By John E. Spindler

As the clock struck 8:00 p.m. in Arnhem, Holland, Lt. Col. John Frost’s British 2nd Parachute Battalion captured the north end of the road bridge over the Nederrijn River. Believing the enemy force defending the bridge consisted mainly of second-rate troops, Frost felt he would be able to overcome the Germans on the bridge and then hold until the rest of the British 1st Parachute Brigade arrived.

Amazed at the absence of security, Frost occupied the nearby buildings and attempted to secure the southern end, but Germans manning a pillbox repulsed the initial assault. After a brief reorganization, the paratroopers once more tried to take the entire bridge. Thwarted a second time, the British pulled back.

Two hours later, Frost dispatched a flamethrower team to eliminate the troublesome pillbox. Maneuvering into position with great stealth, the team successfully destroyed it.

Unfortunately, a handful of other buildings roared up in flames, including a maintenance hut being used as an ammunition depot. Flammable paint had caused the fire. The Germans had reopened the Arnhem Highway Bridge only recently after the damage it sustained during their invasion in 1940. The bridge caught fire after the ammunition exploded. The intense heat ruled out any more attacks that night.

Frost believed that rest of the 1st Brigade would arrive no later than the following morning in keeping with the plans of Maj. Gen. Robert Urquhart, the British 1st Airborne Division commander. The rest of the division would arrive later that day, followed the day after by Polish Maj. Gen. Stanislaw Sosabowski’s Polish 1st Parachute Brigade.

The British believed that by then the highway bridge and Arnhem would be in Allied hands, merely awaiting the arrival of the British XXX Corps driving up from the south. Once that happened, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s master plan for Operation Market Garden would be complete. Little did Frost know that things would not go as planned.

By early September 1944, the Allies possessed all of the offensive momentum on the Western Front. Numerous German divisions had been crippled in a disastrous battle at Falaise Pocket the previous month. The Allies had inflicted 50,000 casualties on the Germans and destroyed 500 of their tanks and self-propelled assault guns.

The British 11th Armored Division captured Antwerp on September 4; however, the Allies were unable to use its port facilities because of the Scheldt Estuary. Whichever side held the estuary controlled the sea lane to Antwerp. Despite the fall of Antwerp, the Germans remained in control of the mouth of the Scheldt. While the German defense in Holland consisted of the remnants of several German units that could be considered vulnerable to attack, the Allies could not launch a concerted offensive against the Germans units in Holland because their depots at French ports in northwestern France were too far away.

Montgomery believed that Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight Eisenhower’s broad-front strategy would result in the Allied advance eventually grinding to a halt at the German border. Eisenhower’s strategy called for the buildup of Allied forces along the Rhine River from the North Sea to Switzerland in preparation for a final offensive into the heart of Germany.

For his part, Montgomery advocated a single thrust that skirted the Siegfried Line to the north. The Siegfried Line, which the Germans called the Westwall, was a system of pillboxes and strongpoints built along Germany’s western frontier.

Pitching the concept to Eisenhower, the British field marshal envisioned a force of 40 divisions aimed at Berlin. Eisenhower declined the proposal because he did not want to halt the advance of Lt. Gen. George Patton’s Third Army. Recognizing the need to quickly capture the Channel ports, Eisenhower gave Montgomery’s 21st Army Group priority in receiving supplies. Montgomery also received the Allies’ last major reserve force, which was the First Allied Airborne Army.

Officially formed on August 1, 1944, the First Allied Airborne Army comprised the U.S. IX Troop Carrier Command, American XVIII Airborne Corps, British 1st Airborne Corps, and the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade. The British corps was made up of the 1st and 6th airborne divisions. Eisenhower tapped American Lt. Gen. Lewis Bereton to lead the new airborne army, with British Lt. Gen. Frederick Browning as deputy commander. The Allied planning staff received a good deal of pressure to devise an operation that would employ the First Allied Airborne Army.

While the Allied forces were outrunning their supply chain, the Germans had their own problems. Fragments of shattered divisions had hurried across Holland in a panicked retreat. The German military traffic over the Arnhem Bridge peaked on September 4. The town had not seen such a heavy volume of military traffic since the German invasion in May 1940. Field Marshal Walther Model, the commander of Army Group B, set up his headquarters in Oosterbeek, where he focused on shoring up the German defenses in Holland.

He also began devising a plan to extract General Gustav-Adolf von Zangen’s Fifteenth Army from the Scheldt Estuary islands. Written off by Allied intelligence, several of its units were ferried across at night. By September 10, Model had managed to stop the retreat. He then began establishing a defense composed of ad-hoc formations known as kampfgruppes.

Between D-Day and the first week of September 1944, the Allies had cancelled 14 airborne operations. In most instances, the advancing Allied divisions had already achieved the target of the airborne operation. Before receiving control of the First Allied Airborne Army, Montgomery had developed Operation Comet. This limited airborne plan, which was never realized in its original form, called for using Maj. Gen. Robert Elliot Urquhart’s British 1st Airborne Division and the Polish Brigade to capture several bridges in central Holland, including those from the Grave Bridge over the Maas River to the Arnhem Bridge over the Nederrijn. The plan called for the airborne troops to hold these critical crossings until General Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army arrived.

A number of commanders disliked the plan. Sosabowski spoke out at Urquhart’s planning meeting about the casual dismissal by the planners regarding the effectiveness of the German forces. Due to a period of poor weather and intelligence that noted a substantial increase in German strength in the vicinity of Arnhem and Nijmegen, Montgomery cancelled the operation on September 9.

The next day Montgomery met with Dempsey to discuss expanding Operation Comet to include more forces. Afterwards, Montgomery presented the expanded plan to Eisenhower. Under the codename of Market Garden, the 1st Airborne Division and the Polish Brigade would solely focus on Arnhem, and two American airborne divisions would secure other strategically important bridges. The Allies fused together two operations. The first, Operation Market, involved American and British airborne forces seizing nine bridges; while the second, Operation Garden, called for a powerful land force to swiftly follow over the captured bridges.

The British XXX Corps was selected to rush north across the captured bridges. Operation Market Garden was a departure from Montgomery’s normal operating method of a calculated, systemic assault. Instead, the British attack was to be an all-out dash in which the Allied forces involved would reach Arnhem in 48 to 72 hours. Eisenhower wanted to go as soon as possible, while Montgomery preferred to wait until September 24. The two commanders compromised and set the date for Sunday, September 17.

The 1st Airborne division, known as the Red Devils, was selected to capture Arnhem. Although many of its brigades were experienced, they had not fought together as a unit. Urquhart had never jumped before and experienced bouts of airsickness. The division comprised three brigades, each of which had three battalions.

Brig. Gen. Gerald Lathbury led the 1st Parachute Brigade and its battalions, the 1st Para Battalion, 2nd Para Battalion and 3rd Para Battalion. The 4th Parachute Brigade, under Brig. Gen. John Hackett, was made up of the 10th Para Battalion, 11th Para Battalion and 156th Para Battalion.

The third unit involved was the 1st Airlanding Brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Philip Hicks, consisting of the 1st Border Regiment, 2nd South Staffordshires, and the 7th King’s Own Scottish Borderers. Major Freddie Gough led the 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron, equipped with special jeeps. In total, 8,969 men would land west of Arnhem.

Urquhart and the Glider Regiment commander wanted a coup de main by which they would land five or six gliders as close as possible to the road bridge and seize it by surprise; a range of factors precluded it. The Allies had a transport-aircraft shortage. Needing to minimize their losses, U.S. IX Troop Carrier Command commanding officer, Maj. Gen. Paul Williams, wanted routes that avoided the Luftwaffe airbase at Deelen. He decided there would only be one lift per day, resulting in three lifts needed to get the forces into Arnhem.

“One of the greatest difficulties in mounting this operation rested on the inflexibility of Troop Carrier Command,” said a U.S. 82nd’s chief intelligence officer. As it turned out, Williams’ fears were for naught, as a Royal Air Force air raid on September 3 had left Deelen temporarily unusable.

Another factor was terrain. The urban area of Arnhem ruled out coup de main north of the Nederrijn. While the southern bank with its small, low-lying fields and many ditches looked attractive, it was actually unsuitable for gliders. It was known as polder ground and consisted of drained marshes that had been reclaimed from the river.

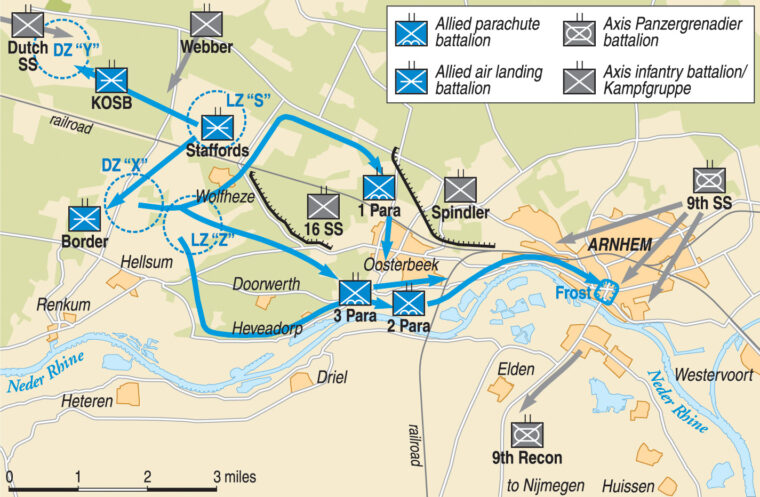

Urquhart was forced to select drop and landing zones that were up to eight miles from his objectives of Arnhem’s road, rail, and pontoon bridges. The 21st Independent Parachute Company would drop first to mark and secure the zones. He chose the 1st Parachute Brigade for D-Day, with most of Hick’s 1st Airlanding Brigade and the Reconnaissance Squadron. While the 1st Airlanding guarded the zones, the parachute battalions would advance on Arnhem by three different routes. Taking the southernmost route, which followed the Nederrijn, would be Frost’s 2nd Battalion. He was to secure the rail and pontoon bridges. Taking the middle and most direct route along the Utrecht Road would be the 3rd Battalion. Starting after the others and taking the northern route, the 1st Battalion would secure ground on Arnhem’s northern edge. Gough’s Reconnaissance Squadron was to use this route to race ahead and secure the bridge until the paratroopers arrived. The idea of using the local ferry was not discussed, which meant Frost never knew of its existence.

On D+1 the remainder of the 1st Airlanding and the 4th Parachute Brigade would arrive in the second lift. Going down another major street, the battalions of the 4th Brigade would push into the northern and eastern areas of Arnhem. On D+2 the Polish paratroopers would drop south of Arnhem while their glider-borne components landed near Wolfheze. Sosabowski’s men were to cross the highway bridge, secure it, and then relieve the 4th Brigade units in eastern Arnhem. By this time, or one more day at most, XXX Corps would arrive. On D+5, an air-portable division, the 52nd (Lowland), would fly into a captured Deelen Airfield.

The division’s fighting strength was further enhanced by the Glider Pilot Regiment. Unlike American glider pilots, the British pilots were trained to fight. The 1,262 men of the Glider Pilot Regiment furnished additional infantry until the arrival of XXX Corps. Two BBC broadcasters also flew into Arnhem.

Sosabowski’s Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade was organized along British lines. It possessed three battalions: the 1st Para Battalion, 2nd Para Battalion, and 3rd Para Battalion. In total, 1,684 Polish troops went to fight in the Arnhem area. The Allies did not consult Dutch military officials at any point during the planning for the massive operation.

The U.S. 101st Airborne Division would drop and secure the major bridges near Eindhoven. For its part, the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division would land south of Nijmegen. It would not only be tasked with taking key bridges, but also with securing Groesbeek Heights along the Holland-Germany border. Lower on the priority list was Nijmegen’s bridge over the Waal River. Browning and his headquarters intended to land 38 gliders in the 82nd Airborne’s zone.

Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks selected his Guards Armored Division to spearhead the 64-mile drive to Arnhem. Behind the armor was Maj. Gen. Ivo Thomas’ 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division, which was trained and equipped for making river crossings in the face of enemy resistance. The 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division completed the corps. The British VIII and XII corps would provide flank protection to the column.

Waffen SS General Wilhelm Bittrich’s II SS Panzer Corps, which comprised the 9th SS Hohenstaufen and the 10th SS Frundsberg panzer divisions, had retreated into Holland. Each division had approximately 3,000 men. The 10th SS Panzer was in much worse condition than the 9th SS Panzer. The divisions’ material strength was under 30 panzers. The 9th SS Panzer possessed most of the panzers, as well as some self-propelled assault guns, halftracks, and armored scout cars. Model had withdrawn the II SS Panzer Corps north of the Rhine for refitting after the Falaise Pocket ordeal. In orders that Model apparently had issued verbally, the panzer corps was sent to the Arnhem area. Model had randomly chosen that city.

Not only were these veteran panzer divisions, but the two divisions had spent months training in opposing airborne operations. As part of the rearming process, both divisions had been sent to Germany. For the training, the commander of Hohenstaufen division had received orders to turn over his heavy vehicles to the commander of the Frundsberg division. Lighter vehicles were loaded on railcars for the division’s transfer to Germany. The most important pieces of equipment purposely were scheduled to be the last to depart on September 17.

Allied intelligence on German forces was not reliable beyond 30 miles from the frontline. Many of the commanders participating in Market Garden believed that the opposition would consist of second-rate units. It was known that a pair of worn-out divisions had recently arrived in Arnhem, but Allied intelligence had lost track of the II SS Panzer Corps.

The planners continued to dismiss Sosabowski’s concerns about German strength in the target areas. The Polish general believed that the Germans knew how crucial Arnhem was as a gateway to their country and would staunchly defend it.

On the eve of the operation, Dutch Resistance reported that two SS-Panzer divisions had appeared in Arnhem. While the Americans gave credence to these reports, the British ignored them. The Germans had infiltrated the Dutch Resistance in 1943. Since that time, the British distrusted information given to them by the Dutch.

Browning’s intelligence officer, Major Brian Urquhart, who was no relation to the general, heard reports of increased German armor in the Arnhem region and persuaded his superiors for additional reconnaissance flights. Some of the photographs showed German armored fighting vehicles. The intelligence officers summarily disregarded the information, and the airborne assault proceeded as scheduled.

Other German units were in the area. One of these, located at Wolfheze, was the 16th SS Panzer-Grenadier Depot and Reserve Battalion, which was led by SS-Captain Sepp Krafft. Due to an increase in air raids in the area, Krafft had moved his men into the woods on September 16. He had little idea how fortuitous his decision would be when he awoke on the morning of September 17 to witness an Allied air strike under way to suppress German defenses in the operations area for Market Garden.

On the morning of September 17, 1,400 Allied aircraft bombed and strafed targets from the frontline to Deelen Airfield. Meanwhile, more than 1,500 transport aircraft and nearly 500 gliders in England prepared for history’s largest airborne operation. Earmarked for Arnhem were 475 troop transports and 320 gliders carrying the 1st Airborne Division’s first lift, protected by 371 RAF fighters. Since they were the slowest, the gliders departed at 9:45 a.m. The 21st Parachute Company pathfinders followed at 10:20 a.m. Ninety minutes after the gliders, the troop transports began their journey

At 12:40 p.m. the pathfinders jumped to mark drop and landing zones. Twenty minutes later, the lead gliders of the 1st Airlanding Brigade began their descent. By the time the landings had finished, and 283 of the 320 gliders had arrived. A few turned back, and some others had varying types of catastrophic accidents. For example, one eyewitness helplessly watched a glider split open and spill men into the English Channel. Other losses occurred upon landing when gliders struck trees or flipped over.

Having secured the immediate area plus Wolfheze, the 1st Airlanding Brigade noted the paratroopers dropping at 1:50 p.m. It took about two hours for the men to organize before heading to Arnhem. Contrary to the myth that most of the Reconnaissance Squadron jeeps were lost, only a few were destroyed or unsalvageable.

Correctly deducing the intended target, Krafft rallied his men. Even though the unit had just 435 men, it happened to be supplied with four experimental mortar-throwing launchers. He decided to block the two most direct paths, one being the railway and the other the Utrecht Road. His unit was ready in place before the British began their advance.

German officers on the scene quickly assessed the situation on their own without having to pass the information up the chain of command and await orders, as in the British Army. Model at first believed the paratroopers had dropped to grab him. He immediately took personal control of the type of battle that he excelled at, which was one of improvisation. Model received word from Berlin that his forces in Holland would receive top priority for reinforcements. Model also was informed that he could use the 68-ton Tiger II tanks of the 506th Heavy Tank Battalion. Armored personnel miraculously unloaded and made the tanks battle-ready in just five hours.

A 10th SS Panzer Division kampfgruppe was to head south and secure Nijmegen. In Arnhem, SS-Colonel Ludwig Spindler, the commander of the 9th SS Panzer Artillery Regiment, was ordered to set up a sperrlinie, or blocking line, with his artillery regiment and two grenadier regiments along the city’s western approaches. The Germans obtained a copy of the operation’s plans, including the drop schedule. But Model believed it was an obvious ploy of deceit.

Once ready, the 1st Para Brigade advanced towards Arnhem. After one and a half miles, the Reconnaissance Squadron ran into Krafft’s defenses. The Germans stopped the squadron cold. The same occurred to the 3rd Battalion. Taking the northern route, 1st Battalion initially advanced smoothly; however, it suddenly ran into Sperrlinie Spindler and could progress no further. Krafft withdrew his men to Kampfgruppe Spindler after midnight.

The Red Devils discovered that their Type 22 radios worked only intermittently; then communications failed altogether. The wooded landscape compromised its short range. Unable to talk with his battalions, Urquhart went out looking for Lathbury. After locating him, he intended to check on the operation’s progress. In the confusion of battle, Urquhart found himself caught behind enemy lines and ended up being trapped in an attic for almost two days. During that time, he was out of touch with the division when critical decisions needed his direction.

Along the river, Frost’s battalion found jubilant Arnhem residents more of a hindrance than the Germans. His C Company headed to capture the rail bridge, only to have it blown up in their faces. The Germans later captured the men of the company. Frost learned that the pontoon bridge was rendered useless by the removal of its center section.

SS-Captain Viktor Graebner’s 9th SS-Reconnaissance Battalion sped to Nijmegen, but a lack of communication among the Germans left the entire bridge unguarded for about one hour. Frost secured the northern end of the bridge; however, he missed his opportunity to take both ends by just 30 minutes. Three attempts failed to capture the southern end. After midnight, Frost received reinforcements in the form of a company from the 3rd Battalion and Major Gough, who arrived with two jeeps. He had slightly more than 700 men and a battery of 6-pounder anti-tanks guns to hold the area. Although days of hard fighting would still take place, Kampfgruppe Spindler, along with Krafft, had unknowingly stopped their enemy’s best opportunity to capture the road bridge.

South of Arnhem, several factors adversely affected Montgomery’s grand plan. The Son Bridge was blown in the 101st Airborne’s sector, resulting in a lengthy delay until completion of a Bailey bridge. Due to its lower prioritization, the Nijmegen Bridge was not captured. The Guards Armored Division advanced just seven miles on its first day. This showed that the XXX Corps commanders did not appreciate the urgency required in order for Operation Market Garden to succeed.

The second day of the operation began with weather delaying the second lift’s departure. During the night, Sperrlinie Spindler grew in strength and blocked the entire approach to Arnhem. Frost was now isolated at the bridge. A lack of interagency cooperation meant no close-air support for the paratroopers in Arnhem. Urquhart was still missing, and his lack of foresight to only tell his chief of staff about the chain of command’s line of succession complicated matters. Hicks received orders to assume command.

Early in the morning, the 1st and 3rd Battalions tried to follow Frost’s route, only to find German defense by that time extended to the Nederrijn. After a few hours, the assault was called off. Hicks ordered another attempt to reach Frost. He sent the incomplete South Staffords into the fray. He also changed the orders of the 11th Battalion when it arrived. Instead of proceeding to north of Arnhem, it was sent into the city.

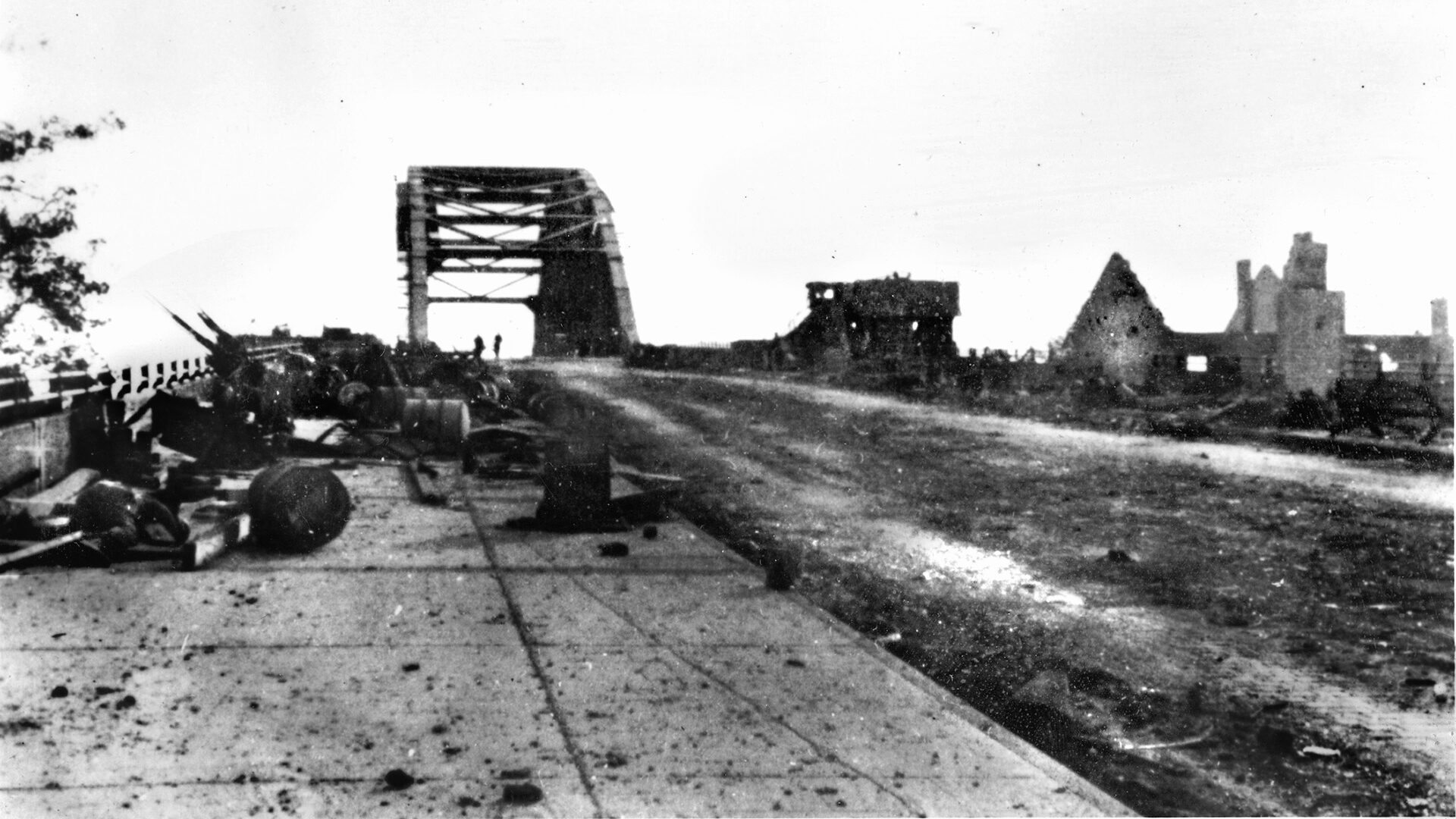

While the British attempted to break through to Frost, the 9th SS-Reconnaissance Battalion arrived back at the bridge. Graebner, who was awarded the Knight’s Cross on the previous day, decided to forcefully rush the bridge at 9:00 a.m. An hour later he and dozens of men were dead, with several of the battalion’s vehicles burning upon the bridge. Throughout the day, the 2nd Battalion sternly resisted all attempts to eliminate them.

At 3:00 p.m., the second lift arrived amidst flak. The 1st Airlanding Brigade did its best to maintain the security of the landing and drop zones, which kept casualties low. Hackett was upset when learning of Hicks’s alterations to the plan. The rest of the South Staffords and the 11th Battalion went to reinforce the attack, and in exchange, Hackett received the 7th King’s Own Scottish Borderers. The 10th and 156th Battalions headed to their pre-assigned positions northwest of Arnhem. Advance elements of the 156th met Sperrlinie Spindler, and the battalions opted to pull back.

Urquhart was still absent on Tuesday morning. Communication was virtually nonexistent, although the BBC correspondents, who possessed a different type of radio, made regular reports to London. The only news from Arnhem came from the media. Since the telephone system was still functioning, both the Germans and Dutch Resistance used it to communicate. The Dutch could not fathom why the British failed to take advantage of it.

A pre-dawn attack was scheduled with the South Staffords and 11th Battalion driving alongside the 1st and 3rd Battalions to pierce the sperrlinie along a narrow front between a railway and the river. The 156th and 10th battalions were to find a way through in the north. Due to a miscommunication, the assault began late. The 1st Battalion was noticed as it crossed open ground and took heavy fire. After incurring horrendous casualties, it was no longer a functioning unit. Witnessing this slaughter, the reduced 3rd Battalion provided cover fire, and the survivors pulled back.

A similar fate befell the 11th Battalion and South Staffords. Both were shredded when caught in the German’s crossfire. In the hours-long battle, all four battalions were cut down to a force of approximately 500 men. The only positive result occurred when Urquhart managed to escape and resume control. He called off the futile assault by the 10th and 156th battalions in the afternoon.

Weather in England continued to play havoc with the lift schedule. The troop transports carrying the Poles were cancelled, but their glider-borne portion departed. Upon arrival, the Poles found themselves in the midst of an intense battle for control of the landing zone. The contingent took casualties but would fight gallantly. No message had reached Britain about the supply drop zones being lost, so less than 10 percent of the supplies actually made it into British hands. Of all supply drops during the operation, less than 15 percent of the supplies reached British lines.

Frost’s men continued to hold out even though their casualties increased. The defenders defiantly refused a surrender offer. The Germans also were taking high losses. The German commander altered his tactics. He decided to blast out the defenders with high explosives and phosphorous rounds. The SS panzer veterans found the fighting unprecedented in ferocity. “This was a harder battle than any I had fought in Russia,” said SS-Squad Leader Alfred Ringsdorf.

With a Bailey Bridge erected over the Son, XXX Corps resumed its drive. The Germans tried to cut the route, which became known as Hell’s Highway. Though the attacks were unsuccessful, it drew off British armor that would have helped the advance. The flanking corps could not maintain pace over the rough terrain. This left XXX Corps and American paratroopers exposed to attacks by the German Fifteenth Army units that had been written off.

The following day, Urquhart made one of the toughest decisions of his military career—to abandon Frost’s battalion. Down to 3,600 men and with eight out of nine battalions mere shells of themselves, the Red Devils commander figured the best course of action was to consolidate into a thumb-shaped pocket centered in Oosterbeek with the Nederrijn at its base and await XXX Corps. He learned of the Heveadorp-Driel Ferry and made sure it was within the pocket.

Urquhart made contact during the day with Frost and told him the division was in no shape to rescue the 2nd Battalion. Both commanders believed XXX Corps would arrive that day. Urquhart contacted units outside of the Arnhem area, most likely by using the BBC correspondents’ radios, in order to get supply zones changed and shift the Polish drop zone to Driel.

Despite the ferocity of the battle, there were acts of chivalry when it came to collecting the wounded. The Germans, both Wehrmacht and SS troops, generally allowed British stretcher parties to operate freely. There was even an incident in which a 7th King’s Own Scottish Borderers officer temporarily commandeered a German panzer to transport wounded to an aid station. The Germans, though, treated the Dutch with great cruelty throughout the ordeal.

Gough had assumed command in Arnhem when Frost was wounded. With medical supplies practically nonexistent and medical facilities overflowing with casualties, a two-hour truce was arranged to transport 280 wounded men, one of whom was Frost, to German hospitals. That evening, the battle was practically over. The Germans crossed the bridge to set up defenses in Elst. The 82nd Airborne conduced a daring river crossing that helped capture the bridge over the Waal in Nijmegen. Sadly, Horrocks failed to have a fresh unit available to make the dash to Arnhem after the bridge’s seizure.

By 9:00 a.m. on September 21, the fighting near the bridge had ended. In the Oosterbeek pocket, reorganization of the defenses placed Hicks commanding the western and northern sides and Hackett the rest of the perimeter. The British were aided by a lack of coordination in the German attacks. The Guards Armored Division’s lead unit advanced up the narrow, elevated highway until stopped by a lone assault gun just six miles from the bridge. As XXX Corps neared, Urquhart had at last established good communications.

The communications enabled the 64th Medium Artillery Regiment to furnish critical and accurate support to the besieged. The British could not locate the Heveadorp ferry on the south bank of the Nederrijn. They believed it had been sunk, but actually it had drifted downstream after having its mooring lines severed.

The poor weather broke long enough for the Polish 1st Parachute Brigade to depart for Driel. An order from the IX Troop Carrier Command resulted in one-third of the transports, Sosabowski’s 1st Battalion, returning to England. Lacking the correct transmissions codes, the others pressed into Holland. The Poles arrived just after 5:00 p.m. under heavy fire. Setting up a defensive perimeter, Sosabowski sent men to locate the ferry, which he had been assured was in British hands. The Polish commander met with the Dutch Resistance and learned the ferry was gone.

Bittrich believed the Polish paratroopers were going to march directly to the bridge. The Germans diverted resources from their assault on the Oosterbeek pocket in order to reinforce the defenses at Elst. It is widely believed that this decision ended all hope for the 1st Division. Urquhart was keenly aware that the constant pressure from German mortar fire and sniper fire had thoroughly exhausted his men. He ordered a liaison officer to carry a message to Sosabowski. In order to get the message to the Polish commander, the liaison officer had to swim across the river.

The ground forces succeeded in contacting the airborne troops on September 22. While XXX Corps tried to batter their way through Elst, three armored cars from the 2nd Household Cavalry arrived at Driel by way of secondary roads. By that night, additional British infantry and tanks reinforced the Poles. Urquhart sent a message that the division could not hold out much longer. Sosabowski attempted to get support into Oosterbeek. Fifty-two men safely crossed the river using rubber dinghies that held two men.

The polder terrain that had limited the British armor also hindered the Germans, especially the 506th Heavy Tank Battalion’s King Tigers. The Germans found their steel monsters of limited use in Oosterbeek because the streets crumbled under their weight. Nonetheless, the tanks had the firepower to stop the British south of the river. The British ignored counsel from the Dutch about the need for infantry to accompany armor in the polder north of Nijmegen. The men trapped in the Oosterbeek pocket paid the price for the British arrogance.

In Oosterbeek, Urquhart had fewer than 3,000 able men to continue fighting given that the wounded overflowed existing medical facilities. More 43rd Division soldiers arrived in Driel, yet the Poles were ordered to try another crossing that night. Sosabowski became irritated, as it was the Wessex Division that was trained for river assaults, not his paratroopers. He learned that his 1st Battalion was making its way north after being dropped in the 82nd Airborne’s zone. He may have heard Hell’s Highway had been cut in the 101st Airborne’s zone. That night, 153 Polish 2nd Battalion paratroopers arrived in Oosterbeek before daylight made crossing too dangerous.

After just one hour of sleep, Horrocks visited Sosabowski. Learning of the situation in Oosterbeek, he invited the Polish general to a meeting that also included Browning and 43rd Division commander Thomas. Horrocks ordered Sosabowski to place himself under Thomas, who was a junior commander. Thomas informed Sosabowski that the newly arrived 1st Battalion was to cross the river that night along with his division’s 4th Dorsets in the same place as the previous attempts.

Sosabowski protested that a different location be chosen given that the Germans controlled the ground overlooking that crossing spot. For that reason, such an attempt would be suicidal. Browning used Sosabowski’s continual objections and stubbornness as a way to explain why the Arnhem operation had failed. British casualties continued to mount. During a two-hour arranged truce that afternoon, 450 British wounded were taken to German hospitals.

Browning discussed with Dempsey the evacuation of the 1st Airborne. Montgomery approved the idea. Urquhart received the order to plan for the withdrawal of the men. For that night’s crossing the 4th Dorsets’ commander was informed of the true nature of the mission, which was to be kept from his men. The mission was not expanding the bridgehead but strengthening the perimeter for its forthcoming extraction. The battalion was to be sacrificed to save the besieged men. Only enough boats arrived for the 4th Dorsets, and the disaster Sosabowski predicted became reality. Three hundred and fifteen soldiers of the 4th Dorsets survived the crossing, but most were carried downriver. The Germans captured 200 of them.

On the morning of Monday, September 25, the ninth day of an operation that should have been over in four days, Urquhart drew up plans for the withdrawal called Operation Berlin. Similar to the British evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula in World War I, the British would collapse the Oosterbeek pocket like a deflating balloon. The plan called for men to slowly make their way to the river starting with the northern perimeter, but still keep up the appearance of a fully manned defense. Those too severely wounded to walk would remain behind to await captivity. Medical staff volunteered to remain behind with them.

That night, the men blackened their faces and wrapped boots in cloth to muffle sound. The weather, which had been a curse to the British, became their ally as heavy rains fell that night, covering the withdrawal to the river bank. After a 45-minute artillery barrage, British and Canadian engineers crossed in two locations at 9:45 p.m. The Germans believed the crossings were just another reinforcement mission, never thinking the British were evacuating Arnhem.

The brave engineers continued to carry exhausted soldiers to safety even as the number of operational boats diminished. As dawn neared, some men opted to swim the Nederrijn. The British ceased Operation Berlin at 5:00 a.m., when the morning light enabled the Germans to deliver accurate fire. The British succeeded in evacuating 2,163 paratroopers and glider pilots, 160 Poles, and 75 Dorsets. The British left behind 400 men.

With the areas taken by the two American airborne divisions and the British Second Army, the Allies had a base from which to conduct further operations. For his part, Montgomery declared Operation Market Garden 90 percent successful. This success came at a high cost, as the 1st Airborne Division and Polish 1st Parachute Brigade would never recover from their losses. Even though 1,892 men of the 1st Airborne made it to safety, 5,903 were captured and 1,174 died.

The division returned to England in May 1945 and subsequently was sent to Norway. The Glider Pilot Regiment had 219 killed with a further 511 captured. Although the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade listed 92 dead and 111 captured, the 1,486 survivors would lose their beloved commander. Sosabowski, who was an outspoken critic of the operation, was made a scapegoat for its failure and forced to step down as the Polish brigade’s commander.

Exact German losses are not known. Model estimated his forces suffered 3,300 casualties, of which 1,300 were killed. Yet that figure includes the losses in the Eindhoven and Nijmegen sectors. Other estimates list at least 2,500 casualties at Arnhem.

The heroic sacrifices of the 1st Airborne were for naught. The British pulled back to just north of Nijmegen, as the salient was considered untenable. Martin B-26 Marauders of the U.S. Army Air Forces 344th Bomb Group destroyed the Arnhem Bridge on October 7. The Allies did not liberate Arnhem until April 1945.

Many revisionists believe the battle for Arnhem was lost by the delay in Nijmegen. Planning decisions, such as prioritizing the Groesbeek Heights over the Nijmegen Bridge, handicapped the operation before it began.

Williams’ decisions to limit the lifts to just one per day and his prohibition of a coup de main shackled Urquhart. The British chose distant drop and landing zones, thus forcing the Allies to lose the element of surprise necessary for such a daring operation to succeed. Add to this poor communications, adverse weather, and simple bad luck, and the odds seemed to have been stacked against the British and Polish paratroopers. Yet despite all these obstacles, the airborne men came close to succeeding. In the annals of history to this day, the Battle at Arnhem constitutes Great Britain’s last major battle loss.

monty’s mess

Worth reading “Arnhem a Tragedy of Errors” by Peter Harclerode for a more balanced opinion

Possibly true, but remember his plan was not executed as he wanted, no coup-de-mains due to Brereton’s decision that despite RAF wishes, they would not do more than one drop per day after laision with Paul Williams. Eisenhower, now Supreme Commander, could have called the operation off if he thought it too risky, but he didnt, he insisted on it going ahead. He had the power of veto.

Also, intelligence knew of the remnants of both SS Panzer Divisions at Arnhem, it was not arrogance. What they overlooked was the remaining strength of Germans and the ability to bring in tank supplies bia the Blitztransporte rail system.

The German 15th Army on the Schelt certainly played a part, but it was known by all, including Eisenhower, that to go ahead with MG the operation neccessary to clear theScheldt (requiring a major one) would need to be put on hold.

Finally, it was not 30 Corps fault that 82nd Division including Gavin and Browning, deprioristised taking the Nijmegen Bridge. 30 Corps arrived at Nijmegen at 11am on 19th September, 42 hours after setting off and just 9 miles from Arnhem. And it was actually the Grenadier Guards and 505th PIR who removed the main sections of Germans at Nijmegen before the British tanks took it. The heroic 504th PIR had taken the northern end of the railbridge but only arrived at the road bridge at 1915 hours according to divisional records, with the Germans in heavy retreat. The British tanks had already crossed at 1830 hours, again as per official American, British, and German records.