By Al Hemingway

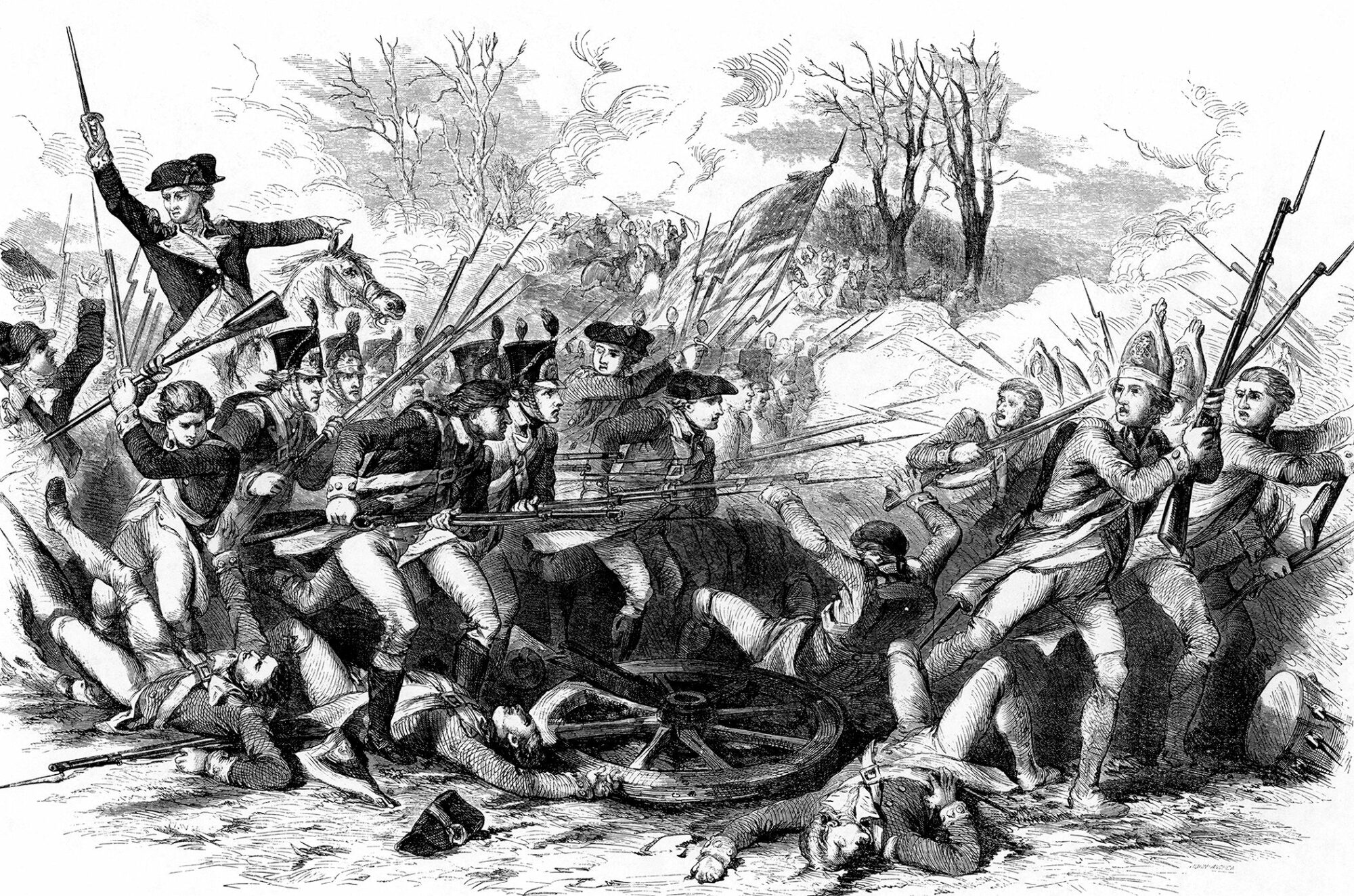

When historians discuss the American Revolution, they give scant attention to the hard fighting that occurred in the southern states. When British General John Burgoyne suffered a humiliating defeat at Saratoga in 1777, Sir Henry Clinton and his strategists decided to invade Dixie, starting with Georgia, then moving northward and occupying South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia.

In his latest book, The Revolutionary War in the Southern Back Country (Pelican Publishing, Gretna, Louisiana, 2008, 380 pp., maps, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover), author James K. Swisher traces the origins of the British invasion of the southern states and how a new type of combat, as well as military leaders, emerged from the bloody fighting.

In his latest book, The Revolutionary War in the Southern Back Country (Pelican Publishing, Gretna, Louisiana, 2008, 380 pp., maps, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover), author James K. Swisher traces the origins of the British invasion of the southern states and how a new type of combat, as well as military leaders, emerged from the bloody fighting.

The southern back country was a vast territory that stretched from Maryland to the western sections of Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia. Settlers, hearing of the lush farmland, soon made their way into the region to raise their crops. It was not an easy life; only the roughest and most persistent could survive the harsh countryside. These hardy pioneers had to stave off Indian attacks as well as their British masters as the revolution neared.

These backwoodsmen honed their fighting skills in several prior military engagements before hostilities between Great Britain and the restless colonies erupted. In the fall of 1774, Virginia Governor John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore, provoked a war with the Shawnees to acquire more land,

predominately in Ohio. What became known as Dunmore’s War depleted the Virginia militia and ultimately helped the Virginia loyalists. By 1776, Dunmore was forced to flee and return to England.

That same year, another series of pitched battles against the Cherokees began. From this campaign, three gifted military leaders would emerge: Francis Marion, better known

as the “Swamp Fox,” Thomas Sumter, and Andrew Pickens, a stern Presbyterian minister. All of these men had learned how to fight by utilizing new tactics while engaged against the Cherokees. Such tactics as hit-and-run attacks, ambushes, and raiding behind British lines would prove quite effective in defeating the redcoats.

Another dynamic personality to surface at that time was Daniel Morgan. Born in New Jersey, Morgan left home and made his way to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia to settle. A tough and rowdy individual, he soon became accustomed to the Spartan life of the southern back country, accompanying Burgoyne’s troops to Fort Pitt during the French and Indian War. The undisciplined Morgan was soon in trouble, however, and received hundreds of lashes from a British cat-o-nine tails. From that day forward, he hated the British.

When he was transferred to the South after participating in the battles for Quebec and Saratoga, Morgan disobeyed orders from department commander General Nathaniel Greene and confronted the enemy at Cowpens in South Carolina. On January 17, 1781, Morgan’s army fought a pitched battle against brutal Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s command. Using his Virginia long rifles to inflict massive casualties, he enveloped the redcoats and won a decisive victory.

Southern leaders would soon whip the British again at the Battles of Kings Mountain and Guilford Court House. Clinton’s scheme to seize each state and isolate the American army in New York would fizzle because of bold officers such as Morgan. As Swisher states, “From Dunmore’s War and the Cherokee War came the experience that produced worthy foes for the British campaign of 1780.”

Volunteers on the Veld: Britain’s Citizen-Soldiers and the South African War, 1899-1902 by Stephen M. Miller, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 2007, 236 pp., maps, photos, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Volunteers on the Veld: Britain’s Citizen-Soldiers and the South African War, 1899-1902 by Stephen M. Miller, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 2007, 236 pp., maps, photos, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

At the outbreak of the Boer War in October 1899, Great Britain had over a quarter of a million men in uniform. Ten thousand of these regulars were already stationed in South Africa and another 12,000 were quickly dispatched to the region as reinforcements.

In December 1899, however, the British Tommies suffered three humiliating defeats at the hands of the Dutch-speaking Afrikaners. At Stormberg, Magersfontein, and Colenso, the Boer forces inflicted thousands of casualties on the Brits. When news reached England, the populace were in disbelief that “the flower of the British Army [could be] outmaneuvered and repulsed three times in one week by undisciplined Boer farmers.” The public soon referred to it as Black Week.

The call went out for volunteers to augment the army in South Africa, and on Christmas Eve 1899, a royal warrant was decreed creating the Imperial Yeomanry. Recruits came from the standing yeoman units already serving. Between February and April 1900, thousands of volunteers poured into the country and were immediately dispatched to the Transvaal to fight the Boers.

Although there were setbacks at times, the volunteer forces performed reasonably well and contributed to England’s victory over the elusive Afrikaners. The British involvement in South Africa closely resembled that of the United States in Vietnam and present-day Iraq, wars with no clear objectives or decisive strategy to achieve victory and guarantee safe withdrawal.

Despite this, the British volunteers who served in the harsh countryside known as the Veld were instrumental in assisting the regular army in time of conflict. Using firsthand accounts from letters and diaries, historian Stephen Miller illustrates the reasons why young, middle-class Englishmen volunteered for such hazardous duty. They donned the uniform and fought a bloody guerrilla war for queen and Empire and achieved notoriety back home as well.

“The South African War was a pivotal event in the history of Great Britain, its empire, and its military,” writes Miller. “Citizens were transformed into soldiers; conventional war gave way to low-intensity conflict; and as the nineteenth century ended, the twentieth century ushered in modern warfare.”

Co-ed Combat: The New Evidence That Women Shouldn’t Fight the Nation’s Wars by Kingsley Browne, Sentinel, New York, New York, 2007, 352 pp., notes, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Co-ed Combat: The New Evidence That Women Shouldn’t Fight the Nation’s Wars by Kingsley Browne, Sentinel, New York, New York, 2007, 352 pp., notes, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Should women be allowed to serve in combat units and become directly involved in the fighting? This divisive topic has plagued the nation’s military for decades. Many believe it is time for true integration of the military. Just as African Americans were allowed to join the ranks of the military on equal terms, so should America’s female population.

Kingsley Browne, a law professor at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, does not think so and points out the possible pitfalls that await the military if complete integration of the armed services is achieved by allowing women to join combat units. Citing various sources, Browne dispels the myths that women possess the same upper-body strength as their male counterparts and that with the proper training women can achieve the same physical strength.

The author commends those women on active duty who have performed admirably during both Gulf Wars. He questions, however, statements made by our political leaders through the years concerning women in various wars. President Woodrow Wilson commented at the end of World War I in 1918 that the war could not have been fought if it had not been for the services of the women. Also, then Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney during the first Gulf War asserted that “women have made a major contribution to this effort.” Certainly, this was a statement that no one could deny. But then he continued: “We could not have won without them.” It was a typical Cheney misstatement, considering that women made up a mere 6.8 percent of the total force in the Gulf.

Under heavy pressure from politicians to change the system, military leaders are finding it increasingly difficult to keep disagreeing with them. Many officers will acquiesce rather than risk their careers. No matter what your beliefs, Co-Ed Combat is an intriguing account of this controversial subject. Accepting women in combat roles will continue to be a heated debate. If full integration becomes a reality, how will it affect our national defense? Can an army comprised of female GIs win a war?

Rampant Raider: An A-4 Skyhawk Pilot in Vietnam by Stephen R. Gray, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2007, 284 pp., notes, index, $32.50, hardcover.

Rampant Raider: An A-4 Skyhawk Pilot in Vietnam by Stephen R. Gray, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2007, 284 pp., notes, index, $32.50, hardcover.

There is no duty more hazardous then flying jet fighters from an aircraft carrier. It takes a special individual to master the intricacies of guiding a high-powered jet back onto the moving deck of a carrier after a bombing mission.

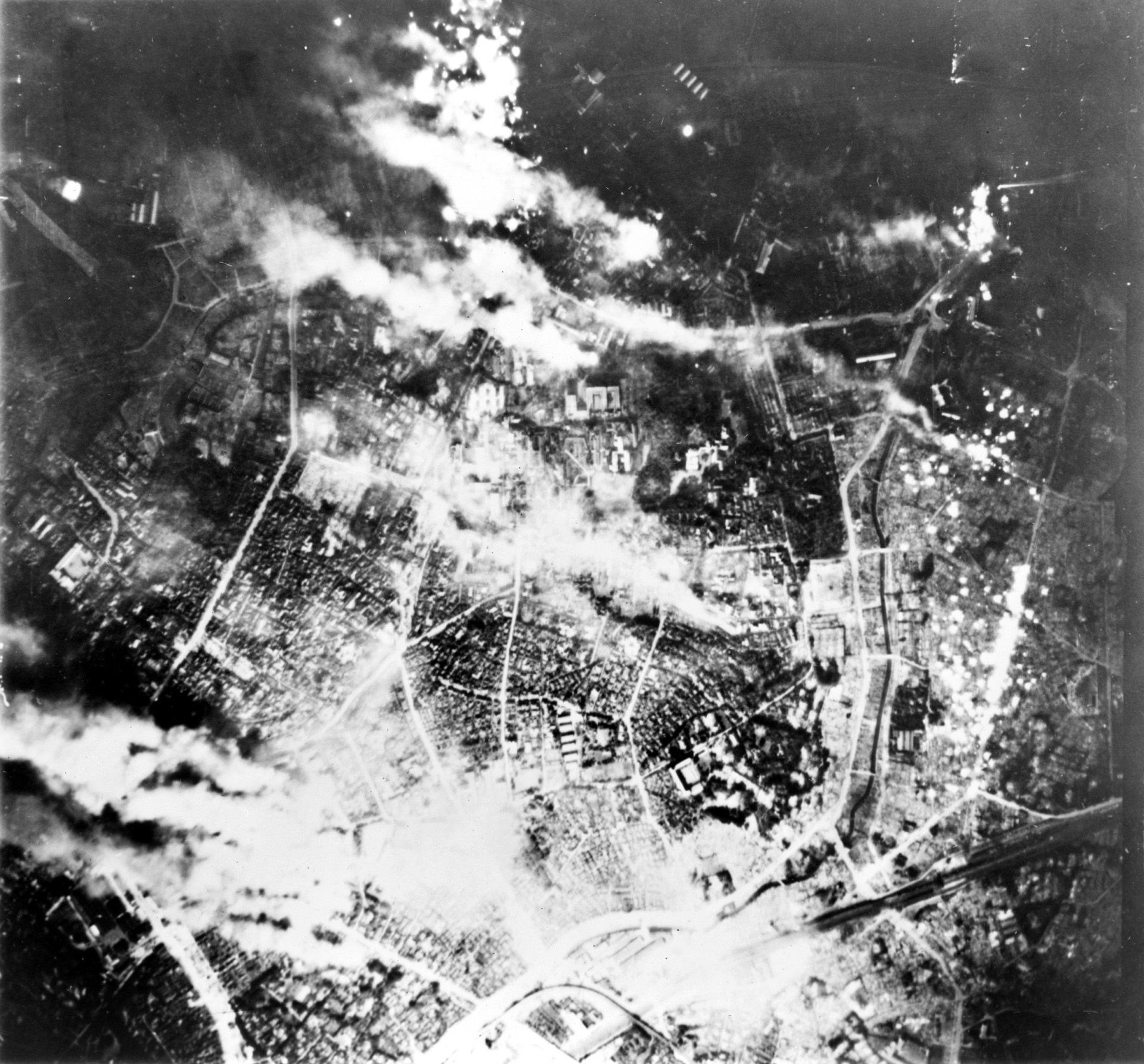

Author Stephen Gray performed this difficult task during his two cruises to Vietnam aboard the USS Bonhomme Richard in 1967 and 1968. Gray compiled an impressive 300-plus carrier landings and over 250 combat missions into North Vietnam. Gray gives a compelling account of his time in the cockpit flying the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk with VA-212, and of life aboard the Essex-class carrier during those years.

One chapter describes in detail his squadron’s role in destroying the Thanh Hoa thermal power plant in North Vietnam. After the strike, Gray and his comrades had the opportunity to view photographs taken by a reconnaissance aircraft just minutes after they had unloaded their bombs. “His photos showed the main power plant building to be cratered rubble, completely destroyed,” he wrote. “One of the steam boilers had been blasted several yards outside the confines of the power plant yard, and huge craters pocked the transformer field. It would be a long time before Thanh Hoa had any electricity.”

For those who enjoy reading about the air war in Southeast Asia, Rampant Raider is your kind of book. The Skyhawk was a true workhorse during the Vietnam conflict, and the author was in the thick of the action over the skies of North Vietnam.

War Stories of the Tankers: American Armored Combat, 1918 to Today by Michael Green, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2008, 319 pp., photos, $24.95, hardcover.

