By Dick Camp

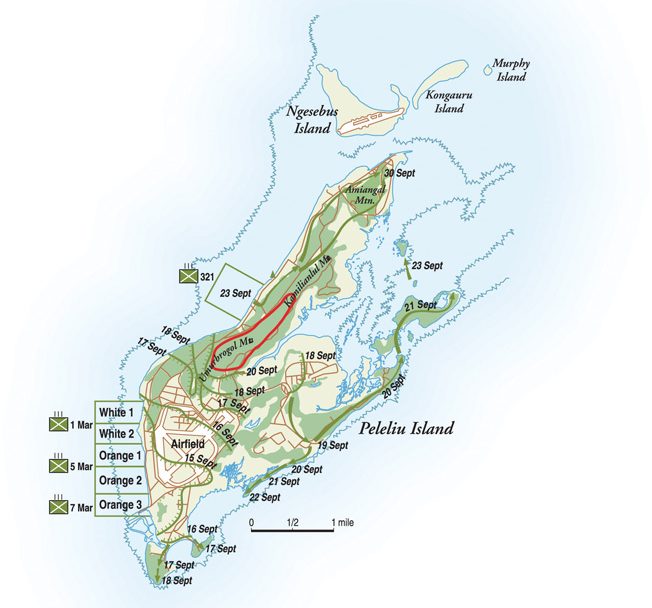

By the summer of 1944, the United States was advancing on Japan’s Home Islands in a two-pronged attack through the Central and Southwest Pacific theaters. Japan’s first line of defense in the Marshall and Mariana Islands had been shattered. General Douglas MacArthur’s southwestern forces had reached the western extremity of New Guinea and were preparing for a move onto the Philippine island of Mindanao, to honor his “I shall return” promise. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, directed the seizure of the southern Palaus in the western Carolinas to “remove a definite threat from MacArthur’s right flank, and to secure a base to support his operation into the southern Philippines.” On July 7, 1944, he designated it Operation Stalemate II and assigned Phase I, the capture of Peleliu, a target date of September 15.

Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, Jr., commander of the Third Fleet, was charged with the initial preparation of the Palau operation by “seeking out and destroying hostile air and naval forces that threaten Stalemate II.” He launched his fast carrier task force in far-flung sweeps that ranged from the Bonin Islands south to the Philippines and was surprised at the weakness of the Japanese opposition. “Enemy’s non-aggressive attitude unbelievable and fantastic,” he wrote. “We found the central Philippines a hollow shell.”

After carefully considering the sweep’s success, Halsey sent a message to Nimitz recommending the cancellation of the Peleliu operation because there was no serious threat to MacArthur’s flank. “I’m going to stick my neck out,” he remarked, adding later that “such a recommendation would upset many apple carts, possibly all the way to Mr. Roosevelt and Mr. Churchill.” Nimitz received the message but did not concur and ordered Operation Stalemate II to proceed as planned.

Chosen to assault the small island (only six square miles) was the 1st Marine Division––a seasoned outfit that had already taken part in the seven-month-long battle for Guadalcanal (August 1942-February1943). Guadalcanal (including Florida and Tulagi Islands) was the first American land offensive of the war, and it cost the 1st and 2nd Marine Divisions 991 dead, 2,894 wounded, and 51 missing and presumed dead. It also earned the 1st Marine Division a Presidential Unit Citation and the respect and admiration of a nation.

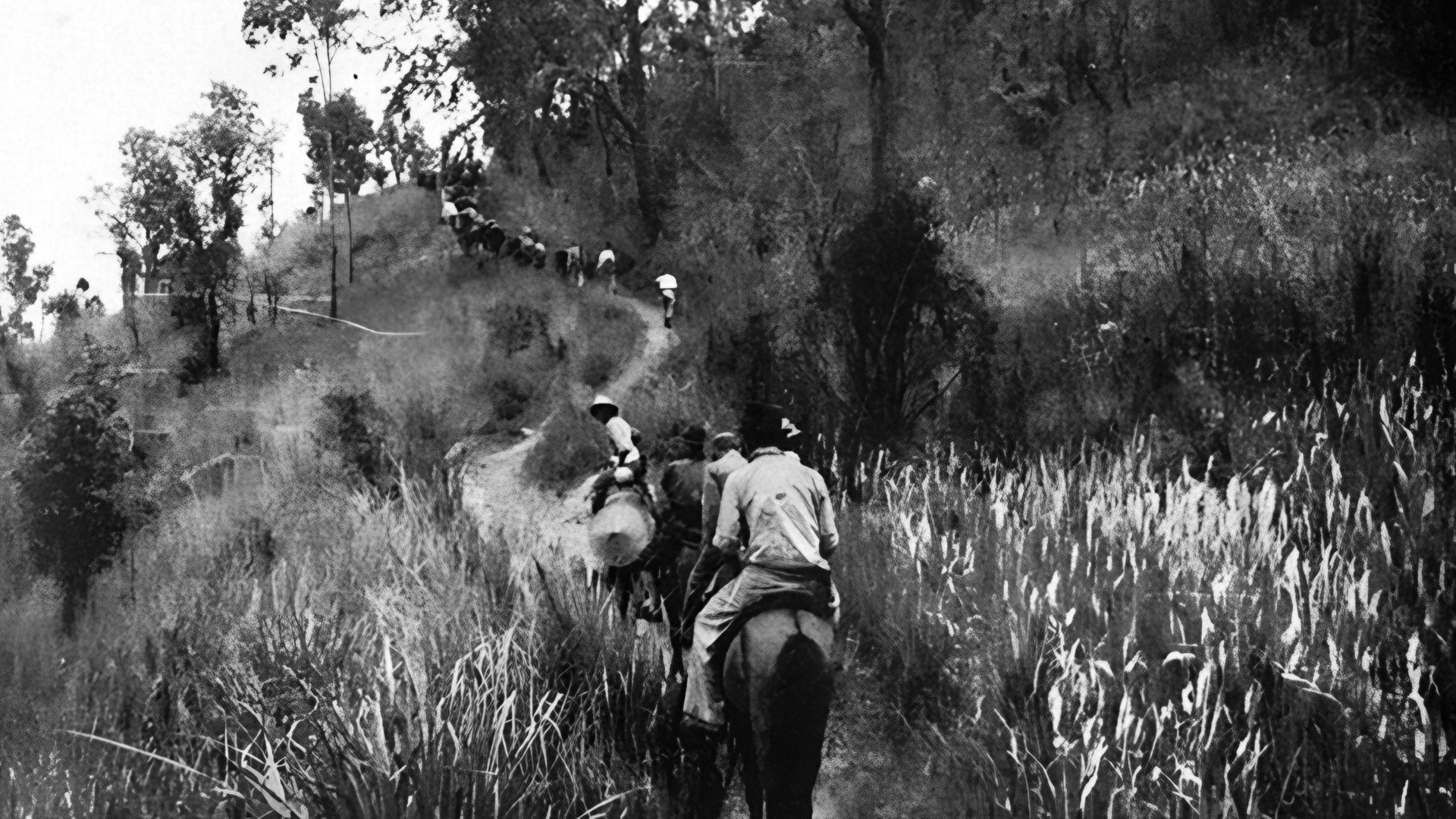

After Guadalcanal came the fight for Cape Gloucester on New Britain (December 1943). Okinawa lay ahead. As would every battle for every Pacific island, Guadalcanal and Cape Gloucester represented jungle fighting at its worst: energy-sapping heat and humidity, close-quarters combat, night battles, fanatical banzai charges, monsoonal downpours, disease, festering wounds, and an enemy that preferred to die rather than surrender.

Following Cape Gloucester, the 1st Marine Division got a well-deserved break at Pavuvu in the Russell Islands, just north of Guadalcanal.

But no successful military unit gets to rest on its laurels for very long. Soon Maj. Gen. William J. Rupertus received orders alerting his division that it would be the leading assault force against the Japanese garrison at Peleliu.

By the summer of 1944, the Japanese had some 30,000 troops stationed in the Palaus, with about 11,000 of those on Peleliu––primarily from the 14th Infantry Division, augmented by Korean and Okinawan laborers. These workers had honeycombed the island with miles of underground bunkers, living quarters, and fighting positions. Thousands of mines had been buried at the beaches the Japanese commander thought the Americans likely would use.

On September 4, the Marines left their station on Pavuvu for the 2,100-mile trip to Peleliu. Standing offshore, the sizable Navy armada (five battleships, five heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, three aircraft carriers, and five light carriers) began pounding the island with a pre-invasion bombardment on September 12.

The three-day-long naval barrage and aerial attacks that shrouded the island in dirty gray smoke and gave the Marines waiting in their transports the hope that maybe, this time, all those shells would actually mean an easy landing. Their hopes would prove unfounded.

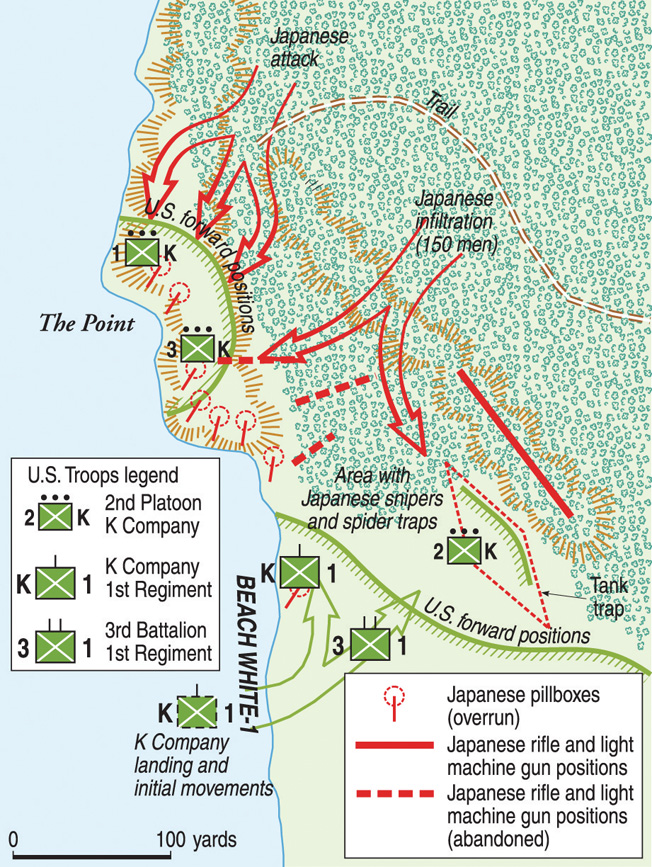

Three days later, on the morning of September 15, 1944, the 1st Marine Division headed for Peleliu against the fanatical Japanese, who, burrowed deeply in their subterranean fortress, were largely immune to the thousands of bombs and shells. The landing beaches were described as a hell on earth by the veterans who had to assault through murderous mortar, artillery, and automatic weapons fire. One spit of land on the extreme left flank of White Beach 1 was particularly vicious. It contained two anti-boat guns, several machine-gun positions, and entrenchments that were pouring fire into the flank of the assault force. K Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment was given the mission of knocking them out.

“They’ve Come at Last”

Hundreds of explosions rocked the earth in a cacophony of sound that threatened to overwhelm the senses. Huge fountains of blast-torn earth and coral reached skyward. A towering wall of smoke, stinking of cordite, obscured the island’s interior. One tiny spit of land jutting out from the beach, however, remained free from bombardment, a haven of relative tranquility in a sea of violence.

The six-man crew of the Japanese 75mm mountain gun (Yonichi Shiki Sampo) peered fixedly through the narrow embrasure of their concrete reinforced bunker. They were mesmerized by the sight of a line of strange vehicles that rose out of the sea and clambered over the outer fringe of the reef. One knowing veteran muttered, “They’ve come at last.”

The sharp bark of a noncommissioned officer interrupted his thought and sent him scampering to his action station. A gunner snapped open the breach, while another slammed an armor-piercing shell into the opening, just as one of the strange vehicles came into range. “Fire!” the NCO shouted.

White Beach

White Beach, a 656-yard concave strip of sand on the 1st Marine Division’s left flank, was dominated by a pitted spit of land that jutted out from the island and was well fortified. “The point, rising thirty feet above the water’s edge,” Captain George P. Hunt described, “was of solid, jagged coral, a rocky mass of sharp pinnacles, deep crevasses, and tremendous boulders. Pillboxes, reinforced with steel and concrete, had been dug or blasted in the base of the perpendicular drop to the beach. Others, with coral and concrete piled six feet on top were constructed above, and spider holes were blasted around them for protecting infantry.”

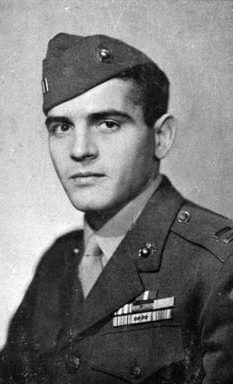

Hunt’s K Company was assigned to take the heavily defended position. “Colonel [Lewis B. “Chesty”] Puller, [CO, 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division] gave me the toughest job of taking the left flank because he had developed a respect for my company,” Hunt said. It was an awesome responsibility. “Should we fail to capture and hold the Point, the entire regimental beach would be exposed to heavy fire from the flank,” he articulated.

His reinforced rifle company numbered 235 officers and men consisting of three rifle platoons, a mortar section (three 60mm mortars), a three-section machine-gun platoon (six .30-caliber Browning machine guns), and a small headquarters platoon. Many of his men were combat veterans of Guadalcanal and Cape Gloucester. They were supremely confident of themselves and their company. “We were proud of our responsibility,” Hunt expressed, “and every man in the company was determined to fill it.”

Aerial photographs of the objective “showed anti-boat obstacles on the coral reef in front of the beach, entrenchments on the beach itself, and two pillboxes,” Hunt recalled. After carefully studying them, he decided that his company would “perform a gate-like maneuver by pivoting 90 degrees to the north with our left flank anchored on the beach.”

Hunt assigned the 3rd Platoon to clear the point, while the 2nd Platoon assaulted the right half of the company objective. The 1st Platoon was to follow in trace of the 3rd Platoon. He attached one machine-gun section to each of the two assault platoons and kept the third section in general support, along with the 60mm mortars. The company practiced the maneuver over and over until “every man in the company knew what to do in relation to the man next to him.”

D-day

Riding in a tracked, open-top amphibious vehicle known as an amtrac, Hunt braced himself as “the nose of the amtrac shot upward, hung in mid-air; the tracks took hold, and we leveled off and jerked to a halt.” He shouted, “Get out and off the beach,” to his men and rolled over the side of the vehicle. “The impact of the eight-foot jump jarred my legs and momentarily upset my balance. Regaining it, I raced off the beach.”

He ran for about 75 yards with bullets thwacking the sand around him and explosions erupting in a seemingly endless barrage before going to ground in a shell hole. “My lips and tongue [were] as dry as sandpaper,” he recalled. “Black vapor and the pungent odor of gunpowder which was seeping from the earth helped to clog my throat. Sweat was running off the end of my nose.”

As the command group took cover around him, his radio operator tried to raise the platoons—but without success. Suddenly mortar fire erupted, bracketing them. Small-arms fire snapped overhead. The plaintive cry of “Corpsmen!” rose above the din—it was pandemonium on the beach.

Hunt struggled to get a clear picture of the situation. “I had to know what was going on … the uncertainty was agonizing.” He sent runners out to gain information but they failed to return. A wounded man stumbled into the makeshift command post exclaiming, “There are K Company guys dead and wounded lyin’ all around.” The situation was grim. Something had to be done—and quickly. Hunt reached a decision.

He rolled out of the hole, yelling for his radio operator to follow, and headed for the Point. As he ran along the shell-blasted sand, he was shocked to see the full impact of the Japanese fire. “I saw a ghastly mixture of bandages, bloody and mutilated skin; Marines gritting their teeth resigned to their wounds; men groaning and writhing in their agonies; men outstretched or twisted or grotesquely transfixed in the attitudes of death; men with their entrails exposed or whole chunks of body ripped out of them.”

Hunt discovered that the 3rd Platoon had landed 100 yards too far to the right and was pinned down about 50 yards from the point. During its hard-fought assault, the platoon had knocked out one 40mm gun, two heavy machine guns, and numerous light machine guns, but the gains had been at the cost of the platoon’s leadership. The platoon commander was badly wounded and out of the fight.

The platoon sergeant, John Koval, “unhesitatingly assumed command and, despite a wound sustained from leading an assault against enemy pillboxes and infantrymen entrenched in spider holes along the beach, tenaciously continued pressing the attack toward a Japanese antiboat gun emplacement, which was inflicting heavy damage on our landing craft,” his posthumous Navy Cross citation read. “Although wounded a second time and in a dying condition, he courageously directed the final assault and was responsible in large measure for the destruction of the enemy gun.”

The 2nd Platoon was badly shot up, its platoon commander dead on the beach, and the platoon sergeant wounded. The leaderless men fought their way through 75 yards of rifle and machine-gun fire to a 10-foot-deep tank trap where they were pinned down by extremely heavy fire from an unseen enemy dug into a coral ridge.

The boulder-strewn, tree-blasted high ground rose 30 to 40 feet high and was studded with heavily camouflaged Japanese machine-gun positions. Pfc. Joe Dariano recalled, “Our guys were dropping all around me. We were totally unorganized—without officers or squad leaders, and completely cut off from the rest of the company. Out of the 45 guys in my platoon, 19 were killed and 21 wounded.”

Clearing a Coral Bunker

Minutes after crawling out of the tank trap, Dariano was badly wounded in the head and shoulder. The remnants of the platoon were trapped, cut off from help, and unable to maintain contact with the 3rd Platoon. The gap was quickly filled by the Japanese.

Private First Class Fred Fox came face to face with a Japanese soldier who ran by him before he could get a shot off and disappeared into a well-camouflaged coral bunker. “I couldn’t see an embrasure but there was a stairway cut into the coral going down into the ground. I threw a white phosphorus and two regular hand grenades down there, but nobody came out. So, I took a couple of steps down to where I could see clearly. A Japanese officer, with cloth cap and black-rimmed glasses lay at the bottom of the steps. His left arm was burnt black but he was leaning on his elbow with a Nambu pistol in his hand aimed at me. I pressed the trigger on my Tommy gun and fired four or five rounds into him. I went on down the steps and into the middle of a 12-by-15-foot room. There was another officer with a sword stuck in his belly, sticking up in the air. There were several other Jap bodies in the back corner.” Fox beat a hasty retreat after relieving the body on the stairs of its pistol.

Captain Hunt finally made contact with 1st Platoon’s Lieutenant William L. Willis and ordered him to push through the stalled 3rd Platoon and take the point. The fortifications were constructed of steel-reinforced concrete surmounted by five feet of coral rock and manned by six to 12 enemy soldiers. Willis led the attack on the last emplacement.

“Only Thirty Men in Fighting Condition on Top of the Point”

Willis’s Navy Cross citation described how he led his men forward in a daring and skillful assault: “The fierce hand-to-hand conflict reached a high pitch of intensity when he and his men penetrated the Japanese ring of infantrymen and were assaulting the pillboxes themselves.”

“A squad covered the rear exit of the pillbox,” he explained. “Anderson, one of my corporals, sneaked part way down the rocks about twenty yards in front of the embrasure, while I crawled to a cut in the cliff where I could heave a grenade without being shot.”

Lieutenant Willis threw a white phosphorous grenade that obscured the vision of the Japanese defenders while Anderson fired a rifle grenade at the embrasure. “The grenade launched perfectly and smacked the gun on the barrel,” the officer recalled. “It ignited something flammable, and after a big explosion the pillbox burst into flame. Black smoke poured out of the embrasure and the exit. I heard the Japs screaming and their ammunition spitting and snapping as the heat exploded it. Three Japs, with bullets popping in their belts and flames clinging to their legs, raced from the exit waving their arms and letting out yells of pain. The squad I had placed there finished them off.”

