By Michael D. Hull

It could have been a futuristic nightmare straight from the science fiction tales of H.G. Wells, with terror weapons raining death and destruction on an unsuspecting London. But the date was Tuesday, June 13, 1944, a week after the Allied invasion of Normandy, and Londoners were being rudely introduced to Adolf Hitler’s newest armaments, sophisticated jet-propelled bombs known as V-1s, each capable of flattening several office buildings.

Hurtling daily across the English Channel from camouflaged ramps on the Belgian and French coasts, hundreds of the flying bombs plummeted without warning onto London and southeastern England. Office and apartment blocks collapsed, streets were cratered, and hundreds of people perished in department stores and cinemas.

Antiaircraft batteries blasted away at the fast-moving missiles, and nimble RAF Spitfire and Mosquito fighters gave pursuit and tried to nudge them off course by tipping their wings. But there was no effective defense.

Even more lethal V-2 rockets followed, and the British government would eventually acknowledge 5,000 deaths and 15,000 injuries inflicted by the new weapons. Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels exulted, “London is chaotic with panic and terror. The roads are choked with fleeing refugees.”

Even more lethal V-2 rockets followed, and the British government would eventually acknowledge 5,000 deaths and 15,000 injuries inflicted by the new weapons. Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels exulted, “London is chaotic with panic and terror. The roads are choked with fleeing refugees.”

Hitler had warned his enemies that he would retaliate with fearsome new weapons if the Reich was attacked, and he believed, even as his monstrous empire was starting to crumble around him, that he could turn the tide against the Allies.

Science and scientists played a much more significant role in World War II than in any previous conflict, as Tom Schachtman relates in Terrors and Marvels (HarperCollins, New York, 2002, 368 pp., 32 photographs, notes, index, $26.95 hardcover). Other books have dealt with the technology of the war, but none has endeavored to explore more fully the extent to which that technology was utilized.

While soldiers, sailors, and airmen battled on the various fronts, a major struggle was waged behind the scenes among engineers, physicists, chemists, mathematicians, and academicians—the “backroom boys” or “boffins,” as the British called them.

In a brisk, clear, and revealing narrative, Schachtman has done an impressive job of explaining the far-reaching scientific/technological aspect of World War II—from radar to proximity fuses, from depth charges to radio-jamming, from Enigma to sonar, from acoustic mines to atomic bombs.

The author points out that the attitudes of the war leaders toward science and technology had been formed during World War I. Winston Churchill, who had served as First Lord of the Admiralty early in the Great War, championed tanks and airplanes. He was innovative and always intrigued by gadgets, but was no student of science. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a former assistant secretary of the Navy, believed that he needed no scientific training for his job and was only marginally interested in science.

The World War II leader most directly and perhaps most deeply affected by science in the Great War was Hitler, says the author. His exposure to mustard gas scarred him psychologically and probably reinforced his belief in the near-magical power of science-based weapons of mass conquest.

Meanwhile, Schachtman writes, the armed forces, particularly those of Great Britain, America, and France, were slow to embrace technology. Decades after the debuts of cars, trucks, tanks, and motorcycles, many armies were having difficulty phasing out horse battalions. Captain Basil Liddell Hart, the famed British theorist, noted that well into the 1930s the manner in which the services reached decisions on the larger questions of strategy, tactics, and organization was “lamentably unscientific.”

When the war broke out, the Allies had a lot of catching up to do in a limited time. Because World War II was so predominantly a conflict of machines, this penetrating and intelligent study is highly relevant.

Auchinleck: The Lonely Soldier by Philip Warner, Cassell & Co., London, 2001, 288 pp., 38 photographs, 10 maps, chronology, appendices, index, $19.95 softcover.

Auchinleck: The Lonely Soldier by Philip Warner, Cassell & Co., London, 2001, 288 pp., 38 photographs, 10 maps, chronology, appendices, index, $19.95 softcover.

Operation Crusader, a confusing series of Western Desert battles from November 1941 to January 1942, saw the relief of Tobruk and the recapture of Benghazi by the British—and proved to both them and the Germans that Field Marshal Erwin Rommel could be beaten.

But it was at the Battle of First El Alamein from June 30 toJuly 27, 1942, that Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck halted the vaunted “Desert Fox” and robbed him of his last chance of reaching Cairo. With a bare numerical superiority of lightly armed, unreliable tanks and a critical lack of antitank guns, the British Eighth Army defeated the Afrika Korps and drove it out of Cyrenaica.

But neither Parliament nor the usually astute Prime Minister Winston Churchill grasped its significance. Although Churchill overcame a vote of no confidence in the House of Commons, he wanted a resounding, decisive victory in the desert, and he no longer believed “the Auk” capable of achieving it.

Auchinleck was winning in the desert, but Churchill could not sense it, and even Field Marshal Alanbrooke, the equally astute Chief of the Imperial General Staff, feared that his friend was losing his grip. Like Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander, the Auk was a gentleman who led by example and suggestion and was ill served by a number of high-ranking subordinates who had not mastered desert tactics. Unlike his successor at the helm of the Eighth Army, the able but insufferable Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery, Auchinleck was not ruthless enough to wield a hatchet. And the Auk’s stubborn refusal to accept Churchill’s prodding soured the leader’s confidence in him. Ultimatums led to eventual dismissal.

The enigmatic, controversial Auchinleck—the first British general to defeat the Germans in World War II—is reclaimed for posterity in this distinguished biography by Philip Warner, author of a number of outstanding works on WWI and WWII. It is a penetrating and intelligent examination of a widely underrated soldier—sympathetic yet well balanced.

Auchinleck, says the author, was a superbly professional “honest-to-God soldier.” His men loved him, and he had a better understanding of desert warfare than anyone else at the time. His grasp of a battle and his command of often ill-trained and poorly equipped troops were second to none, says Warner. His eye for ground, his strategic planning and administration, and his ability to drive men on by his presence and example remain largely unrivaled.

He was considered by many to be the best field commander of the war, and was, Warner believes, a better leader than Monty. But, for all his courage and skill, Auchinleck could be obstinate and overfatalistic, and his kindness to others led to the well-founded charge that he “could not pick his subordinates.” The austere, solitary veteran of the Indian Army and three-time commander-in-chief was no politician, and his failure to learn the art of manipulation brought him humiliation at a time of personal triumph.

As portrayed in Warner’s book, the Auk was an uncomplaining, self-sufficient man incapable of self-pity or malice. He had schooled himself to face his setbacks alone. While Monty never excused what he interpreted as failure in others, Auchinleck was prone to do so. Despite his rank and fame, he was a humble man. As the equally revered Field Marshal Sir William Slim of Burma fame said of him, “In all the time I served with him, I never heard him speak ill of anyone—and, by God, he had reason to. Nor would he believe evil of anyone, and this may have been a chink in his armor.”

Literate and insightful, this is a most worthy biography.

Recent and Recommended

The War with Japan: The Period of Balance by H.P. Willmott, Scholarly Resources Inc., Wilmington, Del., 2002, 174 pp., 8 maps, notes, $60.00 hardcover.

The War with Japan: The Period of Balance by H.P. Willmott, Scholarly Resources Inc., Wilmington, Del., 2002, 174 pp., 8 maps, notes, $60.00 hardcover.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the respected commander-in-chief of the Imperial Japanese Combined Fleet, told the saber-rattling militarists in Tokyo in 1940-1941 that if war with America came his forces would have a free rein in Southeast Asia for five or six months. But after that, as the sleeping giant stirred into vengeful action, there would be no guarantees. In fact, he was certain that Japan would lose a prolonged war with the United States.

Yamamoto’s prediction was accurate, and the period of Japanese success in Southeast Asia and the western Pacific had more or less run its course by May 1942. Occasional offensive victories would follow, but in real terms, Japanese conquests ended that month. The Battles of Coral Sea in May and Midway in June put pay to Japanese expansionism and forced the Imperial Navy and Army onto the defensive.

The Japanese High Command made a critical error in initiating a war with America, as Willmott explains in his study of the “period of balance” (May 1942 to October 1943) in the Pacific War, and it disregarded Carl von Clausewitz’s dictum: “The first, the grandest, the most decisive act of judgment which the statesman and general exercises is rightly to understand [the nature of] the war in which he engages, not to take it for something, or wish to make of it something, which it is not … and it is impossible for it to be.”

Therein lies the Japanese error, says Willmott, a distinguished British historian and the author of several scholarly books on World War II strategies and campaigns.

In this work he traces clearly and concisely the major actions in Southeast Asia as America—still reeling from the Pearl Harbor attack, humbled in the Philippines, and shifting her industrial and military might into gear—went onto the offensive against Japan. Providing a fresh perspective on familiar material, Willmott details the American plans, Coral Sea and Midway, the strategic choices available to Washington, and the grueling campaigns in eastern New Guinea and the lower Solomon Islands. His narrative is lean and informative, his reasoning sound, and his research impeccable.

If war is a political phenomenon, the author concludes, then it follows that its most important elements are political rather than military or material. But political elements cannot offset material or military deficiencies, or imbalances that are too severe.

This was the reality that Japan was facing by November 1943. It found that it had no answer to growing American might, and the reckoning was just a matter of time.

Dawn of D-Day by David Howarth, Stackpole Books (Greenhill Books), Mechanicsburg, Pa., 2001, 255 pp., 21 photographs, 3 maps, $19.95 softcover.

Dawn of D-Day by David Howarth, Stackpole Books (Greenhill Books), Mechanicsburg, Pa., 2001, 255 pp., 21 photographs, 3 maps, $19.95 softcover.

When British, American, and Canadian soldiers splashed ashore on five Normandy beaches on the gray, stormy morning of Tuesday, June 6, 1944, it was the long-awaited and defining moment of World War II.

As Prime Minister Winston Churchill observed, D-day was the largest and most complex amphibious invasion in history, and it heralded the certain defeat of Nazi Germany. Much hard fighting lay ahead, but the Allies had good reason that day to shout the news on front pages, to ring church bells that had been silent for four years, and to give thanks.

The horror and confusion, the high drama and triumph of that fateful day are recreated in this enthralling and comprehensive study by David Howarth, a respected British historian and author of acclaimed works on the Eastern Front, General Heinz Guderian, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, and the British Long-Range Desert Group.

The author interviewed British, American, French, and German participants—both military and civilian—and has woven an authentic, multihued tapestry of the D-day epic that is powerful in its simple humanity and eloquence. It stands beside Cornelius Ryan’s best-selling The Longest Day as a top-rank study of the Normandy invasion.

Howarth relates in hour-by-hour detail the air drops of the British 6th Airborne Division and the U.S. 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions, the landings by the U.S. 1st and 4th Infantry Divisions at Omaha and Utah Beaches, respectively, and the British-Canadian-French assaults on Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches.

No account of D-day has surpassed this book in its range of personal details, attention to the international aspects of the operation, and narrative artistry.

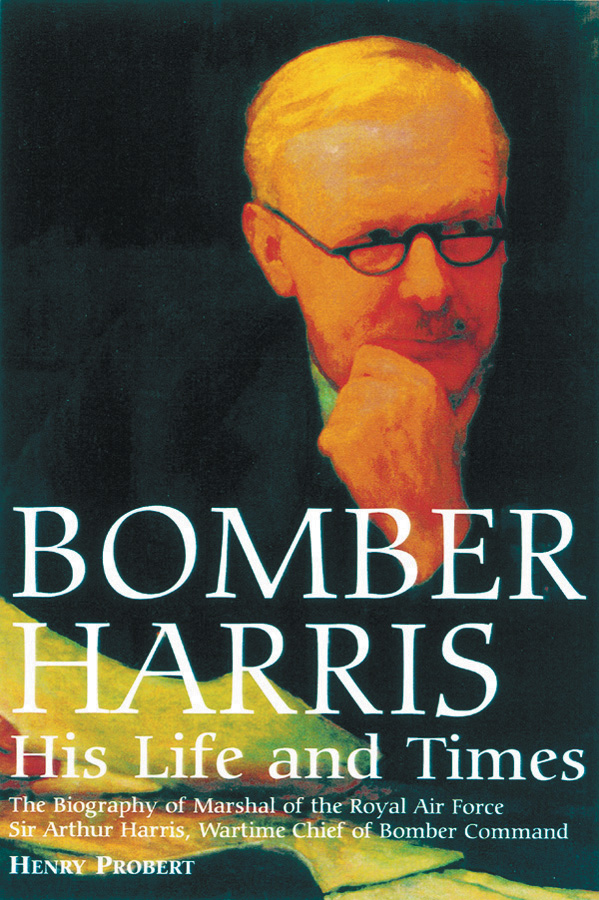

Bomber Harris by Henry Probert, Stackpole Books (Greenhill Books), Mechanicsburg, Pa., 2001, 432 pp., 62 photographs, 5 maps, 4 charts, appendix, index, $34.95 hardcover.

Bomber Harris by Henry Probert, Stackpole Books (Greenhill Books), Mechanicsburg, Pa., 2001, 432 pp., 62 photographs, 5 maps, 4 charts, appendix, index, $34.95 hardcover.

Between the London Blitz and D-day, as Prime Minister Winston Churchill often said, the “area bombing” of Germany was the only way in which Great Britain could hit back against Adolf Hitler’s war machine.

Wellingtons, Blenheims, Stirlings, Halifaxes, and Lancasters of RAF Bomber Command mounted regular raids that killed an estimated 600,000 Germans, many of whom were women and children, and flattened every large German city. The campaign did not win World War II, but it sapped enemy strength and morale and was wholly justifiable.

The early Bomber Command raids resulted in appalling losses and were sometimes ineffective, but the offensive ground on, directed with a firm hand from February 1942 to the war’s end by its architect, the intractable, single-minded Air Marshal (later Marshal of the Royal Air Force) Sir Arthur Harris. He vigorously defended his policy in the face of conscientious protesters in England and was convinced that Germany could be defeated by air power alone. He had no other interest, and his monomaniacal dedication would leave him one of the most controversial and maligned figures of the 1939-1945 conflict.

This definitive and long-overdue biography of the great air commander—who remains the target of vilification by critics long after his quiet death in 1984—was meticulously crafted by Air Commodore Henry Probert, a former RAF education chief and head of its Air Historical Branch. Although not distinguished by the most graceful prose, this is a critical yet sympathetic work of insight and honesty.

There is impressive detail here about Harris’s life and career: his schooling in England, his youth spent farming in Rhodesia, his gallant service on the Western Front in World War I and in India and Iraq, and his tireless leadership of the World War II aerial offensive. A complex man emerges, one who could be obstinate, ruthless, and rude. He did not suffer fools glady, and one of his standard greetings to senior civil servants was: “What are you doing to retard the war effort today?”

Yet he could also be generous, witty, and kindly. He went to great lengths to champion his air crews, and his graciousness in 1942 to his U.S. Army Air Forces colleagues—Generals Ira C. Eaker, Carl Spaatz, James Doolittle, and Frank Andrews—was a vital factor in paving the way for the massive Allied air campaign that hammered Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe by day and night.

This balanced, comprehensive study removes “Bomber” Harris from the rogues’ gallery to which many relegated him and pays him just tribute in the perspective of his stormy times.

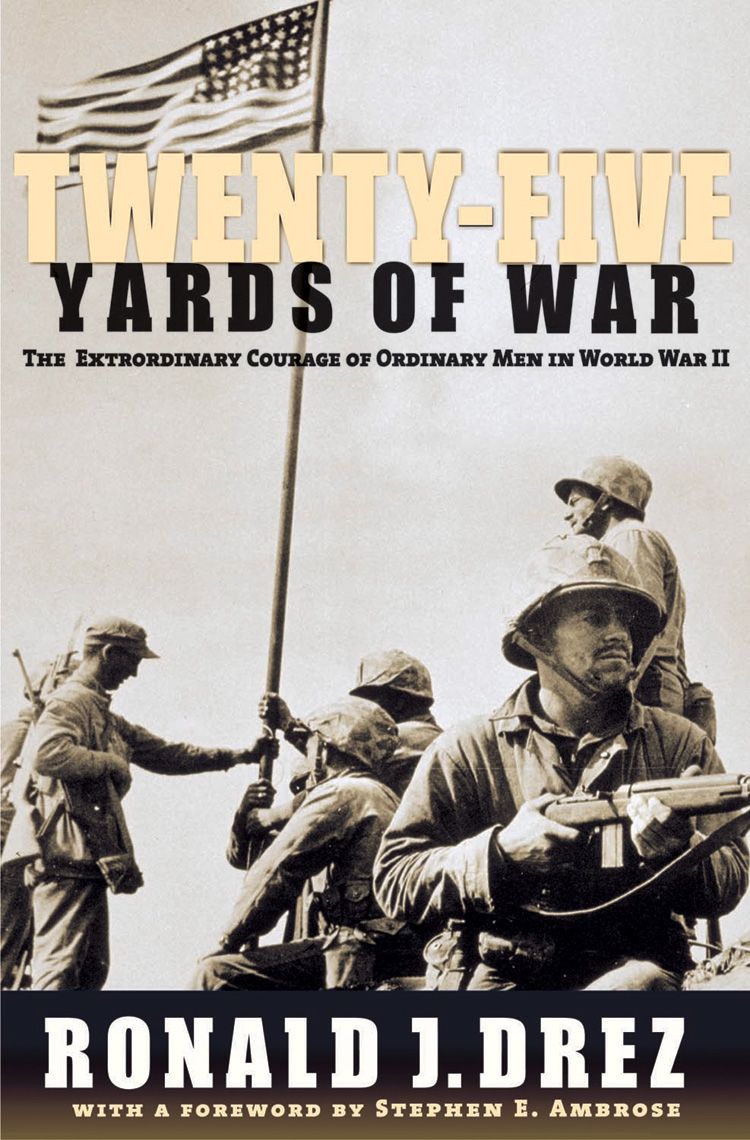

Twenty-Five Yards of War by Ronald J. Drez, Hyperion, New York, 2001, 320 pp., notes, index, $23.95 hardcover.

Twenty-Five Yards of War by Ronald J. Drez, Hyperion, New York, 2001, 320 pp., notes, index, $23.95 hardcover.

Napoleon Bonaparte said, “The first quality of a soldier is constancy in enduring hardship. Courage is only second!”

From Thermopylae to the Alamo, and from Rorke’s Drift to Wake Island, the lot of the combat soldier has changed little. The words may have changed, but not the meaning. How many front-line warriors, with constricted throats and hollow stares, have received the terse order, “Hold until relieved”?

It was rarely followed by an explanation, and nor was one needed. And it was the same situation on the battlefronts of World War II, where some cynics said, “We are the unwilling, led by the unqualified, to do the unnecessary, for the ungrateful.”

This book, a collection of firsthand accounts from a dozen American soldiers, sailors, and airmen in 1942-1945, delivers a powerful insight into the elite fraternity of men who have been to hell and back. It is intensely human and highly dramatic.

Author Drez, a Vietnam War combat veteran and research associate at the Eisenhower Center at the University of New Orleans, has done a masterful job of weaving the experiences of ordinary warriors—there are no generals or admirals here—into an eloquent and riveting narrative.

His subjects include Army Air Forces Sergeant Robert C. Bourgeois, who won the Distinguished Flying Cross for his part in the famous Doolittle Raid of April 18, 1942; Ensign George Gay, the only survivor of doomed Torpedo Squadron 8 at Midway on June 4-6, 1942; Private James Russell, who survived the 2nd Marine Division’s bloody assault on Tarawa on November 21, 1943; Private Kenneth Russell of the 82nd Airborne Division and First Sgt. Leonard Lomell of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, heroes of the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944; Navy Lieutenant (j.g.) Arthur Abramson, who won the Distinguish Flying Cross in the Battle of the Philippine Sea on June 19-20, 1944; First Lt. Lyle Bouck of the 99th Infantry Division, hero of Lanzerath, Belgium, in December 1944; Commander Eugene B. Fluckey, skipper of the hard-fighting submarine USS Barb in the Pacific and winner of four Navy Crosses; and Seaman Second Class Harold Eck, who survived the tragic sinking of the cruiser USS Indianapolis on July 30, 1945.

This is an inspiring and moving book. The foreword is by Stephen E. Ambrose.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments