By Jamie Malinowski

Early in the morning of July 8, 1942, in the calm waters of Caballo Bay south of Corregidor Island in the Philippines, a casco, a 12-foot by 60-foot flat-bottomed wooden diving barge, bobbed placidly in the open water 120 feet above the ocean floor. Standing on its deck was a workforce consisting of 25 men, give or take a couple, an unusual group thrown together by war and opportunity.

On board were Captain Hiro Takiuti, a young Japanese Army engineer who was placed in overall command; Kunichi Yosobe, a middle-aged Japanese civilian salvage expert who had lived many years in the Philippines and whose job it was to manage the operation; and a half-dozen Japanese soldiers, headed by a kempei tai, a large and temperamentally sadistic military policeman whose job was to maintain discipline and whose preferred method was force.

The majority of the laborers consisted of eight Filipino men, pumpers who worked the machine that supplied deep sea divers with the oxygen vital to their continued existence. At one point not long before, eight such divers, Filipino men, had been present on this very barge, but after three of them died sudden and excruciating deaths the rest quit, the kempei tai’s threats notwithstanding.

Now, rounding out the group, were six new divers. Veterans of the crew of the USS Pigeon, a submarine rescue ship, the men had survived the grueling siege of Corregidor and six harrowing weeks in a succession of prison camps, the last being the notoriously brutal and disease-ridden Cabanatuan, north of Manila. One day they were assigned to the seemingly benign Takiuti, who said he needed divers to help clear Manila Bay of sunken vessels.

The men were happy to have been chosen, relieved to be out of the brutal camp, delighted to be eating reasonably well for the first time in months, and heartened by slightly improved hopes of escape. At the same time, the Americans agonized over the thought that they might be giving aid and assistance to such a hated enemy. This was especially true if, as they suspected, the task had nothing to do with sunken ships and everything to do with sunken treasure.

Diving For the Casco’s Sunken Treasure

Aboard the casco, Yosobe explained that, in fact, they would be salvaging sunken cargo and showed the divers the equipment available to them to get the job done. It was a terribly inadequate array: there were several helmets, all designed for diving in shallow water no deeper than 30 feet; a couple dozen suits of heavy diving underwear; superannuated air hoses whose ability to withstand sea pressure and to continuously conduct oxygen to the divers far below the surface was highly suspect; and an ancient hand pump whose capacity to force air on a sustaining basis to a diver at the end of a dodgy umbilical cord 120 feet underwater seemed dubious at best.

The divers complained about the age and near uselessness of the equipment, but discussion was pointless. The Japanese did not have anything better and were not going to invest any time looking for upgrades, so the Americans faced a Hobson’s choice. It was either dive with substandard equipment or return to the malnutrition and disease and beatings of Cabanatuan. In reality, there was no choice. Only one option presented an upside. Cooperation offered more of a chance of living; cooperation held out the possibility of hope. The divers said yes.

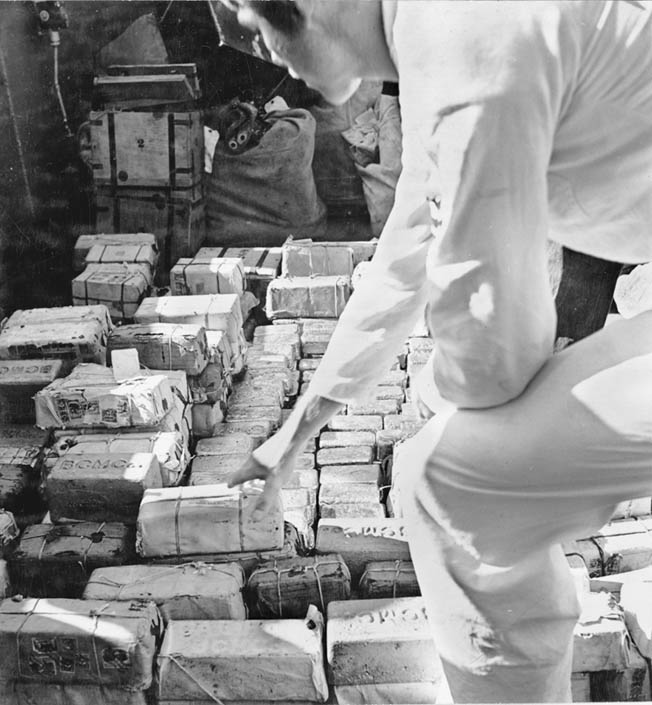

Boatswain’s Mate Virgil Sauers, nicknamed Jughead, was the first to dive. He put on his helmet, connected his air hose and lifeline, and began to lower himself into the water. It was warm at first, but as he slowly descended the sea grew darker and colder. After a while, however, the ocean floor slowly came into focus and the sunken cargo Yosobe had broadly described became more distinct. It was a pile of boxes, 14-inch by 14-inch by 24-inch wooden crates, dozens of them. Most were intact, but many had cracked open, jarring the canvas bags that were inside, loosening the ties that bound them. Spilling from the bags were coins, silver coins, scores and scores of them, hundreds of them, thousands, worth in all likelihood millions of American dollars.

The Destruction of the Philippines Treasury

The coins that Sauers saw on that morning were not the ancient relics of Spanish traders or Chinese pirates, but were part of the treasury of the government of the Philippines and had been placed on deposit in Davy Jones’ locker only two months before. The fortune had been on the run since late December, after General Masaharu Homma’s invasion forces had reached the outskirts of Manila. Just before the government of President Manuel Quezon declared the capital an open city, the treasury was the subject of a dramatic, Dunkirk-like evacuation to Corregidor.

Beleaguered treasury department clerks loaded millions of dollars worth of gold and silver bullion, paper money, bearer bonds, treasury certificates, coins, jewels, and foreign currency into boxes, bags, filing cabinets, footlockers, and other receptacles. These containers were then hauled to the docks and dumped onto the decks of a makeshift flotilla that included tugs, barges, U.S. Navy and U.S. Army vessels, and the presidential yacht Casiano, which carried the valuables across the 27 kilometers of Manila Bay to Corregidor, where they were deposited in a large underground complex called the Malinta Tunnels.

There the loot sat until early February, when the submarine USS Trout became one of the few ships to slither through the Japanese blockade, delivering 3,500 much-appreciated rounds of antiaircraft ammunition. In need of ballast for its return trip, the empty Trout then took on two tons of gold bullion and 18 tons of silver pesos from the volcanic vault and sailed for Australia.

Meanwhile, conditions on Bataan and Corregidor deteriorated. Food was rationed, ammunition grew scarce, and the promised relief force never materialized. On March 11, under orders from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, General Douglas MacArthur evacuated the islands. Four weeks later, on April 9, the American and Filipino forces on Bataan surrendered, which freed the Japanese to concentrate all their firepower on Corregidor, whose defenders were gallant but utterly bereft of air or sea defenses. Realizing that surrender was both inevitable and imminent, General Jonathan Wainright ordered the destruction of everything of value—ammunition, weapons, documents, and, of course, the treasury of the Philippines.

A raging bonfire took care of the paper money and government securities; seldom had people with money to burn rid themselves of it so joylessly. But that left between 14 and 17 million silver pesos, each about the size of a U.S. silver dollar and worth about 60 cents in American money, with a total weight of 390 tons.

The treasure would have to be sunk. Caballo Bay was the obvious choice, since Corregidor’s own mountains would shield the dumping operation from the bulk of the Japanese forces positioned north of the island. Army officers selected the spot for the salty depository by drawing lines that connected landmarks on the opposite shores of Manila Bay; the X of their intersection would mark the spot, a deep and choppy area that would discourage salvage efforts if this scheme ever came to light.

Starting at dusk on April 26, the Harrison, an old Army minelayer that was one of the few vessels left to the American command, began dumping pesos, 2,000 coins to a bag, three bags to a 300-pound box, two men to manhandle a box into the drink. The 42-man crew worked through the night in as much silence as they could maintain, their exertions illuminated by the flashes of guns and explosions of shells as the Japanese dismantled Corregidor’s defenses. After six nights, the men dropped the last of the 2,630 boxes overboard. Three days later, the island surrendered.

Japan’s First Diving Efforts

Hopes that the dumping operation would remain secret quickly proved fruitless, and Captain Takiuti, the young engineer, was assigned the task of recovering the loot. A request to the Imperial Navy for divers was rebuffed; not only did the Navy, with its emphasis on professionalism, generally disdain the more political, more ideological Army, but it already had a job for its divers: rescuing the 500-foot-long Dewey Dry Dock that had been scuttled in Subic Bay.

Undeterred, Takiuti had Yosobe hire local divers, veterans of salvage work in Manila harbor, but none of whom, alas, had experience working at depths greater than 30 feet. Utilizing some full diving suits they had located, the Filipino divers made their first forays into the depths of Caballo Bay on May 27; on the second dive, a box was located and brought up to the casco. Using his sword, Takiuti pried open the box and slashed the bags. When the pesos spilled out, he and Yosobe exuberantly shouted, “Banzai!” By nightfall, two more crates had been brought up.

The next day, two more cases were recovered, although by the time the second one made it to the deck of the casco the headaches that some of the divers had begun experiencing the previous evening had begun to afflict all of them, only with greater intensity and accompanied by nausea and intense fatigue.

What the divers were experiencing was the bends, or decompression sickness, which arises as divers come out of deep water when dissolved gases inside the body turn into bubbles as the body undergoes depressurization. Since bubbles can form in and move throughout any part of the body, decompression sickness can produce a variety of symptoms of varying severity and can change from day to day. At its worst, however, the pain is agonizing and the condition lethal, and generally speaking, the deeper one has dived and the faster one has emerged, the more severe the condition. The divers had no firsthand experience of the bends, but they had heard of divers becoming sick this way and they were alarmed.

On the third day, the symptoms in one of the divers intensified, and he collapsed. His colleagues treated him with hours of massage, and after a while he recovered. This emboldened the Japanese, who were now able to dismiss the divers’ complaints as minor afflictions that could be ameliorated with a little massage. But to calm concerns, the Japanese gave the team a day off.

The next day, two divers collapsed in intense pain. Massage therapy proved unavailing, and the stricken divers were transported to a hospital in Manila, where they died. When this news was reported back to the casco, most of the rest of the divers immediately quit.

“You Know What They’re Really After. Don’t Let Them Get it.”

All but one. His conclusion was that the men were not getting an adequate supply of air. He proposed dispensing with the diving suit and using only the shallow water diving helmet. This contraption, which consists of a helmet attached to a weighted breastplate that helps sink the diver, focused the air in the helmet.

At first, this adaptation produced results. More boxes were recovered, and the diver felt no symptoms of the bends. Unfortunately, the diver’s inexperience soon caught up with him in another way. Because the helmet and breastplate are not actually attached to the body, American divers who had used the equipment had run the air hose and a lifeline from the surface under their armpit, a technique that prevented the helmet from floating off or being pulled away. The poor Filipino did not think of this, and the next day while on the floor of the sea the helmet became separated from the man. He was never seen again.

By then, Takiuti had 18 boxes, about 100,000 pesos, and no divers. With a heightened appetite and no alternatives, he turned to the U.S. Navy.

Six divers, Sauers, Morris “Moe” Solomon, Wallace A. “Punchy” Barton., P.L. “Slim” Mann, George McCullough, and Charles Giglio, were pulled out of the prison population at Cabanatuan and sent to Manila. Even before they left, they suspected that the Japanese might be calling on them to recover the sunken silver and sought the advice of their commanding officer, Lt. Cmdr. Frank Davis.

“You know what they’re really after,” he said. “Don’t let them get it.” Their suspicions were whetted further when on the train trip to Manila they were given pork sandwiches and cigarettes and then housed in a clean room where each had a cot and locker. This was a lot better than Cabanatuan. In some ways, it was even better than Corregidor!

A Purposefully Slow Pace

By the end of the first day, three dives had been made, and two boxes holding about 12,000 pesos had been recovered. More importantly, the divers had acquired enormous amounts of information about the details of the operation. Yes, the casco was anchored near a mountain of boxes, but nothing that a competent diving crew would not have cleaned up in a few weeks. And not only did the Japanese not know how concentrated the pile was, they had no idea about the condition of the boxes.

While the diving equipment was indeed ancient and decrepit, air pressure was so weak inside the helmet that water seeped in past the divers’ chins, meaning that the men could never bend their necks without putting their faces underwater, this and their captors’ general ignorance about the principles of diving and decompression worked to their advantage. The Americans were the experts. The Japanese were the ones who had seen three divers die. If the Japanese wanted the silver, they were going to have to do things the way the Americans said they had to be done. Which meant slowly.

From the beginning, the divers decided to give the Japanese just enough to keep them happy. The silver was spread around a fairly large area, but within that area much of it was concentrated into a pile. The Japanese did not know that, and the Yanks did not tell. Instead, they stacked the deck, working out an arrangement in advance that some dives would end productively and some would be shut out.

The Americans also limited the amount of time they would spend on the sea floor to 15 minutes, established decompression breaks on their way up, and cancelled dives when the water currents or weather conditions turned unfavorable. This meant that each diver was performing about one dive a day, apart from Giglio, who was so inexperienced that his comrades refused to let him dive at all and instead left him in charge of maintaining their quarters. He proved very adept at this. Takiuti allowed the Americans to scrounge the American positions in Corregidor, and over time they found typewriters, a radio, pistols, grenades, and many creature comforts, including carpeting that had been in MacArthur’s office.

Theft as Sabotage

The Americans slowed the pace in another way—sabotage. Boxes that were intact could be moved rather efficiently; the diver just tied a line to the box, and the men on the casco would haul it up. A broken box, holding damaged bags, could hardly be moved at all. The pesos had to be transferred to another container. A diver’s allotted 15 minutes might tick off before he harvested many coins. The other problem with loose coins, of course, is that some of them might not find themselves into a Japanese-approved receptacle at all. Some might find themselves in the sole of a diver’s shoe or slipped inside his diving underwear.

As time went on, the Americans grew more brazen. Punchy Barton dropped a line that had a marlinspike at the end off the side of the boat; the tool dangled in the work area and made it easy to crack open the boxes. On the dives that had been preordained to be empty-handed, the diver spent his time cracking open boxes with the spike. Soon Moe Solomon figured out how to make bags from the legs of worn out dungarees. These, too, were then attached to a line and dropped off the casco. Over several shifts, each succeeding diver would help fill it. When at last the bag was full, the diver tugged on the dangling line 10 times—not a signal likely to be missed or misidentified—and while one man brought the bag up the others on deck formed a screen that hid him from the guards. There were perhaps a thousand pesos in each haul.

Then there came a day when the kempei tai was confronted with the theft. Punchy Barton had just come out of the water and was removing his helmet when his belt became loose and about a dozen pesos fell to the deck. Neither Takiuti nor Yosobe were close enough to see what had happened, but Barton was standing right in front of the kempe tai. Staring Barton in the eye, he rose from his chair and approached the diver, a nasty scowl predicting his intentions.

By the standards of the Cabanatuan prison camp, a beating was surely in order, and worse could not be ruled out. But once the kempei tai got face to face with Barton, he emitted a low, nasty laugh, bent over, and picked up eight of the coins. Then, with a grunt, he turned back to his seat, leaving the other Japanese soldiers to scramble to pick up the rest of the pesos.

formerly residing in the Philippine Treasury. In the spring of 1942, the valuable treasure was removed from Manila, the capital city of the Philippines, to prevent its falling into the hands of the Japanese.

More Divers For the Task

After a month, Yosobe decided that he needed to pick up the pace and added three more Navy divers, George Chopchick, Holger Anderson, and Bob Sheats, whose memoir One Man’s War: Diving as a Guest of the Emperor, 1942 is a source for much of the information about these events. As more pesos were recovered, the Americans were given more latitude. Relations eased between the Americans and some of the Japanese, notably Takiuti’s second in command, who even arranged conjugal visits with local women for some of the prisoners.

On their scavenging expeditions, the divers often met other POW work crews, and they were able to slip pesos to them that were used to buy food and medicine for Americans festering in the camps. They also met a Filipino woman who turned out to be the widow of one of the divers who died trying to recover the pesos. She worked in Takiuti’s office and was able to share the intelligence she gathered with the men. Most dramatically, she was able to warn the Yanks that a surprise inspection of their quarters had been scheduled. The men had just enough time to hide their contraband silver and weapons before their lodgings were tossed.

The beginning of the end of the American escapade came in September, when Yosobe, intent on increasing production, hired Moro divers to augment his crew. Although they professed that they hated the Japanese and loved America, and although they seemed to grasp why the Americans were moving at such a slow pace, the Moros went to work and began pulling up the pesos at a rapid rate.

One day soon after they started, the Moros, working on a separate casco with some excellent British diving equipment, pulled up 18 boxes, far, far more than the Americans had ever accomplished.

“They have better equipment!” protested the Americans when the Japanese asked why. It was an accurate explanation, but not a correct one, and the Yanks soon realized that they were in grave danger of losing their jobs to more effective workers.

On September 29, a storm brewed up. Anticipating a typhoon, Yosobe halted operations and packed up the men and equipment and sent them to safety. En route to the harbor in Manila, the Americans noticed that they had all been placed on one boat, where they were being watched by two crewmen and an alcoholic soldier who had been nicknamed the Drunkard. For a moment they considered trying to overpower the guards and escaping, then rejected the idea of trying to get away during a typhoon. But then they also noticed that in the haphazard scheme of things, their boat was towing the Moro casco.

Once the Drunkard slipped into his customary stupor, the Americans loosened the bridle. Soon the Moro casco flipped over, dumping the competition’s superior equipment into the bay. A little further loosening of the towline allowed the casco to separate and slip away. When the Drunkard roused himself, he was overcome by shame and remorse and tried to kill himself by jumping into the harbor. He was stopped by the Americans, who were acting under the assumption, probably correctly, that they would have been accused of murdering him.

3.5 Million Pesos Remain in the Caballo Bay

For whatever reason, on November 7, the Japanese stopped the recovery efforts. Final tallies showed that about an eighth of the 16 million pesos had been recovered, 18 boxes by the Filipinos, 97 boxes by the Americans, 257 by the Moros.

The prisoners were assigned to other salvage operations, although in keeping with their moral calculus that prevented them from raising ships that could be used against the Allied war effort they acted only as pumpers, not as divers. After the laissez-faire Takiuti was suddenly replaced by a far less tolerant officer, the Americans’ liberty was curtailed, and in February 1943, after refusing to return the salute of a visiting Japanese general, they were all returned to POW camps. Apart from Chopchick, who was killed when American planes bombed a Japanese ship on which he was being transported, they all survived the war.

Over the years, much of the fortune has been recovered. A U.S. Navy operation collected about six million pesos in 1945, and an American salvage crew working for the Republic of the Philippines found 2,800,000 more in 1947. But in an article published in 2007, numismatics expert Timothy B. Benford speculated that as much as 3.5 million pesos could still be scattered on the floor of Caballo Bay.

During my time in the Philippines, 1977-79, working as a civilian employee of the US Government, I heard many treasure stories from the locals. There were numerous tales of various locations of buried or sunken treasure and there were a number of ill financed and equipped expeditions to locate the rumored treasures. As I remember, about the most anyone ever found were a few scattered coins and some rusty inoperative weapons. If there is any left to be found, it certainly seems quite hidden.

A most interesting article, well written.