By Patrick J. Chaisson

Battleships,” said Adolf Hitler, “have had their day.”

In a military conference held December 29, 1941, Hitler took time to remind those in attendance that not so many months ago the Bismarck went down with all but 115 of her 2,200 crewmen after a 100-hour sea battle. More recently, he added, two British capital ships—Prince of Wales and Repulse—were sunk by Japanese torpedo planes off Malaya.

To the commander-in-chief of Nazi Germany’s armed forces, it no longer made sense to maintain a large fleet of surface vessels. The immense amount of resources required to construct, man, and fuel these warships, Hitler felt, could better be used elsewhere—such as in the vast land campaign against Soviet Russia.

Grand Admiral Erich Raeder listened to his Führer’s words with great concern. Raeder, who commanded the Kriegsmarine (German Navy), had devoted the last 14 years to building a seagoing force capable of challenging Great Britain’s powerful Royal Navy (RN). His goal was to achieve what the German Imperial Navy in World War I could not do: wrest control of the Atlantic Ocean and starve Britain into submission.

Raeder did not accomplish this ambitious task, however, as the Kriegsmarine never launched a sufficient quantity of new battleships and fast cruisers capable of overcoming its adversaries’ potent fleets. And those German surface vessels that did sail into harm’s way were often outmatched by the RN’s superb tactics, precision gunnery, and aggressive torpedo aircraft.

For some time now, Admiral Raeder had the decidedly uncomfortable feeling that Adolf Hitler was marginalizing him. He watched helplessly as the Führer, a man completely unschooled in naval theory, began taking direct control of Kriegsmarine operations. In the German Navy (as well as the Army and Air Force), sound military logic was being replaced by one man’s intuition.

In May 1941, following Bismarck’s demise, Hitler directed his surface fleet to adopt a “no unnecessary risk” policy. Germany’s capital ships could not attack a vessel of equal or larger size, nor were they to enter combat if a large enemy force was known to be near. All battleships and cruisers required his personal authorization to leave port and were expressly prohibited from venturing into the Atlantic Ocean. Lastly, Kriegsmarine warships had to depart the area of operations any time a British aircraft carrier was reported nearby.

Suffering under these onerous restrictions were three of Nazi Germany’s most powerful capital ships: the battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau along with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen. Docked at the French harbor of Brest for nearly a year, these vessels endured almost daily air attacks by Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF). During that time, several lucky bomb and torpedo hits resulted in hundreds of casualties as well as extensive battle damage to all three warships.

Known as the “Twin Sisters,” Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were the first capital ships built as part of Nazi Germany’s pre war rearmament program. Launched in 1936, each battlecruiser (a British term—the Germans considered them battleships) measured 741 feet, 6 inches at the waterline and displaced 38,700 tons when fully loaded. Capable of 31 knots, these vessels enjoyed a 6,000-mile combat range.

Both Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were armed with a main battery of nine 11-inch guns housed in three turrets. Their secondary armament included another 12 5.9-inch pieces, as well as a suite of antiaircraft weapons and six torpedo launchers. Plans existed to fit them with 15-inch cannon, but these modifications never occurred.

Each warship had an authorized complement of 1,669 men—56 officers and 1,613 enlisted sailors. Captain Kurt-Caesar Hoffmann commanded Scharnhorst, while Captain Otto Fein skippered Gneisenau.

On March 22, 1941, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau entered the French port of Brest after concluding a successful mid-Atlantic raid. They were joined there on June 1 by the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen. With an overall length of 697 feet, this 19,050-ton warship could run at speeds exceeding 32 knots. Prinz Eugen mounted eight 8-inch guns in her main battery, along with twelve 4.1-inch cannon and six torpedo tubes as secondary armament. Commanded by Captain Helmuth Brinkmann, her company numbered 42 officers and 1,340 enlisted hands.

Less than a week before, Prinz Eugen had narrowly escaped a series of British naval attacks that sank her consort, the battleship Bismarck. Arriving at the well-equipped Brest dockyards for repairs, her appearance alongside Scharnhorst and Gneisenau was quickly noticed by French operatives. This information was then passed on by radio to British Naval Intelligence.

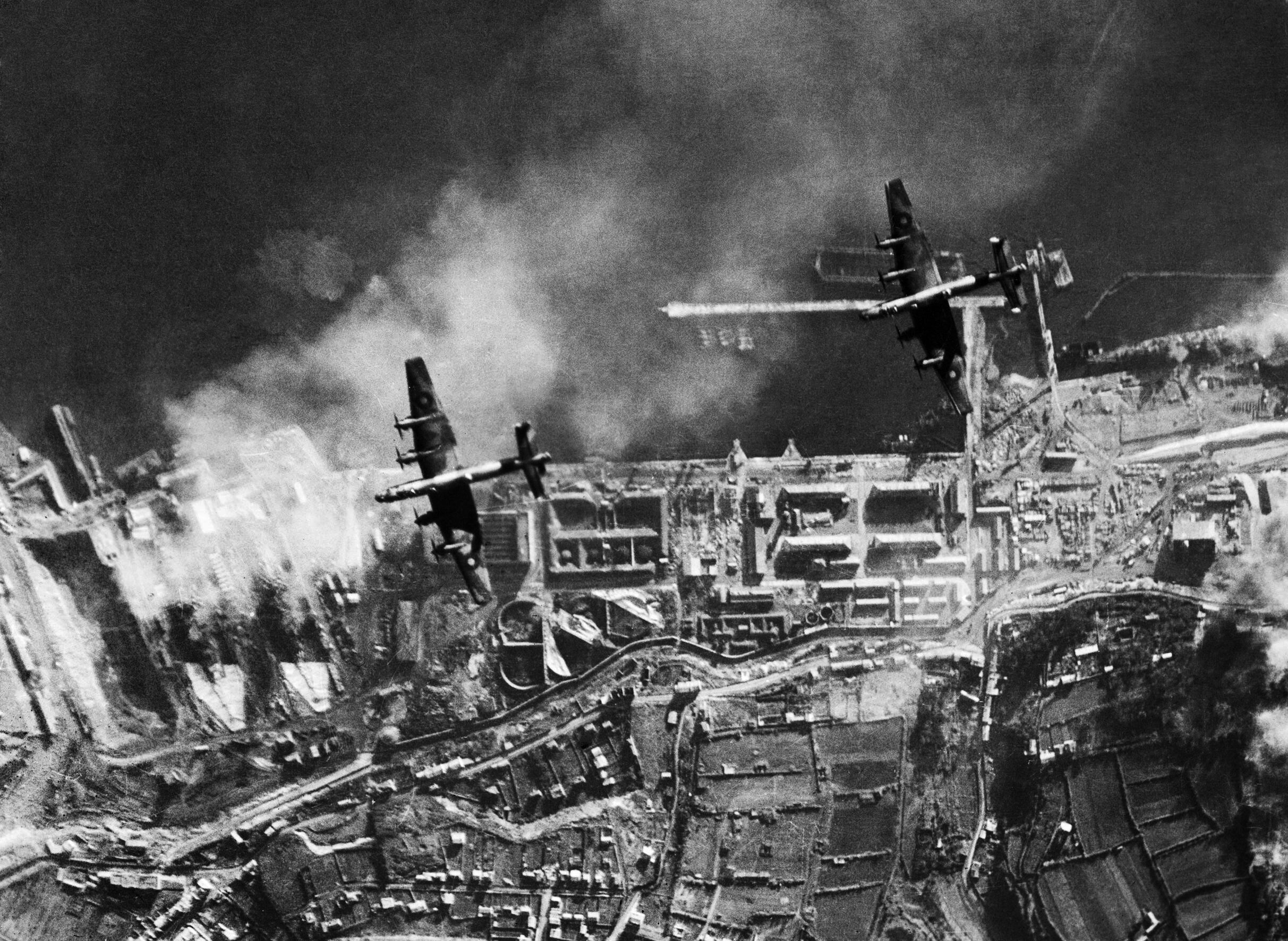

Royal Air Force bombers struck just eight days later, initiating a months-long air campaign against what flight crews jokingly called “The Brest Target Flotilla.” Between August 1 and December 31, 1941, British airmen dropped 1,200 tons of bombs over Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen. This effort, which resulted in several direct hits on all three vessels, also killed or wounded over 200 seamen.

Despite the RAF’s near-constant attention, Admiral Raeder argued there was great value in keeping these warships based at Brest. There, they acted as a “fleet-in-being” that forced British naval commanders to keep on hand a substantial reaction force—ships and planes badly needed elsewhere in a global war that now included Japan as an adversary.

Yet, Hitler had his own thoughts on the future of Germany’s surface fleet. On December 29, 1941, the Führer summoned Raeder to his underground “Wolf’s Lair” headquarters near Görlitz, East Prussia, to share these ideas. Fearing an Allied invasion of Norway, Hitler declared that nation as a “Zone of Destiny” and demanded the Kriegsmarine send all available capital ships to Norwegian waters. This order included the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen.

He then considered how these vessels could make their escape from France. “Only a bold run through the English Channel under advantageous weather conditions,” Hitler said, would enable the Brest group to redeploy safely. He then told Raeder that if this Kanalmarsch (Channel march) failed, all three warships were to be decommissioned and their guns turned over to the coast artillery.

Hitler went on to say that Germany now had to use its resources more purposefully, even suggesting that the time for capital ships had passed.

Admiral Raeder knew his Führer’s comment about scrapping the mighty Brest group and repurposing its guns into coastal defense weapons was no idle threat. Shaken, he departed the Wolf’s Lair determined to produce a comprehensive plan for that force’s voyage. There was much Raeder and his staff needed to consider.

First, when would Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen be ready to sail? Assuming they did not suffer any additional damage from RAF bombs, all three vessels could be put to sea not earlier than January 31, 1942. Next, an analysis of the moon and tides pointed to the period of February 11-15 as most favorable for a breakout providing the weather cooperated.

Even though Hitler favored a passage through the Straits of Dover, Raeder felt duty bound to present all alternatives. The Channel transit did have its advantages: a short route, good air and sea escort possibilities, and adequate emergency harbors. Mitigating these factors were the difficulties of navigating and maneuvering in the English Channel’s shallow waters, as well as the presence of enemy destroyers, torpedo boats, and strike aircraft. Sea mines, both German and British, posed another major threat.

Admiral Raeder preferred a longer track, one that passed around Ireland’s west coast and through the Denmark Strait to reach friendly harbors. This scheme risked an encounter with the RN’s Home Fleet at Scapa Flow, but allowed the German vessels more open-ocean maneuver room. Raeder and his staff wanted to keep their “fleet-in-being” where it was, but the Denmark Strait option promised better chances for survival should Hitler insist on redeploying the warships based at Brest.

Raeder outlined these planning considerations in a memo to the Führer dated January 8, 1942. In this document he predicted the Brest group would likely suffer total loss, or at least heavy damage to the ships and their crews should it attempt a run through the English Channel. “I therefore see myself according to my innermost conviction not in a position to propose such a transfer operation,” he concluded.

Yet, the admiral understood from long experience that once Hitler determined on a course of action, little could be said to change his mind. Resigned to the inevitable, Raeder and several subordinate naval commanders traveled to Görlitz on January 12 for a coordination meeting regarding the Kanalmarsch.

Also in attendance at the Wolf’s Lair were Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, chief of Germany’s armed forces; General Alfred Jodl, his chief plans officer; General Hans Jeschonnek, Luftwaffe Chief of Staff; and Colonel Adolf Galland, Inspector of Fighters in France and the man responsible for providing air support over the Brest group during its journey. The conference began once Hitler took his seat.

Vice Admiral Otto Ciliax, who would command the Brest group’s breakout, spoke first. A long-serving battleship veteran, Ciliax enthusiastically outlined his plan of action. It emphasized security: no shakedown cruises were authorized, as any unusual pre-deployment activity would surely alert enemy spies or reconnaissance aircraft. The task force was to depart at night, relying on surprise and the Luftwaffe for protection as it made a mid-day run through the Straits of Dover. By passing over deep water most of the way, Ciliax said, his warships might avoid most known British minefields.

This drew comment from Commodore Friedrich Ruge, who commanded the mine-sweepers charged with clearing Ciliax’s path. Ruge reported encountering sophisticated new sea mines that defied his trawlers’ best efforts to detect and remove them. He could not guarantee safe passage through these obstacle belts.

Speaking for the Luftwaffe, Jeschonnek promised 250 fighters to achieve local air superiority. He also committed 25 or so night fighters that would keep enemy dawn patrols at bay. Jeschonnek further detailed a highly classified radar jamming capability designed to reduce the chances of British forces detecting Ciliax’s command during the critical first hours of its voyage.

Hitler had the final word. He acknowledged the naval force at Brest diverted enemy bombers from making attacks upon the Fatherland but went on to say the British naval response would be identical regardless of where Germany’s surface fleet was stationed. The strategic situation, he stated, now required all available warships in operation off Norway.

Likening the Brest group to a cancer patient, Hitler claimed these vessels were “doomed without an operation.” He recognized that the Kanalmarsch came with great risk but observed, “…an operation, even if it’s a drastic one, offers at least some hope of saving the patient’s life. The only possibility is a surprise breakthrough with no previous indications that it is to take place. We need total surprise—and a bit of luck to boot.” He added, “Most of my decisions have been bold, and only those who accept the dangers deserve luck.”

Then Hitler announced, “I have determined to withdraw the ships from Brest.” With that statement, the Kanalmarsch became a formal mission. All naval activity fell under the code word Operation “Cerberus,” while the Luftwaffe’s portion was titled Operation “Donnerkeil” (Thunderbolt). Cerberus would commence at 2030 hours on Wednesday, February 11, 1942.

The assembled air and naval commanders efficiently addressed all necessary coordinating details in an uncommon display of interservice cooperation between the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. For instance, it was arranged that each of Admiral Ciliax’s capital ships carry on board an Air Force communications team responsible for direct tactical control of the aerial covering force.

The German Navy took extraordinary measures to mislead British Intelligence, whose network of French informants kept a close eye out for any unusual activity in and around the port. Supplies of tropical uniforms were conspicuously delivered to each warship, while invitations to a large costume ball set for 12 February in the city of Brest went out to all enlisted sailors. None of these seamen knew that by then the fleet would be long gone for decidedly non-tropical waters.

Commodore Ruge’s minesweepers started clearing and marking pathways along the Brest Group’s route, doing so only at night so as not to alert British patrols. Additionally, a pair of specially modified Heinkel He-111 bombers began operating along the Channel coast with powerful transmitters on board jamming Britain’s air and surface radars. This was done gradually so enemy technicians would not immediately notice the signal interference.

These operational security measures did not completely mask all preparations for the breakout. For some time, Britain’s service chiefs recognized their adversary might attempt to redeploy its Brest Group through the English Channel. To discuss this possibility, Adm. Dudley Pound, Chief of Naval Staff, met regularly with his RAF counterparts, including Bomber Command chief Air Vice Marshal Jack Baldwin and the head of Coastal Command, Air Chief Marshal Philip Joubert.

Their response, developed in great secrecy at the highest level of command, was code named “Fuller.” Operation Fuller called for synchronized attacks by Admiral Pound’s small flotillas of destroyers and motor torpedo boats (MTBs), vessels well suited for the Channel’s shallow waters, acting in concert with several squadrons of RAF Bristol “Beautorp” strike aircraft. Another six RN Fairey Swordfish torpedo planes, reconstituting after the Bismarck campaign, could also be called upon if necessary.

Bomber Command allocated 300 warplanes for the operation, although RAF flight crews knew the odds of hitting a moving ship with unguided iron bombs were abysmally low. Available as a covering force were nearly 400 Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire fighter planes.

In addition, several Lockheed Hudson patrol aircraft provided electronic early warning with their onboard air-surface radar systems. Finally, the 9-inch coastal batteries positioned near Dover could range far into the Channel—although good visibility was needed in order for these guns to adjust fire.

Meanwhile, the port of Brest hummed with activity as Ciliax’s task force prepared to conduct its Channel Dash. Workmen feverishly completed repairs to Gneisenau following a bomb hit on January 6 that flooded two compartments. Then, on the morning of February 11, all non-Germans were removed from the dockyard area and the harbor sealed off.

The officers and crewmen aboard Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen—most of whom were totally unaware of what was about to happen—went about their normal duties that day. Earlier, however, Ciliax gathered together his ships’ captains for a conference on board Scharnhorst.

There, the task force commander outlined Operation Cerberus. At 2030 hours, his capital ships would slip their moorings and join six accompanying destroyers for the planned 30-hour transit to port facilities in Kiel and Wilhelmshaven, Germany. Other escort vessels would rendezvous with the Brest group as it sailed up the Channel coast. Continuous Luftwaffe air cover was set to commence at dawn.

“It is a bold and unheard-of operation for the German Navy,” Ciliax said of his plan. “It will succeed if [my] orders are strictly obeyed.”

By 2030 hours on February 11, the fleet stood ready to cast off. Just then, though, air raid sirens across Brest began to sound. A flight of RAF Vickers Wellington medium bombers passed overhead, dropping their loads well clear of the port. Admiral Ciliax waited impatiently for the “all-clear” signal; finally, at 2214 hours, his task force received permission to proceed.

The Brest group got underway around 2245 hours, led by Destroyer Z29. Then, in line-astern formation, came Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen. Once clear of the harbor, two more destroyers deployed on each flank while Z25 fell into the rear. Ciliax and his ships’ captains anxiously checked their watches—Operation Cerberus was already more than two hours behind schedule.

Most junior officers still did not know their destination. On Scharnhorst’s bridge, Officer of the Watch Wilhelm Wolf asked his ship’s navigator for the course to steer. Helmuth Giessler called for a starboard turn to 340 degrees. Wolf questioned this heading, as it would take the ships into the English Channel. “The course is correct,” Giessler smiled. “Tomorrow you’ll be at home with your wife.”

Making 29 knots, the Brest group passed Ushant by 0200 hours and entered the Channel. At 0212 hours, Admiral Ciliax informed his ships’ companies by loudspeaker about the mission’s true purpose: “The Führer has summoned us to new tasks in other waters,” he began, indicating their difficult mission would demand a supreme effort from every man. “The Führer expects from each of us unwavering duty,” he closed. “It is our duty as warriors and seamen to fulfill these expectations.”

The sun rose seven hours after Ciliax’s warships started their run. The weather, initially characterized by broken clouds and a moderate sea state, began to worsen. Decreasing visibility, along with growing westerly winds, a heavy swell, and intermittent rain squalls, served to conceal the task force as it closed the Cherbourg Peninsula at 0630 hours.

The Luftwaffe appeared around this time. Following a precise plan crafted by Colonel Galland, at least 16 but often many more day fighters flew broad figure-eight patterns over the Brest group. Four schwarme (flights) of four fighters each—one low, one high, one to the east, one to the west—provided continual air cover for 30 minutes at a time before moving on to a forward airstrip where they refueled and rearmed. Ready again for patrol, the fighters then resumed escort duties in accordance with Galland’s carefully organized timeline.

A total of 252 Messerschmitt Me-109s and Focke-Wulf Fw-190s participated in Operation Donnerkeil, as the air operation was known. Three full Jagdgeschwader (JG- fighter wings): JG 1, JG 2, and JG 26, as well as the Paris fighter school cadre, maintained dawn-to-dusk coverage. Messerschmitt Me-110 and Junkers Ju-88 night fighters also supported the breakout.

Gerhard Krumbholz, a Ju-88 pilot on dawn patrol, described the Brest group—now swollen to 60 vessels by the addition of auxiliaries and patrol craft—as it looked from his cockpit: “Majestically and calmly they move through the turbulent sea, surrounded by numerous security vessels, destroyers, and minesweepers. Motor torpedo boats hunt protectively on all sides. Often the boats nearly disappear in the heavy breakers. German fighter planes circle over the naval unit heading for the narrow Channel. [Our] hearts… beat faster.”

So far as Krumbholz could tell, though, the Channel Dash was proceeding unopposed. “The Tommies,” he remembered, “appear to be asleep.”

Plagued by poor planning assumptions, bureaucratic inertia, and plain bad luck, the British reaction to Admiral Ciliax’s daring Kanalmarsch unraveled rapidly. The senior officers who prepared Operation Fuller strongly believed their opponents would never attempt a daylight run through the Channel, and thus did not pay close enough attention when the Brest group weighed anchor during the evening hours of February 11.

An S-class submarine, HMS Sealion, was stationed off Brest to provide early warning of enemy activity but shifted position after midnight to recharge her batteries and missed the task force’s passage. Equipment failures onboard three radar-equipped Hudson bomber aircraft patrolling the region enabled Ciliax’s command to escape detection a second time.

At 1042 hours on February 12, two Spitfire pilots spotted the German fleet off Dieppe. Under orders to maintain radio silence, though, those aviators did not report their sighting until after they had landed. Further time was wasted in notifying Fighter Command, whose duty officers replied they were only interested in enemy aircraft and not ships.

When news of the breakout finally reached naval headquarters in Dover, someone remembered the top-secret contingency plan and removed it from an office safe. Contacting the London-based Air Ministry, that officer barked the word “Fuller” through his telephone to activate the order. Incredibly, the person on the other end said “there is no one of that name here” and hung up.

An excessive focus on secrecy crippled the British reaction. Even after RN and RAF commanders began to grasp the problem at hand, more bad news arrived. A squadron of Beautorp strike aircraft was grounded by snow in Scotland, while six Harwich-based destroyers were on exercise at sea and needed to proceed at flank speed through friendly minefields if they stood any chance of intercepting the foe.

Individual commanders went into action using whatever assets were at hand, hoping to (in the words of a post-battle report) “delay the enemy in any way possible by immediate attack with any force available [rather] than risk losing the opportunity in the effort to arrange coordinated attacks.”

At Manston airfield, Lt. Cdr. Eugene Esmonde received orders to take his No. 825 Naval Air Squadron’s six Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers aloft against the Brest group. These twin-winged aircraft, capable of just 115 knots at full throttle, required a large escort if they were to penetrate Galland’s aerial shield. Royal Air Force liaison officers promised five fighter squadrons in close support, but only 10 Spitfires materialized as Esmonde’s “Stringbags” neared the German fleet at 1245 hours.

The Swordfish flew into a buzzsaw. Three planes went down before they could launch their payloads; Esmonde and his two wingmen managed to drop a “fish” (all of which missed their target) but were then shot out of the sky. Thirteen of 18 aircrewmen perished, including Lt. Cdr. Esmonde.

A few minutes later, four MTBs from Dover made an extreme-range torpedo attack on the Brest group; no warships were struck. Another three boats out of Ramsgate dueled with the German rear security detachment from 1320 hours to 1400 hours. These vessels could not get past the enemy’s destroyers and returned to base without firing their torpedoes.

At 1318 hours, coastal artillery batteries at Dover opened up on the task force as it sailed by. All 36 rounds fell short, and the gunners could not see well enough in the gathering murk to adjust fire. Moving at 28 knots, the Brest group passed out of range at 1333 hours.

So far, the Kanalmarsch was going better than most Kriegsmarine officers could have hoped. This changed at 1432 hours when Scharnhorst struck a mine near Ostend, Belgium. The massive battlecruiser shuddered to a halt and lost all electrical power, prompting Ciliax to transfer his flag to a nearby destroyer. By 1450 hours, however, emergency repairs had been made and Captain Hoffmann called for maximum available speed in an attempt to catch up with the fleet.

The six elderly destroyers (Campbell, Vivacious, Worcester, Mackay, Whitsed, and Walpole) under Captain Mark Pizey’s command had been running at full steam toward the Brest group since 1145 hours. It was a risky maneuver, though, involving passage through an unmarked British minefield. Indiscriminate air attacks by RAF Hampden bombers only added to Pizey’s woes.

Sometime after Walpole fell behind due to mechanical issues, the remaining five warships deployed on line and pressed in. From his flagship, HMS Campbell, Captain Pizey sighted enemy vessels dead ahead at 1542 hours. He immediately ordered a torpedo attack.

In response, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen opened fire with their main batteries. Escorting Luftwaffe fighters also dropped down to strafe the British warships. HMS Worcester, last in line, got the worst of it. Prinz Eugen delivered multiple broadsides that shattered her boiler rooms, ripped off half the bridge, and killed or wounded more than 100 sailors.

On board Gneisenau, Captain Fein “watched our heavy guns score direct hits on the English destroyer.” His report continued: “It seemed to me that she heeled so far over under the impact that she nearly capsized. I ordered our guns to cease fire, as there seemed no point in wasting shells on a ship already sinking.”

According to Fein, no vessel that size could endure such a heavy pounding. Yet somehow Worcester’s surviving crewmen managed to keep their destroyer afloat, plugging holes and relighting her engines for a hazardous overnight return to Harwich. Worcester’s sacrifice came to nothing, however, as all torpedoes fired by Pizey’s gallant little flotilla missed their targets.

For hours, RAF Coastal Command struggled to coordinate a cohesive attack by its Bristol Beautorp strike aircraft. Bad weather and even worse luck conspired against this effort. While some warplanes remained snowbound in Scotland, others flying in from Cornwall waited for hours while torpedoes were located, moved to the proper airfield, and mounted. Poor coordination and appalling weather forced RAF officers to send up their Beautorps one or two at a time, with negligible results.

Bomber Command sortied 242 warplanes in three waves on the afternoon and early evening of February 12. Heading out singly or in pairs, their flight crews braved Luftwaffe fighters, antiaircraft fire, and low visibility over the Channel. The results were disappointing: only 39 aircraft actually dropped on the Brest group, sinking one small gunboat for 22 RAF bombers shot down or gone missing.

Operation Fuller had failed miserably. One British air commander, commenting on his flight crews’ experiences that day, said: “They often did not know where they were going and what they would be firing at. Coordination was a joke, communications a farce, and fighter cover unavailable.”

As the winter sun set, most of Ciliax’s force was off Ijmuiden, the Netherlands. Scharnhorst, intent on rejoining the main body, steamed at 27 knots about 30 minutes behind her sister ship and its escorts. At 2055 hours it was Gneisenau’s turn to detonate a mine, which opened a hole in her starboard side and disabled the center turbine. Still able to proceed at 15 knots, she limped into the port at Kiel together with Prinz Eugen and several smaller vessels shortly after sunrise.

In the meantime, Scharnhorst reported hitting another magnetic mine off the Frisian Islands at 2234 hours. Damage control parties quickly shored up the damage, though, and by noon on February 13 she was safely docked inside Wilhelmshaven harbor. Shortly thereafter, Ciliax reported to Kriegsmarine HQ the successful completion of Operation Cerberus.

The Germans suffered remarkably few casualties during this action. Only one vessel—the patrol craft V1302 John Mahn—was sunk, while two torpedo boats and a destroyer sustained damage from British bombs. Some 17 Luftwaffe airplanes were shot down, while the casualty count totaled 37 sailors and airmen.

British losses greatly outnumbered those of the enemy. Three dozen RAF aircraft, plus six RN Swordfish torpedo planes, never returned to base. One destroyer, the Worcester, and an MTB had been badly damaged. The list of killed, wounded, or missing exceeded 250 fighting men.

For his role in leading No. 825 Squadron’s torpedo attack on the Brest group, Lt. Cdr. Esmonde posthumously received a Victoria Cross, the United Kingdom’s highest award for military valor.

The Channel Dash became a propaganda triumph throughout Nazi Germany and a source of public embarrassment for the government of Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Hitler gained further proof of his infallible intuition, while three capital ships intended for Norway’s defense had made it to German ports. For their leadership during the Kanalmarsch, Ciliax and the Scharnhorst’s Captain Hoffmann each received a Knight’s Cross. Oddly, the captains of Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen were not similarly honored.

The British press excoriated its military for allowing an enemy surface force to transit the English Channel, something that had not been accomplished for 350 years. “Nothing more mortifying to the pride of our sea power had happened since the seventeenth century,” scolded one editor. Another (misinformed) newspaperman asked why “did no British naval patrol engage with [the German fleet as it passed through the Straits of Dover?]”

Some people blamed Prime Minister Churchill for the disaster. These accusations grew louder after February 15, when it was learned the British bastion of Singapore had fallen to Japanese troops. “This was the…blackest week since Dunkirk,” wrote one Ministry of Information official, adding, “The main weight of public criticism seems to be directed against the government.”

Admiral Raeder, who retired from active service in 1943, later claimed the Channel Dash resulted in “a tactical success but a strategic defeat” for the Kriegsmarine. No longer did the Royal Navy need to cover Brest, Raeder noted, while RAF bombers could now focus on targets inside the Third Reich. Regarding Norway, the Allies never did stage an invasion there. Hitler’s intuition had failed him.

Ultimately, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen contributed little to the German Navy’s combat record following their bold Kanalmarsch. On February 26, 1942, Gneisenau suffered catastrophic damage in a British bombing raid, later to be scuttled as a block ship in 1945. Scharnhorst went down during the Battle of the North Capes in December 1943, taking all but 35 souls on board under the waves with her.

Only Prinz Eugen survived the war. Following V-E Day she was turned over to the Americans, who used her as a target ship for atomic tests off Bikini Atoll. It marked an ignominious end to Erich Raeder’s dream of an all-powerful Nazi surface fleet.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired military officer and historian based in Scotia, New York. He is a frequent contributor to WWII History on a variety of topics.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments