By Major Dominic J. Caraccilo

On January 24, 1964, Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) Headquarters in Saigon issued General Order 6, creating a highly secretive new organization to execute clandestine missions against the Viet Cong. Euphemistically called the “Studies and Observation Group,” or more simply SOG, this organization, under the auspices of the Pentagon, would execute a wide array

of covert activities including dispatching numerous spies to North Vietnam and creating a sophisticated “triple-cross” deception program. Additionally the next eight years would see the SOG organizing and participating in “black” psychological warfare through a fabricated guerrilla movement; manipulating North Vietnamese POWs and kidnapped citizens; and conducting operations on the Ho Chi Minh Trail to kill enemy soldiers and destroy supplies.

The Secret War Against Hanoi: Kennedy’s and Johnson’s Use of Spies, Saboteurs, and Covert Warriors in North Vietnam, by Richard H. Schultz, Jr. (HarperCollins Pub., NY, December 1999, 398 pages, photographs, notes, and bibliography; $27.50) is a comprehensive look behind the “shroud of secrecy” that for years had kept the largest covert operation executed by Washington during the Cold War buried deep in the vaults of the Pentagon and inaccessible. As early as 1961, President John F. Kennedy, disenchanted with the Central Intelligence Agency’s abilities to run large covert operations against Hanoi, directed the Pentagon to take over and escalate the effort. As a result, senior military leaders, venturing into “untested waters,” began to grudgingly integrate a series of covert missions into their war plans. The result was arguably mixed.

Author Richard H. Schultz, Jr., Director of the International Security Studies Program and Associate Professor of International Politics at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy Tufts University, bases this intriguing account on a unique evidentiary foundation of primary sources that includes interviews with senior officials, former SOG operators, and 1,500 pages of newly declassified sensitive documents. Given the present-day global environment where there is the need for special operations to defeat terrorism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, this book is extremely important because it is immersed with lessons. The future of our efforts to ward off emerging threats will depend in large measure on how well we learn the lessons presented in The Secret War Against Hanoi.

Operating in the “denied” territory of North Vietnam, the SOG’s accomplishments could have been greater had it not been restrained by “jittery Washington policy makers,” who, unfortunately, were more concerned with the trouble asymmetric-type operations could create if exposed, rather than the problems such activities could cause Hanoi if executed effectively. Much to contrary belief, the counterinsurgent operations against Hanoi were indeed closely supervised by the White House, dispelling the claim that agencies ran rogue operations without the knowledge or supervision of the White House. However, by the time LBJ became President, he insisted on even more oversight and, consequently, the SOG became a micromanaged organization. Therefore, SOG leaders struggled to meet the charter imposed on SOG by the President.

Taking on an “if they can do it, so can we” attitude about counterinsurgent operations against the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese government, the SOG had, unfortunately, some spectacular blunders, the most devastating being the failure of agent operations. Of the approximately five hundred agents sent into North Vietnam to establish spy networks, Hanoi caught every one and “doubled several back for years.” Much of the blame for this goes to Washington since it had restrained the agents from destabilizing the Hanoi regime. Nor would it allow the SOG to nurture a resistance or guerrilla movement against the North Vietnamese government since “it was too much of a political risk” considering the Chinese “wildcard” and the possibility of further destabilization in the region.

While the SOG had many disasters, it had its share of successes. However, those successes were never capitalized upon since both the military and the government paid insufficient attention to calculating the impact of the actions, short of counting the number of operations initiated—a mark not worthy of measurement. In short, the experiences provided to the SOG during the Vietnam War set the stage for an understanding of operations requiring “a greater ability to deal with guerrilla forces, insurrection, and subversion.”

Throughout the Cold War almost every president, beginning with Harry Truman, was drawn to the use of covert action. In The Secret War Against Hanoi, Shultz has credited the SOG during Vietnam as revitalizing how special operations should be conducted. As a result, and because of the work by great men that go by the name of Singlaub, Kingston, Trainor, Simons, Meadows, Andrews, and Krulak, this nation has formed agencies like the U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCM) which focuses on those lessons learned from the operations the SOG conducted and has since refined its organizational and training bases so that the United States is better prepared to conduct like missions in the future.

The Secret War Against Hanoi: Kennedy’s and Johnson’s Use of Spies, Saboteurs, and Covert Warriors in North Vietnam is, beyond a doubt, the all-encompassing, smartly compartmentalized book on the history of U.S. Special Operations in Vietnam with a focus on its struggles and successes, and an honest look at the way “unconventional warfare” may be fought in the future. While the debates surrounding the conduct of the war against North Vietnam remain as contentious as when the war was fought, this study provides an invaluable contribution to understanding this controversial and complex war.

Recent and Recommended

After the Trenches: The Transformation of US Army Doctrine, 1918-1939, by William O. Odom, Texas A&M University Press, 1999, 282 pages, $44.95.

William O. Odom functionally decomposes the lessons learned from World War I and how the army integrated those lessons into the Field Service Regulations (FSR) of 1923. This work provides connectivity between the world wars in a method not used before. In short, Odom provides an analysis of how the doctrine writers of the time capitalized on lessons learned from World War I to prepare for the next war. In addition, he explores the impact foreign militaries and parochial politics had on the development of the doctrine that arguably won the subsequent war. After the Trenches fills a currently existing void about the challenges the nation had more than 70 years ago in developing its needs to an ever-evolving and threatening environment. It will no doubt broaden the perspectives of our army’s leadership today as we struggle through the identification of current-day threats and the military’s structure to defeat them.

Jungle Dragoon: The Memoir of an Armored Cav Platoon Leader in Vietnam, by Paul D. Walker, Presidio Press, 1999, 256 pages, $24.95.

In September 1966, while operating in the jungles of War Zone C just north and east of Saigon, the U.S. Army pitted the M-48 tanks of the 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, better known as “Quarter Horse,” against the forces of the Viet Cong’s 9th Division. Although this is not the image that springs to mind when thinking of the Vietnam War, armored cavalry forces were used extensively throughout the country.

Jungle Dragoon is the latest of Presidio’s superior military memoirs reporting the Vietnam experience of a career armored officer whose first combat tour was with the famed “Big Red 1.” Retired colonel Paul D. Walker, better known during his Vietnam tour as “Dragon Charlie One Six,” was a 23-year old army second lieutenant stationed in Germany when he received orders for Vietnam. In his book he presents what pundits would term a “blood-and-guts, shoot-’em-up memoir” of Vietnam. However, it is Walker’s particular perspective, that of the viewpoint of an armored cavalry platoon, that makes this memoir so unique.

The Victors: Eisenhower and His Boys: The Men of World War II, by Stephen E. Ambrose, Simon & Schuster, 1999, 396 pages, $28.00.

Without these “victors,” the men who so courageously gave of themselves for their country and for the freedom of mankind, the world would be a much different place today. The “victors” spoken of in this book are the leaders and warriors of the Allied coalition who fought on the land, sea and air to defeat the German Wehrmacht in World War II. The Victors is at once a tribute to those who fought for the Allies in the last great war and recognition for the warrior/statesman seen in Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Overlord Commander. A protégé of Ike for nearly his entire life, Ambrose continues to pay tribute to Eisenhower in The Victors by combining the work of his “greatest hits” with focusing on what he deems the most important part of World War II: The perspective of the front-line troops. Furthermore, it is a fitting sequel to a master storyteller’s quest to make known the contribution these great men made to the freedom of mankind.

Vietnam: The Necessary War: A Reinterpretation of America’s Most Disastrous Military Conflict, by Michael Lind, The Free Press, 1999, 297 pages, $26.95.

“One of the central claims of opponents of the Vietnam War was the assertion that American policymakers tragically mistook spontaneous nationalist movements in [Indochina] as evidence of the existence of an international communist conspiracy.” Michael Lind refutes this assertion in Vietnam: The Necessary War: Grand Strategy, Domestic Politics, and the American War for Indochina by claiming that, where communism takes root in Asia, its strengths arise through locally generated social, economic and political factors. In short, he accepts the domino theory, but only in a “regional” perspective.

In Vietnam: The Necessary War, Lind argues that it was “necessary for the U.S. to escalate the war in the mid-1960’s in order to defend the credibility of the U.S. as a superpower.” However, he goes on to establish that it was necessary for the United States to forfeit the war after 1968 in order to preserve the American domestic political consensus in favor of the Cold War on other fronts. “Indochina was worth a war, but only a limited war—and not the limited war that the U.S. actually fought.” He draws the correct conclusion by calling the Vietnam conflict a “failed campaign in a successful war against imperial tyrannies.” He truly believes that the “anti-Vietnam War orthodoxy is so exaggerated, and so implausible, that it is certain to change as younger historians uninfluenced by the partisan battles of the Vietnam era write a more accurate and dispassionate history.”

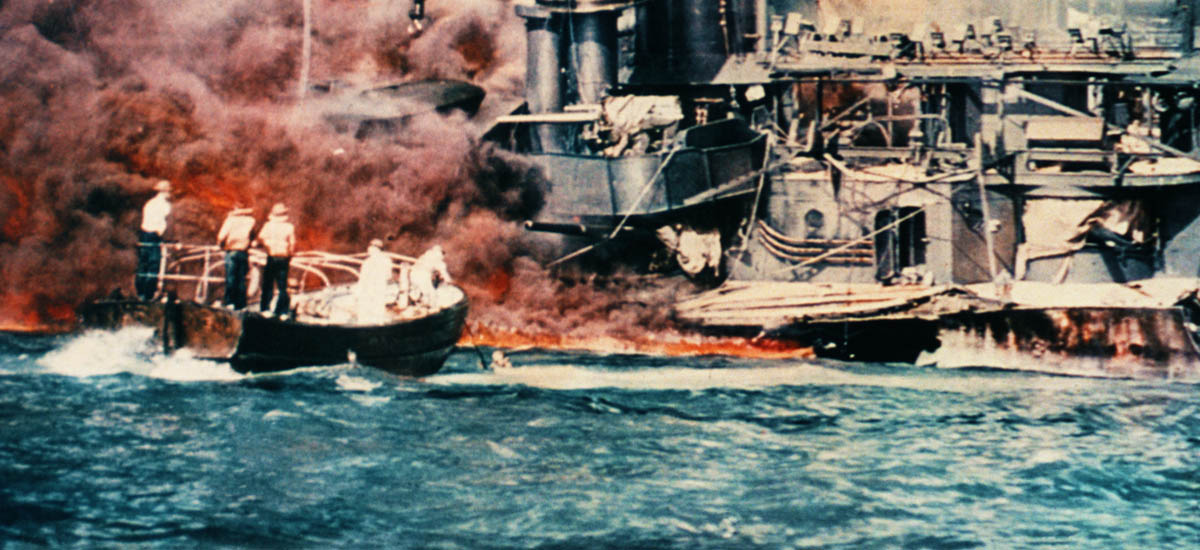

Mr. Michel’s War: From Manila to Mukden: An American Navy Officer’s War with the Japanese, 1941-1945, by John J.A. Michel, Presidio, 1998, 297 pages, $26.95.

This book is not just another “guest of the emperor” memoir, but rather a down-to-earth encapsulating chronology of a young warrior setting out to survive his stint in the Navy. Unfortunately for him, Michel’s time of national service came at the same time the Japanese decided to wage war against the United States. Setting off to the Pacific Rim in 1941, Michel tells of a journey to prewar Japan, China and of course, the “Pearl of the Orient,” Manila. In stark contrast to the beginning of the book is the tale Michel tells of being lost at sea only to be picked up and sent to prison camps for the duration.

Much has been written about the battles leading to the fall of Bataan and the subsequent internment of American and other Allied soldiers by their Japanese captors. Michel’s memoir is unique in that it is about a naval officer, an anomaly to the Japanese POW genre. Additionally it is special, since it was written in 1948, only to be released for publication some 50 years later. Therefore, the emotions of the time just subsequent to his release as an enemy prisoner of war are intact and not blemished by an inherent inability to recall details as often seen in so many memoirs.

In Brief

U.S. Special Operations Forces in Action: The Challenge of Unconventional Warfare, by Thomas K. Adams, Frank Cass Publishers, 1998, 360 pages, $57.50.

This book is an incredible work that explores every facet of the U.S. Special Operations world. It also honestly confronts what “unconventional warfare” may look like in the years ahead.

Seven Roads to Hell: A Screaming Eagle at Bastogne, by Donald R. Burgett, Presidio, 1999, 225 pages, $24.95

Screaming Eagles in Bastogne. There isn’t a better World War II story to be told. What makes this particular story good, however, is that it’s from someone who was there and, even better, it was written soon after the secession of hostilities in Europe while the events were still fresh in his mind.

Gray Ghost: The Life of Colonel John Singleton Mosby, by James A. Ramage, University Press of Kentucky, 1999, 432 pages, $30.00.

This is most likely the first full-scale biography of legendary Confederate raider John Singleton Mosby. With an emphasis on his Civil War exploits, Ramage offers a well-documented volume that charts the progress of the “Gray Ghost” from early childhood to fame as an icon in the Confederate Army during the Civil War as, quite possibly, the first Special Forces leader in the U.S. Army. A first-rate biography of the South’s most mythological and celebrated Civil War hero.

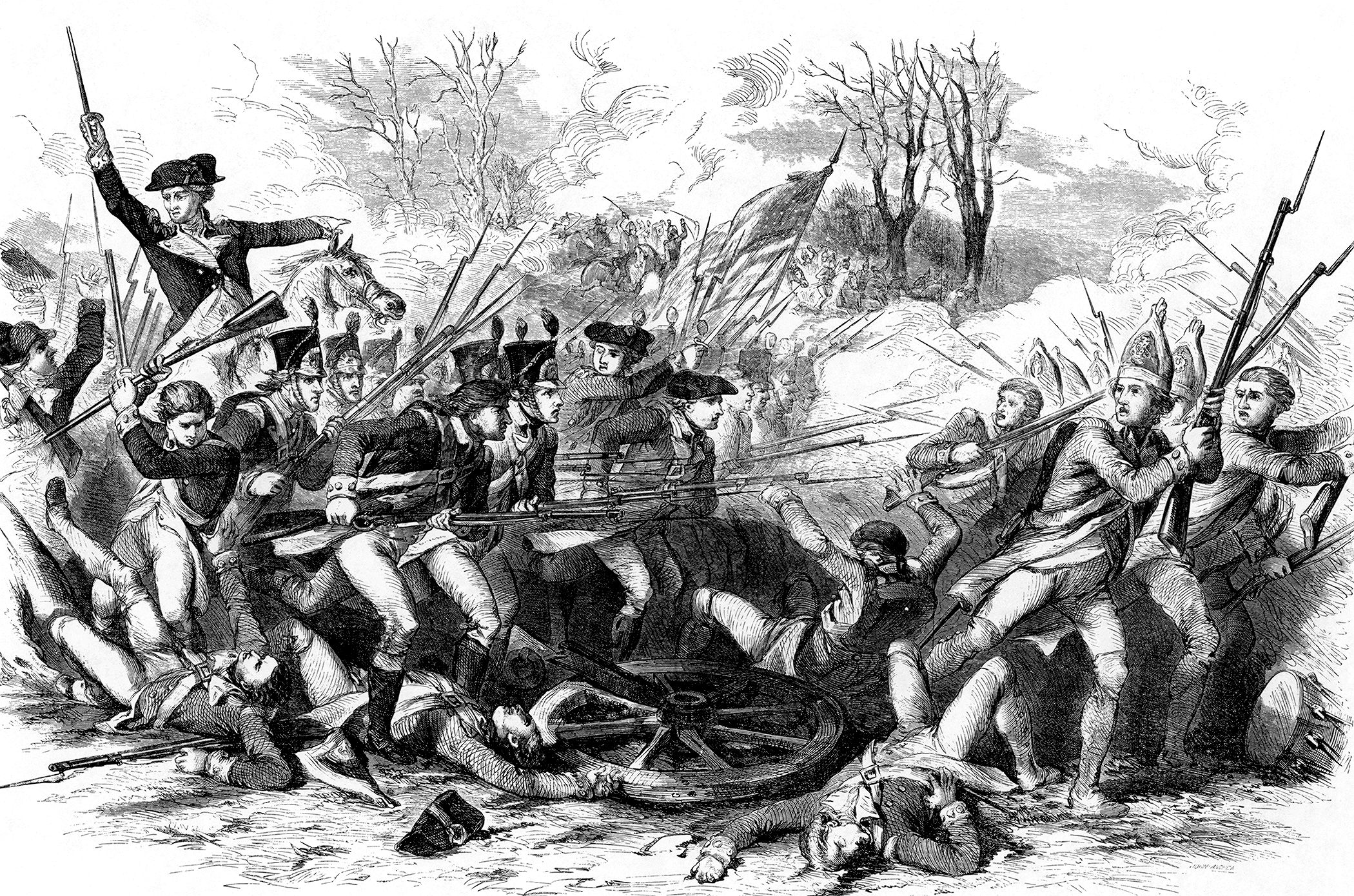

Engineering the Revolution: Arms & Enlightenment in France, 1763-1815, by Ken Alder, Princeton University Press, 1999, 496 pages, $24.95.

By documenting how new gun technology was exploited by 18th-century revolutionaries in France and also by Napoleon, Ken Alder clearly demonstrates how material artifacts have emerged as the negotiated outcome of political struggle. This truly ambitious book ties the making of weapons to the evolution of industrial practices, bringing to life the manufacturing of arms during the French Revolution.

Code-Name Bright Light: The Untold Story of U.S. POW Rescue Efforts During the Vietnam War, by George J. Veith, The Free Press. 1998, 320 pages, $25.00.

It has been more than two decades since the end of the Vietnam War and the POW/MIA issue continues to strike controversy in many circles. This is one of the reasons author and former Army captain George J. Veith wrote Code-Name Bright Light: The Untold Story of U.S. POW Rescue Efforts During the Vietnam War. It is apparent that Veith believes strongly that the military made a sincere effort to rescue captured troops, and argues his case well, yet he also reveals a troubled operation that did not liberate a single soldier due to a combination of its own incompetence and clever Viet Cong tactics.

We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American Nurses Trapped on Bataan by the Japanese, by Elizabeth M. Norman, Random House, 1999, 327 pages, $26.95.

We Band of Angels is a tremendous tribute to the heroes of Bataan and to women who have served in the military. Norman’s well-written and meticulously researched account of the American struggle in the Philippines at the onset of World War II reads like a novel, for it brings out the grim realities of the Pacific War and the POW experience under the Japanese to all-too-vivid life. Yet, her ability to piece together this account in the form of world-class nonfiction shows her mastery in writing her second book about women at war.

The Grand Strategy of Philip II, by Geoffrey Parker, Yale University Press, 1998, 446 pages, $35.00.

Geoffrey Parker is cited as a leading authority on the diplomatic and military history of early modern Europe. He validates that claim in his work, an “intellectual tapestry” illuminating Spain’s Philip II’s reign during the 16th- century. Philip’s crown included Portugal; the Netherlands; almost all of Italy; the African portions of Tunis, Tangier, Guinea, and Angola; holdings in India; the Philippines; and many colonies in the Western Hemisphere. Parker offers a revisionist view of Philip’s “Grand Strategy” and offers great insights into the geopolitical and military power of his monarchy.

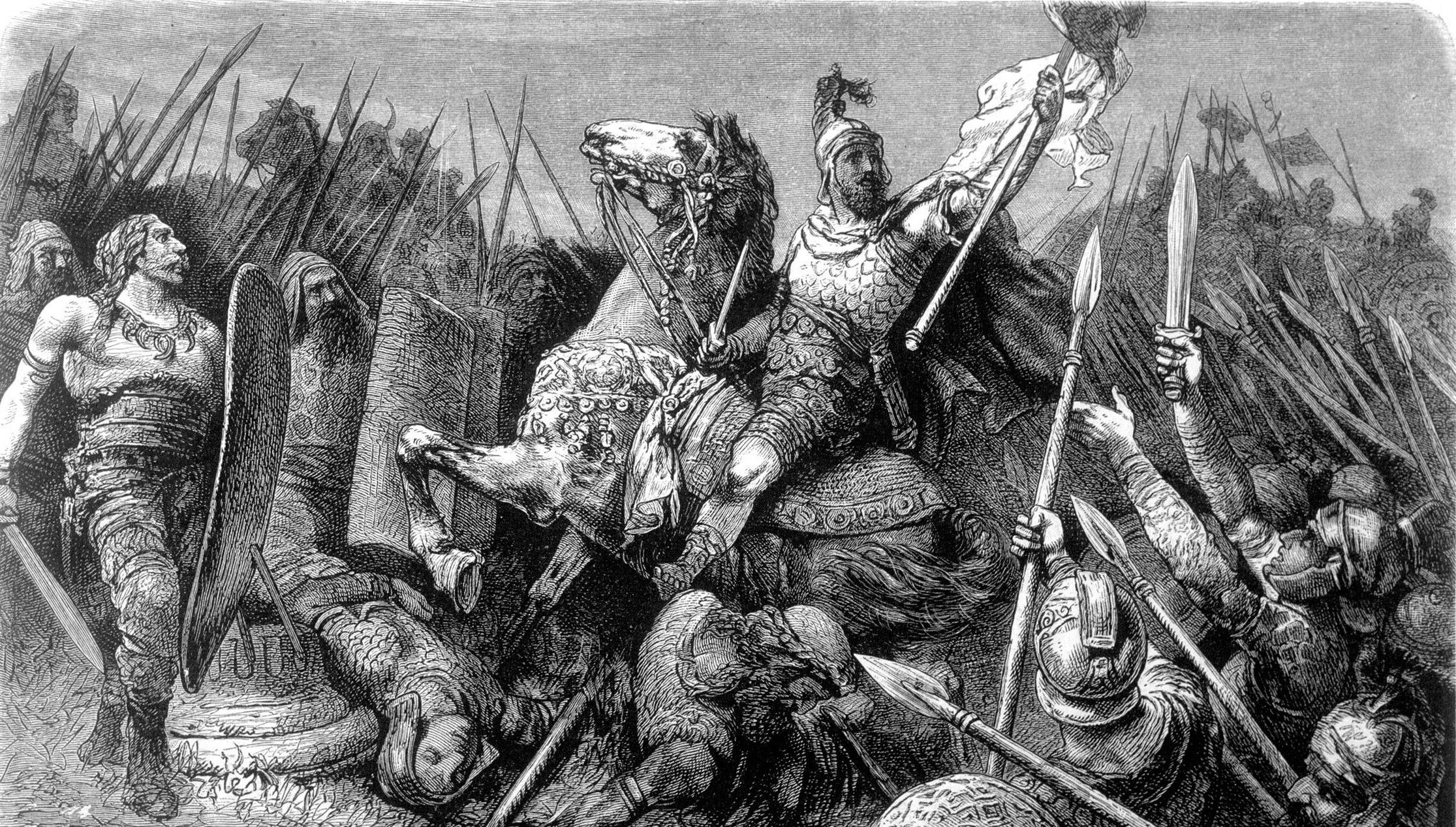

Ancient Siege Warfare, by Paul Bentley Kern, Indiana University Press, 1999, 448 pages, $35.00.

Ancient siege warfare was a form of total war that often ended in the destruction of an entire city and the massacre or enslavement of its population. “Leaders from Alexander the Great to Julius Caesar all commanded great sieges that ended in fearsome slaughters.” The ancient Hebrew prophets and Greek poets described siege warfare as a world without limits or structure or morality, and in which men violated deep-seated taboos about sex, pregnancy and death.

In Ancient Siege Warfare, Paul Bentley Kern, professor of history at the University of Indiana Northwest, examines siege warfare from its earliest origins. He also delves into the fortifications and machinery used in defense and offense. Some of the sieges he presents are ones involving Israelites, Persians -– and other Middle Eastern peoples – Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments