy certificate on the model—we relied on Trapnell’s opinion. His test flight took less than three hours. I’m not sure that we ever got an official O.K. on the Hellcat design. I think it finally came through after V-J Day. By that time Hellcats had shot down 5,155 Japanese planes—and that’s over half of the Navy’s total bag for the war.”

Trapnell was still itching to get out to the Pacific, finally making it into the war in the spring of 1944 as executive officer of the escort carrier Breton, which was ferrying planes to the war zone from the West Coast. He earned a Bronze Star for developing a method for Hellcats to take off from a carrier deck in just 190 feet, thus increasing the number of planes that could be carried on the small ships.

After participating in the invasion of Saipan, Trapnell was assigned as chief of staff to Rear Adm. Arthur Radford, whom he had known since the 1930s, on the flagship Yorktown in Task Group 38.1. There he played a role in the huge campaigns in the Carolines and later the Philippines. Trapnell witnessed kamikaze attacks and in December survived the fury of Typhoon Cobra, the worst tropical storm of the war. He coordinated every aspect of Yorktown’s air operations, from fuel to ordnance, targets and after-action reports.

Trapnell continued testing new aircraft after the war. He felt that “full spectrum testing” within their operational environment was the best way to evaluate new designs. In June 1943 the Flight Test Section had moved from Anacostia to NAS Patuxent River. There the Navy put each new prototype and production plane through rigorous tests of speed, rate of climb, high-altitude performance, maneuverability, carrier suitability and several other criteria. Each plane was evaluated on its armament, electronics and maintenance requirements.

Naval aviation changed radically duringTrapnell’s career. The speed and power of the new jets meant carrier operations needed major refinement. Reinforced flight decks and new approach, landing and launch procedures were developed. The pressure to put jets on carriers in a reasonable schedule reinforced the need for early testing.

Vice Admiral Radford, now deputy chief of naval operations for air, tagged Trapnell to head up the new Naval Air Test Center (NATC) as coordinator. Trapnell would have full creative control of the center, including the selection and training of the new crop of naval test pilots. By February 1947 he had begun a vigorous recruiting campaign to fill out the ranks with the most talented, experienced and educated aviators he could find. The learning curve was steep, as the early jets were unforgiving of errors. They required test pilots who also had the engineering background to understand the finer points of each testing program.

By the early 1950s the NATC was turning out dozens of new test pilots eager to make their mark evaluating the hottest new planes from Grumman, Vought, McDonnell, Douglas and a dozen other companies. Some of the new planes, such as the Convair XF2Y Sea Dart and Vought XF7U Cutlass, proved to be colossal failures, but others, like the Grumman F9F Panther, Vought F-8 Crusader and Douglas A-4 Skyhawk, took the Navy into the jet age. Trapnell oversaw every test program and recommendation with the same zeal and skill he had displayed in the past. He also played a small role in the testing of transonic and supersonic research aircraft, getting a chance to fly the Douglas D-558 Skystreak to a speed of Mach 0.86.

In 1950 Trapnell was granted his fondest wish, command of an aircraft carrier. As captain of Coral Sea, he would miss the highly dynamic world of flight testing but was back in his element. Coral Sea was the first U.S. carrier to deploy with jets and the first to carry a plane that Trapnell personally considered the best, the McDonnell F2H Banshee. During his time on the carrier, he developed the concept of “double-line” launching, greatly increasing the carrier’s ability to rapidly deploy aircraft.

Trapnell was 49 when he was diagnosed with a heart ailment in January 1952 ending his flying career. He had flown 6,272 hours during 5,012 flights in 162 airplane types. After a heart attack, he retired in September 1952 with the rank of vice admiral. In 1957 the Society of Experimental Test Pilots elected him one of its first honorary fellows.

A year after his death in 1975, the airfield at NAS Pax River was officially named Trapnell Field. In 1986, he was posthumously inducted into the U.S. Naval Aviation Hall of Honor.

Trapnell’s legacy is evident in the past, present and future of naval aviation—from the earth to the moon. All the Navy and Marine aviators who joined NASA in the late 1950s and 1960s were NATC graduates, including Alan Shepard, John Glenn, Wally Schirra, James Lovell, Alan Bean, Dick Gordon, Pete Conrad and John Young.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments