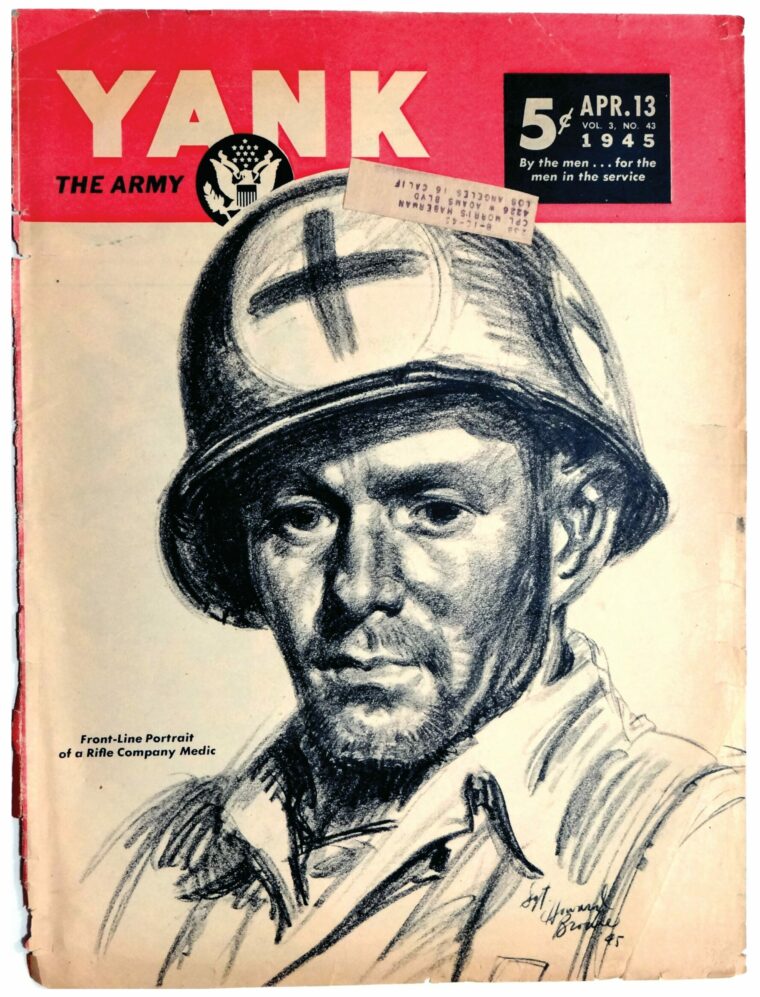

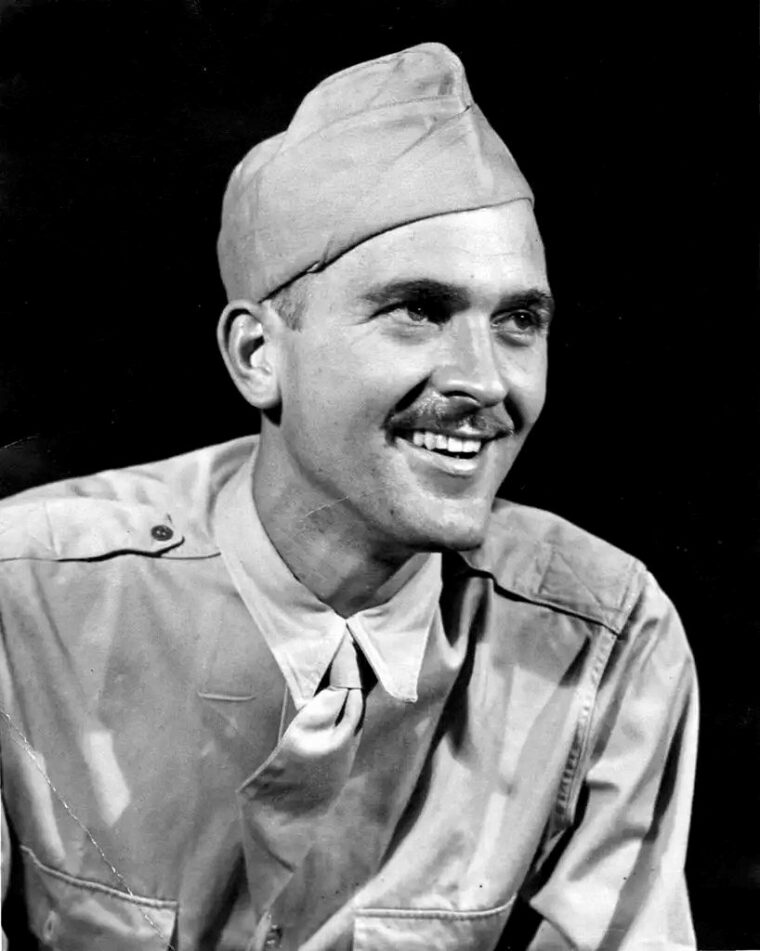

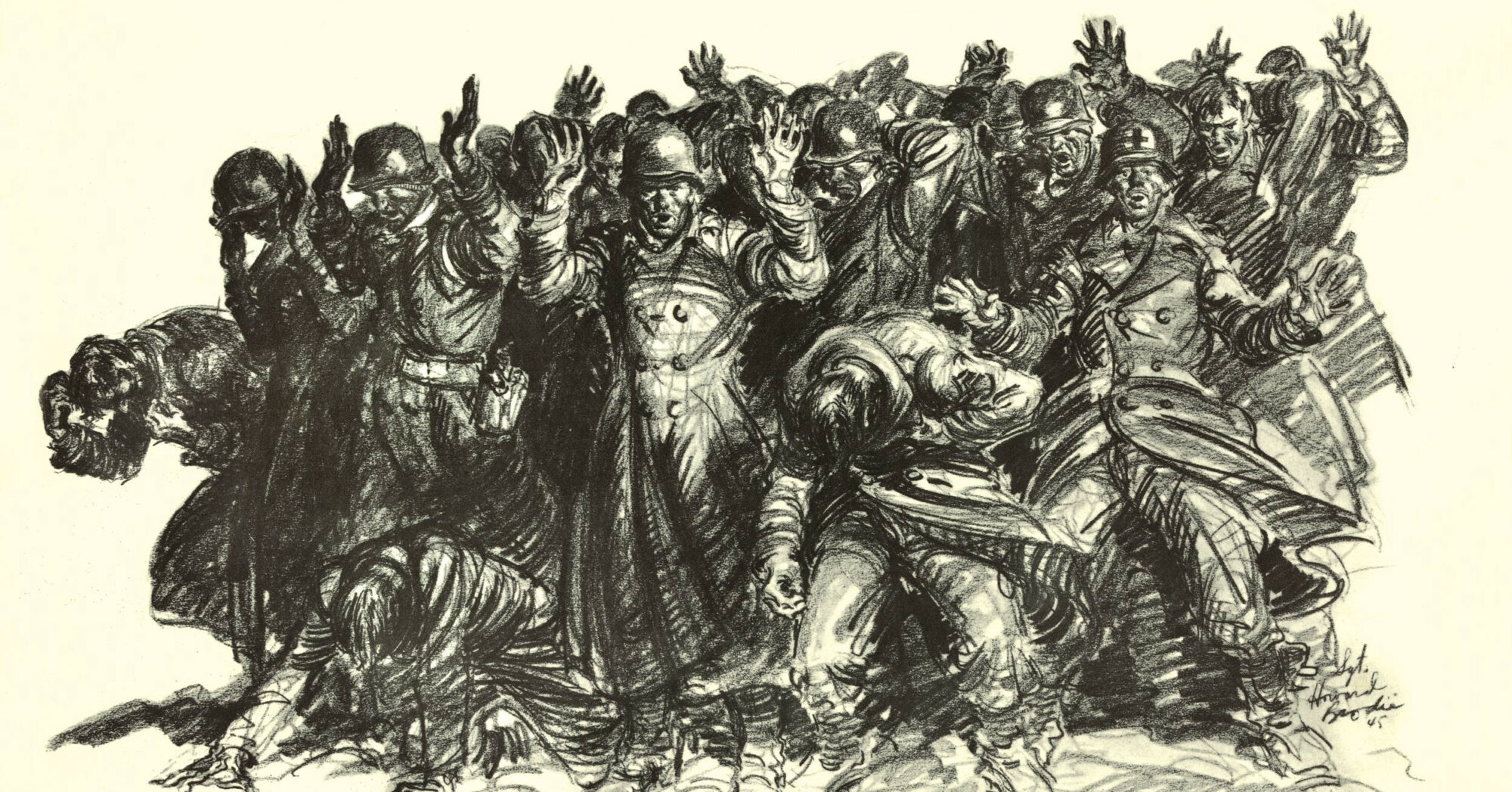

By Howard Brodie

Newspaper artist Howard Brodie enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1942, soon joining the combat artist program. He was sent by Yank magazine to capture his impressions of the war with a pencil during the Guadalcanal campaign and then the fighting in Europe. One observer of his work wrote, “By capturing emotions on the field with fluid lines and attention to detail, Brodie’s work is honest and at times, harrowing, but this honesty established him as one of the top news artists of his time.

In February 1945, he had been assigned by Yank to accompany K Company, 406th Regiment, 102nd Infantry “Ozark” Division, as they approached Germany’s Roer River. This is his report.

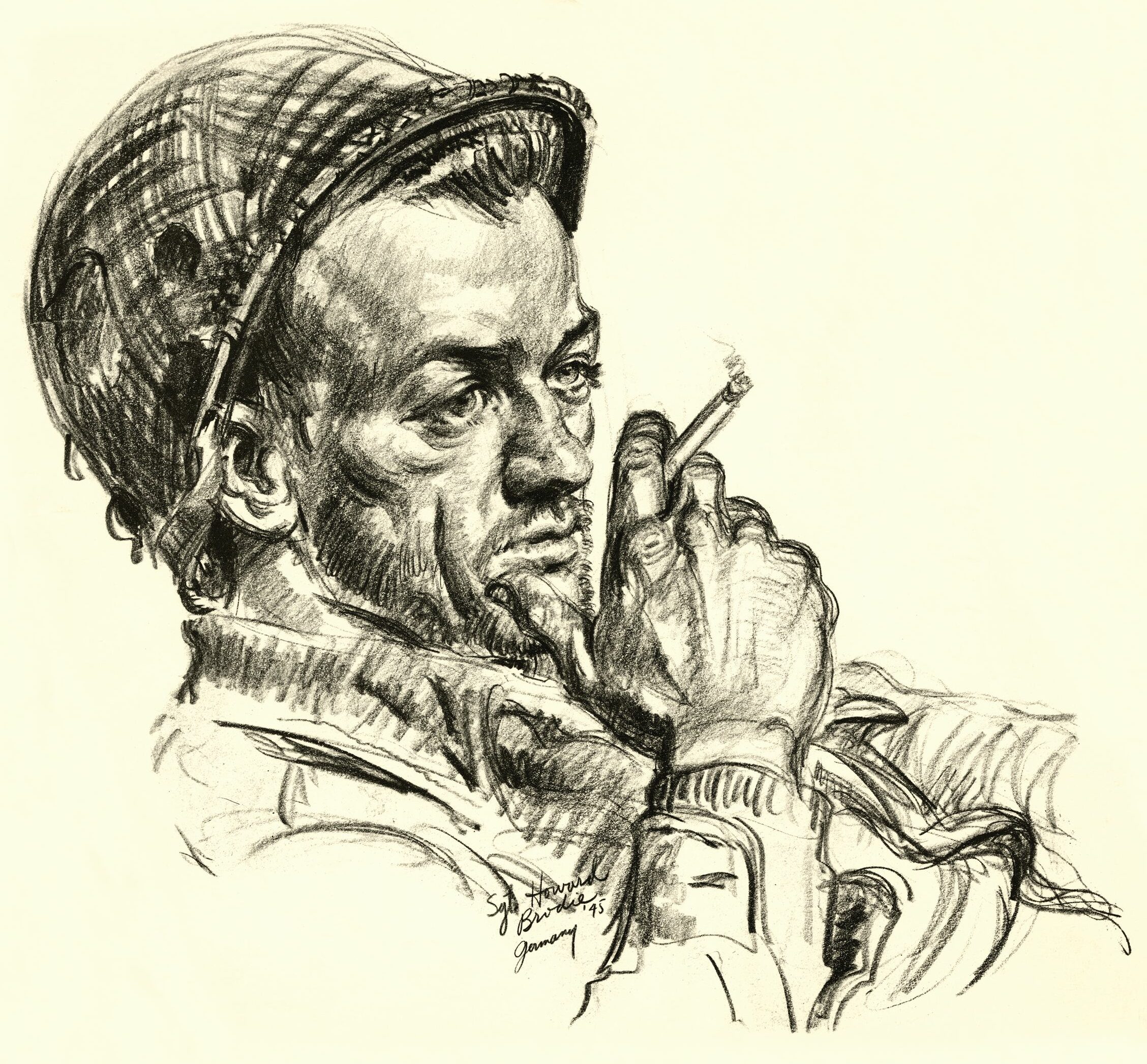

I felt every one of us sweated it out as we went to sleep that night. At 0245 our barrage awoke us, but we stayed in our sacks until 0440. After hot chow we saddled our packs and headed for an assembly area in a wrecked town about five miles away. It was a silent company of men spaced on either side of the road—the traditional soldier picture of silhouettes against the crimson flashes of shells bursting on the enemy lines in the distance.

In the assembly town, we waited in the shattered rooms of a crumbling building. It was not pleasant waiting, because a dead cow stank in an adjoining room. We shoved off at daylight and came to gutted Rurdorf. I remember passing crucifixes and a porcelain pee pot on the rubble-laden road and pussy willows as we came to the river. A pool of blood splotched the side of the road. We crossed the Roer on a pontoon bridge and moved on. The forward elements were still ahead of us a few miles.

We passed a still doughboy [U.S. soldier] with no hands on the side of the road; his misshapen, ooze-filled mittens lay a few feet from him. Knots of prisoners walked by us with their hands behind their heads. One group contained medics. In their knee-length white sacks, emblazoned with red crosses, they resembled crusaders. In another group were a couple of German females, one of them in uniform. Mines like cabbages lay on either side of the road.

We entered the town of Tetz and set up the CP in a cellar. Two platoons went forward a few hundred yards to high ground overlooking the town and dug in. We were holding the right flank of the offensive finger. Several enemy shells burst in the town. Some tracers shot across the road between the CP and the dug-in platoons, seemingly below knee-level. Night fell.

The CP picked up reports like a magnet: “The Jerries are counterattacking up the road with 40 Tiger tanks…. “The Jerries are attacking with four medium tanks.” Stragglers reported in from forward companies. One stark-faced squad leader had lost most of his squad. The wounded were outside, the dead to the left of our platoon holes. It was raining. I went to sleep.

The next day, I went to our forward platoons. I saw a dough bailing his hole out with his canteen cup … saw our planes dive-bomb Jerry in the distance … saw our fire burst on Jerry, and white phosphorous and magenta smoke bombs. I saw platoon leader Lieutenant Joe Lane playing football with a cabbage.

I saw a dead GI in his hole slumped in his last living position—the hole was too deep and too narrow to allow his body to settle. A partially smoked cigarette lay inches from his mouth, and a dollar-sized circle of blood on the earth offered the only evidence of violent death.

Night fell and I stayed in the platoon CP hole. We didn’t stay long, because word came through that we would move up to the town of Hottdorf, the forward position on the offensive finger, preparatory to jumping off at 0910.

K Company lined up in the starlit night—the CO, the 1st Platoon, MGs, the 3rd Platoon, heavy weapons, headquarters, and the 2nd Platoon in the rear—about 10 paces between each man and 50 between the platoons.

The sky overhead was pierced by thousands of traces and AA bursts as Jerry planes flew over. Again, it was a silent company.

At Hottdorf we separated into various crumbling buildings to await H-Hour. We had five objectives, the farthest about two and a quarter miles away. All were single houses but two, which were towns of two or three houses. We were the assault company of the 3rd Battalion.

H-Hour was approaching. A shell burst outside the window, stinging a couple of men and ringing our ears. We huddled on the floor.

It was time to move now. The 1st Platoon went out on the street followed by the MGs and the 3rd Platoon and the rest of us. We passed through doughs in houses on either side of the street. They wisecracked and cheered us on. We came to the edge of town and onto a broad, rolling field. The 3rd and 1st Platoons fanned out in front of us. Headquarters group stayed in the center.

I followed in the footsteps of Pfc. Joe Esz, the platoon runner. He had a light aluminum case upon which I could easily focus the corner of my eye to keep my position and still be free to observe. Also, I felt that if I followed in his footsteps I would not have to look down at the ground for mines. He turned to me and commented on how beautifully the company was moving, properly fanned and well-spaced.

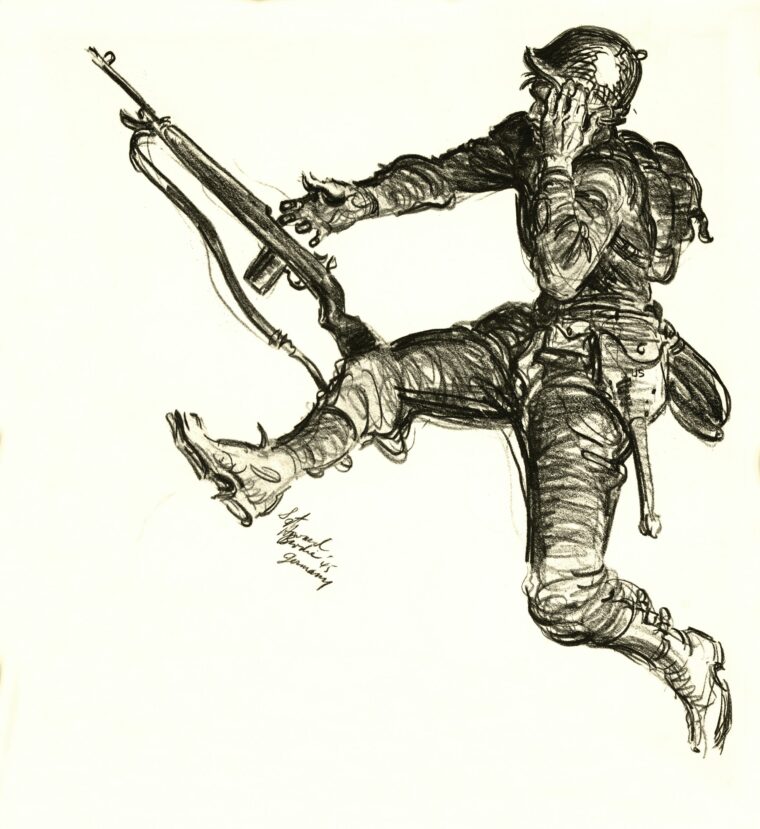

Several hundred yards away I noticed Jerries running out of gun position waving a white flag. A black puff of smoke a few hundred yards to my right caught my attention, then another closer. I saw some men fall on the right flank. The black puffs crept in. There were whistles and cracks in the air and a barrage of 88s burst around us. I heard the zing of shrapnel as I hugged the earth. We slithered into the enemy 88 position from which I had seen the prisoners run. Somebody threw a grenade into the dugout.

We moved on. Some prisoners and a couple of old women ran out onto the field from a house. Objective One. There was the zoom and crack of 88s again. A rabbit raced wildly away to the left. We went down. I saw a burst land in the running Jerries. One old woman went down on her knees in death, as though she was picking flowers.

A dud landed three feet in front of T/Sgt. Jim McCauley, the platoon sergeant, spraying him with dirt. Another ricocheted over Pfc. Wes Malden, the 300 radio operator. I looked to the right flank and saw a man floating in the air amidst the black smoke of an exploding mine. He disappeared just in front of the squad leader, S/Sgt. Elwin Miller. A piece of flesh sloshed by Sgt. Fred Wilson’s face. Some men didn’t get up.

We went on. A couple of men vomited. A piece of shrapnel cut a dough’s throat as neatly as Jack the Ripper might have done it.

The right flank was getting some small-arms fire. I was so tired from running and going down that it seemed as though my sartorius muscles would not function. The 300 radio wouldn’t work and we couldn’t get fire on those 88s. Pfc. George Linton went back through that barrage to get another [radio] from Hottdorf. Medic Oliver Poythress was working on wounded in that barrage.

Objective Two loomed ahead—a large building enclosing a courtyard. Cowshed, stables, toolshed, hayloft, living quarters opened on the inner court. I saw an 88 explode over the arched entrance.

We filtered into the courtyard and into the surrounding rooms. The executive officer started to reorganize the company. The platoons came in. First Sgt. Dick Wardlow tried to make a casualty list. A plan of defense was decided on for the building. A large work horse broke out from the stable and lumbered lazily around the courtyard. T-4 Melvin Fredell, the FO radio operator, lay in the courtyard relaying artillery orders. An 88 crashed into the roof. The cows in their shed pulled on their ropes. One kicked a sheep walking around in a state of confusion.

A dying GI lay in the tool room; his face was a leathery yellow. A wounded GI lay with him. Another wounded dough lay on his belly in the cowshed, in the stench of dung and decaying beets, and another GI quietly said he could take no more. A couple of doughs started frying eggs in the kitchen. I went into the toolshed to the dying dough.

“He’s cold, he’s dead,” said Sgt. Charles Turpen, the MG squad leader. I took off my glove and felt his head, but my hand was so cold he felt warm. A medic told me he was dead.

Lt. Bob Clark organized his company and set up defense. FO Philip Dick climbed the rafters of the hayloft to report our artillery bursts. The wounded dough in the cowshed sobbed for more morphine. Four of us helped to carry him to bed in another room. He was belly down and pleased for someone to hold him by the groin as we carried him: “I can’t stand it. Press them up, it’ll give me support.” A pool of blood lay under him.

I went to the cowshed to take a nervous leak. A shell hit, shaking the roof; I ducked down and found I was seeking shelter with two calves. I crossed the courtyard to the grain shed, where about 60 doughs were huddled.

Tank fire came in now. I looked up and saw MG tracers rip through the brick walls. A tank shell hit the wall and the roof. A brick landed on the head of the boy next to me. We couldn’t see for the cloud of choking dust. Two doughs had their arms around each other; one was sobbing. More MG tracers ripped through the wall, and another shell. I squeezed between several bags of grain. Doughs completely disappeared in a hay pile.

We got out of there, and our tanks joined us. I followed a tank, stepping in its treads. The next two objectives were taken by platoons on my right, and I don’t remember whether any 88s came in for this next quarter mile or not. One dough was too exhausted to make it.

We were moving up to our final objective now—a very large building, also enclosing a courtyard, in a small town. Jerry planes were overhead but for some reason did not strafe. Our tanks spewed the town with fire and led the way. Black bursts from Jerry time-fire exploded over our heads this time.

We passed Jerry trenches and a barbed-wire barrier. Lt. Lane raced to a trench. A Jerry pulled a cord, setting off a circle of mines around him, but he was only sprayed with mud. S/Sgt. Eugene Flanagan shot at the Jerry, who jumped up and surrendered with two others.

Jerries streamed out of the large house. Women came out, too. An 88 and mortars came in. I watched Pfc. Bob de Vaslk and Pfc. Ted Sanchez bring out prisoners from the basement, with Pfc. Ernie Gonzalez helping.

We made a CP in the cellar. The wounded were brought down. Stray Jerries were rounded up and brought to the rear. Jittery doughs relaxed for a moment on the beds in the basement. Pfc. Frank Pasek forgot he had a round in his BAR and frayed our nerves by letting one go into the ceiling.

A pretty Jerry girl with no shoes on came through the basement. Doughs were settling down now. The CO started to prepare a defense for a counterattack. Platoons went out to dig in. L and M Companies came up to sustain part of our gains.

Most of us were too tired to do much. The battalion CO sent word he was relieving us. All of us sweated out going back over the field, although this time we would go back a sheltered way. We were relieved and uneventfully returned to a small town. The doughs went out into the rain on the outskirts and dug in. A few 88s came into the town.

Early the next morning, K Company returned to its former position in the big house with the courtyard as the final objective. Just when I left, Jerry started counterattacking with four tanks and a company of men.

This article by Howard Brodie originally appeared in Yank magazine, Vol. 3, Number 43, April 13, 1945.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments