By Lt. Col. Harold E. Raugh, Jr., Ph.D., U.S. Army (Ret.)

The United States has been called a country made by war. Its history has been influenced and shaped by pivotal land and sea battles.

To reinforce this theme, prominent Civil War and naval historian Craig L. Symonds has written Decision at Sea: Five Naval Battles that Shaped American History (Oxford University Press, New York, 2005, 378 p., illustrations, maps, notes, index,

$30.00 hardcover). In this well researched and elegantly written study, aimed at a general audience, Symonds dissects and analyzes five watershed naval battles. These reflect not only the changes in warfare but highlight how war is also a vehicle of social, cultural, and technological change.

The first engagement described is the Battle of Lake Erie, September 10, 1813, during the War of 1812. U.S. Navy Commodore Isaac Chauncey constructed a small fleet on the shores of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Chauncey delegated command on Lake Erie to Captain Oliver H. Perry, who was in charge of two brigs, six schooners, and a sloop. Perry sailed forth to meet an approaching British squadron on September 10. When his flagship was put out of action, he transferred to another vessel, and after breaking the British line, the American ships closed in and defeated the British. This solid victory secured the American claim to the Northwest Territory and enabled future expansion.

The Battle of Hampton Roads, March 8-9, 1862, pitted the U.S.S. Monitor (the “cheesebox on a raft”) against the Confederate ironclad Virginia (Merrimack). After four hours of pounding each other, the Virginia returned to Norfolk and the Monitor kept control of Hampton Roads. Even though this battle was inconclusive, it was significant as being the world’s first engagement between ironclad ships, ushering in “the age of machine warfare.”

The United States emerged as a nascent world power after achieving victory in the Spanish-American War of 1898. A decisive factor was the American naval defeat of the Spanish armada at the Battle of Manila Bay, May 1, 1898. Symonds considers this naval encounter “the nation’s first that involved the oceangoing steam and steel warships of what historians have labeled the ‘New Navy.’”

At the Battle of Midway, June 4-6, 1942, American ships and carrier-based aircraft achieved, assisted by knowledge of Japanese secret codes and the Japanese dispersal of its ships, a resounding victory over the Japanese fleet. All four Japanese aircraft carriers, and hundreds of planes, were destroyed; American losses paled in comparison. After this decisive naval victory, the psychologically scarred Japanese were on the defensive, and the Americans gained the initiative in the Pacific.

The last naval battle covered is the little-known Operation Praying Mantis in the Persian Gulf, April 18, 1988. After the U.S.S. Stark was struck by missiles in 1987, American strategic attention centered on the Persian Gulf. This was also the result of Cold War rivalry in the area, and because of America’s concern for its oil supply, it began re-flagging and escorting oil tankers in the Persian Gulf. After increased confrontations, on April 18, 1988, U.S. forces destroyed Iranian oil platforms, and in the ensuing battle, numerous Iranian gunboats were destroyed. This naval action demonstrated the precision of electronically integrated missile systems. It also, according to Symonds, “marked the emergence of the United States in its new role as the world’s policeman”—not necessarily a good thing.

This excellent book shows how key naval battles have influenced American history. Even more importantly, each of the battles described “provides insight into the essential features of naval combat and command at sea” and highlights the importance of the fighting spirit and the warrior ethos.

Recent and Recommended

The Intrepid Guerrillas of North Luzon, by Bernard Norling, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2005, 284 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $19.95 softcover.

After the fall of Bataan (April 9, 1942) and the surrender of Corregidor (May 6, 1942) in the Philippines, the majority of U.S. Army and Philippine Army soldiers serving in the Phillippines became prisoners of war. This interesting book focuses on the World War II activities of Troop C, 26th Cavalry Philippine Scouts, which was separated from its parent unit and decided to continue resistance against the Japanese. It was later expanded and became the guerrilla Cagayan-Apayao Forces (CAF) in two of the northernmost provinces of Luzon. Troop C, under the command of Captain Ralph Praeger, was thereafter active in hostilities against the Japanese. Ambushes, raids, and other combat patrols were conducted, and intelligence was relayed to higher headquarters.

The daily operations, trials, and tribulations of Troop C soldiers and their guerrilla counterparts, until Praeger’s capture on August 30, 1943 and the disintegration of the CAF, are chronicled in rich detail. The CAF contribution to the war effort was noteworthy and commendable. The Intrepid Guerrillas of North Luzon (in spite of concerns about sources and documentation) is important and timely in that it again brings attention to the diminishing group of stalwart American soldiers who refused to surrender at Bataan or Corregidor and their intrepid Filipino allies who for years harassed and fought the Japanese invaders until victory was achieved.

Chariot: From Chariot to Tank, The Astounding Rise and Fall of the World’s First War Machine, by Arthur Cottrell, Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, New York, 2005, 352 pp., illustrations, maps, notes and references, index, $29.95 hardcover.

Chariot: From Chariot to Tank, The Astounding Rise and Fall of the World’s First War Machine, by Arthur Cottrell, Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, New York, 2005, 352 pp., illustrations, maps, notes and references, index, $29.95 hardcover.

The invention of the chariot and its use as a war machine was instrumental in changing the dynamics of the battlefield from the ancient to the modern world. In this absorbing study, Arthur Cottrell, an expert on ancient civilizations, traces the development, rise, and fall of the chariot in Europe, West Asia, Egypt, India, and China. This volume begins with an examination of the role of the chariot in notable ancient battles. These include Kadesh (1274 bc), where the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II was surprised by some 3,500 Hittite charioteers and almost defeated; Megiddo (1460 bc), where 1,000 Egyptian chariots unexpectedly traversed a narrow pass and surprised the enemy Canaanites; and two battles in China (Chengpu, 632 bc, and Bi, 595 bc) where chariots played an important role. The development of the chariot, explains Cottrell, was dependent on three critical components: the spoked wheel, domesticated horse, and compound bow. These innovations are also assessed. In the penultimate chapter, “Survivals, Ritual, and Racing,” Cottrell narrates the later Roman practice of celebrating the “triumphal chariot,” chariots in funerals, and finally, the popularity of chariot racing, a la Ben Hur. Filled with anecdotal information and numerous illustrations, this fine book is interesting as well as entertaining to read.

The Devil’s Broker: Seeking Gold, God, and Glory in Fourteenth-Century Italy, by Frances Stonor Saunders, Fourth Estate, HarperCollins, New York, 2005, 396 pp., illustrations, maps, source notes, select bibliography, index, $25.95 hardcover.

The Devil’s Broker: Seeking Gold, God, and Glory in Fourteenth-Century Italy, by Frances Stonor Saunders, Fourth Estate, HarperCollins, New York, 2005, 396 pp., illustrations, maps, source notes, select bibliography, index, $25.95 hardcover.

Armed bands of avaricious freebooters ravaged and looted Europe during lulls in the calamitous Hundred Years’ War between England and France (1337-1453). One of the most prominent, successful, and ruthless of these mercenaries was the Englishman Sir John Hawkwood. In about 1360, Hawkwood formed his own company and moved from France southwards to the rich city-states of Italy. On the way, Hawkwood successfully extorted the pope and began a pattern of extracting money from principalities for protection. He fought for the highest bidder: at various times for or against Milan, Pisa, Florence, Naples, Padua, and the pope. In 1377, his force massacred some 6,000 inhabitants of the city of Cesena. Shortly thereafter, he entered the service of Florence and fought for it, in spite of bribes to switch allegiance, until his death in 1394. This chronicle of life and military activities of the once prominent and now little-known Hawkwood is nicely written; The book is fascinating and a pleasure to read.

The Trafalgar Companion, edited by Alexander Stilwell, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2005, 224p., illustrations, maps, endnotes, bibliography, index, $29.95 hardcover.

The Trafalgar Companion, edited by Alexander Stilwell, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2005, 224p., illustrations, maps, endnotes, bibliography, index, $29.95 hardcover.

The legacy of Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson and his fabled naval victory at Trafalgar on October 21, 1805, are essential components of the spirit and identity of the British people. In this perceptive anthology, prominent naval historians examine Nelson’s life and leadership and the significance of his success at Trafalgar, where he died at the hour of victory. After an introduction providing the political and military context and strategy of the Napoleonic Wars by John B. Hattendorf, Peter Padfield describes the governments and cultures of the British and French opponents. Edgar Vincent, in one of the book’s most interesting essays, assesses the physical and psychological Nelson and his “kaleidoscopic character.” In another chapter, Vincent studies “Nelson the Commander.” The French and Spanish perspective is provided by Admiral Remi Monaque, and other chapters describe naval tactics, Nelson’s flagship H.M.S. Victory, the Battle of Trafalgar, and the evolution of Nelson’s iconic reputation. Published to coincide with the 200th anniversary of Trafalgar, this interesting, profusely illustrated, and handsomely produced volume makes a valuable contribution to Nelson studies.

A Bearskin’s Crimea: Colonel Henry Percy, VC, and His Brother Officers, by Algernon Percy, Leo Cooper, Barnsley, UK, 2005, 238 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, references, bibliography, index, $36.95 hardcover.

A Bearskin’s Crimea: Colonel Henry Percy, VC, and His Brother Officers, by Algernon Percy, Leo Cooper, Barnsley, UK, 2005, 238 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, references, bibliography, index, $36.95 hardcover.

Henry Percy was an officer in the British Army’s Grenadier Guards who fought in all four major battles—Alma, Balaklava, Inkerman, and Sevastopol—of the Crimean War, 1854-1856. Percy, born into an aristocratic family in 1817 and commissioned into the bearskin-hat wearing Grenadier Guards in 1836, was a company commander when the Crimean War began. He was wounded at the Alma and demonstrated outstanding leadership and gallantry in action at the Battle of Inkerman, November 5, 1854. On that foggy morning, the Russians launched a major assault against the British. The Guards Brigade, including the Grenadiers, engaged the enemy in fierce hand-to-hand fighting at the Sandbag Battery. Percy and a number of other soldiers were cut

off and nearly surrounded. Even though wounded, Percy led the soldiers to safety and continued the fight. For his intrepidity, Percy received the newly instituted Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest decoration for bravery in action, and eventually retired a knighted lieutenant general. This book is woven around Percy’s voluminous correspondence, which highlights “the progress of the war, the failings of the generals, the sufferings of the men, the lack of supplies, the appalling medical arrangements,” and other factors that characterized the Crimean War. This is a highly readable, outstanding book.

Sheridan’s Lieutenants: Phil Sheridan, His Generals, and the Final Year of the Civil War, by David Coffey, Rowman & Litlefield, Lanham, MD, 2005, 168 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliographical essay, index, $22.95 hardcover.

Sheridan’s Lieutenants: Phil Sheridan, His Generals, and the Final Year of the Civil War, by David Coffey, Rowman & Litlefield, Lanham, MD, 2005, 168 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliographical essay, index, $22.95 hardcover.

Major General Philip Sheridan’s rise during the Civil War was nothing short of meteoric—from lieutenant in 1861 to major general in 1864. In April 1864, 33-year-old Sheridan emerged from relative obscurity, handpicked by General U.S. Grant, to command the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Sheridan gathered a group of courageous, innovative, and talented subordinates who assisted him in audaciously prosecuting the Union war effort. The Cavalry Corps was divided into three divisions. General ATA Torbert commanded the 1st Division, and its brigades were commanded by General GA Custer, Colonel TC Devin, and General Wesley Merritt. The 2nd Division was commanded by General D. McM. Gregg; General HE Davies and Colonel J. Irvin Gregg were its brigade commanders. General JH Wilson commanded the 3rd Division, with Colonels JB McIntosh and GH Chapman commanding brigades. More than an operational history, this book is about military leadership, focusing on Sheridan as mentor and his subordinate commanders as protégés. The dynamics of command and professional and personal relationships are assessed to ascertain their contributions to unit effectiveness and battlefield victory. Sheridan’s “martial brotherhood” dominated the U.S. Army until the turn of the century. This absorbing book on military leadership and cavalry operations leaves the reader yearning for even more.

More Damning than Slaughter: Desertion in the Confederate Army, by Mark A. Weitz, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2005, 346 pp., illustrations, maps, tables, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $49.95 hardcover.

According to Professor Mark A. Weitz of Gettysburg College, desertion was a problem that “plagued the Confederate military for most of the [Civil] war.” In this scholarly study, Weitz examines this phenomenon to ascertain reasons, patterns, and timing of military desertions and to determine its impact on the overall Confederate war effort. Official Confederate records admit to 103,400 military desertions, but these figures are problematic. Weitz looks at numerous state, unit, and hospital records, plus participant letters and memoirs, within the chronological framework of Confederate military operations. These strongly suggest many motives for desertion, including low and irregular pay, inadequate food and supplies, disease, poor medical care, the need to perform agricultural tasks on home farms, and weak discipline, especially early in the conflict. As the war progressed and ravaged the South, the soldiers’ concerns for their frequently destitute families overrode military necessity, unit allegiance, and loyalty to the Confederate States of America. Weitz concludes that desertion, along with other problems, “truly crippled the Confederate war effort and in the end hurt much more than slaughter.”

The Grand Old Man of Maine: Selected Letters of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, 1865-1914, edited by Jeremiah E. Goulka, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2004, 384 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $39.95 hardcover.

The Grand Old Man of Maine: Selected Letters of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, 1865-1914, edited by Jeremiah E. Goulka, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2004, 384 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $39.95 hardcover.

Colonel (later General) Joshua L. Chamberlain was, for most of the twentieth century, a relatively obscure and little known Civil War commander until he was thrust into the limelight in Michael Shaara’s 1975 novel The Killer Angels. Chamberlain commanded the 20th Maine Infantry, and by audaciously leading a bayonet assault at Little Round Top, probably saved the Union left flank at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. He was wounded six times, commanded a brigade, and emerged from the Civil War a veritable hero. This is a collection of Chamberlain’s post-war letters, from a period of his life little examined. Chamberlain served as governor of Maine (1866-1871), president of Bowdoin College (1871-1883), railroad executive, and surveyor of customs at Portland, Maine. Chamberlain’s fascinating, deftly edited, and voluminous correspondence reveals what a tremendous impact the Civil War had on him. His letters also show the importance of memory and commemoration of the Civil War, and the politics of veterans, pensions, and recognition, with “the theme of Victorian manhood and masculinity” intertwined throughout. This valuable collection of well-edited letters sheds light on the life and times of Chamberlain, Civil War hero and “the Grand Old Man of Maine.”

The Somme, by Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2005, 352 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00 hardcover.

The Somme, by Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2005, 352 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00 hardcover.

The Battle of the Somme during World War I has come to represent the futility of war and the incompetence of British generals. The bloodiest battle in British history, some 432,000—or about 3,600 per day—became casualties from July 1 to mid-November 1916. The battle kicked off on July 1, and the British suffered 60,000 casualties that one day while attacking well-established German defenses. In mid-July, a British night attack pierced the German second line, with cavalry riding into the gap. The horsemen, because other reinforcements were delayed, were mowed down by German machine guns. After an enemy counterattack, the offensive was reduced to a series of small but costly attacks that were called off in mid-November. Australian military historians Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson have mined official documents and private-paper repositories in England and Australia to reconstruct authoritatively relevant aspects of the higher direction of the war, theater leadership and decision-making, and the tactical execution of the offensive. Their considered conclusion is that the British civilian leadership played a large role in the conception and direction of the British battle, British fire support was inadequate, and Haig (British commander-in-chief) “performed badly” in command, failed to coordinate his armies, and “was in denial about the reality of warfare on the Western Front.”

Hostages to Fortune: Winston Churchill and the Loss of the Prince of Wales and Repulse, by Arthur Nicholson, Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill, UK, 2005, 224 pp., illustrations, maps, chapter endnotes, appendix, select bibliography, index, $34.95 hardcover.

Hostages to Fortune: Winston Churchill and the Loss of the Prince of Wales and Repulse, by Arthur Nicholson, Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill, UK, 2005, 224 pp., illustrations, maps, chapter endnotes, appendix, select bibliography, index, $34.95 hardcover.

As the Japanese continued to make bellicose moves in Southeast Asia in 1941, the British decided to send a powerful “yet unbalanced and vulnerable” naval task force to the region to deter further Japanese aggression. The main ships of Force Z, as it was called, were H.M.S. Prince of Wales (a 35,000-ton King George V class battleship) and H.M.S. Repulse (a 26,000-ton Renown class battlecruiser). After the Japanese landed troops in northern Malaya on December 8, 1941, these two ships and four destroyers steamed from Singapore to find and strike the enemy. After a fruitless search, Force Z, with no air cover, was attacked by a strong Japanese torpedo plane and high-level bomber force. Both heavy ships were hit several times and sent to the bottom. These were the first capital ships to be sunk by air attack while operating on the high seas. Their sinking further stunned a naval world reeling in the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack only a few days earlier. Author Arthur Nicholson has scrupulously researched primary source documents to examine the decisions behind the dispatch of Force Z to Singapore (including Churchill’s dominant role) and its conduct of operations at “the Battle off Malaya.” The result is a tightly argued and balanced portrayal of “a tale of momentous and difficult decisions, great and heroic men, powerful and graceful ships, [and] cruel twists of fate.”

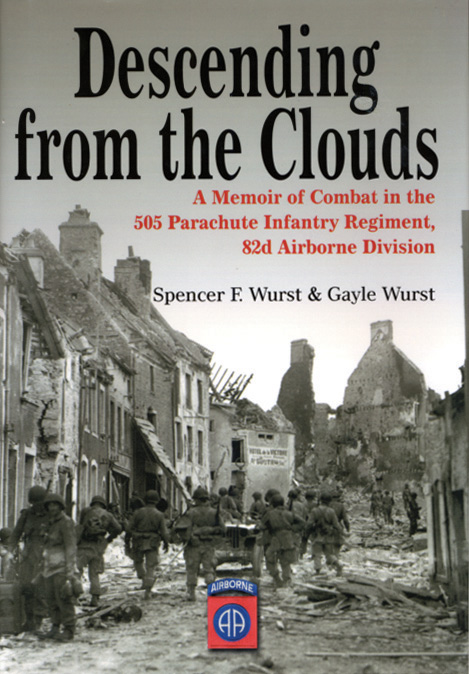

Descending from the Clouds: A Memoir of Combat in the 505 Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82d Airborne Division, by Spencer F. Wurst and Gayle Wurst, Casemate, Havertown, PA, 2005, 256 pp., illustrations, maps, $32.95 hardcover.

Descending from the Clouds: A Memoir of Combat in the 505 Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82d Airborne Division, by Spencer F. Wurst and Gayle Wurst, Casemate, Havertown, PA, 2005, 256 pp., illustrations, maps, $32.95 hardcover.

“The first time I went up in a plane,” writes Spencer F. Wurst in this interesting memoir, “I jumped out of it.” Wurst was a soldier in the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, in World War II. He jumped out of airplanes many more times and participated in three of his regiment’s four combat jumps. Lying about his age, 15-year-old Wurst enlisted as a private in the Pennsylvania Army National Guard in 1940, and his unit was federalized in February 1941. He requested a transfer and attended Parachute School at Ft. Benning, Georgia, in 1942. Assigned to the 505th, Wurst made his first combat jump at Salerno in September 1943 and fought in Italy. He made the chaotic “big jump” into Ste. Mere-Eglise on D-Day and was wounded during the vicious hedgerow fighting in Normandy. He jumped into Holland during the ill-fated Operation Market Garden, received the Silver Star for his gallantry in action, and later fought in the Battle of the Bulge. In this fascinating wartime memoir, Wurst shows great attention to detail as well as humanity and sensitivity. His keen observations of training and small unit combat in the fabled 82nd Airborne Division make a significant contribution to World War II historiography.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments