By Dr. Michael Rinella

The appointment of Erwin Rommel as commander of the 7th Panzer Division (nicknamed the “Ghost Division”) in February 1940 seems, in the light of his many triumphs in France and North Africa, an unremarkable and perfectly natural choice. At the time, however, nothing could have been further from the truth. For the invasion of France, code-named Fall Gelb (Plan Yellow), Germany had assembled roughly 135 divisions, but only 10 of these were panzer divisions.

Rommel had no prior experience commanding a division. Neither did he have any direct experience with the new blitzkrieg operations that had made their debut during the conquest of Poland in September and October 1939. He had not even commanded a combat unit during the invasion. The chief of Army personnel had recommended that Rommel be given command of a mountain division, based on his experience in the Alpine Corps during World War I. So why, in the early hours of the morning on May 10, 1940, was he leading a panzer division into the forests of the Belgian Ardennes?

Erwin Rommel’s Swift Rise Through the Ranks

What Rommel did have was regular, personal access to Adolf Hitler. Rommel and Hitler first met briefly in Goslar at a Reichsbaurentag, a traditional fair for farmers and landowners that the Nazis had elevated to a political event. It was at this meeting in Goslar that Rommel also met the Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels. He made a favorable impression and would henceforth enjoy his patronage.

Rommel was given a three-year appointment as instructor at the War Academy in Potsdam in October 1935, his teaching duties interrupted to perform security arrangements, such as at the summer 1936 Nuremburg rally, and acting as the War Ministry’s liaison officer to the Hitler Youth beginning in February 1937. He was picked to command Hitler’s escort battalion, the Führerbegleitbataillon (FBB), during the occupation of the Sudetenland in October 1938, and he repeated the task again twice in March 1939 during the occupation of the rest of Czechoslovakia and the Baltic port of Memel. In August he was the obvious choice to perform the same duties during the invasion of Poland. He was promoted to major general on August 22 (backdated to June 1). As headquarters commandant during the Polish campaign, he traveled on Hitler’s special train, named Amerika, and often shared the same car or light plane.

By 1940 the two had developed a liking for each other, sharing both humble origins and a deep dislike for the snobbery and elitism of the old German aristocracy. Rommel was neither a member of the Junker class of Prussian aristocrats nor a product of the General Staff (who denied him entry), both of which were essential prerequisites for military advancement prior to the rise of Hitler. Rommel desired command of a panzer division, and he received it, the objections of the Army personnel branch being overruled quite possibly by Hitler himself.

The appointment capped a truly rapid ascent through the ranks. Rommel had begun the month of November 1938 as a major who occasionally commanded an escort battalion. By February 1940 he was a major general in command of one of the 10 panzer divisions that would spearhead the campaign in the West. Hitler’s decision apparently raised more than a few eyebrows in the senior military hierarchy because, in a letter to his wife Lucie dated February 17, Rommel wrote, “Jodl [chief of the Operation Staff of the Armed Forces High Command, the OKW] was flabbergasted at my new posting.”

The 7th Panzer Division Was a “Propaganda Division”

From the start it was clear the 7th Panzer Division would be receiving high-level political attention and preference. Goebbels gave Rommel, an avid amateur photographer, a Leica camera to chronicle the campaign. Rommel intended to use the photos in the book he planned to write to follow up his popular Infantry Attacks. Manfred Rommel, his son, wrote, “… he planned to write on the Second World War … [my father] took literally thousands [of photos] … including a large number in color.”

Rommel himself mentioned, “I’ve taken a lot of photographs” in a letter to his wife written on May 27. A few of these photos that Rommel took during the campaign in France (or that were taken with the same camera while Rommel posed) are reproduced in The Rommel Papers. Most, unfortunately, were evidently lost in the in the aftermath of Germany’s defeat in 1945.

Attached to Rommel’s division as a second aide-de-camp was Lieutenant Karl August Hanke, a favorite of Goebbels who may have provided a special link to Berlin. The division’s officers included other Nazis such as Karl Holz, who had been editor-in-chief of the anti-Semitic weekly tabloid Der Stürmer [The Stormer or, more accurately, The Attacker]. In addition, one of Rommel’s former students at Wiener Neustadt, a Lieutenant Hausberg, was tasked with the duty of flying from the division to Hitler’s headquarters every evening to present a map showing Rommel’s progress that day.

The 7th Panzer Division was then, in a sense, no ordinary division but a showpiece of the Nazi government. While Rommel himself was not a member of the Nazi Party, he was no stranger to ambition and possessed a thirst for glory that, especially in the heat of a campaign, bordered on the unquenchable. At this early stage of the war he was not above exploiting the political connections he had built to advance his military career to the utmost.

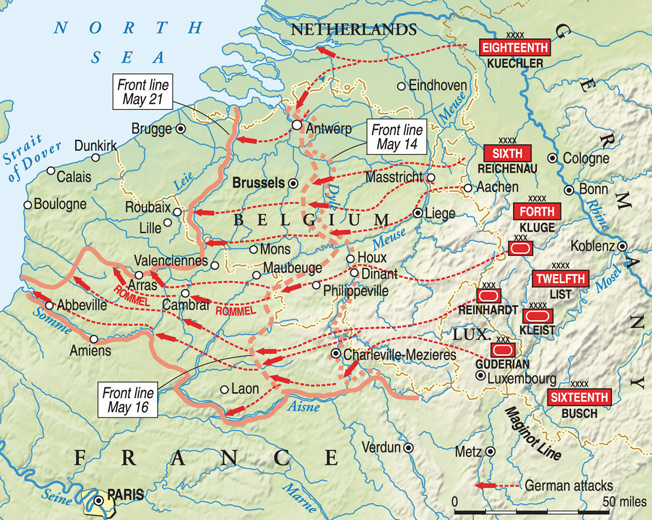

Army Groups A, B, and C

Rommel’s division, along with the 5th Panzer Division, would be the nucleus of XV Panzer Corps, which was part of the Fourth Army commanded by Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge. In addition to the XV Panzer Corps, Fourth Army had three infantry corps, the II, V, and VIII. The 5th and 7th were the only panzer divisions in the entire Army. Fourth Army itself, along with Twelfth Army and Sixteenth Army, was part of Army Group A, led by Field Marshal Fedor von Bock. It was the principal German strike force, the Schwerpunkt, for Fall Gelb.

Army Group B to the north would advance through Holland and Belgium in a feint to convince the Allies that the main German drive was in the north, while Army Group C to the south would demonstrate against the fortifications of the French Maginot Line. In contrast to Army Group A, Army Group B had but three panzer divisions, while Army Group C had none at all.

The Offensive Begins

The code word for the launch of Fall Gelb, “Danzig,” was received late in the day on May 9. Rommel wrote a last quick letter to his wife as he was packing; there would be no communication between them in the coming days. The 7th Panzer rolled forward at 4:35 the next morning, crossing the border between Germany and Belgium east of St. Vith. The 5th Panzer Division was on its right.

The initial objectives were the crossings on the Meuse River around Dinant, some 65 miles to the west. Overhead flew Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters from Luftflotte III. Initially resistance was light. The bulk of the Belgian Army was concentrated to the north on the plain of Belgium to defend the country’s major cities. The Belgians would be joined by some of the best French formations and the British Expeditionary Force, which advanced east to join them. Under this strategy, known as Plan D or the Dyle Plan, the Allies would defend a line from the French frontier to Antwerp.

The Belgian Army had conducted extensive demolitions in the Ardennes, but because few of the obstacles were covered by defensive fire German engineers had little difficulty clearing the obstructions. Where they could not be removed, the blockages were bypassed using side roads or, where possible, by moving cross country.

First Contact

Navigating the limited road network, 7th Panzer encountered its first serious Belgian opposition during the early hours of May 11, brushing aside elements of the 3rd Regiment of the Chasseurs Ardennais at Chabrehez. The role of the Chasseurs Ardennais was to fight a delaying action until the French could cover the flank toward their own border.

That task would belong to the French 9th Army, led by General André Corap. Corap, aged 62, had spent most of his career in French North Africa. He was, perhaps, as much an adherent to the old French school of military thought as Rommel was to the new lightning war employed by the Germans.

The French had sent their best armies into central and northern Belgium. The armies that had been detailed to cover the Ardennes, including Ninth Army, were much weaker. Corap’s army comprised two motorized and seven infantry divisions. Of the latter divisions only two were regular units, while two others were reserve divisions. To make matters worse, Ninth Army had been assigned a sector of the front 80 kilometers long, longer in reality because the Meuse River is not a straight line, but full of twists and turns.

The Ourthe River was crossed by the 7th Panzer Division at three locations—Beffe, Marcourt, and La Rouche. Soon thereafter, at Marche, French troops were encountered for the first time. These were elements of the 4th Armored Car Regiment of the 4th DLC (Division Lègére de Cavalrie). After just two days, 7th Panzer had advanced 40 miles. Another 18 miles would be covered on May 12. The 5th Panzer Division, however, had been slowed by the difficult terrain and thick forest of the Ardennes. Rommel alluded to this fact when he wrote to his wife that day that he was “way ahead of my neighbors.”

It would not be the last time Rommel’s division raced well ahead of the rest of the German Army. The French cavalry divisions, on Corap’s orders, methodically retired behind the Meuse River during the course of the day, with the Germans gradually following up. The cavalry was originally intended to delay the Germans for five days but Corap had felt it necessary to recall them after only two and a half when infantry support failed to materialize rapidly enough.

Crossing the Meuse

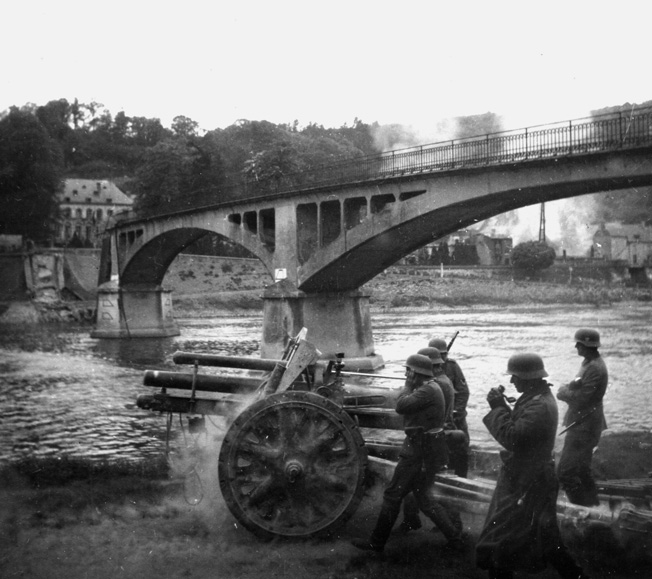

The need for Rommel to capture a bridge intact was critical. The Meuse was deep and wide, with steep and escarped banks. The French, however, were successful in blowing up the crucial bridges in front of the advancing XV Corps, including a railroad bridge at Houx, the road bridge at Dinant, and the road bridge at Bouvigne. In addition, the defenses had been bolstered by the transfer of the 2nd Battalion of the 39th Regiment, 5th Motorized Division, from General Bouffet’s II Corps to General Martin’s XI Corps. The new battalion took up a position on a hill opposite Houx, near the village of Grange.

Matters were not well in hand, however. The French had assumed they would have five days to reinforce and reorganize their defense if the Germans launched an attack out of the Ardennes, but Rommel was not about to allow them that sort of luxury. To make matters worse for the Allies, communications were poor, both among French units and between the French and Belgians. Allied morale on this part of the front was already showing signs of being unsteady. Rommel arrived at the Meuse in an armored car, examined the far bank with field glasses, and seeing it was well defended declared the job was one for infantry. His motorized infantry moved up and were “firmly in control of the east bank of the Meuse between Dinant and Houx” by the time the sun set on the 12th.

The German attack got under way in the early hours of the next morning. The western bank of the Meuse opposite the Germans was held by two French Infantry Divisions, the 18th and 22nd DI (Division d’Infantrie). Both divisions were still in the process of arriving after a lengthy foot march. Soldiers from Rommel’s 7th Motorized Infantry Regiment began to cross the Meuse at Dinant, and infantry from his 6th Regiment began to cross between Leffe and Houx. It was at Houx, in fact, rather than at Sedan, that German units first crossed the Meuse, at roughly 11:30 in the evening of May 12. A motorcycle battalion, leaving their bikes behind, crossed under cover of darkness, utilizing an old dam connecting a small island to both sides of the river bank.

There is some dispute over whether it was the motorcycle battalion of the 7th or 5th Panzer Division that crossed the Meuse at Houx, and the matter is further confused by the fact that the corps commander, General Hermann Hoth, had temporarily transferred control of elements of the 5th Panzer Division to Rommel, who was making faster progress. The dam and the lock had not been blown up by either the Belgians or the French for fear it would lower the river and actually make it fordable in some places. But it should never have been left as unguarded as it was. The Germans were lucky. The island at Houx lay right at the boundary of two French corps, the II Corps and the XI Corps, and for a single, fatal, moment no one was sure who was responsible for its defense.

The water crossing on the morning of the 13th was made largely in inflated rubber boats. Well-concealed French machine guns and artillery took a heavy toll. Observing that the crossing of the 6th Regiment was opposed by heavy fire and lacking a smoke unit, Rommel ordered houses in the Meuse valley set on fire “to supply the smoke we lacked.”

The attack at Houx was also fortunate in the sense that the 18th DI was still in the process of arriving and only a portion of it had reached the Meuse, and the units that were already in position were exhausted from a forced march of more than 50 miles. Even worse was the fact that, although German units had been over the Meuse since shortly before midnight the night before, General Martin was not informed until 7 am. He tried to contact General Corap, his army commander, but could not reach him by phone. Corap was not aware until the evening of the German bridgehead at Houx and the threat it posed.

Returning to the 7th Regiment, Rommel found that while it had formed a company-sized bridgehead on the opposite bank their crossing equipment had been destroyed by enemy fire, and things had come to a halt. Tanks and artillery, finally arriving, were used to silence the enemy fire up and down the point of crossing, allowing additional troops to cross and the wounded on the opposite bank to be retrieved. Rommel then personally took command of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Regiment, leading it across the river and linking up with the units already on the opposite bank. French tanks approached. They were unaware the German position lacked an antitank screen. Rommel ordered small-arms fire poured onto the enemy armor, and the ruse was sufficient to convince the French to withdraw.

“Onhaye Crisis”

By the morning of the 14th the advance guard of the 7th Motorized Infantry Regiment had reached Onhaye, two miles west of Dinant. Communicating by radio that he had “arrived” (eingetroffen), Colonel Georg von Bismarck was misunderstood as having announced he was “encircled” (eingeschlossen). Radio communication then failed, setting off a crisis that rippled all the way up the chain of command. Kluge, the army commander, spoke of an “Onhaye crisis” and diverted units in its direction. Rommel immediately organized all the tanks then available on the west bank of the Meuse to rush to von Bismarck’s aid.

The attack was led by Colonel Karl Rothenberg, commander of the 25th Panzer Regiment, with Rommel following close behind in one of the division’s few Panzer III tanks, so closely, in fact, that Rommel’s tank came under fire from French antitank and artillery guns, suffering two hits. Attempting to escape, the tank slid down a steep embankment where it became immobilized. Rommel bailed out with the crew and escaped with only an ugly gash on his chin. It had been a close call, and it would not be the last time Rommel’s life would be in danger during the campaign. An attack launched that evening reestablished contact with von Bismarck, ending the “crisis.”

French Tanks Meet Rommel’s Panzers

For the French Army, however, the crisis was only beginning. During the 13th and 14th all three German panzer corps had formed bridgeheads on the western side of the Meuse, though Reinhardt’s at Monthermé was precarious and encountering stiff resistance while Guderian’s at Sedan was only marginally better, having become the target of intense air bombardment. It was at this fateful moment on the 15th of May that Corap ordered a withdrawal of his Ninth Army westward to a new line. This had the effect of “uncorking the bottle,” allowing both Reinhardt’s and Guderian’s corps to pour out of their bridgeheads, through and around the slowly reacting French units and into open country. The French line now had a breach 60 miles wide, with nothing to plug the gap.

Opposite Hoth’s XV Corps, Corap’s new line included the railway that ran to the east of Philippeville, 15 miles west of where Rommel’s division had breached the Meuse. Before the new line could be occupied it was penetrated by the 25th Panzer Regiment. Rommel’s panzers, now with air support from the Luftwaffe, were striking deep into the rear of Ninth Army and forestalled an intended counterattack toward Dinant by the newly arriving French armored division, the 1st DCR (Division Cuirassee Rapide).

The 1st DCR had roughly 150 tanks to Rommel’s 218, but over half of these were the heavy B models that outclassed anything in the German inventory. The French medium tank, the Somua S35, was the best all-around tank on the battlefield in the spring of 1940, fast, well protected, and with heavier firepower than the Panzer III. A disadvantage of both the B models and the Somua was that a single individual had to load, aim, and fire the turret gun, while inside a German tank multiple crewmen could coordinate a heavier rate of fire. The 75mm gun on the B models was also hull mounted, which meant the gun could be redirected only by moving the entire vehicle.

Had the 1st DCR appeared on Rommel’s right flank unexpectedly it could have given him a nasty surprise. Instead, near Flavion, the Germans came upon the French just as their tanks were in the process of taking on fuel. Another disadvantage of the French heavy tanks was their rapid fuel consumption, which limited their operations to fewer than six hours before they had to refuel. Their fuel tankers, many of which were civilian models lacking tracks capable of operating on off-road terrain, had been delayed for hours.

A sharp engagement ensued at close range. The German panzers hit the heavier French tanks in their more vulnerable flanks. Their best bet was to shoot off the treads because the German guns lacked to the power to penetrate the French tanks’ thick frontal armor. Only about one-third of the tanks in the 1st DRC were operational at the end of the day. By the morning of the 16th, only 17 were still operational. During this same time period the 7th Panzer Division completed the destruction of another crack French unit, the 4th North African Division, which had been plugged into the line at Onhaye.

“The Most Spectacular German Exploit of the Day”

Reaching the French frontier just west of Sivry, Rommel now was faced with attacking the Maginot Line extension. The Germans did not make a distinction between the “true” Maginot Line, which ended at Longuyon, and its northern extension, which was made up only of a shallow belt of pillboxes and antitank obstacles, something that explains Rommel’s caution on reaching these less formidable fortifications.

There appears to have been some confusion on the morning of the 16th. Rommel received a message to remain at divisional headquarters for some unknown reason. It was not until 9:30 am that he was given permission to return to his advance headquarters. After moving forward and discussing the attack with his chief of operations, Major Otto Heidkaemper, Rommel was visited by Kluge, who expressed surprise that the attack was not yet under way. Rommel explained his plan, a careful set-piece assault, and it was readily approved.

The French defenses were successfully pierced as the sun set, and the panzers found themselves in open country by the early evening. At the head of the division, riding in Rothenburg’s command tank, Rommel now drove the vanguard of the 7th Panzer relentlessly. The advance continued, as planned, in the moonlight. The rout of the 1st DCR was completed at the town of Avesnes, with only three French tanks escaping. Unable to reach Hoth on the radio, Rommel refused to stop. On his own initiative he ordered the panzers to continue west, to Landrecies, wreaking havoc in the French rear.

Sunrise the following morning, the 17th, found Rommel’s forces eight miles west of Landrecies on a hill just east of the village of Le Chateau, exhausted and nearly out of fuel and ammunition. Two panzer battalions were now nearly 50 miles farther west than they had been the day before. The action was audacious to say the least. Rommel’s Avesnes raid had driven a long narrow “tongue” barely a mile wide into enemy territory. It was, according to author Alistair Horne, “the most spectacular German exploit of the day—possibly of the whole campaign—and one which, more than any other, was to establish Rommel’s reputation.”

Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross

The rest of the division was now far behind, dangerously so in the minds of some, including individuals on the divisional staff such as Heid- kaemper. He later wrote a memorandum, submitted to both Rommel and Hoth, complaining that a divisional commander ought to remain to the rear, at or close to his headquarters. Rommel was still learning the fine points of commanding a panzer division on the move and when the situation became a bit frayed he would improvise solutions. This sort of improvisation, Rommel noted derisively, was mistaken by a frightened “General Staff major” as a sign “the command of the division [was] no longer secure.”

But in this case at least Rommel had judged correctly. The effects of his aggressive night advance on an already shaken French Ninth Army had been decisive. The French units became more disorganized and more demoralized the deeper Rommel drove into their lines. Now Martin’s XI Corps and Bouffett’s II Corps had been all but destroyed. Corap’s army had virtually ceased to exist. Of the 70,000 troops it began the campaign with, only 7,000 remained. For his actions during these days after crossing the Meuse, Rommel was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. Rommel mentions Hanke presenting him the decoration on May 26 “on behalf of the Führer” and relaying Hitler’s regards, rather unusual duties for a junior officer. Rommel later returned the favor, recommending Hanke for the Iron Cross.

Rommel’s Bluff at Cambrai

The 17th was spent consolidating his rather precarious position. Rommel left the panzer battalions at Le Câteau in a defensive hedgehog and hastened back toward Avesnes with a single tank providing escort. The tank broke down, leaving Rommel in the midst of many French troops, still bewildered and shocked by recent events. He was lucky to escape capture. Eventually some 10,000 prisoners would be rounded up. The rest of the division, to Rommel’s probable frustration, was only just arriving in Avesnes. He personally led the remaining panzer battalion and the 37th Armored Reconnaissance battalion westward to link up with Rothenburg’s hedgehog, but not before fighting a sharp engagement with French tanks of a light mechanized division, the 1st DLM (Division Légère Méchanique), that had taken up blocking positions between Landrecies and Le Câteau.

Finally reaching Rothenburg, who had been fending off attacks by French tanks himself, Rommel was surprised to learn that for some unknown reason a supply column had not made it through with him. There was no choice but to dispatch units back to Avesnes again to ensure the supply columns could get through. Rommel recorded that the situation was not cleared up until 3 pm.

After this pause Rommel received orders from Hoth shortly after midnight on May 18 to push on to Cambrai, some 15 miles west of Le Câteau. Apparently the panzer regiment would not be ready to move until much later in the day, but Rommel was not about to wait. A composite battle group named Battalion Paris and consisting of mostly motorized infantry along with a few tanks and self-propelled flak guns, was dispatched. Throwing up a cloud of dust and firing occasionally, the column of mostly soft-skinned vehicles managed to convince the defenders they were facing a major armored assault. By nightfall on the 18th the town had been captured.

The 19th was spent regrouping and allowing the exhausted panzer crews to rest. Rommel, meeting with Hoth, demanded that he be allowed to make another night attack to seize the high ground south of Arras. Hoth did not think the troops sufficiently rested but was persuaded by Rommel’s reasoning that a successful night attack would mean fewer casualties.

Night Attack at Arras

In the early morning darkness of the 20th, the panzers were again on the move with Rommel characteristically in the lead. They reached the village of Beaurains, about two and a half miles south of Arras, at about 5 am. As had happened during his daring Avesnes raid, the motorized infantry regiments did not maintain contact with the panzers, falling well behind. Rommel again retraced his steps, attempting to make contact with them, and again was nearly captured.

Horne wrote, “French cavalry tanks [were] infiltrating across his lines of communication. These knocked out Rommel’s accompanying tanks and for several hours he and his Signals Staff were surrounded.” The rest of May 20 was spent clearing up the situation and bringing the infantry and artillery forward.

Units of the SS Totenkopf (Deaths Head) Division were coming up on his left to help cover that flank. The 5th Panzer Division would be coming up on his right, but for the moment he decided to cover that flank with infantry and artillery. The armored reconnaissance battalion was in the rear, most likely for the division’s logistical “tail,” given the problems of the previous days.

There were rumors of British and French divisions concentrating near Arras, but given all that had transpired so far Rommel dismissed them and continued with his own plans. The 25th Panzer Regiment would lead the advance around Arras to the northwest. Meanwhile, the tanks of Guderian’s and Reinhardt’s corps were pacing Rommel’s troops. Guderian’s 2nd Panzer Division reached the English Channel at Noyelles-sur-Mer around 8 pm. A narrow panzer corridor now split the Allies in two.

The British Counterattack

Some 250,000 British and French soldiers had been cut off from their main supply bases in the interior of France. Britain’s prime minister, Winston Churchill, had been on the job less than two weeks. Even so, he instinctively grasped there was an opportunity. He likened the German panzer divisions, far out in front of the forced-marching infantry, to a tortoise sticking its head out of its shell.

At his behest, Sir Edmund Ironside, chief of the Imperial General Staff, arrived at British Expeditionary Force (BEF) headquarters in northeastern France on the morning of May 20. Meeting with Lord Gort, the commander of the BEF, he indicated that in spite of recent events the British government was completely hostile to the idea of withdrawing from the Continent. Instead, he suggested Gort ought to stage a breakout to the southwest of a town named Arras.

(It is worth pointing out that Gort himself had held the position of CIGS prior to the outbreak of the war in 1939 and his appointment to command the BEF. Up until this point in his career he had never commanded a force larger than a brigade.)

Gort was skeptical. He could ill afford to draw off any of the seven divisions currently occupying the main front on the Escaut, lest he create a gap and lose contact with the already shaky Belgian Army on his left. He agreed the panzer corridor must be cut before the German infantry could catch up to reinforce it, but, he insisted, it would have to be a predominantly French operation. The best he could do at the moment, he told Ironside, was continue with an already planned counterattack by two divisions advancing south of Arras. The attack he envisioned, to be led by Maj. Gen. H.E. Franklyn, commander of 5th Infantry Division, was to cut German communications and block the roads south from Arras.

Major General Giffard le Quesne Martel, commander of the British 50th Infantry Division, had been selected to lead the attacking troops. As planned by Martel, the advance would be carried out by two mobile columns, each to consist of a tank battalion, an infantry battalion from the 151st Brigade, a battery of field artillery, and a battery of antitank guns, with a company of motorcyclists for reconnaissance. Fifty-eight Mark I and just 16 Mark II tanks were all it could muster for the attack. Many were in urgent need of a thorough overhaul, particularly their treads, which would crack and break after only

limited use.

The attack was destined to be severely handicapped. According to author George Forty, it “suffered from a complete lack of air support, had little artillery support, no infantry/tank radio communications, [the units had] never operated together before meeting in the concentration area and worst of all, had left in such a hurry that proper orders had never been passed down to individual tank commanders.” French participation would be limited to about 60 tanks from a cavalry corps covering the western flank of the right-hand column.

Rommel’s Gun Crews Repel the Attack

Rommel had given orders for the 25th Panzer Regiment to advance northwest of Arras toward Lille via Acq, a small village on the north bank of the Scarpe River. Observing the panzers forming up, he had no doubt this new thrust into enemy territory would be as successful as all those the regiment had launched in the preceding days. He wished to accompany it in person but, once again, the infantry had been slow to follow up, so he hastened back in search of von Bismarck’s 7th Motorized Infantry Regiment. It was nowhere to be found.

Instead, Rommel came across a portion of the 6th Motorized Infantry Regiment on the road between Ficheux and Wailly. Accompanying it he arrived in Wailly only to find the German forces in the streets in chaos. Tanks from the 7th Royal Tank Regiment, part of Martel’s right-hand column, were closing on the northern edge of the village from two directions, and their fire was creating havoc.

The situation, Rommel wrote, was an “extremely tight spot,” the retreating infantry sweeping up gun crews along with them. Immediate action was required. With the help of his aide, Joachim Most, Rommel rallied the gun crews and brought every available weapon into action. It was Rommel’s opinion that only heavy and rapid fire from every available gun, both antitank and antiaircraft, could reverse the situation.

Rommel’s life was certainly in great danger at this time. Most was killed only a few feet away just as the British began to withdraw. At another point Rommel and his telegraphist were cornered in a shell hole by a British tank. Instead of killing or capturing him, the tank crew exited the tank and gave themselves up. The driver had been killed, and the tank was crippled.

Rommel was deeply involved in deploying the 20mm antiaircraft guns at his disposal to repulse Martel’s right-hand column. He had no influence on the halting of the left-hand column, which was stopped in its tracks by 105mm and 88mm guns firing over open sights as the tanks of the left-column broke into the open country at Beaurains. One 88mm battery claimed to have destroyed nine tanks. Rommel spoke by radio at 7 pm with the 25th Panzer Regiment, which had reached its objectives and was waiting for the rest of the division. He ordered it to turn southeast and attack both Walrus and Duisans during the evening. It ran afoul of the infantry and antitank guns that had been detached there, eventually broke through them, and then engaged in a fierce tank duel south of Agnez as it pulled back to its start line. Seven British tanks were knocked out at a cost of nine German.

Casualties

The war diary of the 7th Panzer Division admits the following losses on May 21: 89 killed, 116 wounded, and 173 missing. This was four times as many losses as the division had suffered during the breakout from the Meuse. The 25th Panzer Regiment had lost as many as 30 vehicles, including six Czech PzKpfw 38(t) and three PzKpfw IV tanks. The Totenkopf Division recorded losses of 39 dead, 66 wounded, and two missing. The British claimed 400 prisoners, a total that does not match German figures. It is possible the number of German missing was deliberately under-reported.

British and French casualties had, however, been just as heavy, particularly in equipment. Of the 58 Mark I tanks only 26 remained, and of the 16 Mark II tanks only two remained. The rest, many of which needed maintenance, were harassed by German Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers.

Rommel Maintains the Offensive

In the days following the engagement at Arras, Rommel continued to push north, crossing the la Bassee Canal west of Lens, and at midday on May 26, he was given temporary command of the tanks in 5th Panzer Division for the assault toward Lille. Between May 27 and June 1, Rommel helped establish defensive positions outside Lille, fending off French attacks before being relieved by German infantry.

Summoned to see Hitler on June 2 while his division refitted for the second phase of the campaign, Rommel proudly wrote his wife that during the meeting on June 3 he was the only divisional commander who had been allowed to accompany Hitler. For his part, Hitler told Rommel, “we were all worried for you during the attack.”

The 7th Panzer Division would enjoy another run of virtually uninterrupted success the moment the German invasion was resumed on June 5. The French had adopted a defense in depth by this time and occasionally inflicted sharp losses on the advancing Germans, but they had lost most of their best troops and equipment and the BEF had been evicted from the Continent. German victory was only a matter of time. Breaching the French line at the Somme River between Abbeville and Amiens, the rapid advance quickly transformed into a rout.

Rouen was reached on June 8; St. Valéry, between Le Havre and Dieppe, on the 11th; and Cherbourg on the 18th. Rommel, writing home to his wife from Rennes on June 21, described the second phase of the campaign as resembling a pleasant “lightning tour of France.” When the armistice between Germany and France went into effect on the 25th, the 7th Panzer Division was fewer than 200 miles from the Spanish frontier. During the execution of Plan Gelb, at the cost of less than 2,500 casualties and 42 tanks destroyed (highest of Germany’s 10 panzer divisions), Rommel’s division had captured 97,648 prisoners, 277 field guns, 64 antitank guns, 458 tanks and armored cars, and more than 4,000 trucks in addition to enormous amounts of supplies.

“The Greatest Battle of Annihilation of All Time”

Germany’s campaign in France and the Low Countries in May and June 1940 has been characterized—both at the time and since—as “the greatest battle of annihilation of all time.” Author John Ellis wrote that the German Army “had defeated a highly rated enemy, superior in both numbers and equipment, in just 46 days.”

The armies of Holland, Belgium, France, and Britain had been routed by a German Army lacking both material and numerical superiority and in spite of their having been allowed nine months in which to prepare their defenses in a theater of operations large enough to have afforded ample opportunity to buy time through a considered strategic withdrawal.

Germany, for its part, misunderstood the basis of its astonishing victory and underestimated the willingness of the Allies to fight on. Hitler became convinced that his armies could not be beaten. Rommel, who at the time had no idea Hitler’s thirst for conquest was nearly unquenchable, probably expected the war to be over in 1940. He wrote, “How wonderful it’s all been.”

The Ghost Division

The exploits of the Gespensterdivision (Ghost Division), as the Germans called 7th Panzer, or la division fantôme (the phantom division), as the French referred to it, during the stunning conquest of France delighted Rommel’s benefactors and virtually assured further advancement. To drive the point home Rommel spent part of the summer of 1940, at Goebbels’ request, assisting in the production of the propaganda film Victory in the West. The counterattack at Arras is the only Allied offensive action mentioned in the entire film.

Time was also spent preparing for the crossing of the English Channel and the invasion of Great Britain, code-named Operation Sea Lion, but the invasion was canceled when the necessary precondition—air superiority over the Channel and southern England—was never achieved.

Rommel also published the war diary of the 7th Panzer Division in book form, a copy of which was presented to Hitler by Rommel’s friend, Rudolf Schmundt. Hitler was impressed to the extent that he wrote a letter, dated December 20, 1940, telling Rommel, “You can be proud of your achievements.”

Promotion came in January 1941, when Rommel was elevated to the rank of lieutenant general and sent to Libya to spearhead Operation Sonnenblume (Sunflower) as commander of the Afrika Korps. There, in North Africa, he would eventually earn his field marshal’s baton and cement his reputation as the Desert Fox.

Originally Published September 2010

My husband is a History “buff”. I printed this article, if he likes, we might consider ordering the magazine.