With this last pillbox destroyed, Hunt gathered the remnants of K Company and established a hasty defense. One of the survivors estimated that “out of perhaps ninety in the two platoons, we had only thirty men in fighting condition on top of the point.”

George Hunt counted 110 dead Japanese in and around the blasted hilltop but estimated that nearly two-thirds of his company were casualties, including “most of my machine-gun platoon that had been mowed down on the beach.”

The small band of battered men piled up coral rocks for protection. All afternoon the Japanese staged scattered infantry and mortar attacks on the skimpy positions. The Marines held, but more and more men were lost. All the company machine guns had been knocked out, and Hunt had resorted to using a captured Japanese heavy machine gun on the lines. The irrepressible Fred Fox had “liberated” it from its dead crew.

“I found the air-cooled Hotckiss in a small clearing; two dead Jap bodies lay alongside it,” Fox remembered. “We carried the gun up to the point, and gave to [Corporal Bob Anderson] from the machine-gun platoon. I had no desire to keep carrying the damn thing anyway.”

Late in the afternoon, an LVT (amphibious vehicle) was able to make its way to the point with badly needed supplies of ammunition, barbed wire, C rations—and water. “The water was brought up in a 55-gallon drum,” Fox recalled, “but the drum had not been cleaned properly and the water tasted awful, sickening. It was oil and water and no way could you drink it. So, when you got the chance you went out, found some dead Jap bodies. and took their canteens.”

After replenishing his supply of ammunition, Fox tried to scrape a foxhole in the coral but it was impossible. Instead, he just piled it up for protection and then carefully laid out hand grenades and rifle clips so he could find them in the dark. There was nothing else to do except wait. “I guess we all knew that something unpleasant was going to happen … this was the Japanese’s time, their time to fight.”

Hunt made a last tour of the lines. “As blackness crept up and completely enveloped us, we were subdued to an eerie silence. Even the clicking sounds of a rock, probably brushed off by the sweep of a man’s elbow, seemed a harsh disturbance. Though there was no moon, the sky … was just light enough to reveal the weird and grotesque silhouettes of knotted trees and stumps.” Jagged, pinnacled rocks melded with the gnarled tree remains, providing cover for Japanese infiltrators. Their odd shapes played tricks on the Marines’ imaginations, transforming them into Japanese attackers in the darkness.

“The Jap loves the night and he loves to sneak,” Hunt philosophized. “He is an animal who prowls noiselessly with padded, two-toed shoes on his feet. When he attacks … out of the night … with bayonet and knife, he is dangerous and clever.”

Japanese Raiding Units

The Japanese had always used infiltration as a means to counteract massed American firepower. Peleliu, however, marked the first time that they used infiltration and raiding units as part of their defensive strategy. A captured Japanese document outlined five types of night-raiding units: (1) pillbox defense units; (2) close combat infiltration units; (3) prearranged fire units (called sudden fire units by the Japanese); (4) combined fire power and close combat units; (5) incendiary assault units.

The members of the units were extensively trained in night infiltration and raiding techniques. The training stressed thorough preparation, camouflage and concealment and small-unit close combat. They were lightly armed—light machine guns, grenade dischargers (knee mortar), and small arms—and whenever possible wore U.S. uniforms and equipment. Their attacks were launched from prepared positions placed about 220 to 275 yards behind the beach positions. The unit remained in hiding until after the beach fighting was over and then attempted to attack key emplacements, such as command posts, artillery positions, etc. In a sense, the raiding units replaced the fanatical banzai attacks that had proved so costly.

Terror in the Night

Private First Class Fox shared a foxhole with a buddy. “Some time between 11 and 12,” he said, “we heard movement out in front.” Pfc. Swede Hanson was close by. “You could hear movement going about, and your ears got bigger and bigger because you’re wondering: Is it a Marine or is it a Jap? And you didn’t want to take a chance … so I started throwing hand grenades out there in front. And then I waited. Then, brrrr, that Nambu machine gun. So I threw a couple more grenades out there and I heard it again. It took a little longer to get that one.”

Captain Hunt requested illumination. “Flares swished up from the rear. I prayed they wouldn’t break over our own position and light us up … but they burst well in front of us, flooding the area with light.” Someone shouted “Here they come!” and the fight was on.

“A machine gun fired a burst,” Hunt exclaimed. “Another one opened up with a vibrating roar, BARs [Browning Automatic Rifles] and rifles … hand grenades were bursting in rapid succession. The explosions were muffled in the woods, where there were gullies and ridges. Then much louder bursts—approaching our lines—closer—and I heard the cry ‘Corpsman!’ Jap mortars, big stuff, were pounding in the middle of us. Shrapnel was clinking across the rocks.”

Corporal Bob Anderson manned the captured Japanese machine gun. “Whenever someone heard the Japs jabbering, they would call for a star shell [illumination] and when it would go off, we could see Japs running out to our front. Then I would open up with the machine gun at the running Japs. I don’t know if I hit any or not, but I used up a lot of ammunition.”

Hunt recalled, “White muzzle flashes spit into the black. The noise increased as the Japs answered and their bullets splattered on the rocks and ricocheted in every direction. Their mortar shells thundered into the coral, raising the stink of gunpowder.”

Suddenly the Japanese attack stopped. At first light, the ground in front of the lines was strewn with enemy dead. One Marine veteran said, “I never saw so many dead Japs in one place in all my days of combat.”

D+1

Early in the morning of September 16, Hunt was resupplied and reinforced. “Tractors [amphibious vehicles] rolled up to us all day along the reef. They brought my mortar section … with clover leaf after clover leaf of shells. They brought up an artillery observation team and a radio to communicate with the gun batteries—and the remaining 10 men from my 2nd Platoon.”

With the resupply and reinforcement, Hunt allowed that “it would be our turn to throw the heavy stuff: mortars and artillery. We had seven machine guns on the line and 30 more men. Radios were working, and there were two telephone lines to battalion. For the first time since we landed we felt secure.”

Hunt felt strong enough to send a patrol out in front of his lines. After a short, vicious firefight that cost the lives of three men, the patrol leader reported back, “There’s a mess of ‘em in the caves—take a hell of a lot of men to rout ‘em out.” Hunt reported to his battalion commander that there were “still plenty of Japs in front of us—seem to be gathering for something—maybe a night attack.”

“Give ’em Hell!”

Fred Fox was all alone in a position close to the water. “About midnight the Japs really started the action,” he recalled. “They began with mortars and then followed up with everything else, almost a banzai charge! It was rifles, machine guns, and hand grenades—everything that was available.”

Fox heard noise in the water and started back to notify Captain Hunt when “I heard a step behind me … I turned around as fast as I could. In turning, I hit a bayonet that had started into my chest and knocked it out of the way. It cut through my jacket and left a four-inch-by-one-half-inch gash through the flesh of my left chest. I had a pistol in my hand; it was cocked and loaded but I didn’t shoot the man. I hit him in the face with it … as hard as I could. He immediately dropped the rifle, which I took and bayoneted him. I pulled it out and started yelling “Nips! Nips!”

Marines picked up the cry, “There they are!” “They’re comin’ on us!”

Hunt shouted encouragement. “I bellowed until I thought my lungs would crack. ‘Give ‘em hell!’ Kill everyone one of them!’ The Japs were assaulting us with stampeding fury, wave after wave, charging blindly into our lines—above the uproar, I heard their devilish screams, banzai, banzai!”

Marine artillery blasted the exposed Japanese and Hunt’s own 60mm mortars laid down a thick wall of shrapnel. Despite the firepower, about 30 Japanese managed to penetrate the lines. In the light of parachute flares, figures could be seen in deadly hand-to-hand struggles. Hunt watched transfixed as “two figures, dim and queerly distorted in the battle fog, fought against each other on the crest of the cliff. Their arms were swinging wildly, their heads lowered and legs intertwined. The largest figure seemed to heave forward with his entire right side. The knees of the other bent back, he turned sideways and losing his balance tumbled off the cliff.”

The Japanese attempted to go around the left flank through the water’s edge just below the cliff. Fred Fox was in serious trouble, caught between the enemy and his own men. “In a second or two there were another two or three Japs starting after me. Then there was an explosion, and I went down in the water … hit along the left side with five chunks of steel in my left leg and left arm.” Another Japanese soldier bayoneted him in the neck and across the back and left him for dead. “I lay quiet in the water,” he recounted. “At certain times I would look out of the corner of my eye … and I could see wrap leggings and split toed shoes.”

Barely conscious, Fox lay bleeding as the battle raged all around him. “The guns fired across the water over me and against the cliff,” he said. “This went on until sometime just before daylight.” His yells for help were heard. A Marine left his position, worked his way over to the badly wounded man, and carried him to safety. “He did a hell of brave thing to come out in the open to pick me up,” Fox related gratefully. Fox was evacuated to the United States where he spent eight months in various hospitals before being discharged.

When morning came, K Company still held the point––but at great cost. Marine bodies lay intermingled with Japanese in a ghastly carpet of death. The survivors stood hollow-eyed and emotionless, not quite believing they had lived through the night. Another company moved through their depleted ranks to continue the attack, leaving K Company to lick its wounds and prepare to take their place in the lines. Out of the original 235 men that landed on D-day, only 78 remained.

Captain Hunt received a few replacements—clerks, wiremen, and support troops—and reorganized. PFCs became squad leaders and the few remaining NCOs led platoons. Within days, many more of the men who landed on D-day were gone, victims of mortar, artillery, or small-arms fire, but the company continued to attack. On D+8, K Company was pulled off the lines along with what was left of the 1st Marine Regiment.

A bedraggled, worn-out Marine dragged himself up the cargo net to be taken off the island. Upon reaching the top, he was approached by an eager, clean, close-shaven, immaculately dressed young naval officer. “Got any souvenirs to trade?” the officer asked. The exhausted, sweat-soaked Marine stood silent for a moment, then reached down and patted his rear end. “I brought my ass outta there, Swabbie,” he retorted. “That’s my souvenir of Peleliu.”

Russell Davis, who served as a rifleman in the 1st Marines on Peleliu, spoke for those infantrymen who survived. “We won before. We’ll win the next one. But this time we got beat—and that’s the truth of it.”

Epilogue

The 1st Marine Division was awarded another Presidential Unit Citation for its heroic achievements at Peleliu; it would receive a third one in a few months on Okinawa. The Peleliu citation reads:

“For extraordinary heroism in action against enemy Japanese forces at Peleliu and Ngesebus from September 15 to 29, 1944. Landing over a treacherous coral reef against hostile mortar and artillery fire, the First Marine Division, Reinforced, seized a narrow, heavily mined beachhead and advanced foot by foot in the face of relentless enfilade fire through rain-forests and mangrove swamps toward the air strip, the key to the enemy defenses of the southern Palaus.

“Opposed all the way by thoroughly disciplined, veteran Japanese troops heavily entrenched in caves and in reinforced concrete pillboxes which honeycombed the high ground throughout the island, the officers and men of the Division fought with undiminished spirit and courage despite heavy losses, exhausting heat and difficult terrain, seizing and holding a highly strategic air and land base for future operations in the western Pacific. By their individual acts of heroism, their aggressiveness and their fortitude, the men of the First Marine Division, Reinforced, upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Captain George Hunt, who survived the battle, was awarded the Navy Cross for gallantry in action.

His Navy Cross citation reads as follows:

“For extraordinary heroism as Commanding Officer, Company K, Third Battalion, First Marines, First Marine Division, in action against enemy forces during the assault on enemy-held Peleliu, Palau Islands, from 15 to 17 September 1944. A bold and aggressive leader, Captain Hunt led his men in a daring assault against the enemy who were firing from concrete pillboxes on a coral point. Knowing the great danger the seizure of this point would incur, but realizing the immediate necessity for its capture, he quickly and skillfully maneuvered his company and, with two platoons, captured the point after a fierce struggle during which five hostile concrete pillboxes, numerous coral pillboxes and lighter emplacements were destroyed and over one hundred of the enemy were killed. Isolated from the rest of his battalion for a period of twenty-six hours with only thirty-four men remaining, Captain Hunt expertly organized a defensive perimeter and, successfully defending his position against three hostile counterattacks, repulsed all three of them and annihilated four hundred and twenty-two Japanese. By his outstanding leadership and cool judgment in the face of grave danger,

“Captain Hunt contributed materially to the success of our forces during this critical period, and his gallant conduct throughout was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Hunt went on to become an artist, writer, and managing editor of Life magazine. He died in 1991 at the age of 72.

Parting Shot

The veteran 1st Marine Division lost over 6,500 men on Peleliu, of whom 1,252 were killed in action. (Eight Marines would be awarded the Medal of Honor, five of them posthumously.) Having lost more than a third of its fighting strength, the division remained out of combat, resting, refitting, and training, until the invasion of Okinawa on April 1, 1945. The U.S. Army’s 81st Infantry Division, which was in reserve and replaced the Marines, lost another 1,393 men at Peleliu. Except for about 200 men taken prisoner, the defenders were entirely wiped out.

With such high casualties, the question became, “Was Peleliu worth the cost?” Many historians feel that the operation should not have been launched because the island did not pose a threat to MacArthur, as pointed out by Halsey. The Japanese simply did not have the air or naval capability to interfere with the Philippine operation from the Palaus. As events unfolded in the Pacific, Peleliu quickly became a backwater as the United States advanced toward the Home Islands.

Admiral Nimitz never commented on the operation; however, two other naval officers felt compelled to go on record. Admiral Halsey stated in his memoirs that the whole campaign was a mistake. “I felt they would have to be bought at a prohibitive price in casualties. In short, I feared another Tarawa [a small atoll in the Central Pacific that cost the Marines and sailors 3,000 casualties]—and I was right.

Noted World War II naval gunfire expert Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf said that, “If military leaders [including naval] were gifted with the same accuracy of foresight that they are with hindsight, undoubtedly the assault and capture of the Palaus would never have been attempted.”

The Point Today

The 600 inhabitants of Peleliu today live on the northwest side of the island, where a small dock for boats provides their only link to Koror, the administrative capital of the Republic of Palau. Fishing, subsistence farming, and tourism—scuba diving and battlefield tours—support the local economy.

Most of the battlefield remains relatively unspoiled. Dense scrub growth conceals the point’s battlefield relics from the casual observer. However, if one looks closely, the coral is littered with vestiges of the fighting. Relics abound in the caves, bunkers, tunnels. Ordnance litters the ground, including unexploded mortar and artillery rounds—and even Japanese hand grenades. Exploring the sites is not for the faint of heart. Shell fragments, expended .30 caliber cartridges, remnants of fighting positions—and on the edge of the 30-foot spit of land, two half-concealed concrete bunkers, still housing the Japanese 47mm antitank guns that played such havoc with the landing.

At low tide, the exposed steel treads of an amphibious tractor (amtrac) lie just 55 yards from the embrasure of the left flank bunker, mute testimony to the deadly effects of the Japanese gun. During the landing, some unknown Marine had dumped an ammunition crate, the wood long since rotted away, in the salt water. Mounds of .30 caliber rounds lie fused together in the coral, the brass shiny from being scoured with sand.

Ashore, the coral rocks teem with scuttling land crabs, trying to escape the danger of an invader’s footsteps. Except for the sound of their movement, the point is deathly quiet, a far cry from that day in September 1944 when deafening explosions and the screams of wounded and dying men reverberated across the island.

My beloved father was in K Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marine Division, First Marines and fought with distinction on Peleliu under the command of Captain Hunt. My father’s name was Francis Robert (Bob) O’Brien and he was mentioned in Captain Hunt’s book, “Coral Comes High”, written after the war had ended. My father was one of the survivors who made it through Peleliu, although he was severely wounded there when he was hit by exploding mortar shrapnel from the enemy and was knocked unconscious and his ear drums perforated from the blast. A fellow Marine was able to drag him to safety. My father also served with distinction prior to Peleliu, in both the Guadalcanal and Cape Gloucester campaigns. Sadly he passed away in the summer of 2018 at the Veterans Hospital in Tucson, AZ. at almost 96 years of age. Semper Fi to him and all the Marines of WW2.

STILL LIVING, AGE 95, HOPEFULLY A BOOK SOON ON WWII MEMORIES OF PELELIU AND OKINAWA.

Several years ago my wife’s cousin came to visit and brought her late father’s footlocker so I could help her figure out what he had, get his service record, etc. I had known he – PFC Manley Harrison – was a Marine, but in going through the footlocker, then doing some more research, I learned that he was not only 1st Marines, but was in K Company who survived The Point. Knowing that, handling his web gear sent chills up my spine.

For the rest of his life, he had to sleep in a separate room from his wife. The nightmares were too bad.

You do not mention the US Army had to bail the Marines out. My dad was there US Army Wild Cat Division.

“Bail out the marines???”. Everybody deserves credit but the marines were the tip of the spear.

Hardest fight of all the landings, with the highest casualties. Known as the Bitterest Battle, and criticized for being unnecessary due to the island’s low strategic value. For me this is the US Marine’s finest day.

Quite correct and based on contemporary information. Japanese troops had been moved to Luzon and the Visayas. Peleliu was over 700 miles from the nearest Japanese air field of any consequence at Davao. The Japanese navy was in a poor position to resupply the island and could have been interdicted by an American naval force half the size of the invasion force. The island could easily have been blockaded. As it turned out, the US did land on the western side of Mindanao in 1945 and marched to Davao where they found a rather small Japanese force which was defeated in a series of comparatively brief actions. My late wife and her family were internal refugees who stayed with the guerillas during the war but they would not have been able to return to Davao any earlier as MacArthur had changed the planned landing area to Leyte. None of this diminished the bravery of those who fought at Peleliu and probably forewarned of the Japanese intention of no surrender in Okinawa and probable fighting on the home islands. This was an obvious factor in the decision to use the atomic bombs to finally end the war.

Super article details are right on

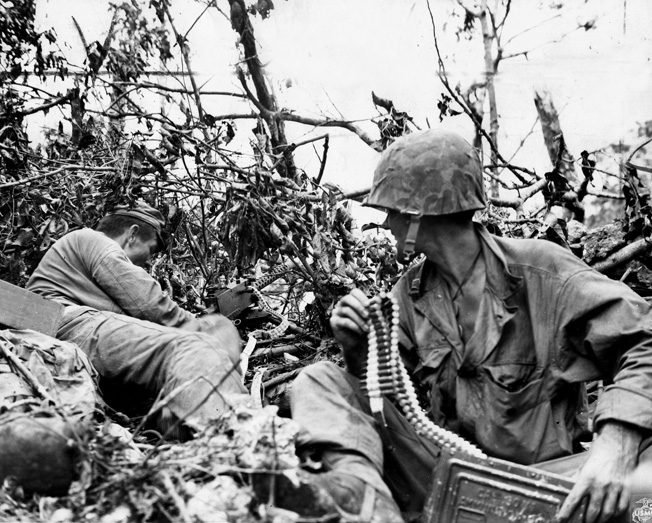

The “Marine firing his Thompson” is my Grandfather PFC Robert F. Schubert #-334437. I have the book that he signed his name on that photo. I don’t know much about his time in the war as he passed when I was ten. He never talked much about it (not to me anyway), but would love to see if there is any info on him anywhere.

The photo of the Marine firing his Thompson, that was my Grandfather PFC Robert F. Schubert. I have a few picture colorized and a book with signature of him.

Dad was in 2nd platoon had a bullet go in front of helmet and out the side. On this battle he was Assistant BAR Huffman was BAR Murray was team leader and Darling was tapped for stretcher duty. So this team was short. Late in the day Dad, Huffman and Bandy and another made their way to Hunt CP surviving the night. Hit with mortar fragments Hunt sent him through the gap to the medics they sent him out with all wounded. The night of D day was hand to hand combat. Platoon leader Lt Woodyard was hit and died immediately right in front of dad. Only 9 or 10 of 2nd platoon were rescued out of the tank trap around 6 that night. They were sent up by boat the next morning to help Hunt. It was a brutal battle