Many say that the infantry is the worst job in the military. But ask anyone who served in an armored unit, and they would probably disagree with that assessment. Being confined to such a small area was very uncomfortable for crew members. The ironclad machines were also very good targets, and heightened one’s chances of getting killed in combat.

As the title implies, author Michael Green has collected oral histories from men who served in armored units from World War I to the present. Tanks first appeared on the battlefields of World War I and were cumbersome, to say the least. The French Renault FT-17, used by the U.S. Army during the conflict, had a top speed of five miles per hour. The British Heavy Tank was larger and had a crew of eight, but its lack of a suspension system made for an extremely bumpy ride.

From these humble beginnings, the tank has evolved into a superior fighting machine. The M1A1 Abrams now being used in the Middle East can reach speeds of 40 miles per hour and sports a 1,500-horsepower gas engine. Its main armament is a lethal 120mm gun, a .50-caliber heavy machine gun, and a 7.62mm light machine gun. On both sides of the turret, the vehicle has smoke grenade launchers to shield its movement.

War Stories of the Tankers is an excellent book told by the men who manned tanks during wartime. From its infancy in the Great War to the high-tech ongoing conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan, the reader will understand what it is like to be a part of a combat tank crew.

Go If You Think It Your Duty: A Minnesota Couple’s Civil War Letters by Andrea R. Foroughi, Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul, MN, 2008, 336 pp., photos, index, $32.95, hardcover.

Go If You Think It Your Duty: A Minnesota Couple’s Civil War Letters by Andrea R. Foroughi, Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul, MN, 2008, 336 pp., photos, index, $32.95, hardcover.

It is always fascinating to read personal letters or diaries from soldiers who fought in our nation’s wars. Their insight and observations provide a valuable glimpse into another era, and are a welcome change from the often dry accounts of battles and campaigns where there is no mention of the common foot soldier. In such accounts, regiments, battalions, and companies are shifted like chess pieces, but these units were comprised of human beings, and their stories are valuable sources of a better understanding into America’s history. There was a plethora of correspondence during the Civil War. Both blue and gray wrote of their experiences during that turbulent time.

James Madison Bowler enlisted in the Union Army and served with the 3rd Minnesota Volunteer Regiment for four years. He was later given a commission and was discharged as a major with the 113th Colored Infantry. He penned hundreds of letters to his wife, Elizabeth “Lizzie” Caleff Bowler, describing camp life, people and battles.

Bowler’s strong sense of duty and patriotism is evident in his writings. Lizzie agreed that he should go off to fight and help preserve the Union. After the many months of separation, however, her patience was waning and she begged him to come home. This ongoing argument became the central theme in many of the letters.

Bowler survived the war and came home to Lizzie, dying in 1916 at the age of 78. Lizzie outlived her husband by 15 years, passing away in 1931 at the age of 90. Their letters to each other, however, will be with us forever.

Thermopylae 480 BC: Last Stand of the 300 by Nic Fields, Osprey Publishing, New York, New York, 2007, 96 pp., photos, maps, illustrations, index, $18.95, softcover.

Thermopylae 480 BC: Last Stand of the 300 by Nic Fields, Osprey Publishing, New York, New York, 2007, 96 pp., photos, maps, illustrations, index, $18.95, softcover.

The last stand of the Spartan force at the pass of Thermopylae is arguably one of the greatest stands in military history. Although the small band led by Spartan King Leonidas was defeated, they bought precious time for the other Greek states to prepare themselves against the Persian Army commanded by King Xerxes I.

For 72 hours, the heroic group repelled assault after assault, holding the vital strongpoint in central Greece until Ephialtes, a local resident, betrayed them and showed Xerxes a small path that would put his army in the Spartan’s rear. Although they eventually wiped out the defenders, the Persians sustained extremely heavy losses.

This newest edition into the Osprey campaign series of battles gives a good, concise account of the origins of the battle, the leaders, the battle itself, and its aftermath. As with all of Osprey’s books, this one is full of detailed maps, photographs, and paintings.

House to House: An Epic Memoir of War by Staff Sgt. David Bellavia with John R. Bruning, Free Press, New York, New York, 2007, 321 pp., photos, glossary, $26.00, hardcover.

House to House: An Epic Memoir of War by Staff Sgt. David Bellavia with John R. Bruning, Free Press, New York, New York, 2007, 321 pp., photos, glossary, $26.00, hardcover.

There is a multitude of books being published about the current situation in the Middle East. Although many that deal with the strategy—or lack of it—behind the fighting, others are written on a more personal level and concentrate on an individual’s tour in the combat zone.

House to House is a cut above many when it comes to frontline combat stories. The author, David Bellavia, was a member of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Infantry, 3rd Brigade, 1st Infantry Division. Known as Task Force 2-2, he and his squad participated in numerous operations in Iraq, including the horrific urban fighting at the insurgent stronghold in Fallujah.

Bellavia describes in graphic detail the close-quarter, house-to-house struggle to oust the determined terrorists from their hidden lairs within the city. His own hand-to-hand encounter with half a dozen enemy soldiers will leave the reader spellbound. It allows those who have never served in a war to gain an understanding of the cohesion that develops between soldiers who face death on a daily basis, and how they manage to overcome their fears through unit loyalty and support.

The book is not for the faint-hearted. Bellavia pulls no punches when he writes of his near-death experiences in Iraq. “I don’t have nightmares that I read other veterans are having,” he writes. “None of my old friends do either. I don’t dream about seven-foot insurgents chasing me down Iraqi streets. And yet I think about Iraq almost every day of my life. Almost every dream I have is about Iraq, but none of them are bad. There will constantly be regret, sorrow for those we lost, but never nightmares. I will always hate war, but will be forever proud of mine.”

Casualty Figures: How Five Men Survived the First World War by Michele Barrett, Verso, London, 2007, photos, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Casualty Figures: How Five Men Survived the First World War by Michele Barrett, Verso, London, 2007, photos, index, $24.95, hardcover.

“It is heartbreaking to watch a shell-shock case,” wrote World War I veteran Corporal Henry Gregory. “The terror is indescribable. The flesh on their faces shakes in fear, and their teeth continually chatter. Shell shock was brought about in many ways: loss of sleep, continually being under heavy shell fire, the torment of the lice, irregular meals, nerves always on end, and the thought always in the man’s mind that the next minute was going to be his last.”

The dead and wounded of any conflict are not the only casualties. Those who survive the carnage should also be included in that mournful number. And it some ways, their fate is much worse than their comrades who paid the supreme sacrifice on the battlefield. This book examines five British soldiers and how the effects of shell shock altered their lives after the war. Many soldiers could not escape the nightmares and horrors they had witnessed. No amount of training could have prepared them for the killing fields of France or Gallipoli.

Initially, senior officers dismissed shell shock as cowardice, and men were summarily executed for refusing to go back into combat. It was not until medical personnel began to closely examine the battle-induced mental illness that any significant change occurred in people’s attitudes toward the condition.

“The war to end all wars” was the first conflict to illicit this behavior in combat soldiers on a large scale. Whether it is called combat fatigue, post-traumatic stress disorder, or Gulf War illness, the symptoms are similar. And after all the hoopla at war’s end, the endless stream of patriotic parades and noble-sounding rhetoric spewed out by politicians on town greens across the country, it is the combat veteran who bears the brunt of the suffering—often in private.

Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and its Influence on World Events, Vol. II, 1946-2006 by Norman Polmar, Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2008, 548 pp., photos, maps, glossary, notes, index, $49.95, hardcover.

Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and its Influence on World Events, Vol. II, 1946-2006 by Norman Polmar, Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2008, 548 pp., photos, maps, glossary, notes, index, $49.95, hardcover.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese empire struck American forces at Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands. When it was over, hundreds of enemy aircraft had sunk or damaged numerous American vessels, including the ill-fated USS Arizona. All of this was accomplished by aircraft carriers that secretly made their way undetected to their destination. Fortunately for the Americans, their own carrier fleet was out to sea on that fateful day and would survive to defeat the Japanese Navy at the Battle of Midway a mere six months later.

The importance of a carrier fleet in today’s world cannot be overstressed. Their constant vigilance maintains our nation’s “forward presence” in combat zones and in assisting our allies with their fighting capabilities. Aircraft Carriers traces the lineage of the World War II-era carrier to become the supercarrier of today. The book has a multitude of photos depicting various models of ships and the wide assortment of aircraft that are launched from their decks. For the naval aficionado who cannot get enough of the history of the carrier, this coffee table-size book is indispensable.

The USS Flier: Death and Survival on a World War II Submarine by Michael Sturma, The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, 2008, 209 pp., notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The USS Flier: Death and Survival on a World War II Submarine by Michael Sturma, The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, 2008, 209 pp., notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

This is an amazing story of survival during wartime. What makes it so fascinating is that the survivors managed to escape a sinking submarine after it hit a mine in the Balabac Strait separating Borneo from the Philippines on August 12, 1944. Eight crew members, including the skipper, Lt. Cmdr. John Crowley, managed to swim from the sinking sub and eventually made it to land. They were picked up by Filipino guerrillas and rescued 18 days later.

Controversy still surrounds the incident. It seems that this was not the first such incident the Flier had endured while under Crowley’s command. Subsequently, he underwent two boards of inquiry before being exonerated and given another submarine command. He retired in March 1961.

But the tragic affair of the Flier also demonstrates exceptional courage and cooperation between American and Allied forces. Had it not been for the intrepid Filipinos and a small group of coast watchers, the crew would almost certainly have died of exhaustion and hunger or fallen into enemy hands. It is an incredible tale that was almost forgotten, but that Sturma has revived in this vivid account.

Mr. Gatling’s Terrible Marvel: The Gun That Changed Everything and the Misunderstood Genius Who Invented It by Julia Keller, Viking Books, New York, New York, 2008, 283 pp., notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Mr. Gatling’s Terrible Marvel: The Gun That Changed Everything and the Misunderstood Genius Who Invented It by Julia Keller, Viking Books, New York, New York, 2008, 283 pp., notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Perhaps no other invention altered warfare more than the Gatling gun. Invented by Dr. Richard J. Gatling, it was first introduced in 1862. President Abraham Lincoln was immediately enthralled by the new weapon. By using a hand crank, it could fire between 500 to 1,000 rounds per minute. Later, the inventor diverted some of the gas that propelled the rotating cluster barrels and even built in electric motors to turn them.

After the turn of the century, the Gatling gun became obsolete before making a surprising resurgence in the 1950s and 1960s. Mini-guns were installed on the old C-47 aircraft, known as “Spooky” or “Puff the Magic Dragon,” and they were used as close-air support in Vietnam. AC-119s and C-130 Spectre gunships used them as well. Each gun could fire 6,000 per minute and was a formidable weapon on the battlefield.

It was the original design, however, that brought fame to its inventor and helped propel the United States onto the world scene as a military force to be reckoned with. Julia Keller, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist on the Chicago Tribune, has written a marvelous book about the creation of the first modern machine gun and the gentleman who invented it—ironically—as a deterrent to war.

50 Aircraft That Changed the World by Ron Dick and Dan Patterson, Firefly Books, Buffalo, New York, 2007, 208 pp., photos, index, $39.95, hardcover.

50 Aircraft That Changed the World by Ron Dick and Dan Patterson, Firefly Books, Buffalo, New York, 2007, 208 pp., photos, index, $39.95, hardcover.

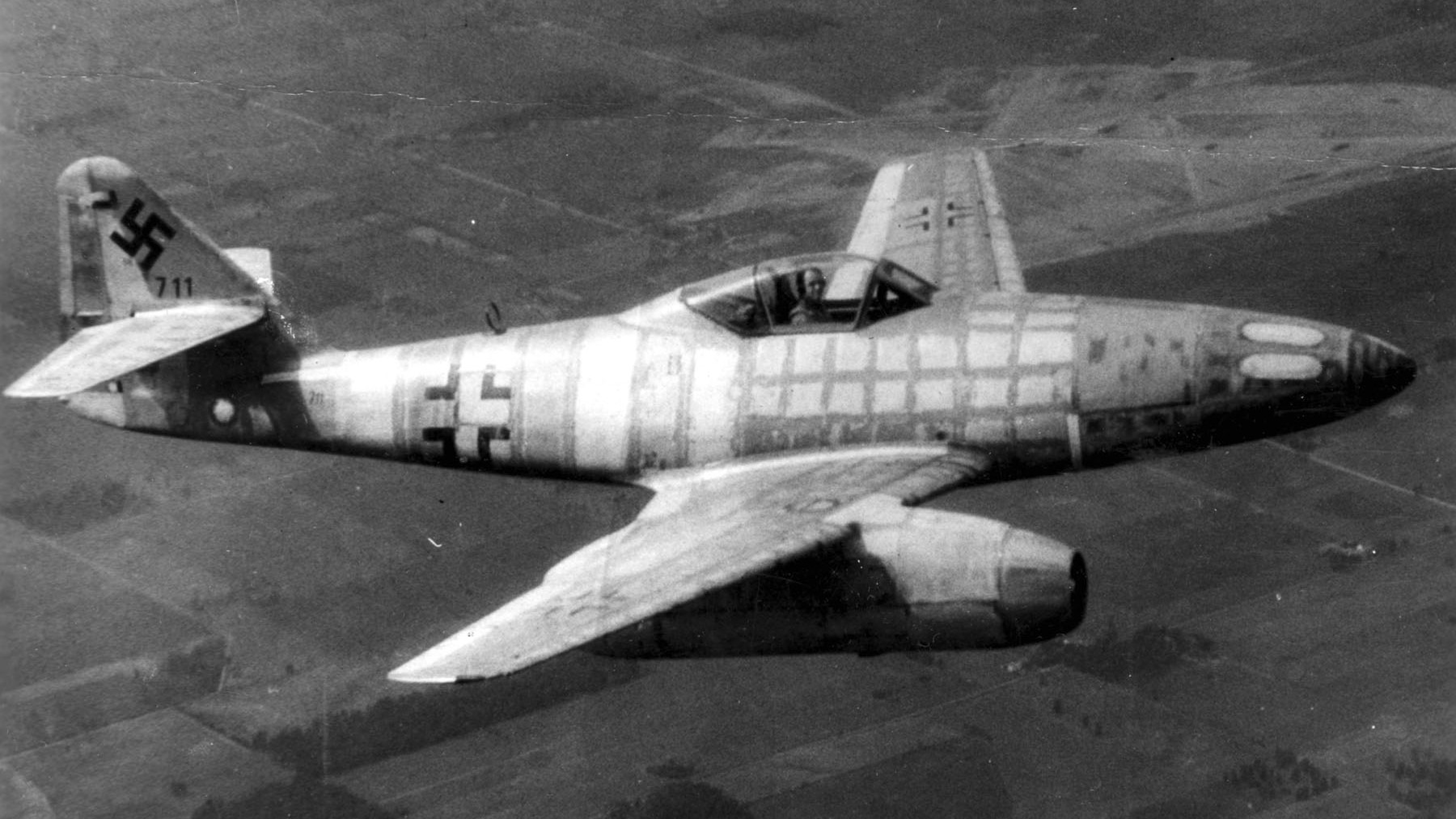

If you had to pick 50 aircraft that changed the world, which ones would they be? Authors Ron Dick and Dan Patterson have made their own choices, and the results are included in a coffee table book rich with archival and color photographs of the planes that they believe altered history.

Topping the list is the 1905 Wright Flyer III flown at Huffman Prarie, an 80-acre meadow near Dayton, Ohio. On October 5, 1905, Wilbur Wright flew 24 miles in 39.5 minutes, an astonishing feat in the world’s first practical flying machine.

Not all the planes selected by the authors are American-made. Credit is given to the Mitsubishi Zero A6M, a formidable fighter in its own right. Known as the Zero, the plane had a distinct advantage early in World War II because of its long-range capabilities. It was not until the United States Army Air Force introduced the Corsair and the Mustang in the Pacific that the Japanese Zero had a true competitor in the skies.

The new, innovative fighter jet for the 21st century is the F-35 Lightning II. In the opinion of the authors, it “represents a major advance in military aviation.” A high-tech electro-optical targeting system, thermal imaging system, lasers, pneumatic weapon delivery system, and lift-fan anti-icing system, are just a few of the reasons making the F-35 a state-of-the-art aircraft in air combat today.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments