By Robert L. Durham

The dense formation that constituted the Army of the Potomac’s Black Hat Brigade formed up on Joseph Poffenberger’s farm at dawn on September 17, 1862. They then dutifully tramped south through the gray mist of the damp morning as the crump of artillery and rattle of musketry increased in intensity in the farm fields and woods along Hagerstown Pike near the whitewashed Dunker Church.

“You’re in open range of rebel batteries,” Brig. Gen. Abner Doubleday informed brigade commander Brig. Gen. John Gibbon as his men prepared to engage the enemy. Confederate shells and case shot exploded on and around them as they advanced. The storm of iron sent men and equipment flying through the air. The horrific experience sorely tested the discipline of the Wisconsin and Indiana troops who made up the brigade, but they had fought admirably at Brawner’s Farm and South Mountain, and possessed the grit necessary to withstand the shelling.

The 6th Wisconsin spearheaded the brigade’s advance through David R. Miller’s farm on the east side of the pike toward his sprawling 30-acre cornfield, led by Lt. Col. Edward Bragg. The mature corn was as tall as the soldiers who would fight their way through it that morning. Rebel skirmishers fell back steadily before the advance of a sea of blue-coated soldiers.

The regiment went into action straddling Hagerstown Pike, with its soldiers fighting on both sides. The companies on the 6th Wisconsin’s left cautiously entered the northwest quadrant of the cornfield. A heavy fire erupted from Confederates in the cornfield, as well as in the West Woods. Rebel volleys knocked men down, splintered the fences on both sides of the turnpike, and sheared off stalks of corn. The stout-hearted men of the 6th Wisconsin returned the fire, but they needed help.

The storm of Confederate fire directed at the men of the Black Hat Brigade marked the beginning of a long and bloody fight that would eclipse the intensity of their previous battles. The brigade’s story remains one of the most compelling sagas of the battle that unfolded in the rolling fields that day around Sharpsburg, Maryland

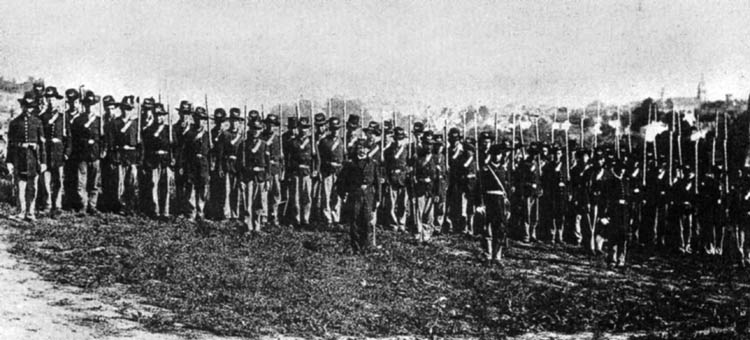

The four infantry regiments that constituted Gibbon’s brigade at Antietam were the 19th Indiana and the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin. The regiments had the distinction of being the only units in the Army of the Potomac from the Midwest, except for those from Ohio. Gibbon’s four regiments were nicknamed the Black Hat Brigade due to their distinctive tall Hardee hats. In addition to their hats, their dress uniforms consisted of long frock coats, white gaiters, and white gloves. Gibbon, who was a veteran officer of the pre-war U.S. Army, had selected these items for his soldiers because he believed that having a distinctive dress would lay the foundation for developing an esprit de corps.

Although the Black Hat Brigade had been activated in Washington, D.C., in October 1861, it did not participate in the Peninsula Campaign of spring 1862. The brigade underwent its baptism of fire while serving in Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia during the Battle of Second Manassas. Their first chance to prove their worth came in a bloody affair at Brawner’s Farm against Maj. Gen. Thomas Jackson’s troops on August 28, 1862. In that two-hour clash, which marked the beginning of the Battle of Second Manassas, the four regiments held their ground despite being heavily outnumbered. Major General Philip Kearny later paid the brigade a great compliment by observing that it was one of the few units that had managed to maintain their cohesion throughout the bungled three-day battle that ended in a Confederate victory.

Shortly after Second Manassas, Maj. Gen. Robert E. Lee led the Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland, pursued by the Army of the Potomac, now commanded by a reinstated Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who replaced Pope after the second debacle at Manassas.

Lee’s army crossed the Potomac River on September 5 and assembled near Frederick, Maryland. On September 10, Lee issued Special Orders 191 to his generals, outlining a plan for capturing Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, which was garrisoned by 10,000 Union troops. The orders split the army into four parts, three of which would concentrate against the Federal arsenal that lay astride Lee’s lines of communication into Virginia. The capture of the arsenal was entrusted to Stonewall Jackson. While Jackson’s columns besieged Harper’s Ferry, Lee and his I Corps commander, Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, would wait at Hagerstown, Maryland, for Jackson to join them once he had captured the isolated Union outpost.

Lee was banking on South Mountain, the extension of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Maryland, to mask his movements. Once his army had reunited, Lee planned to manuever against McClellan’s army. To prevent the Federals from making a rapid passage over South Mountain, Lee detached Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill’s division to defend Turner’s Gap, where the National Road crossed the 2,100-foot mountain. A thin screen of infantry and cavalry defended Crampton’s Gap six miles to the south. Hill distributed his five brigades to hold Turner’s Gap and nearby Fox’s Gap, which he only became aware of during his inspection of the ground he had to defend.

Unfortunately for Lee, one of his officers dropped a copy of the orders on the ground at a Confederate bivouac at Frederick, Maryland. When the Union army marched through the area, a Union corporal found the orders and forwarded them to McClellan, who received them on September 13. After reviewing the orders, McClellan saw a golden opportunity to destroy the Army of Northern Virginia one section at a time. McClellan gleefully shared the news with Lincoln. “I think Lee has made a gross mistake, and that he will be severely punished for it,” wrote McClellan. “I have all of the plans of the Rebels and will catch them in their trap.”

The Union Army lumbered west towards South Mountain on September 14. For his assault on South Mountain, McClellan had divided his army into three parts. Major General Ambrose Burnside on the right wing would force Turner’s Gap, and Maj. Gen. William Franklin on the left would clear Crampton’s Gap, while Maj. Gen. Edwin Sumner would command the Union reserve. Burnside had the I and IX Corps, Franklin had the IV and VI Corps, and Sumner controlled the II, V, and XII Corps.

The soldiers of Gibbon’s Black Hat Brigade, which was the 4th Brigade of Brig. Gen. John Hatch’s division in Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s I Corps, went into action at South Mountain on the extreme left of the I Corps line.

Hooker ordered Gibbon to lead his hard-charging Midwesterners straight up the National Road and create a convincing diversionary attack while the bulk of the I Corps struck southward to turn the Confederate north flank. The main force of the I Corps had orders to gain a secondary road that led from the hamlet of Frostown to Hill’s headquarters at the Mountain House in the center of the gap. To secure the road, the flanking troops would have to attack up rugged spurs that protruded from the mountain on each side of the defile.

Facing the 1,300 muskets of the Black Hat Brigade was Brig. Gen. Alfred Colquitt’s brigade, which was composed of four Georgia regiments and one Alabama regiment. The Midwesterners bided their time for two hours under fire from Confederate cannon posted in the gap while the rest of Hatch’s division moved into position for their flank attack.

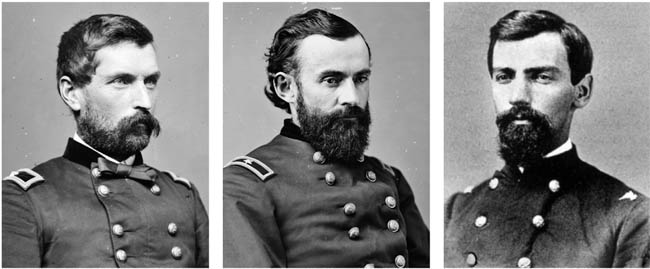

Hooker ordered Gibbon to advance at 5:00 PM. Gibbon had his regiments in a line astride the pike. North of the National Road, Captain John Callis’ 7th Wisconsin led the attack with Bragg’s 6th Wisconsin in support, while south of the road, Lt. Col. Alois Bachman’s 19th Indiana led the assault with Colonel Lucius Fairchild’s 2nd Wisconsin in support. Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, Gibbon’s old battery in the regular army, unlimbered on the pike and began shelling the Confederates. The Rebels were well concealed in the heavily forested, broken terrain. They held strong positions behind fences, logs, trees, and boulders. It was “an ugly place to attack,” noted Lieutenant Frank Haskell of Gibbon’s staff.

As blue-clad skirmishers engaged their counterparts, Meredith sent a request for the battery to shell Confederate sharpshooters who were picking off his troops from the two-story stone house owned by D. Beachley situated next to the road. When the Yankee gunners sent a shell into the second floor, the Rebels inside hurriedly exited the building.

The two regiments on the south side of the road initially faced the greatest resistance, but that changed when Callis’ men emerged from a cornfield and encountered deadly accurate fire from Confederate skirmishers posted behind a stone wall. Rebel skirmishers seemed to be everywhere, and the men of the 7th Wisconsin were soon taking fire from three directions. Nevertheless, they held their ground.

Colquitt held back the bulk of his brigade, relying on skirmishers and open formations to resist the Federal brigade arrayed against him. The men of the Black Hat Brigade pressed forward in the face of well-aimed Confederate fire, but the firing did not deter the determined Midwesterners. “[The men] hurried over the rough and stony field with the utmost zeal,” wrote Major Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin. “There was neither hesitation nor confusion.” Bragg did his best to try to turn Colquitt’s northern flank. Hill’s troops were reinforced at dusk by elements of Longstreet’s corps, which had made a forced march from Hagerstown. The onset of darkness brought an end to the day’s fighting, and the Rebels withdrew from South Mountain during the night. The Confederates reassembled on the high ground west of Antietam Creek around from the town of Sharpsburg. Colquitt reported that he suffered 110 killed and wounded, while Gibbon’s losses amounted to 37 killed, 251 wounded, and 30 missing.

McClellan had observed though his field glasses the tenacious fighting of Gibbon’s Midwestern men. When Hooker arrived to confer with McClellan regarding additional orders, the army commander purportedly asked “Fighting Joe” to identify the troops he had been observing. “[Those are] General Gibbon’s brigade of Western men,” Hooker replied. “They must be made of iron,” said McClellan. “By the Eternal, they are iron! If you had seen them at Bull Run, as I did, you would know them to be iron.” Hooker was soon referring to the unit as his Iron Brigade.

That McClellan bestowed the name upon them was mentioned in letters that soldiers of the brigade sent to friends and family back home. “General McClellan has given us the name of the Iron Brigade,” wrote Private Hugh Perkins in a letter to a friend date September 24. In addition, correspondents of northern newspapers covering the battle began using the nickname. “[Gibbon’s] brigade has done some of the hardest and best fighting in the service,” stated an article in the Cincinnati Daily Commercial. “It has been justly termed the Iron Brigade of the West.”

The brigade, along with the rest of the Union Army, set out for Boonsboro, Maryland, on September 15, where the townsfolk cheered them. “They swung their hats and laughed and cried without regard for appearances,” wrote Dawes. From Boonsboro, Hooker’s corps marched three and a half miles to Keedysville. Confederate cannon posted on the high ground before Sharpsburg on the west side of Antietam Creek shelled them. Gibbon’s troops bivouacked in a ravine, where they hoped to escape the artillery fire.

Late in the day on September 16, McClellan ordered Hooker’s I Corps to cross Antietam Creek and probe the enemy positions. The troops tramped across the Upper Bridge, reaching their assigned position at 9:00 PM. The brigade formed into columns with loaded rifles near the North Woods on Joseph Poffenberger’s farm for their advance the following morning.

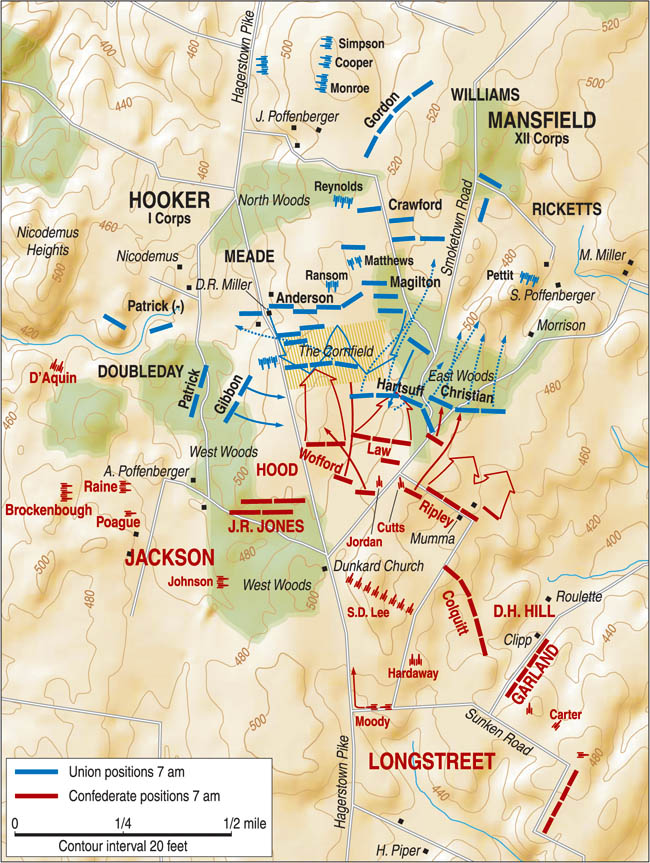

When Hatch was seriously wounded at Turner’s Gap, Brig. Gen. Abner Doubleday had assumed command of Hooker’s 1st Division. Doubleday now rode along his lines just before dawn, adjusting the position of his troops to protect them as best as possible from Confederate guns to the south. Hooker, to whom McClellan had given the honor of spearheading the Union attack, planned to advance south on both sides of Hagerstown Pike towards the Dunker Church. Doubleday’s division held a key position on the Union’s extreme right flank. To its east, Brig. Gen. James B. Ricketts had orders to send his division through D.R. Miller’s cornfield and the East Woods. Moving in the center was Brig. Gen. George G. Meade’s division.

Major General Jeb Stuart, who commanded the Confederate cavalry, had placed four batteries on Nicodemus Heights to contest Hooker’s advance. The Rebel gunners had a clear field of fire over the farmland across which Hooker’s troops would be advancing. Once Hooker’s attack was underway, Colonel Stephen D. Lee’s artillery battalion, which was deployed on high ground east of the Dunker Church, also began shelling Hooker’s troops.

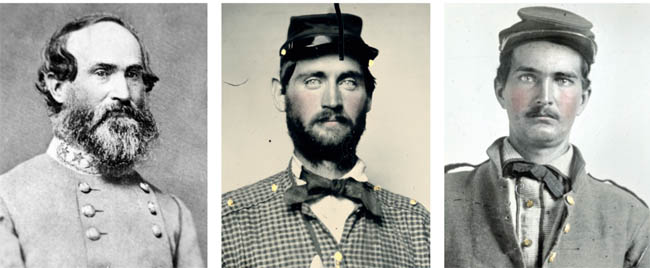

Two of Stonewall Jackson’s four divisions defended the West Woods and Miller’s cornfield. The West Woods measured 300 yards wide at its southern end, but tapered to a width of 200 yards at its northern end. On the extreme Confederate left in the West Woods was Jackson’s old division, led by Brig. Gen. John R. Jones. The division’s four brigades formed a double line with two brigades in each line. The front line consisted of the 450 soldiers of the Stonewall Brigade, commanded by Colonel Andrew Grigsby of the 27th Virginia, and the 400 men of Jones’ old brigade, led by Captain John Penn of the 42nd Virginia. The second line consisted of Brig. Gen. William Taliaferro’s 500-man brigade. Taliaferro was not present, as he was recuperating from wounds received at Brawner’s Farm, so Colonel Edward Warren of the 10th Virginia had temporarily taken his place as brigade commander. Brigadier General William S. Starke led the 650 muskets of the other brigade in the second line.

To the right of Jones’ division was Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s division, commanded on the day of the battle by Brig. Gen. Alexander Lawton in place of Ewell, who was recuperating from a debilitating wound received at Second Manassas. Ewell’s other three brigades faced off against the divisions of Meade and Ricketts.

Brigadier General Abram Duryee’s brigade from Ricketts’ division made first contact with the Confederates. Duryee’s men had tried to advance through Miller’s cornfield, but were driven back by the Georgians of Lawton’s brigade. These six Georgia regiments, which were commanded by Colonel Marcellus Douglass of the 13th Georgia, held a field of clover south of the cornfield. When Douglass was killed early in the battle, command devolved to Maj. John H. Lowe of the 31st Georgia. The Georgians repulsed Duryee’s New York and Pennsylvania troops.

As for Gibbon’s brigade, the 2nd and 6th Wisconsin regiments led the brigade with the 19th Indiana and 7th Wisconsin regiments in close support, with Battery B split to support both wings of the brigade. Lieutenant James Stewart led a two-gun section that crossed to the west side of Hagerstown Pike to support the right wing, while battery commander Captain Joseph B. Campbell stationed his men on the east side of the pike to support the left wing.

As the Black Hat Brigade slowly made its way through the Poffenberger farm towards the Miller farm south of it, shells began bursting in the trees over their heads. The exploding shells rained down shell fragments, branches, and leaves on the soldiers. The first few shells burst in rapid succession. “Then a percussion shell struck in the very center of the moving mass of men,” Dawes said. The shell struck a threshing machine before exploding, killing two men and wounding 11. The soldiers of the regiment pressed forward without halting and took temporary shelter behind Joseph Poffenberger’s barn. Hooker arrived and made the barn his headquarters. Confederate skirmishers advanced into the cornfield using head-high corn for cover; Dawes sent his skirmishers to drive out their Rebel counterparts.

Stewart unlimbered his two guns in front of some haystacks near the barn 30 yards west of Hagerstown Pike, while Campbell’s guns deployed on a low rise east of the pike. Stewart placed his limbers behind the stacks to protect the horses from enemy infantry posted 400 yards away. The lieutenant ordered the guns to be loaded with spherical case shot, an anti-personnel shell consisting of large iron balls designed for air bursts. After several of these rounds burst over them, the nearest group of Rebels dashed across a hollow and ran into the cornfield. “Under cover of the fences and corn, [the enemy] crept close to our guns, picking off our cannoneers so rapidly that in less than 10 minutes there were 14 men killed and wounded in the section,” recalled Stewart.

Campbell directed his artillery crews to fire canister, cans of explosive filled with small iron balls, into the cornfield. “In less than 20 minutes, Captain Campbell was severely wounded in the shoulder, his horse shot in several places, and the command of the battery devolved upon me,” Stewart said. The battery was taking heavy casualties at that point.

A picket fence around Miller’s garden delayed the arrival of the left wing of the 6th Wisconsin. Dawes ordered his men to knock down the fence, but it proved sturdier than expected. The Wisconsin men decided instead to file through a gate in the fence. Once through the gate, they quickly formed up alongside the rest of the regiment.

Gibbon directed the 19th Indiana and 7th Wisconsin to deploy on the west side of the turnpike. Callis’ troops formed up adjacent to the turnpike, and Bachman deployed his 19th Indiana regiment to its right. These troops began a steady advance towards the enemy-held West Woods. Meanwhile, Colonel Walter Phelps’ 1st Brigade of Doubleday’s division deployed in line of battle east of the pike to support the 2nd and 6th Wisconsin Regiments.

On the Confederate side, Jones had left the field early in the battle, claiming that a Union shell that exploded directly overhead had severely stunned him. Starke took command of the division, and Colonel Jesse Williams took charge of Starke’s brigade.

The front line of Jones’ division initially held its ground against the Yankees west of Hagerstown Pike. On the east side of the pike, the 2nd and 6th Wisconsin Regiments paused at a rail fence before advancing into the cornfield. Shortly afterwards, they pushed into the tall corn, halting when they reached a low ridge in the middle. Bragg took control of the three right companies of the 6th Wisconsin in the turnpike and gave Dawes command of the companies on the left. As they were sorting this out, the 19th Indiana and 7th Wisconsin Regiments became heavily engaged with Grigsby and Penn’s brigades, which had emerged from the protection of the West Woods.

At that time, Brig. Gen. Marsena R. Patrick’s brigade from Doubleday’s division came up behind the 19th Indiana and 7th Wisconsin to lend weight to their attack against the West Woods. With Patrick’s troops in support, Gibbon’s two regiments on the right pushed forward, allowing the men of the 19th Indiana to fight their way into the north end of the West Woods.

Private E. E. Stickley of the 5th Virginia Regiment of the Stonewall Brigade recalled the impressive advance of the Federals. “The Federals in apparent double battle line were moving toward us at charge bayonets, common time, and the sunbeams falling on their well-polished guns and bayonets gave glamour and a show at once fearful and entrancing,” he wrote.

When the Confederates moved one of their artillery pieces onto the pike, Bragg ordered one of his companies to move forward and shoot the horses attached to the cannon. At the same time, he ordered Companies G and K to seize the cannon once the horses were slain. As soon as the two companies advanced, though, they spotted large numbers of Rebels along the fence on the east side of the road. The Rebels had another line of battle parallel to the pike near the West Woods.

The Confederates opened a heavy fire on the three companies of the 6th Wisconsin in the turnpike. Bragg ordered his men to take up a prone position behind the turnpike fence and return fire. The opposing lines were only 30 yards apart in some places.

The rest of the 6th Wisconsin did not receive fire until it reached the top of the rise of ground in the middle of the cornfield. The Confederates in the clover south of the cornfield poured a heavy fire into the companies on the 6th Wisconsin’s left. “The bullets began to clip through the corn, and spin through the soft furrows, thick, almost, as hail,” wrote Dawes, who commanded the left wing of the 6th Wisconsin’s battle line. “Shells burst around us, the fragments tearing up the ground, and canister whistled through the corn above us.”

To support the companies of the 6th Wisconsin already in the cornfield, Lt. Col. Thomas S. Allen’s 2nd Wisconsin deployed on their left. About this time, Dawes received an urgent message from Bragg instructing him to come to Bragg’s position on Hagerstown Pike. When Dawes arrived, he found Bragg suffering from a very painful wound in his left arm. Bragg turned over command of the 6th Wisconsin and was escorted to the rear.

Dawes decided to remain in the turnpike, where he could command the three companies of his regiment who were defending their position behind the post and rail fence on the east side of the turnpike. From that vantage point, Dawes also could keep an eye on the progress of the companies on his left in the cornfield.

Gibbon’s troops in the cornfield advanced at an oblique angle with their front facing southwest towards the West Woods. As the soldiers advanced, the men could see the whitewashed Dunker Church ahead of them nestled in a nook in the West Woods just to the right. Unfortunately, they did not see a line of Georgians lying in wait for them.

“Simultaneously, the hostile battle lines opened a tremendous fire on each other,” recalled Dawes. “Men were knocked out of the ranks by dozens, but we jumped over the fence and pushed on, loading, firing, and shouting as we advanced.” The three companies of the 6th Wisconsin in the turnpike rushed forward to help their fellow soldiers.

While the Wisconsin men on the left were advancing obliquely through the cornfield, the 19th Indiana and 7th Wisconsin west of the turnpike held their ground at the north end of the West Woods against a concerted attempt by the Rebels to capture Stewart’s guns. The lieutenant had ordered his gunners to fire canister at the enemy troops approaching the guns. The Hoosiers fired into the flank of the attacking force, dispersing the Confederates trying to seize the guns. Bachman then ordered his troops to charge. “Hat in hand and sword drawn, [Bachman] gave the order ‘double-quick,’ and bravely led on, the men following, cheering as they advanced,” wrote Captain William W. Dudley of the 19th Indiana.

The Hoosiers surged forward shouting, “Huzzah!” They “followed the retreating rebels to the brow of a hill, over which they had a strong reserve of infantry and three pieces of artillery,” Dudley said. As they crested the hill, Bachman was mortally wounded, and Dudley took command of the 19th Indiana.

The rightward half of Gibbon’s brigade had the Confederates of Jones’ brigade on the run. When Penn tried to rally his retreating Virginians, he received a wound that would cost him his leg. Captain Archer Page of the 21st Virginia took command of Jones’ brigade. By then, the first line of Jones’ division had been shattered, and Gibbon’s right regiments had taken possession of the north end of the West Woods.

Jackson had assembled 13 guns at the eastern edge of the West Woods that were shelling the Yankees as they sought to drive the Confederates once and for all from the woods. Captain John B. Brockenbrough’s 2nd Baltimore Artillery had all six of its rifled artillery pieces in action. In addition to three 3-inch ordnance rifles, the battery had a 12-pound Blakely rifle, a 12-pound Parrott, and a 10-pound Parrot assailing the Federals.

Receiving heavy fire from the Confederates, the 19th Indiana fell back in disorder to the pike, where their officers rallied them. In the see-saw fighting, their regimental colors fell three times but each time were raised again. Grigsby ordered his surviving Virginians to change front to face east; they poured a devastating fire into the right flank of the 19th Indiana, driving the Hoosiers back to their original position alongside the 7th Wisconsin.

Although the 2nd and 6th Wisconsin eventually drove off the Confederates defending the clover field adjacent to the cornfield, “the line stopped by common impulse, fell back to the edge of the corn and lay down on the ground behind the low rail fence,” wrote Dawes.

One of the last men to run back into the corn was Private Bob Tomlinson of the 6th Wisconsin. When begged by his comrades to retreat with the rest, he told them he had a few more cartridges left. Standing alone, he fired his last round. When finished, he walked calmly back into the cornfield.

Having suffered heavy losses against Gibbon’s regiments on the right wing, Grigsby requested that Starke reinforce the beleaguered Stonewall Brigade. Eleven hundred and fifty fresh Rebel troops surged into action west of the pike. Meanwhile, Grigsby’s remaining troops took cover behind limestone outcroppings and continued firing on Gibbon’s troops west of the turnpike.

“We commenced removing the fence in front of us when the enemy opened a destructive fire from the woods in our front,” Callis wrote. “Our men returned the fire, and charged over the fence.” The men of the 7th Wisconsin maintained a steady fire until Starke’s troops emerged from the West Woods, crossed Hagerstown Pike, and fought their way into the cornfield. Most of Gibbon’s brigade, except perhaps for parts of the 19th Indiana on the extreme right, became engaged against Starke’s force.

Starke, who was on horseback, grabbed his brigade’s flag and led them forward in an all-out charge against Gibbon’s brigade. Just a few minutes into the charge, he was struck by three bullets that knocked him from his horse. He was dead within an hour. His troops initially drove the Yankees back, and the two sides exchanged fire at across Hagerstown Turnpike. Some of the Confederates managed to scale the fence and take up a position in the road but were soon forced to retreat. The Yankees prevailed and dislodged the Rebels, firing at the Confederates as they retreated to the West Woods. Starke’s brigade lost nearly 300 men, and Taliaferro’s brigade lost 170 men.

The soldiers of Gibbon’s brigade who had engaged Starke’s Rebels found that their rifled muskets had become so fouled that it was difficult for them to drive home a bullet with their ramrods. As a result, their fire slowed considerably.

The 14th Brooklyn Regiment and the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters of Phelps’ brigade arrived to reinforce the exhausted men of the 6th Wisconsin, taking up positions behind them, though some men of the 14th Brooklyn and the sharpshooters stepped forward to fight alongside the 6th Wisconsin. These commands became intermingled, with the black hats of the Badgers interspersed here and there with the red kepis and trousers of the Empire Staters and the dark green uniforms of the Sharpshooters.

“Men and officers of New York and Wisconsin are fused into a common mass in the frantic struggle to shoot fast,” wrote Dawes. “Everyone tears cartridges, loads, passes guns, or shoots. Men are falling in their places or are running back into the corn.”

This line was soon ravaged by Rebel artillery and musketry. Men fell to the ground dead or grievously wounded. Because of this, the survivors took it upon themselves to withdraw to a depression in the ground, where their officers rallied them.

The soldiers from Wisconsin and New York advanced into the clover field once again. They were approaching the Dunker Church when Confederate reinforcements swept out of the West Woods and overran their right flank. Dawes said that the volley cut through their line like a scythe. The Yankees retreated in disorder through the cornfield with the Confederates close behind.

These fresh troops belonged to Brig. Gen. John B. Hood’s division of Longstreet’s I Corps. Lee had earlier sent them to Jackson to reinforce his left wing. Before the battle began, Hood asked Jackson for permission to allow his men to cook breakfast. They had just received a meat ration and had hardly had anything to eat in a week of hard marching. Jackson had granted Hood’s request on the condition that if they were needed, they would respond immediately. Interrupted while they were still cooking their food, these Rebels were angry and planned to vent their wrath on the Yankees.

The Confederates of Hood’s division surged north screaming the high-pitched, blood-curdling Rebel Yell. Hood’s old brigade, led by Colonel William Wofford of Georgia, had earned a reputation as shock troops for piercing a heavily fortified Union line at Gaines’ Mill two months earlier, and their performance that morning further solidified their reputation. Hood’s men cleared the cornfield of Yankees.

Lieutenant Colonel B. F. Carter, commanding the 4th Texas Infantry, stumbled upon the Federals in strong force in a ravine to the left of the turnpike. This force was the three companies of the 6th Wisconsin who had withdrawn from their vulnerable position on Hagerstown Pike and had taken shelter in the ravine. The Yankees “poured a destructive fire upon us,” wrote Carter. The lieutenant ordered his regiment to wheel to the left and take shelter behind the rail fence.

The three Wisconsin companies then withdrew to join the rest of their regiment north of the cornfield. The Confederate counterattack “had driven the Yankees from the cornfield back upon their reserves,” Hood stated in his battle report. Gibbon’s account echoed that of Hood. “Under repeated assaults, my men now came rapidly to the rear,” he wrote.

Across Hagerstown Pike from the 6th Wisconsin, Dawes could see one of the cannons of Stewart’s section of Battery B in action near some straw stacks. The close proximity of Hood’s line posed a dire threat to Stewart’s two guns. Seeing the danger, Gibbon ordered Dawes to save them. The major grabbed his regiment’s colors and led the survivors across the pike to secure the guns.

The crew manning one cannon in the pike had forgotten to adjust its elevating screw. Because of this oversight, the gun fired over the heads of the Confederates. Gibbon yelled to the gunner to run up the screw, but he could not make himself heard in the tumult from the battle. He jumped off his horse and ran over to the gun. “[I] rapidly ran up the elevating screw until the muzzle pointed almost into the ground in front and then nodded to the gunner to pull the lanyard,” he wrote. The gun, charged with canister, bounced the shot and “carried away most of the fence in front of it and produced great destruction in the enemy’s ranks.”

The crew of the gun maintained their fire. They rammed home double-shotted canister that felled many Rebels. Despite the severe fire, the veteran Texans continued to press their attack. Stewart had great difficulty withdrawing his guns because the men and horses were falling too fast. Under the heavy pressure from the Rebels and his mounting losses, Stewart was unable initially to limber his guns in order to save them.

Seeing the crisis unfold, Gibbon called on Doubleday for assistance. Doubleday responded by sending half of a New York regiment but, as it turned out, they were not needed. The heavy fire from Stewart’s guns had succeeded in keeping the Rebels at bay. “Nothing could withstand the fire of those double-shotted Napoleons, which finally beat off the enemy,” wrote Gibbon. As soon as the Rebel attack played itself out, Stewart was able to limber his two cannon and withdraw north through the double gates of Miller’s garden.

The retreat through the North Woods to the Poffenberger barn was not easy. “Bullets, shot, and shell, fired by the enemy in the cornfield were still flying thickly around us, striking the trees in the woods, and cutting off the limbs,” wrote Dawes. After retreating to the barn, Dawes positioned his men under the best shelter he could find and then went about tallying their losses.

The 7th Wisconsin and 19th Indiana were still on the edge of the West Woods that extended to the southwest corner of the Miller field, facing east. The Confederates had positioned an artillery battery 300 yards to their right. A heavy force of infantry was assigned to support the battery. “They began throwing…canister into our ranks with terrible effect,” wrote Callis. The two regiments retreated from the West Woods and rejoined the rest of the brigade in the rear.

“A heavy force of the enemy had taken possession…and from the sun’s rays falling on their bayonets projecting above the corn I could see that the field was filled with the enemy,” wrote Hooker. The I Corps commander ordered six batteries to be unlimbered and placed in a ravine between the North Woods and the cornfield. The Union artillery wrought havoc on the Confederate positions. “Every stalk of corn…was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks,” Hooker said of the carnage in Miller’s cornfield.

Of the approximately 800 men of the Black Hat Brigade who went into action that day, 348 became casualties. When it was all over, the cost of the fighting on September 17 was staggering. The Federals suffered 2,108 dead and 9,540 wounded, whereas the Confederates suffered 1,546 killed and 7,752 wounded. One in every four Union soldiers and one in every three Confederates became casualties at Antietam. When the American Civil War ended in 1865, the Battle of Antietam would stand out as the single bloodiest day of the war.