By Christopher Miskimon

The messenger arrived as U.S. Navy Lt. James “Pug” Southerland tore into a sandwich and coffee in the wardroom of the carrier USS Saratoga. His division was ordered to take off and search for a flight of Japanese bombers reported as headed their way. He quickly strapped on his .45 automatic and went to his plane, a Grumman F4F Wildcat. They launched at 12:15 and by 1 p.m. flew at 12,000 feet over the transport ships offshore of Guadalcanal. It was August 7, 1942. Soon the air controller gave assignments; Southerland was sent on a heading of 310 degrees. Just after getting an update to turn left 10 degrees, he spotted the enemy bombers to his left, slightly above him about a quarter mile away. He made a quick contact report and ordered his division to switch on their machine guns and sight lamps. He said, “Let’s go get ’em, boys.”

The American fighter pilots attacked the 27 Japanese G4M “Betty” bombers just as they prepared to attack the transports below, their bomb bay doors already opened. Southerland picked a plane, made a low side run and fired, his four .50-caliber machine guns chattering. His burst caught the bomber, flown by Petty Officer First Class Shisuo Yamada, in its starboard engine, causing it to burst into flame. Fire and smoke trailing behind it, the doomed bomber turned nose down and crashed into the waters of the Sealark Sound below. Southerland banked left and down; as he did so Japanese bullets cracked his bulletproof windscreen and an incendiary round ignited a fire behind the cockpit. He thought another bomber’s tail gunner had scored the hits.

Despite the damage, the young lieutenant came around for another pass. “Thinking I might have to jump and not wanting to waste any ammunition, I returned to the attack,” he later said. Southerland made another low side pass on the right side of the enemy’s formation. He fired his remaining ammunition into another G4M, hitting its starboard engine and wing. That aircraft, flown by Petty Officer First Class Yoshiyuki Sakimoto, fell out of the formation, smoke flowing from its wing. The F4F was now smoking from its tail as well, but Southerland had just downed the first two Japanese planes of the Solomons Campaign.

The escorting Japanese Zero fighters now flew into the fight and its was Southerland’s turn under the guns of his opponents. Pairs of Zeroes took turns attacking him, and he soon developed a tactic to stay alive. The Japanese pilots would fly up on each rear quarter; as soon as he realized which one was going to fire, Southerland would turn sharply toward that plane, giving them a more difficult full deflection shot. Bullets peppered his rear fuselage but caused little damage. The Wildcat could absorb punishment, often surprising Japanese pilots. The armor behind his seat also took multiple hits, but none got through. Southerland could not know it, but Saburo Sakai, one of Japan’s top aces, was on his tail. Sakai later said he respected the courage of this Americna pilot more than any other during the war but made one last pass. His rounds struck and he saw the F4F burst into flame as he turned away. Southerland bailed out over Guadalcanal itself, down onto a part of the island held by the Japanese.

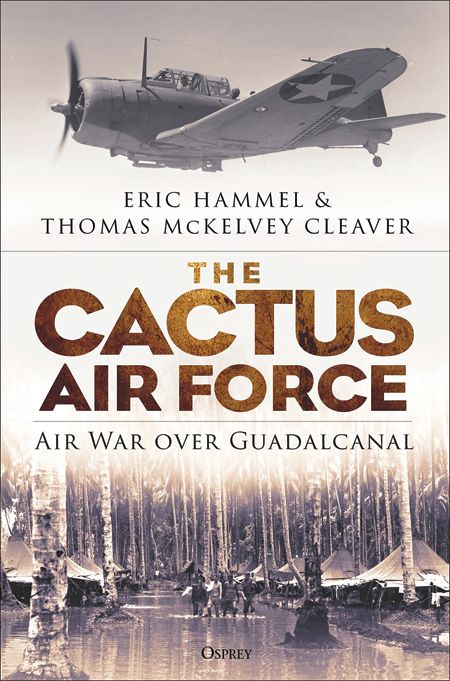

The air battles over Guadalcanal proved unrelenting for the pilots and aircrew. The island’s American code name, “Cactus,” gave its name to the group of aviators who fought from the island for months, doing their part to gradually attrit the Japanese forces in the Solomons, inflicting losses their enemy could not replace. Their story is told in The Cactus Air Force: Air War over Guadalcanal (Eric Hammel and John McKelvey Cleaver, Osprey Books, Oxford UK, 2022, 336 pp., maps, photographs, glossary index, $30.00, hardcover).

Both authors are known authorities on the Pacific War and this new book combines their writing skills and years of research into a single engaging volume. They cover not only the stories of the aviators who fought above the Solomons but also the leaders and planners who put them there, alongside the logisticians and others who kept them in the fight. The maps are clear and the images well-chosen. The narrative also does an excellent job relating air operations to the naval and ground actions of the overall campaign. Eric Hammel passed away in 2020, but his experienced hand in this work is clear and goes well with the equally skilled wiring of Mr. Cleaver.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments