By Patrick J. Chaisson

Major Robert B. Yates arrived at the 1111th Engineers’ headquarters in Trois-Ponts, Belgium, around 13:30 on Monday, December 18, 1944, expecting to sit in on an ordinary staff meeting.

Instead, he found himself thrust into command of a desperate defense against powerful German armored forces. For the past two days, these marauding SS tanks had been rampaging throughout the Americans’ rear area in a frenzy of blood and terror. Now it was Trois-Ponts’ turn to feel their wrath.

Yates hurriedly reviewed his situation. To oppose this impending onslaught, the 175 lightly-equipped U.S. combat engineers holding Trois-Ponts had on hand exactly eight “Bazooka” rocket launchers. Their meager complement of crew-served weapons totaled six .50-caliber and four .30-caliber machine guns. There were no mortars, artillery or friendly tanks available to provide support. Major Yates could expect nothing in the way of reinforcements, and all communications lines with higher headquarters had been cut. He was on his own.

As Yates considered these facts, the distinctive roar of TNT detonating signaled a renewed German assault on Trois-Ponts. Summoning all his courage, he set off to lead the fight.

At 6’3” and 200 pounds, “Bull” Yates had worked as a builder in Harrison County, Texas, before the war. The former National Guardsman had risen steadily up the ranks to executive officer of the 51st Engineer Combat Battalion (ECB), First U.S. Army.

As he prepared to face the German onslaught, he was also AWOL from an American field hospital. Yates had spent the past three and a half months impatiently recovering from a motorcycle accident that crushed his right foot. According to battalion lore, one day he just cut the cast off his leg, “borrowed” a jeep, and drove out to Marche-en-Famenne, Belgium, where the 51st ECB was based. Bull Yates, still walking with a limp, had returned to duty just three days earlier.

At the time, his outfit was running at least 32 sawmills as part of First U.S. Army’s winterization program. Those troops performing this unglamorous but essential mission produced thousands of board-feet of lumber per day for use as bridging materials or building frames. To carry out their chores, the 51st ECB’s 650 soldiers were spread out in small groups over a 30-mile work zone.

While arduous, the lumbering operation had its benefits. The men slept indoors, enjoyed regular hot meals, and felt secure in the knowledge that their duties put them 25 miles behind the front lines. Best of all, they were no longer building bridges—a hazardous, exhausting job that had been the 51st ECB’s main function all summer as the unit helped speed First Army’s advance across France and Belgium.

Meanwhile, Yates spent his first day back to work assessing the battalion’s status—where its three engineer companies ran their sawmills, their logistical requirements, and anything else that was on the 51st’s task list apart from cutting wood. Those assignments typically included road maintenance, bridge repair, and snow removal.

He also learned his higher headquarters—the 1111th Engineer Combat Group (ECG)—was led by Colonel H. Wallis Anderson, a man Yates knew well from Stateside service. Anderson’s primary mission was to coordinate the activities of four engineer battalions located throughout First Army’s sector. On Saturday, December 16, he and his small staff of officers, NCOs, and enlisted technicians maintained their command post inside the Hôtel Crismer, at a small Belgian village called Trois-Ponts.

Unknown to anyone in the 1111th, some 1,600 German artillery pieces had opened a devastating barrage on U.S. forward positions beginning at 05:30. This bombardment heralded the start of Hitler’s Operation Watch on the Rhine (Wacht am Rhein), better known as the Battle of the Bulge.

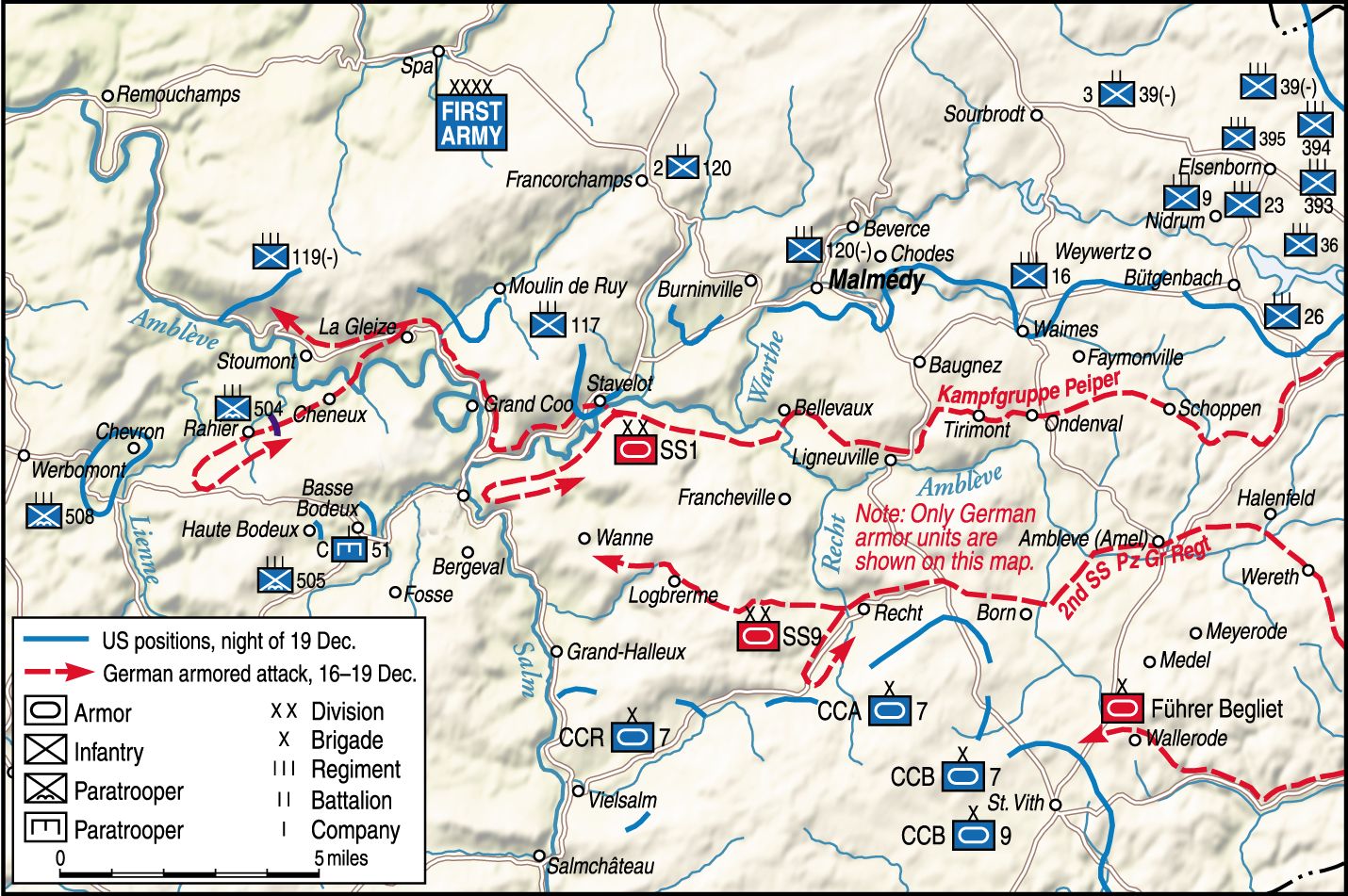

The Germans’ most powerful mechanized formation was Sixth Panzer Army, led by SS General (Oberstgruppenführer) Josef “Sepp” Dietrich. As the operation’s main effort, this command had to push aside all Allied defenses in its zone of attack, move swiftly across the Ardennes’ poor road net, and seize a number of bridges spanning the Meuse River near Liege, Belgium. Dietrich’s goal was to reach Liege—halfway to Antwerp, his ultimate objective—within 48 hours.

At the tip of Sixth Panzer Army’s armored spear was a battle group (Kampfgruppe) belonging to the 1st SS Panzer Division. This 4,800-man task force consisted of 117 medium and heavy tanks accompanied by mechanized infantry, artillery, and mobile antiaircraft guns. It was named for the officer in command: SS Lt. Col. (Obersturmbannführer) Joachim Peiper.

Peiper seemed well-qualified to lead Sixth Panzer Army’s exploitation force. An ardent Nazi, he embodied the spirit of audacious action and ruthless devotion to duty demanded of every Waffen-SS fighting man. A veteran of service on the Eastern Front and in Normandy, his aggressive, even reckless tactics had twice earned him the Knight’s Cross along with Adolf Hitler’s personal congratulations.

His reputation as an individual who got things done regardless of cost or consequences likely led to this assignment as commander of Sixth Army’s “point” (spitze). Yet Peiper’s designated route of march appalled him. “The roads were suitable for bicycles and not tanks,” he observed afterward. The SS panzer leader also requested bridging equipment be attached to his Kampfgruppe but was denied these assets. Army headquarters figured a lightning-fast advance would result in all necessary river spans falling into German hands before the enemy could fortify or destroy them.

Just prior to the December 16 assault, Peiper issued orders to his subordinate commanders. “You will go ahead at full speed,” he admonished them. “There will be no stopping for anything.” He concluded his remarks with a warning familiar to those SS officers who had served with him in Russia: “It is not the job of the spearhead to worry about prisoners of war…. Armed civilians will be treated as partisans.” In other words, they were to be shot on sight.

Peiper hoped to start his run for the Meuse before dawn on December 16, but a combination of unexpectedly heavy resistance, enormous traffic congestion, and soggy, nearly-impassable roads caused many frustrating delays. It wasn’t until after midnight that his 16-mile-long column finally began moving forward.

The route that Peiper’s battle group followed through the Ardennes Forest on Sunday, December 17, consisted of paved main highways, soft-surfaced secondary roads, and even narrow firebreak trails. From their starting point at Losheim, Germany, his tanks proceeded steadily all morning through the Belgian towns of Honsfeld and Büllingen, flushing coveys of disorganized U.S. service troops along the way.

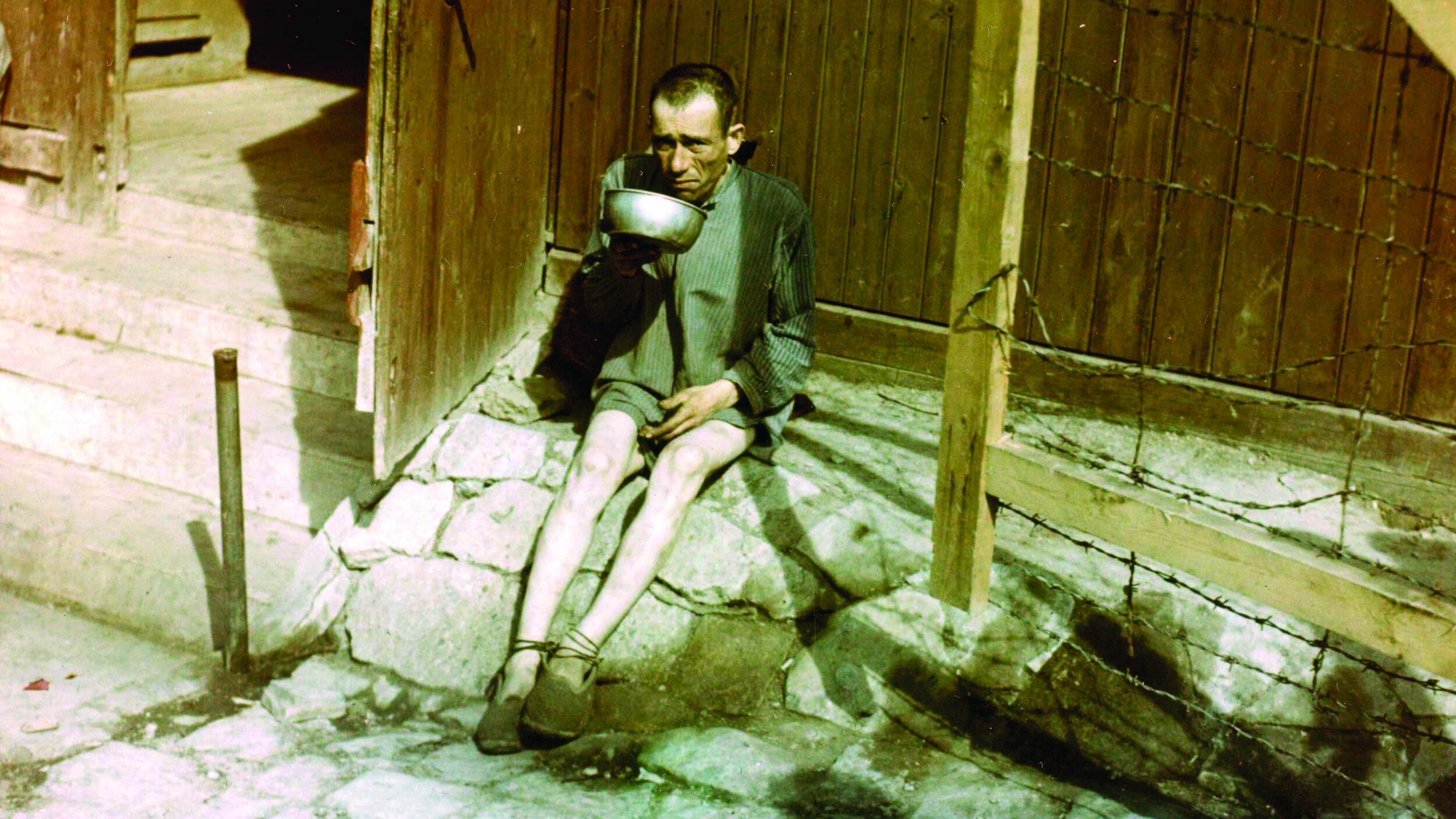

That afternoon at a small road junction named Baugnez, members of Peiper’s command gunned down 84 surrendering G.I.s — the “Malmedy Massacre” — just one of many atrocities committed by his men against helpless prisoners of war and innocent Belgian civilians.

Farther west, at Ligneuville and Stavelot, the Germans’ forward progress was slowed by small groups of defiant American soldiers who were literally buying time with their lives. In fact, 13 combat engineers blocking the road into Stavelot made so much noise that Peiper— convinced he was up against a large and tenacious enemy defensive force—halted for the night.

While Peiper and his SS panzers had traveled 30 miles in 18 hours, 50 miles still separated them from their objectives on the Meuse. Yet it now appeared they would have to fight for the Amblève River bridge at Stavelot. Disturbingly, another set of timber trestles—just four miles down the road in Trois-Ponts—also needed to be seized intact. Kampfgruppe Peiper did not possess the time, the bridging equipment, or the fuel supplies required to bypass this key crossroads.

Another man who understood the importance of Trois-Ponts was Colonel Anderson, who on December 17 occupied that small hamlet together with his 1111th ECG headquarters staff. Anderson also realized these clerks, radiomen, and technical specialists plainly lacked the weapons and training necessary to defeat tanks. But his practiced eye saw one clear solution to the coming crisis.

A road, rail, and river junction, Trois-Ponts sat at the confluence of the Salm and Amblève Rivers. The Salm, some 30 feet wide, coursed northward through town and joined with the larger Amblève flowing west from Stavelot. While both watercourses could be waded by foot soldiers, tracked vehicles were unable to ford due to sharp riverbanks. Steeply-sloped ridges loomed over the settlement on all sides and restricted mechanized movement primarily to narrow valley roadways.

Trois-Ponts received its name for the three highway bridges that provided entry from the north, south, and west. Two trestles—one in the village center and the second two miles south of town—crossed the Salm River, while another—some 500 yards north of Anderson’s HQ building—spanned the Amblève. Several railroad viaducts and light footbridges, all capable of supporting dismounted infantry but not heavy armor, also required attention.

Anderson knew that whoever possessed the town’s three highway bridges controlled access to the entire area. He and his staff tracked Kampfgruppe Peiper’s route throughout the day on December 17, concluding that Trois-Ponts had to be its next objective. “We must stop the enemy,” Anderson declared, “and we must stop him here.” But how?

Appeals to First Army for infantry or armored support all went unanswered. Furthermore, Anderson had already sent away his two closest combat engineer battalions—most of the 291st ECB was now in Malmedy and a company of 202nd ECB engineers occupied Stavelot. Smaller detachments, scattered all across the region, had either been swallowed up by the foe or were bravely standing guard over lonely crossroads and bridge sites.

