By Sam McGowan

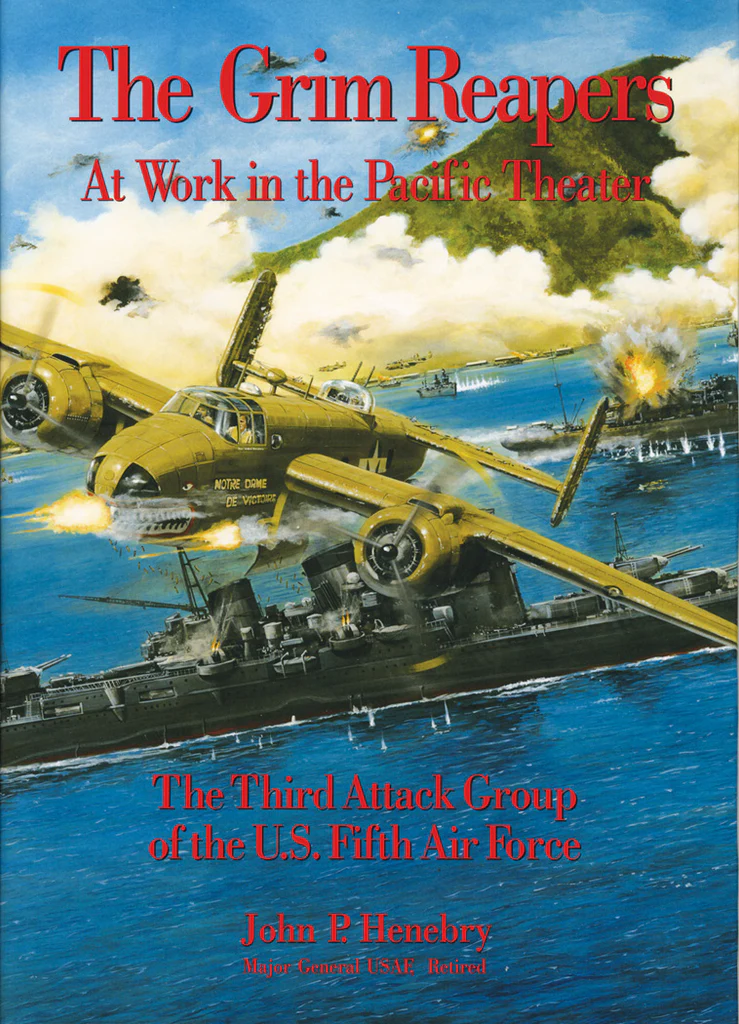

Once in a great while a truly historical figure takes the time to write a memorable account of that part of his life that put him in the history books. Retired Major General John P. “Jock” Henebry is one such person, and his account of his role in the Southwest Pacific Area of Operations in World War II deserves a place on the bookshelf of everyone seeking to learn about that great and terrible war.

In  : The Third Attack Group of the U.S. Fifth Air Force (Pictorial History Publishing Company, Missoula, Mont., 2003, 222 pp., 87 photos, maps, drawings, $24.95, hardcover), Henebry describes his dramatic experiences as a pilot and officer during World War II.

: The Third Attack Group of the U.S. Fifth Air Force (Pictorial History Publishing Company, Missoula, Mont., 2003, 222 pp., 87 photos, maps, drawings, $24.95, hardcover), Henebry describes his dramatic experiences as a pilot and officer during World War II.

After graduating from Notre Dame in 1940, Henebry entered the U.S. Army Air Corps as an aviation cadet. On December 7, 1941, Lieutenant Henebry was flying Boeing B-18 bombers on antisubmarine patrol. Six months later, after transitioning into North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers, he was on his way to Australia to join the soon-to-be-famous Third Attack Group and to earn his place in the history of World War II. The young officer would be one of the few American soldiers and airmen who were in continuous combat from almost the beginning of the war until VJ-day.

Henebry started flying combat as a lieutenant aircraft commander in mid-1942 and finished the war on the Far East Air Forces staff with his name on the list for promotion to brigadier general. During more than three years of combat, Henebry flew 218 combat missions, including some of the most important of the war. As a light and medium attack bomber pilot, his accomplishments rank with those of the fighter aces of the Pacific War—Bong, McGuire, Lynch, and Kearby. In the Fifth Air Force, Jock Henebry was as well known as any of the aces.

When Henebry arrived in Australia, the Fifth Air Force was struggling just to stay in the war. The B-25s in the Third Attack Group—a single squadron—were functioning as medium bombers, operating on level bombing missions against Japanese airfields, military installations, and shipping with limited success.

Then, Major Paul I. “Pappy” Gunn changed the lackluster B-25 into the most potent conventional aerial weapon of the war, and Jock Henebry became one of the pilots who would use it to its full potential. Under Gunn’s tutelage, the pilots of the Third Attack Group became masters of the art of low-altitude attack, and Henebry was one of the best.

The young pilot’s personal experiences read like a history of the Fifth Air Force, because he was a part of it from beginning to end and his role was a major one. During the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, he flew on the wing of Major Ed Larner, the commander of the 90th Bomb Squadron, as they led a 12-plane flight of B-25s in the strafing attack that U.S. Navy historian Samuel Eliot Morrison later described as “the most devastating” Allied air attack on ships during the war.

Six months later, Henebry himself led three groups of B-25s into Simpson Harbor at wave-top altitudes on the historic first full-scale raid against Japanese shipping at Rabaul on New Britain. As the commander of the Third Attack Group, it was Henebry who wrote the scathing report on the Douglas A-26 that pointed out that airplane’s limitations as a combat weapon. As a result, he was called to the United States to report to General Henry H. Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces, who considered the plane his personal baby. Arnold listened with disappointment to Henebry’s report, but ordered that his suggested design changes be incorporated into the production airplanes.

General Henebry tells his story with style and pulls no punches. One account describes the routine mission on which he was accompanied by a staff officer from General Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters, who put himself in for the Distinguished Service Cross. Henebry also relates how he was sent out with a flight of Douglas A-20s with orders to strafe and drop deadly parachute-fragmentation bombs on the villages of New Guinea natives. The orders had been issued in the belief that natives might assist the retreating Japanese. Henebry refused to carry them out.

The author recounts how a U.S. Army general on Leyte refused to allow his men to use his water. He describes the primitive life of the young airmen who were assigned to the forward airfields among the bugs, crocodiles, mosquitoes, and snakes of Papua, New Guinea, in a manner that puts the reader in the tents and mess halls. This book describes the Pacific War as it really was, not the way someone might imagine it to have been.

A Few Soldiers by William S. Clement, Xlibris Corporation, Philadelphia, 2003, 219 pp., photos, $31.99, hardcover.

A Few Soldiers by William S. Clement, Xlibris Corporation, Philadelphia, 2003, 219 pp., photos, $31.99, hardcover.

Since the 50th anniversary of World War II, there have been scores of memoirs written by veterans, but this is a book that stands head and shoulders above the rest, one that is easy to read and entertaining as well as informative.

William S. Clement was typical of the young men who awaited the call of his local draft board in the immediate wake of Pearl Harbor. After having been rejected as an officer applicant by the U.S. Navy, Clement soon heard the call and found himself on his way to Camp Forrest, Tenn., for U.S. Army basic training. Encouraged by his platoon sergeant to apply for Officer Candidate School, he went on to Fort Sill, Okla., for the Field Artillery OCS. He eventually ended up in England as a replacement officer with the 111th Field Artillery Battalion, a unit whose mission was to provide fire support for the 29th Infantry Division.

Composed primarily of National Guardsmen from Maryland and Virginia, the 29th Division would bear the brunt of the German resistance on blood-soaked Omaha Beach. Bill Clement was assigned as an artillery observer and became one of the men who flew in the low, slow-flying Piper L-4 Cub over the front lines. His pilot was his closest friend, and the little airplanes they flew continue to hold a fond place in their hearts. The two-man team went through several of them, starting with the loss of their original bird while it was still strapped to a truck on a landing craft 150 yards off Omaha Beach.

Clement’s story is about his military experiences, but even more important, it is about people. He has chosen a unique style of presenting his story in a series of short vignettes, describing in each his association with someone from his life, both civilian (before and after the war) and military during the war years. Clement’s writing style is very entertaining, and he relates his vignettes with humor, without the whitewash that is so often used to paint broad strokes over military experiences.

If the subject of a particular vignette is a scoundrel, he says so, and if the man (or woman) is saint-like, the author tells why he holds the person in such high regard. Some of his revelations are almost shocking, such as the action taken by the battalion executive officer upon learning that the commanding officer had been killed during the landings. The man jumped on a boat and headed back to England!

This book should be read by anyone with an interest in World War II and the men who fought in it. It is also suitable for the reader who has little interest in the military or World War II, but who simply enjoys an entertaining read.

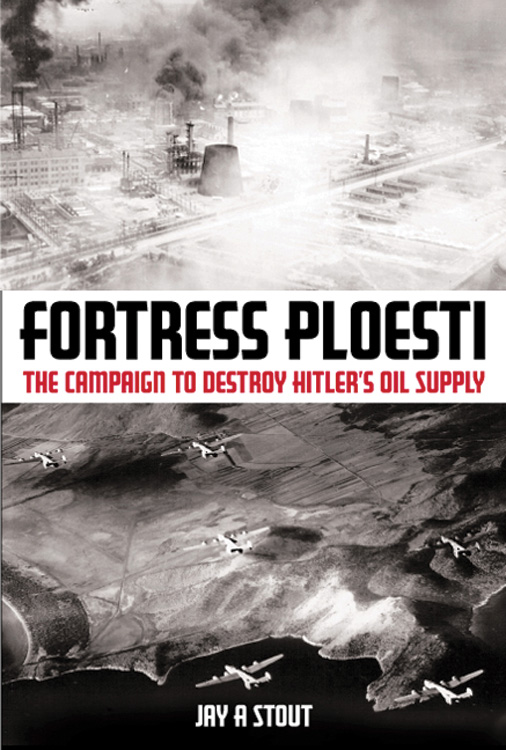

Fortress Ploesti: The Campaign to Destroy Hitler’s Oil by Jay A. Stout, Casemate, Havertown, Penn., 2003, 224 pp., photos, maps, $32.95, hardcover.

Fortress Ploesti: The Campaign to Destroy Hitler’s Oil by Jay A. Stout, Casemate, Havertown, Penn., 2003, 224 pp., photos, maps, $32.95, hardcover.

The oil refineries at Ploesti, Romania, were one of the most strategically important targets for aerial bombers during World War II, and the effort to destroy them makes an exciting story. Author Stout, a former U.S. Marine fighter pilot, tells the tale, commencing with the attacks by Soviet bombers early in the war and continuing through the June 1942 attack by American Boeing B-24 Liberators of the HALPRO mission, and on to the famous low-level mission of August 1, 1943. The narrative ends with the all-out bombing campaign against the refineries that began in the spring of 1944 and ended in the summer as Soviet forces approached Ploesti from the east.

Stout has done an outstanding job of chronicling the effort, particularly the 1944 campaign that finally put the refineries out of action. One chapter is devoted to a fighter-bomber attack by Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, a mission that was nearly as costly for the striking force as the low-level mission of the previous year.

There are some parts of the book that could have been left out, and there are some mistakes. The author devotes an entire chapter to the Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers that bore the brunt of the attacks on the Ploesti oil fields, with the focus on the bomber’s purported drawbacks. However, there is no similar chapter describing the characteristics of the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses that were also involved in the Ploesti campaign.

Stout makes the claim that the B-17 was the “superior” bomber, repeating a myth that is not born out by facts. Liberator groups did suffer significantly higher losses on missions to Ploesti than the Flying Fortresses, but the highest loss rate for a single mission—more than 18 percent on a day when 6.8 percent overall losses were taken—was suffered by the B-17s.

The author also extols the virtues of the North American P-51 Mustang over the Lockheed P-38s and Republic P-47 Thunderbolts, even though the famous P-51 was only beginning to enter combat in large numbers in the Mediterranean when Ploesti fell to the Russians and the air campaign ceased. He also states that the mission of August 1, 1943, code-named Tidal Wave, was so costly that it interrupted air operations by the Ninth Air Force. In fact, the same groups that went to Ploesti were over Weiner-Neustadt within two weeks and joined with Twelfth Air Force B-17s in a raid on Rome shortly after that.

Stout also misses the opportunity to compare the August 1, 1943, mission with the low-level missions flown in the Southwest Pacific by men such as Jock Henebry and the missions flown by RAF heavy bomber crews against other, equally dangerous targets. This reviewer has often wondered what the results would have been if a couple of groups of B-25 gunships had been sent after the refineries. After all, a small formation of A-20s destroyed a Japanese alcohol refinery on Formosa.

In spite of a few minor errors, Fortress Ploesti is a worthwhile book that contributes to the understanding of the air war. It is a must for those with a special interest in the attacks on Ploesti.

Never Alone by Harrison E. Lemont, Dorrance Publishing Company, Pittsburgh, Penn., 2003, 102 pp., $17.00, hardcover.

Never Alone by Harrison E. Lemont, Dorrance Publishing Company, Pittsburgh, Penn., 2003, 102 pp., $17.00, hardcover.

World War II was a war of steadily advancing technology, and the young men responsible for operating this new equipment often accompanied the combat troops into the field. Harrison Lemont was one such soldier. After basic training, he was assigned to the Air Corps and training as a forward air observer.

While Lemont was still in training, the Air Corps decided that forward radar stations were more important than visual observers, and the emphasis of Lemont’s training was changed to reflect that focus. Never Alone is Lemont’s story, from his induction into the Army to his discharge after the war at Fort Devens, Mass. He describes a bout of seasickness, an affliction that made his journey to Leyte Gulf a miserable one. Combat, however, was far worse.

Lemont’s company went ashore at Leyte while Japanese snipers were still picking off bulldozer drivers on the beachhead and set up a radio station next to a foul-smelling swamp. During a miserable existence on Leyte, he contracted jaundice. After Leyte, the company moved to Okinawa, then to a tiny coral atoll some 50 miles west of Okinawa where they were bombed and strafed by Allied pilots who were not aware that there were friendly troops on the 150- by 1,500-foot atoll.

Lemont emphasizes the family-like atmosphere among the men of his company, along with the dreadfulness of war, as illustrated by the constant presence of death on the Leyte beachhead. This is a tale of what war is really like, especially for those who are there to support the men who are engaged in combat on the front lines themselves.

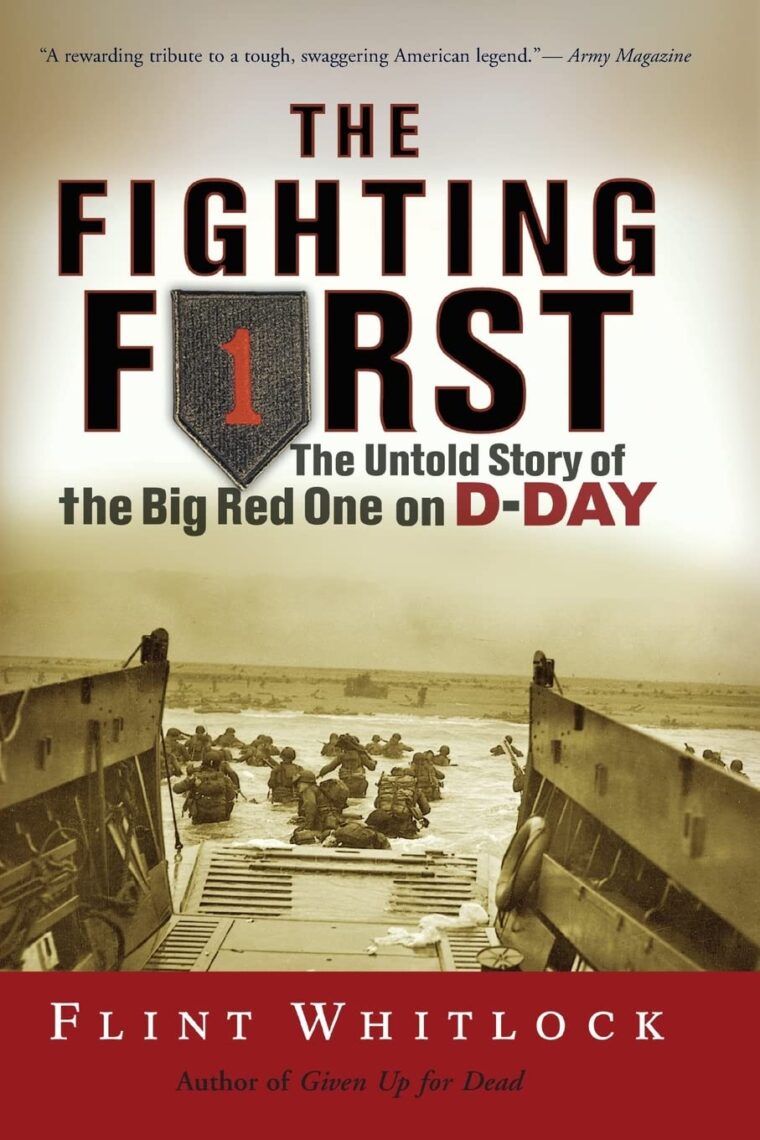

The Fighting First: The Untold Story of the Big Red One on D-Day by Flint Whitlock, Westview Press, Boulder, Colo., 2004, 384 pp., photos, maps $27.50, hardcover.

The Fighting First: The Untold Story of the Big Red One on D-Day by Flint Whitlock, Westview Press, Boulder, Colo., 2004, 384 pp., photos, maps $27.50, hardcover.

The subtitle of this new work by WWII History contributor Flint Whitlock reveals only a portion of the story contained within. The story includes the exploits of the men of the Big Red One, the 1st Infantry Division, from Normandy to the Elbe River just days before the surrender of Germany.

The first four chapters of the book detail events leading up to the D-day invasion, while the next three relate the experiences of the men of the division on June 6, 1944. The last three chapters cover the role of the division during the remainder of the Normandy Campaign and subsequent advance into Germany.

Whitlock’s well-written account combines oral histories, including numerous personal accounts from those 1st Division men who landed on Omaha Beach, with exhaustively researched material from period reports and archival resources. This is an excellent account of the role played by the men of the 1st Infantry Division in the liberation of Western Europe.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments