By Kevin M. Hymel

“Awe c’mon, Mom,” Cecil Petty told his emotional mother before leaving Homer, Illinois, in February 1941. “Who knows, I might be a hero.” But being a hero was probably the furthest thought from Petty’s mind more than a year later as he sat in the cockpit of his C-47 Skytrain, the Lana Turner, as Japanese shells exploded around him.

On October 20, 1942, the 26-year-old U.S. Army Air Forces lieutenant was trying to take off from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. His aircraft held 18 wounded Marines, some of whom had been fighting the Japanese for two months and were suffering injuries, jungle infections, and mental distress from constant combat. Petty’s mission was to fly them to an Army hospital in the New Herbrides.

Petty, his copilot, Lieutenant Eugene Ecklund, and their two crewmates—a crew chief and a radio operator—were part of the Army Air Forces 13th Troop Carrier Squadron, “The Thirsty 13th,” hauling ammunition and fuel to the Marines on the island and bringing out the wounded. They were helping the Marines defending Henderson Field from the Japanese. For this flight, they were joined by two U.S. Navy navigators and a pharmacist’s mate. The shelling they endured was part of a Japanese attempt to soften up the Americans before attacking the airfield.

Japanese artillery salvos delayed planes from getting into the air. When the shells started exploding around the airfield, ground crews offloaded the wounded, and everyone else dove for foxholes. Among the Japanese artillery pieces was an American 155mm cannon they had captured in the Philippines and were now using against its former owners. When the shelling stopped, the wounded were loaded back on board; then the shelling resumed. Again, the wounded were offloaded, and everyone headed for foxholes. By the time the wounded were loaded a third time, the sun was setting. To help Petty and Ecklund see well enough to take off, three Marines stood in large shell holes on the runway, pointing flashlights at the plane so Petty could weave around them.

No shells came, so Petty started up the aircraft and headed down the runway, taking off into the darkening sky. But the Lana Turner never arrived in the New Hebrides. The next day, the squadron’s operations center at Plaine des Gaiaccs (Plain of Gaiac Trees) on New Caledonia listed the plane as missing in action. Speculation ran rampant. Men wondered if the plane had been shot down, had engine trouble, or simply crashed into the sea. The more optimistic men speculated Petty had landed on an island and been saved by friendly natives.

Searches commenced immediately. Although busy with their mission for the Marines, crews searched the seas for any sign of the Lana Turner. They looked for wreckage, rafts, and parachutes, anything that might provide a clue to the plane’s fate. They found nothing. It was as if the Coral Sea had swallowed Petty’s aircraft whole.

As the days passed, fellow Thirsty 13th pilots flew their missions to Guadalcanal and the New Hebrides, hoping that Petty and his plane would eventually be spotted. By the seventh day, some of the officers proposed closing the case and declaring the crew lost. It had simply been too long. “No! No!” shouted one of Petty’s friends. “Petty will make it,” he argued. “Petty will make it.”

At daybreak on the eighth day, more than 300 miles away at Nouméa, New Caledonia, a radioman on a Navy ship, the SS Lurline, picked up a faint signal from a portable emergency transmitter as the ship pulled into port. The ship had just passed through an electrical storm, and the air was clear for long-distance transmissions. The captain passed it to the naval commander ashore, who relayed it around the area. Could it be Petty’s plane, or were the Japanese using a captured transmitter to lure the Americans into a trap? The Navy dispatched a destroyer, the USS Barton, to the scene.

Back at Plaine des Gaiacs, the men in the headquarters had their doubts, but the men on the flight line had none. Lieutenant Phil Remaklus got orders to fly out to the signal. When he reached his C-47 he found a crowd of men, all wanting to go along. He offered a sergeant who had qualified as a parachutist the opportunity to make the trip, but the sergeant had night duties so he begged off.

On the runway, men prepared food to be dropped to the survivors. They stuffed Spam sandwiches into three blue barracks bags, and one man added a bottle of Hennessy Cognac. They wrapped everything up in a life raft’s plastic cover, then wrapped the whole thing in the life raft. They were attaching the container to a parachute when Remaklus told them to stop. It would drift too much, he told them. One of the squadron members later complained that Spam sandwiches made for a terrible first meal. “I would have wanted to shoot the supply plane for dropping that,” he said.

Remaklus took off, flew north to the coordinates, and reached the designated spot after flying for less than an hour. To his surprise and amazement, he saw a downed C-47 resting on a submerged coral reef. Atop the plane stood men waving frantically. Remaklus circled the stricken plane and dropped his supplies. Below, one of the men jumped off the plane, swam over to the package, and retrieved it.

Remaklus radioed in his find. Soon, the Navy dispatched three Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats to rescue the crew but kept the Bartonsteaming toward the area. The ordeal had ended, but how had these men flown so far off course? How had they ended up on a coral reef, and how had they survived for eight days?

Eight days earlier, after Petty had lifted off from Henderson Field and flown for about an hour, a lightning bolt hit the Lana Turner, knocking out the radio. The crew chief reported the situation to Petty, adding that he was having trouble with the voltage regulator system. The plane’s electrical power dwindled. Worse, the radio compass could not locate the New Hebrides’ radio beacon. (It was later discovered that someone on the island had forgotten to refuel the electric generator that powered the beacon.)

Soon the plane lost electrical power, leaving her dark. Petty and Ecklund found themselves flying blind above the vast sea. The Lana Turner was supposed to arrive in the New Hebrides around midnight, but the hour came and passed, and there was still no island. The two inexperienced navigators took an hour to calculate their position using celestial navigation. They could only tell where they had been, not where they presently were.

Leaving Ecklund at the controls, Petty made his way to the rear of the plane, careful not to step on the wounded. When he came across a Marine lieutenant colonel, he introduced himself, shook hands with the officer, and whispered to him that they were lost. Marine Lt. Col. Randolph McCall was furious. He had endured fighting on the island for the last two months until an infected leg sent him to the hospital. He had tried to fly out on a Marine aircraft but was accidentally loaded onto Petty’s in the confusion and darkness after the Japanese shelling. In harsh language, he told Petty he did not trust Army pilots and that his navigators were terrible. Petty just smiled and told McCall the navigators were Navy men.

Petty then announced the situation to everyone. Some prayed, others hoped, and some shook with worry. As the plane droned on through the night, the men grew dead silent. The only sound was the breathing of the wounded.

Fuel ran low. Every time the fuel light blinked on (the one source of power still working in the aircraft), Petty and Ecklund switched to auxiliary tanks and back to regular tanks. Petty throttled back on the plane’s engines to save fuel and pointed the plane in whichever direction his navigators recommended. In the predawn hours, Petty chased after several islands, only to discover they were merely cloud shadows.

Over one supposed island, Ecklund noticed there were no clouds above it. It was not a shadow, but it was not an island. It was a coral reef. Petty pointed his plane toward the light-colored water and leveled off.

Just then one of the Navy navigators looked out his right window and saw the engine sputter and stop. When he told everyone about the reef just ahead, they sang out with cheers and thank-yous to God. Then the other engine cut out over the reef. Petty and Ecklund strapped on their helmets, lowered the plane’s flaps, and turned the craft into the wind as they descended closer and closer to the water. They reduced speed to 60 miles per hour as the tail touched the sea.

The Lana Turner hit the water with an ear-splitting crash, then skipped along the waves until slowing to a stop, bobbing in the water. It had reached the coral reef. The Navy corpsman cracked two ribs in the rough landing. Water filled the plane, reaching a depth of three feet, but at least it landed atop the reef. The wounded Marines checked their injuries. Fortunately, the landing produced only a few bumps and scrapes. They started asking each other their names, units, homes, and when they joined the Corps. Collectively, they recited the Lord’s Prayer.

Some of the men secured the plane’s tail wheel to the reef using the plane’s static line. To sink the plane onto the reef, the crew used machetes to punch holes in the wings. They also took off the fuel tanks’ caps and filled the tanks with water. It worked. The plane settled on the coral surface with its left wing sticking three feet above the waterline. To make themselves more visible to planes, the men draped a parachute over the Lana Turner’s tail.

The crew helped some of the wounded onto the top of the fuselage, laying them on tarps, life rafts, and seat cushions, which made sitting more comfortable. The delirious malaria patients remained in the cabin hanging from rigged hammocks made from parachutes to keep them out of the water.

Petty and Ecklund handed out food, consisting of C- and K-rations. Everyone was allowed one meal a day. They also rationed the plane’s three-gallon water supply. Each man would get two ounces twice a day. Through it all, Petty kept repeating the Lord’s Prayer. Lt. Col. McCall outranked Petty, but when he saw the job Petty was doing he decided to let the lieutenant stay in command.

The plane’s radio operator immediately started using a hand-cranked emergency portable radio transmitter with an antenna—known as a Gibson Girl—to send out an SOS signal. The radio had both a balloon and kite to elevate the antenna, so the operator stuck the deflated balloon onto one end of a long tube and stuck the tube’s other end into the water. The hydrogen in the water inflated the balloon and gave it buoyancy. The balloon, with antenna attached, rose over the plane as the men watched. Suddenly, it burst, and the antenna dropped out of the sky. The men had a second balloon but decided to save it for an emergency. Instead, they attached the antenna to the kite and flew it overhead. Everyone took turns transmitting their location every 15 to 30 minutes. Unfortunately, the transmitter was set to commercial ship, not military, frequency.

The navigators took sun shots and discovered they were 300 miles off course. They had landed on French Reef, some 40 miles northwest of Art Island and another 40 miles from New Caledonia. They realized they were too far from the regular air and sea lanes for anyone to pick up their limited transmissions.

In the course of the day, one man managed to shoot a fish, which McCall cut into small pieces for everyone. Around 4 pm, the men saw a plane flying well to the west. They fired a flare and tried using a mirror to attract its attention, but the effort failed.

By the second day the men had exhausted the food supply, except for some chocolate D-Bars and canned tomato juice. Occasional rain squalls staved off dehydration. While the wounded never asked for more water than was rationed, as the days passed they tried to bolster their spirits by talking about all the steaks and pies they would enjoy when they got home. It pained Ecklund to hear such talk.

Most of the men spent their nights sleeping inside the plane and going topside onto the fuselage during the day. None went onto the wings. McCall spent his time sitting in Petty’s seat, keeping his infected leg propped up on the control panel to ensure it stayed dry. Sitting next to him was Major A.J. Narum, who shared his pocket Bible. McCall prayed away his fears and asked God to help him and all the men onboard. He also kept his service pistol hanging on the headrest in case anyone went crazy. “I knew that in time all of us would,” McCall later wrote, “but I hoped I would not be the first, because I wanted to be able to take charge as the men would expect me to.”

One day stretched into another. Petty constantly checked the injured and the transmitter. He also distributed liquids. All the while, the Lord’s Prayer played in his head. Oddly enough, it was not in his voice, but the voice of Marjorie Hartenblower, a woman who sang at his church back home. On the fourth day, Petty had done all he could to take care of everyone and keep up their spirits. For the first time, he laid down and slept.

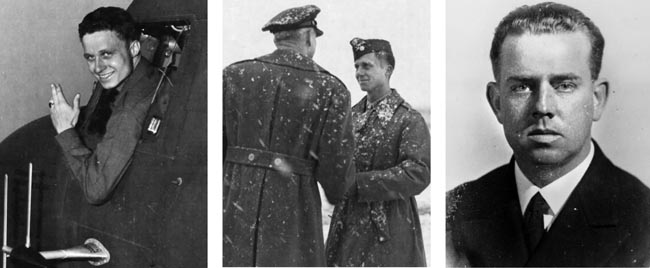

D-Day over Normandy with the 92nd Troop Carrier Squadron and survive the war a hero. RIGHT: Navy Lt. Cmdr. Douglas H. Fox died two weeks after his rescue of the Lana Turner and three PBYs when two enemy torpedoes sank the USS Barton in the First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal.

Despite the dangerous situation, the men enjoyed the peacefulness, particularly the sunrises, sunsets, and the starry nights. “It was beautiful,” recalled one of the navigators. “I always thought we were going to get rescued.”

On the fifth night a storm blew across the reef. Rain poured down, and waves crashed against the plane’s tail. “We were sure glad that C-47 was built better than it had to be,” explained Petty, “because it really withstood a pounding.” The men took advantage of the situation by collecting rainwater on ponchos and draining it into helmets, doubling their ration for the next two days.

Desperate for rescue, one of the two navigators recommended using a lifeboat to look for help. The officers talked it over and agreed it was worth a try. They gave Petty and his two-man crew half the water supply and helped them rig a small parachute sail. Once they were ready, they headed out for New Caledonia. With the winds and current against them, they had to paddle.

After hours of arduous paddling, the crew of three reached another reef about 15 miles out, yet they never lost sight of the Lana Turner, “even fifteen miles away and at night,” explained the navigator. When a seagull landed on the raft, the navigator grabbed it by its legs and killed it. The men also caught some fish. But the adventure was short lived. Late that night, strong winds buffeted the raft and drove it back in the direction of the aircraft.

By the next morning, the whole group was together again with little to show for their efforts. The men on the Lana Turner were not angry about the water supply situation since they knew Petty’s crew needed it to keep hydrated while paddling. The next night it rained lightly for about a half hour. The men caught water in their helmets, replenishing the water supply.

When the skies cleared after the rain on the eighth day, McCall decided it was a good time to try again to send a message on the Gibson Girl, reasoning that the atmosphere would be clear after a rain. Instead of the usual SOS, he sent a message giving the plane’s nautical location and that 25 men were getting hungry and needed aid. The radio operator sent the message every few minutes for an hour; others sent the message every hour for the rest of the day.

That afternoon the men spotted Lieutenant Phil Remaklus’s C-47 as it closed on their location and flew over them. They cheered and pounded on their craft. Petty was inside the airplane when he heard the commotion. He ran topside to see everyone pointing south. Just then Remaklus flew back over and tipped his wing in greeting. He circled and dropped food, water, and blankets. Petty dove into the water, swam to the supplies, and brought them back.

The men celebrated their pending rescue two ways: McCall led the men in the Lord’s Prayer, and the men found the bottle of Hennessy. By diluting the drink with water, they were able to make enough for everyone. The simple shot got the men drunk. Their dehydrated bodies quickly succumbed to the cognac’s effects. “I’ve never had so much fun in my life,” recalled McCall. The buzz only lasted 30 minutes, and then the men returned to their sober state.

Two planes, a C-47 and an Australian Air Corps Lockheed Hudson bomber, followed Remaklus. Both dropped more supplies. The men wolfed down their new meals and just as quickly threw them back up. Their bodies could not handle the richness after a weeklong liquid diet. They used the remaining food to make soup. By igniting deicing fluid in a dye marker can wrapped in insulation asbestos, they created a stove. To cook over it, they mixed navy beans, tomato juice, and other ingredients into their rain-catching, five-gallon aluminum can. Once heated, the men could digest the simple soup.

The next day, three PBY flying boats appeared in the sky, circled overhead, and splashed to a landing in 10-foot swells. They taxied near the Lana Turner but could not get onto the reef. They then pitched out life rafts with two-man crews, who paddled through the rough surf. The first raft took on six survivors, including McCall, while the other two loaded the rest. As the rescuers paddled back to their planes, rough waters knocked the men off their rafts, but they quickly climbed back on board. High winds scattered the rafts, while the first raft kept getting thrown back by the reef’s surf. Seeing the survivors’ dilemma, one of the PBY’s crew climbed onto the wings and threw lines to the first raft, but they fell short.

While the other rafts reached the other two PBYs, the first PBY turned on its engines and headed toward the stuck raft. The plane ran up on the reef, crushing its hull in the process. The survivors boarded, but to keep the plane balanced they had to climb onto the wings. That night, the skies opened up, drenching the men on the wings as 10-foot waves rocked the PBY. The crew remained inside the plane, some standing in waist-deep water.

The other two PBYs faired only slightly better. Since both had lost rivets during the rocky landings and the rough seas, their crews did not want to risk a takeoff. They radioed for a ship pick-up and spent the night bobbing in the sea, drifting west in enemy-patrolled waters.

The next morning, the destroyer Barton, under Lt. Cmdr. Douglas H. Fox, arrived near the reef. The destroyer was already loaded down with 235 survivors from the aircraft carrier Hornet, which had been sunk two days earlier. Knowing that the reef was too shallow to risk his ship, Fox ordered two whaleboats to retrieve the reef-bound PBY. The two boats were quickly dropped into the water, but the first boat’s engine failed, leaving the second boat to go in alone. As it approached the reef, the boat’s officer heaved a line to the men, but it too fell short. He tried again and again without any success. Finally, an ensign took the line and swam through the reef to the PBY.

The whaleboat now had a secure line connecting it to the stranded PBY. The men would have to sit in a small raft and pull themselves along the line to the whaleboat. McCall, as the senior officer on board, went first. He climbed into a raft and hauled himself hand over hand along the 200-foot line to the whaleboat, no easy task in the heavy swells. “It seemed to me that it took a week to cover the distance,” McCall remembered. Exhausted, gagging on salt water, and with his eyes burning, McCall reached the whaleboat, where the crew hauled him aboard and offered him alcohol-laced coffee, which he happily accepted. “It was black, hot, and wonderful.” Just then the line snapped, delaying the rescue yet again.

Its engine repaired, the second whaleboat arrived, armed with a throwing gun. Its bowman fired two lines at the remaining men. Both missed. Then the coxswain maneuvered the boat atop a 10-foot wave. When the craft crested, the coxswain turned it sharply, and the bowman fired his last line. It landed close to the PBY, and the men hauled it in. Since most of the survivors were too weak to pull themselves, a single sailor in a raft made repeated trips to the PBY and ferried survivors from the reef to the whaleboat.

Once everyone was aboard, the whaleboats headed to the Barton, where the ship’s crew had dropped a net over the side. Sailors assisted the men onto the deck. Fox put McCall in his cabin, where he listened to the Marine tell his saga of the last nine days. The Barton steamed to the other PBYs, which by now had drifted some 75 miles to the west.

By the time the Barton reached the PBYs, the sun was setting. The commander of one PBY offered to take off the next morning if the Barton would stand by, adding that he had enough gas to travel 300 miles. When Fox explained the next fueling station was more than 300 miles away, the commander and everyone else aboard abandoned the PBY. Despite the surging seas, everyone transferred out of the PBY without incident.

The last PBY’s commander did not argue to take off. His plane had popped too many rivets, so the Barton’s crew threw a line to the plane’s crew and pulled it alongside the quarterdeck. One man climbed aboard before rough seas pushed the plane toward the ship’s stern. The last 10 survivors, including Petty, left the PBY and piled onto an upside down, five-man raft. To signal the ship in the darkness, a PBY crewman climbed back into his aircraft to retrieve a flashlight. Just then a wave smashed the PBY into the ship, ripping a hole in the PBY’s nose and tearing the line. The men clinging to the raft looked on in horror as the plane drifted away and sank nose first into the dark sea.

Fox churned the Barton to circle but could not turn on its searchlights, lest it attract Japanese submarines. As the ship closed the loop, a small light pierced the underwater darkness. Then the PBY crewman broke the surface right next to the upturned raft, holding the retrieved flashlight. When the PBY went down, he had swum down 15 feet to the hole in the craft’s nose, popped through, and surfaced underneath the life raft. Holding his breath again, he had pushed himself down and surfaced in the open air.

The Barton came around too far from the survivors, so Fox had it try again, but this time it was too fast. On the third pass, the ship came in dead slow, and a crewman tossed a line to the men on the raft. Once they caught it, the crewmen walked it back to the cargo net. “We got drenched as the swells came in,” reported Petty, “but we all made it up the side of the ship.”

Fox cut his engines to pick up all the men he could. After about a half hour, all but one of the men were accounted for, but with the Japanese lurking anywhere and everywhere, he knew he was a perfect target dead in the water. One of the floating PBY crewmen had been broadcasting his location on an open channel before Fox came to the rescue. “There is no doubt in the writer’s mind,” Fox later wrote, “that their position was known to the enemy.”

After conferring with McCall, who agreed with his decision, Fox started his engines and sailed away. Fortunately, the next morning’s head count came up complete. The missing man had mixed in with theHornetsurvivors.

Before the Barton steamed into Nouméa’s harbor, Fox ordered a broom taped to its mast, signaling a clean sweep—they had rescued everyone. The wounded were loaded onto the SS Lurline, the ship that had first heard the Lana Turner’s distress signal. Some of the psychoneurotic cases actually seemed better after their ordeal. Eight days of peaceful recovery after the shock of their crash had calmed them. By the time they reached Nouméa, according to Petty, “You couldn’t tell the difference between them and the rest of us.”

The Lana Turner’s crew got one last surprise as they headed down the Barton’s gangplank: some of the 13th Troop Carrier Squadron’s men were waiting on the dock to greet their lost friends. Both Petty and Ecklund returned to the squadron and continued flying. The crew of the Barton was not as fortunate. Only 14 days after the rescue, she was sunk by two enemy torpedoes during the First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. Only 42 men survived. Fox was not among them.

Eight months after their ordeal, Petty and Ecklund earned the right to head back to the United States on July 4, 1943. They had completed their mission. They had flown supplies into Guadalcanal and flown the wounded out. More importantly, they survived a rare ditching in the Coral Sea, lived to tell about it, and had not lost a single man during the ordeal.

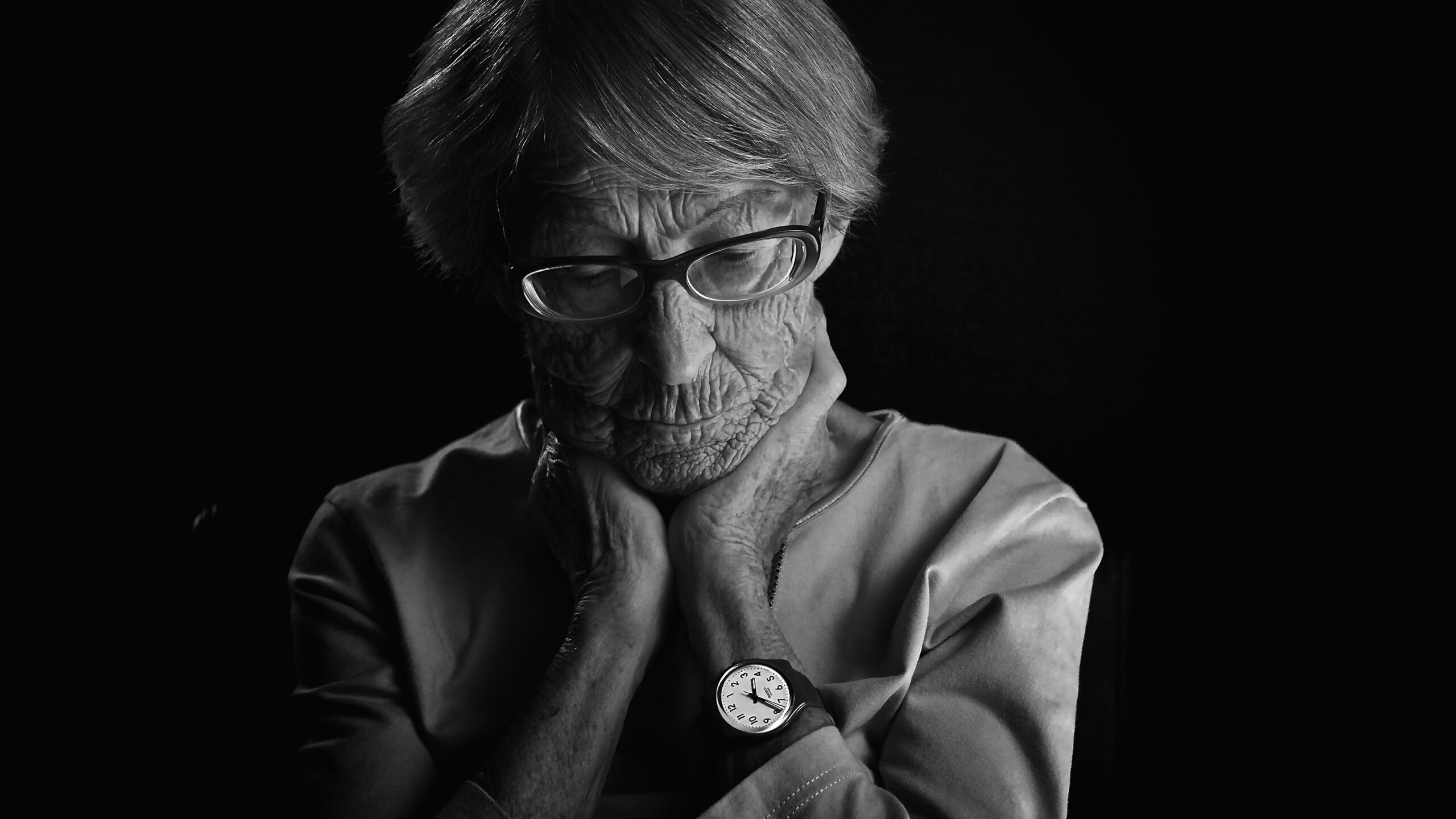

Cecil Petty went on to fly C-47s in the European Theater and survived the war. He never forgot Marjorie Hartenblower’s voice singing the Lord’s Prayer during his ordeal. After the war, he married her. Also, when he got home, his mother could call her son a hero.

Frequent contributor Kevin M. Hymel is a historian for the U.S. Air Force Medical Service History Office and a historian/tour guide for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours. This article was written from firsthand accounts and interviews in the book The Thirsty 13th: The U.S. Army Air Forces 13th Troop Carrier Squadron 1940-1945 by Seth P. Washburne.