Twenty miles away in Marche, the 51st ECB was closing down its sawmill operations and organizing for battle. At 17:30 on December 17, Anderson phoned with orders for one company to move on Trois-Ponts at once. Company C, commanded by Captain Sam C. Scheuber, drew this assignment.

An advance party of about 75 soldiers, led by Company C’s admin officer, 1st Lt. Joseph Milgram Jr., got on the road by 22:00. Their squad trucks filled with explosives, ammunition, and rations, the engineers traveled a familiar route from Marche to Trois-Ponts. Their journey should have taken 45 minutes, but as Milgram remembered, an unexpected traffic snarl created long delays.

“Although it was pitch black, our eyes had grown somewhat used to seeing and it seemed to us that every conceivable kind of vehicle including tanks, tank destroyers, artillery pieces in tow, command cars, jeeps, and trucks was coming the other way, bumper to bumper, sliding off the road and having all sorts of trouble moving. And here we were idiots heading east.”

Milgram and his detachment arrived around 23:30, while Company C’s remaining 65 G.I.s (21 men were left behind to guard equipment) closed on Trois-Ponts during the early morning hours of Monday, December 18. They got to work immediately, setting up machine-gun positions and wiring the two bridges in town for demolition.

As Company C lacked sufficient manpower and explosives to cover all three spans, Colonel Anderson called on the 291st ECB for additional troops to rig the Salm River trestle south of town for demolition. Lieutenant Albert W. Walters’ platoon arrived after dawn to complete this task. Leaving a squad at the bridge to blow it in case enemy forces approached, Walters and the rest of his unit then joined Captain Scheuber’s defenses inside Trois-Ponts.

Another welcome addition to the U.S. garrison arrived early on December 18 when a halftrack and 57mm gun combination from Antitank Platoon, Company B, 526th Armored Infantry Battalion, suffered a mechanical breakdown while passing through Trois-Ponts. After its crew got their vehicle repaired, the cannon was positioned east of town along the Stavelot road. Two infantrymen, Privates Francis R. Frazier and Ralph J. Bieker, next went out about 250 yards to provide early warning. Frazier and Bieker carried with them a “daisy-chain” of linked antitank mines they were to draw across the road right in front of the lead panzer.

Back at the ambush site, engineers S/Sgt. Fred Salatino and T/5 Jacob Young manned a truck-mounted .50 caliber machine gun to provide covering fire. Their platoon leader, Lt. Richard Green, posted himself in a ditch behind the 57mm cannon. In overall command was the 1111th ECG’s Capt. Robert Jewett, who monitored events from a halftrack parked nearby.

On a rise 1,200 yards south of Jewett’s position, Lieutenant Fred Nabors’ engineer platoon set up a blocking position designed to close the back door against any assault on Trois-Ponts. Nabors had just two Bazookas in his antitank arsenal but convinced himself that poor roads on the hilltop he was holding ought to deter armored vehicles from attacking there.

With all highway bridges loaded for demolition, fighting positions dug, and a rearguard keeping watch on the western approaches, Colonel Anderson decided to relocate the 1111th ECG’s command post. At 10:00, with the sound of gunfire in Stavelot clearly audible to all, his staff began evacuating the Hôtel Crismer. Anderson remained behind to direct the desperate battle he knew was about to take place.

Four miles to the east, Peiper had enjoyed a bit of good luck when earlier that morning attacking SS PzKpfw. V Panther medium tanks found the Stavelot bridge undamaged. By 10:00, his tanks were over the Amblève and headed toward Trois-Ponts. Another flanking column of PzKpfw. IV medium tanks split off to ascend the high ground where Lt. Nabors’ engineers lay in wait.

First to see the fearsome Panthers clattering down from Stavelot were Frazier and Bieker, who dragged their daisy-chain of antitank mines across the road before dashing to safety. SS Senior Sgt. Oscha Strelow, commanding the lead panzer, calmly dismounted and removed the explosives before continuing on his way. It was now 11:15.

The first three tanks in line rounded a bend and spied the Americans’ 57mm, opening up on it with their powerful 75mm cannon. Shooting back, the gun crew temporarily immobilized Strelow’s Panther with a lucky hit. They managed to get off a few more rounds before German high-explosive shells destroyed the piece, killing the crew.

Back in town, Anderson heard tank guns firing 500 yards to his front and knew exactly what it meant. There was only one thing to do; at 11:45 he ordered the Amblève River bridge blown. The roar of exploding TNT told all within earshot that armored vehicles using the Stavelot road could no longer enter Trois-Ponts.

The noise of the Amblève bridge going up behind him prompted Captain Jewett to order a hasty retreat. Boarding their squad truck and halftrack, those surviving members of the Stavelot road ambush force drove north along a country lane to La Gleize, then over the river at Cheneux. Green’s platoon returned to Trois-Ponts via a roundabout route at 15:00.

Peiper, expecting the Amblève crossing might be denied him, detoured his advance guard up the same route taken by Jewett and Green. From an observation post across the river, Anderson counted 19 German tanks heading north and dispatched several couriers to warn First Army HQ of this alarming development. Anderson also witnessed a war crime when he saw an SS tank commander execute two elderly Belgians who had unwisely emerged from their house.

A total of 19 civilians from Trois-Ponts are known to have been murdered by Peiper’s men. Their names have been listed on a plaque now affixed to the rebuilt Amblève River bridge.

As Kampfgruppe Peiper’s main body advanced northward along the Amblève, a new threat emerged on high ground south of town. Three PzKpfw. IV tanks, vanguard of that armored element sent to outflank Trois-Ponts’ defenders, entered the battlefield around 12:00. Encountering a string of landmines blocking their path, these panzers halted directly inside Lt. Nabors’ kill-zone.

His first Bazooka team missed its target, unfortunately, while Nabors’ second rocket launcher malfunctioned. The now-alerted tanks began firing back, destroying his platoon’s one working Bazooka and disabling their daisy chain. Unable to hold, the engineers withdrew off their hilltop ambush site and moved down to rejoin Company C’s position across the Salm.

They were not followed, as Peiper had ordered his southern attack force back due to low fuel. The Americans, however, could not know this. Seeing enemy panzers on the hillside opposite Trois-Ponts, Anderson reasoned his adversary’s next objective was the Salm River highway bridge in town. To deny the Germans that critical structure, he had it dropped at 13:00.

Conditions were deteriorating rapidly inside Trois-Ponts. That afternoon, machine-gun fire nearly decapitated Anderson as he conferred with a lieutenant outside his old headquarters building. Later, while observing from a ridgeline with Captain Scheuber, the stoic colonel attracted a German tank crew’s attention.

“There we stood,” related Scheuber in a postwar account, “when an 88mm tank shell went between us or slightly overhead to explode on the hillside beyond…. When we finished tumbling off that ridge (there wasn’t time to run) Col. Anderson and I ended up in about the same pile!”

Anderson had done all he could do to keep Trois-Ponts from falling into enemy hands. Peiper was still running rampant, though, and the 1111th ECG needed its commander present to help contain this dangerous foe. Yet the situation here required an experienced officer in charge, someone who would motivate and inspire the village’s defenders to keep fighting even though they were outnumbered, outgunned, and completely isolated from all friendly troops.

He found that strong leader at 13:30 when Bull Yates of the 51st ECB pulled into Trois-Ponts for what was supposed to be a routine staff conference. Scheuber showed Yates around Company C’s 500-yard outpost line and, before taking his leave, Anderson updated him on the situation. Yates also met with Albert Walters, the 291st ECB lieutenant whose engineer squad stood ready to blow the remaining Salm River bridge.

This detachment, led by Sergeant Jean Miller, sat tight until midafternoon when some German engineers (Pioniere) were seen approaching. Grimly, Miller waited for those men to step onto the bridge before he sent it skyward in a flash of blue light. Boarding their squad truck, Miller’s detail then escaped into the gathering dusk.

Meanwhile, in Trois-Ponts an enemy tank that had taken a wrong turn stopped straight across the river from Sergeant Evers Gossard’s position. When its crew dismounted, he opened fire on them with a .50-caliber machine gun. Five of six SS tankers fell, but one crewman climbed back inside and started to traverse the panzer’s main gun toward Gossard’s gun pit. He and his engineers “discreetly retired” until that vehicle eventually drove off.

As night fell, the immediate crisis confronting Trois-Ponts’ little garrison appeared to have passed. Peiper was now miles to the north, which meant those G.I.s holding the town no longer had to worry about a direct armored assault. Yet they were still vulnerable to occasional artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire, so Yates instructed his engineers to tighten their perimeter and stay alert.

“We kept sniping at them across the river,” he recalled, “but every shot of ours seemed to draw about a thousand in return. So we decided to deceive them as to how great a force we had available.”

He devised several ruses intended to convince any nearby German observers that the U.S. presence in Trois-Ponts was strong and growing. First, Yates assembled all six of his 2.5-ton trucks and repeatedly sent them speeding up and down a hill with their headlights on to suggest reinforcements arriving. He also had tire chains put on Company C’s 4-ton truck, instructing its operator to drive slowly around the village so as to simulate tanks moving in.

A vehicle accident occurring the night before further contributed to Yates’ deception plan. Sometime before dawn on the 18th, an open-topped artillery piece (variously identified as either an M7 or M8 Howitzer Motor Carriage) slid off the main bridge in town and ended up on its side in the Salm. The crew used thermite grenades to scuttle their mount, which caused the ammunition carried on board to “cook off” at irregular intervals over the next 24 hours. This pyrotechnic display sounded like artillery being fired and may have impressed inquisitive German listening posts.

Shortly after daybreak on Tuesday, December 19, a small patrol of combat engineers crossed the Amblève and cautiously made their way up the Stavelot road. Covered by Yates and three others, Lt. Green and Tech. Sgt. Matthew R. Carlyle observed four soldiers dressed as G.I.s standing around the wreckage of that 57mm gun knocked out in yesterday’s ambush. An M8 armored car and a jeep sat parked farther up the road.

Yet when Carlyle hailed the group, they yelled, “Amerikans!” and opened fire on him. He and Green had undoubtedly run into Panzer Brigade 150, a unit of German troops wearing Allied uniforms and equipped with captured vehicles whose mission was to infiltrate the lines, spread confusion, and—if possible—seize the Meuse crossings. Green’s party returned from this unusual encounter without loss.

Later that day, Lieutenant Nabors’ platoon engaged some infantrymen seen moving around on the hilltop they had abandoned the day before. The enemy replied with a storm of small-arms and artillery fire, prompting Nabors’ engineers to conceal themselves better and frequently change positions in the face of what everyone in Trois-Ponts recognized was an expanding SS presence across the river.

At 20:00, help finally arrived in the form of three armored cars belonging to the 85th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron. Creeping in from the west, these vehicles took fire from Yates’ rear guard—likely out of fear they were part of Peiper’s group or Panzer Brigade 150. Once the recon troopers identified themselves, though, they were eagerly incorporated into Yates’ defenses.

Although the G.I.s holding Trois-Ponts could not know it, senior commanders on both sides had started moving men and armored vehicles toward this key crossroads village as a direct response to Kampfgruppe Peiper. That SS officer, stymied by another blown bridge at Habiemont, detoured north to Stoumont where his column ran out of fuel. The Germans dispatched a mechanized relief column to link up with Peiper’s battle group, resupply his panzers, and continue 1st SS Panzer Division’s drive on the Meuse.

Another powerful task force gathered 10 miles to the west in Werbomont. The elite 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), 82nd Airborne Division, had recently traveled 150 miles from its rest camp in France after being released from Allied theater reserve to join the fight. In its haste to deploy, however, the 505th was “going in blind”—that is, without any maps or tactical intelligence on what lay ahead.

Unaware of the situation in Trois-Ponts, Regimental CO Colonel William E. Ekman joined his 2nd Bn. (2/505) as that unit warily moved forward on the morning of Wednesday, December 20. Most of Ekman’s paratroopers were on foot, but the colonel personally led one truck-mounted platoon into town as an advance guard. He found it held by weary but resolute U.S. combat engineers under the command of Yates, who greeted him with an exuberant “I’ll bet you guys are glad we’re here!”

Things began to happen quickly. To provide early warning, one rifle company crossed the Salm and established an outpost along the same high ground previously held by Nabors’ platoon. The rest of 2/505 deployed on line, lengthening the engineers’ defensive perimeter by several hundred yards.

With assistance from Scheuber’s men, a platoon of airborne engineers partially rebuilt the bridges inside Trois-Ponts that were destroyed on December 18. Soon, jeeps towing 57mm anti tank guns started making their way up a winding cart path to the Airborne’s hilltop observation post.

Back in town, sporadic artillery fire took its toll on several 51st ECB engineers manning the line. Around 19:30, large-caliber shells struck a machine gun position occupied by Sgt. Joseph Gyure and Pvt. Carl Strawser. Gyure was seriously wounded and Strawser killed in the blast. Later that night, another barrage took the life of S/Sgt. William W. Rankin.

At 03:00 on Thursday, December 21, G.I.s manning 2/505’s forward listening post reported hearing movement to the east. About daylight, Bazooka teams ambushed two armored cars bearing the insignia of 1st SS Panzer Division. These vehicles belonged to Kampfgruppe Hansen, a powerful task force built around one battalion of armored infantry (panzergrenadiers) as well as some Jagdpanzer IV tank destroyers.

Seasoned veterans themselves, 2/505’s paratroopers had never before fought against the SS and were shocked by the aggressive tactics of their heavily-armed opponents. Despite timely support from the 476th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, by mid-afternoon it became evident the hilltop outpost was about to be overrun. Ekman ordered a retreat, with Yates’ soldiers providing suppressive fire.

Incredibly, Colonel Hansen’s panzergrenadiers followed their foe across the Salm, fighting American paratroopers and combat engineers in the streets of Trois-Ponts until well past dusk. At 15:00, when this vicious brawl was at its worst, Yates received a phone call from the 1111th ECG directing him to pull his command out immediately.

Later, Yates recalled informing Anderson that “it was impossible to disengage from the enemy” just then, “as Company C was covering the withdrawal of the 82nd Airborne Division.”

Once the last panzergrenadiers were chased out of Trois-Ponts, though, Yates notified 2/505’s commander that his engineers had been ordered to depart. Yet there was one last task to perform, as both river bridges in town needed to be blown—again. The Amblève River span went up easily enough, but accurate German harassing fire kept a detail led by Lt. Joseph Milgram from properly rigging the larger Salm trestle for demolition.

After sunset, Milgram and T/5 Paul H. Keck crawled out over the bridge to load several TNT-filled “necklace charges” against a stone abutment on the enemy side. Then, rolling a length of primacord out behind them, both men waded the icy river back to friendly lines where Milgram checked their work and lit a fuse igniter. The shot fired perfectly, sending timbers flying in every direction.

At 19:30, Company C’s exhausted G.I.s boarded their squad trucks and departed the village they had held for four eventful days. Yates also released Lt. Waters’ 291st ECB platoon, offering that officer a hearty “well done” for his soldiers’ stalwart work. The engineers’ mission in Trois-Ponts was finally accomplished.

Yates looked back with pride on his troops’ performance there. “I would find them asleep standing up after 94 hours on the job,” he said, “but they were standing up.” Indeed, the men under his command had done something truly remarkable. Against enormous odds, they stood their ground while all around them other U.S. forces were fleeing the battlefield.

Credit must also be given to Yates’ superb leadership. As one Army historian noted on the defense of Trois-Ponts: “[E]asy-going in nature but determined in spirit, Major Yates held together his little company by prodding, cajoling, and encouraging them to resist long after they had reached reasonable limits of human endurance.”

Perhaps the finest tribute to these G.I.s’ heroic stand came from the man they had thwarted. Speaking after the war, Peiper claimed, “If we had captured the bridge [sic] at Trois-Ponts intact and had enough fuel, it would have been a simple matter to drive through to the Meuse River early that day.”

A handful of steadfast soldiers led by courageous, inspirational officers helped turn the tide at Trois-Ponts. Already, Allied commanders had started planning a massive counterthrust that would first “flatten the Bulge” and then drive deep into Nazi Germany to end the war in Western Europe. Hard-working combat engineers were destined to play a vital role in this, the last offensive.

Author Patrick J. Chaisson writes from his home in Scotia, New York. The author wishes to thank Dr. Florian Waitl and Mr. Sam Robertson of the U.S. Army Engineer School Historian’s office, and Mr. Troy Morgan of the U.S. Army Engineer Museum, Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, for their invaluable assistance.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments