By William E. Welsh

The German paratroopers marched the captured Canadian officer through the dark forest to the damp underground bunker that served as their platoon headquarters. It was the great misfortune of Lieutenant S.W. Nichols of the Canadian Black Watch to be nabbed inside the Reichswald Forest in the first week of February 1945, while leading a patrol to gather information on enemy dispositions.

Once inside the damp shelter, the cocky paratroopers introduced themselves to the young officer as members of Hitler’s “Green Devils.” The nickname was derived in part from the forest camouflage color of their uniforms and also from their menacing demeanor as elite troops of the Third Reich. It was an encounter that would remain seared on the young officer’s mind for the rest of his days.

Hustled off to the nearby fortress town of Kleve, Nichols was turned over to the Gestapo and subjected to a preliminary interrogation. In a lax moment afterward, Nichols slipped away from his captors and sneaked through the ruins of the recently bombed town until he was able to reenter the forest. For the next three days, he worked his way west, hiding in unoccupied trenches and dark patches of wood as he traveled nine miles back to friendly lines. Once back among the safety of his unit, Nichols told his superiors that the forest was inhabited by men who fancied themselves as Satan’s accomplices.

At the time of Nichols’s capture, the Allies had closed to within 25 miles of the Rhine River. Although German units that had participated in Hitler’s ill-fated offensive in the Ardennes Forest in December had managed to effect an orderly withdrawal in mid-January, they knew without a doubt that it was only a matter of time before the Allies reclaimed the offensive.

The question in the minds of German commanders up and down the 600-mile front that stretched from the North Sea to Switzerland was where the Allies would make their next major thrust. Unlike the upper reaches of the Rhine, where strong fortifications were nestled in rough terrain, the lower Rhine flowed through flat, open plains that offered the Allies the possibility of a rapid breakout into the German heartland. However, such an assault would require defeating a large number of crack paratroop and panzer units that had survived the Battle of the Bulge.

These troops were bundled into Army Group H, under the command Col. Gen. Johann Blaskowitz. Two corps belonged to the Twenty-fifth Army stationed in northern Holland, while three corps of the First Parachute Army protected the northern Rhineland. The latter had the added advantage of manning the northernmost section of Hitler’s West Wall, also known as the Siegfried Line. While Blaskowitz believed the Allies would make their main thrust across the Roer River on the southern end of his line, others such as First Parachute Army commander General Albert Schlemm fully expected the Allies to try to outflank the Siegfried Line with a quick thrust through the Reichswald.

In preparation for such an attack, Schlemm held his best divisions well back from the front so that they could respond rapidly to any penetration of his line. On the front line at the western edge of the Reichswald he placed the 84th Infantry Division under General Heinz Fiebig to absorb the shock of the initial attack. A reconstituted unit, the 84th Division comprised old and sick men recently pushed into service. Rethinking his initial strategy, Schlemm ordered three battalions of paratroopers into the forest to strengthen the resolve of the hapless recruits.

The Germans had begun construction of the West Wall in 1938 to protect Germany’s frontier with France from invasion. In subsequent years, the fortified line was extended the entire length of the French-German border and eventually as far north as Kleve. In the north, the barrier protected the highly vulnerable Rhineland, that part of Germany which lay on the west bank of the Rhine. The Allies, who failed to punch across the lower Rhine in Holland during Operation Market-Garden in September 1944, next turned their attention to gaining access to potential crossing points in a pincer attack on the northern end of the Siegfried Line.

For the coming offensive, Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight Eisenhower once again would entrust overall command of the campaign to British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, a move that dismayed Montgomery’s American counterparts. Despite the failure of Market-Garden, Montgomery hounded Eisenhower to provide him with sufficient forces to ensure a successful thrust into northern Germany.

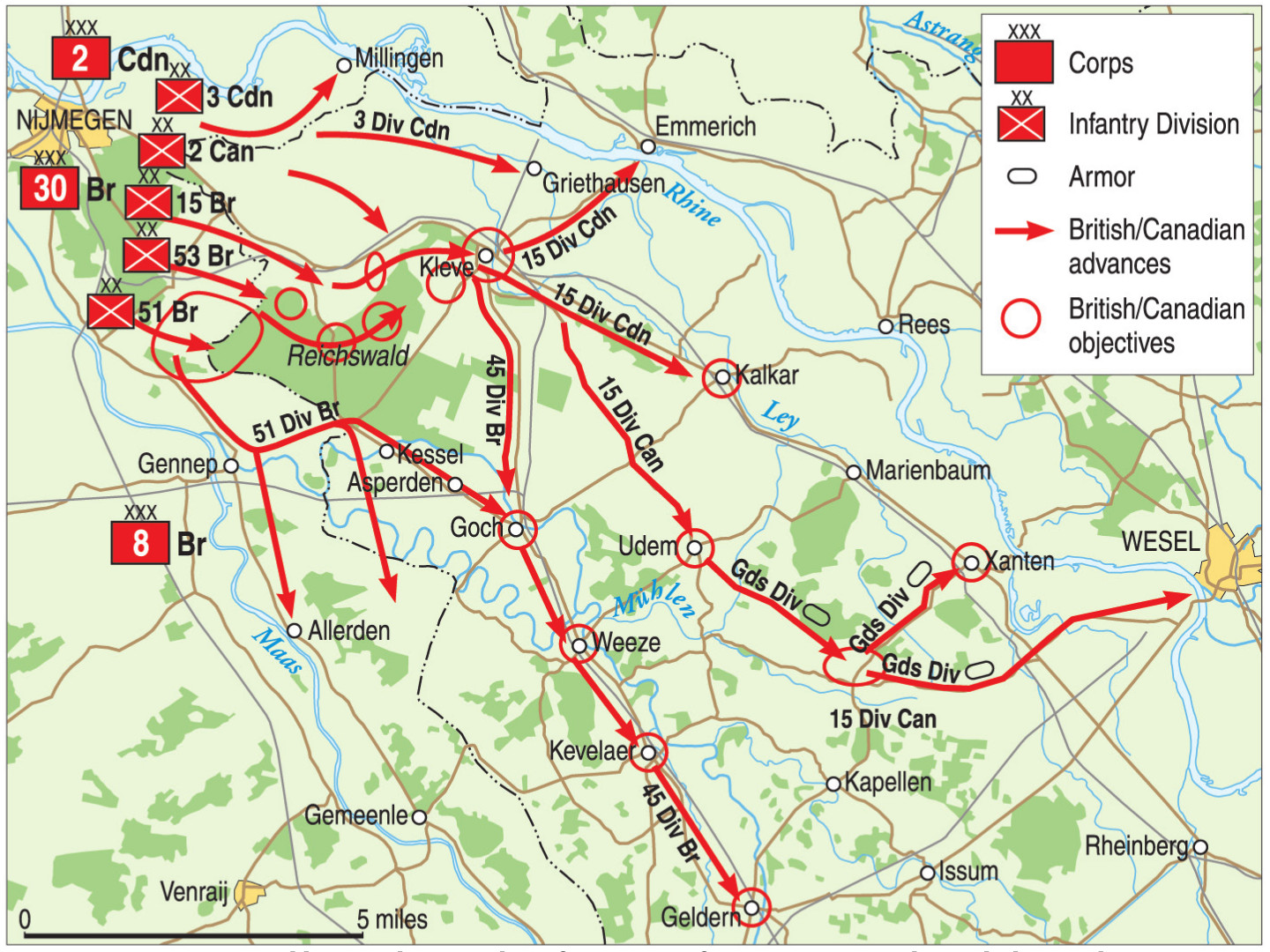

Montgomery’s single-thrust strategy conflicted with Eisenhower’s broad-front strategy, implemented in the wake of Market-Garden, by which the Allies would push forward slowly but steadily along the entire Western Front until a breakthrough was achieved. To indulge Montgomery, Eisenhower agreed to reinforce his Twenty-first Army Group so that the field marshal could exploit a bridgehead over the Maas River that the Allies retained following Market-Garden. The strategy that Eisenhower and Montgomery hashed out involved launching a two-pronged attack that would clear the northern Rhineland of German forces. To do this, the First Canadian Army, under General Harry Crerar, would strike east from Nijmegen, while Lt. Gen. William Simpson’s 9th U.S. Army, detached from General Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group and placed under Montgomery’s command for the campaign, would cross the Roer River and drive north to link up with the First Canadian Army. Crerar was ordered to launch his attack, designated Operation Veritable, on February 8, 1945, and Simpson was instructed to start his attack, called Operation Grenade, two days later.

The offensive, first conceived in October 1944, was postponed and revised as many as five times before it was finally launched. Limited successes on other parts of the front, coupled with the German surprise attack through the Ardennes, forced Eisenhower to rethink his broad-front strategy. One serious flaw in the strategy of the upcoming campaign was the difficulty that Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’s 1st U.S. Army, to Simpson’s immediate south, was having in its attempt to capture the seven dams that controlled the Roer River. Until these dams were in Allied hands, the Germans might flood the Roer behind Simpson, cutting his supply line. In the weeks following the Ardennes campaign, Eisenhower ordered Bradley, Hodges’s superior, to ensure that the dams were captured before the two offensives began. As events would show, the Germans held the upper hand in the matter of the dams.

The objectives of Crerar’s First Canadian Army for Veritable were to smash through the northern section of the Siegfried Line, capture or destroy together with Simpson’s 9th Army all German forces in the northern Rhineland, and secure points for possible Rhine crossings. Despite its name, the First Canadian Army contained a large number of British units. Crerar entrusted the initial assault to Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks, who commanded British XXX Corps, and put seven of the eight divisions from the 1st Canadian Army under Horrocks’s direct command. Its total strength on paper was estimated at 470,000 men. To his south, Simpson’s army had been reinforced with additional units from Hodges’s U.S. 1st Army for a total troop strength of 378,000.

The low-lying regions in much of Holland and along the upper Rhine consisted of marshland drained by dikes. To slow the advance of the First Canadian Army, the Germans had flooded the marshlands north of the Reichswald, creating a shallow lake 10 miles wide and 40 miles long, making the area unsuitable to the Allies for anything other than amphibious operations. In the run up to Veritable, this meant that Horrocks’s XXX Corps, which would advance east along the Nijmegen-Kleve road and through the Reichswald, was sandwiched into an eight-mile front between the flooded Rhine and the Maas River, making it impossible for Horrocks to bring the full weight of his forces to bear in the initial attack. Because of the flooding, the division commanders would be able to commit just one or two of their brigades in the initial attack.

Despite being outnumbered in men and material, the Germans would enjoy distinct terrain advantages. The Reichswald was a managed state forest in which old and new stands of timber were mixed together throughout an area five miles wide by eight miles long. The timber had been planted in a geometric fashion, and sections were divided by open lanes, known as “rides,” to facilitate logging. The rides, which ran east to west through the forest, provided excellent fields of fire for German 88mm guns. The rides were largely unpaved, rendering them unsuitable for armored vehicles. On the western edge of the Reichswald lay the outer layers of the Siegfried Line, consisting of extensive minefields followed by a double line of trenches protected by an antitank ditch.

Three miles inside the forest lay the main Siegfried Line. Here the Germans had incorporated a wide array of defensive features designed to defeat a determined assault, including a second antitank ditch, concrete pillboxes and reinforced bunkers, barbed-wire entrapments, and hundreds of machine-gun, mortar, and gun emplacements. In addition, the Germans had fortified the towns of Kleve and Goch, located at the eastern end of the forest, with a ring of barriers and trenches to prevent their capture. Crerar was keenly aware of the nature and extent of the fortifications that lay in front of his forces, and he knew they were in for a costly battle similar to that encountered by U.S. forces in the Hürtgen Forest the previous fall.

Blaskowitz may have had overall command of the German forces opposing the First Canadian Army, but Schlemm directed the divisions at the front. A veteran of many bloody battles on the Eastern and Italian Fronts in which he showed a knack for the fighting withdrawal, Schlemm had seven divisions organized into three corps under his command. The commander of the First Parachute Army planned to employ his forces in such a fashion as to parry the Allied attacks and launch well-planned counterattacks when opportunities arose. He believed this approach was necessary to keep the Allies from gaining the west bank of the Rhine which, if they were to do so, would enable them to halt barge traffic that transported coal and steel vital to Germany’s war machine.

Schlemm placed his strongest units astride the road that ran from Nijmegen to Xanten, skirting the Reichswald to the north. The German right flank, well back from the main lines in the vicinity of Kalcar, was anchored by the XLVII Corps under the command of General Heinrich von Luttwitz, consisting of the 116th Panzer Division and 15th Panzergrenadier Division and augmented by the 6th Parachute Division from the Twenty-fifth Army stationed in Holland.

The center was occupied by General Eugene Meindl’s II Parachute Corps, comprising the 7th and 8th Parachute Divisions stationed east of the Reichswald, and the 10,000-strong 84th Infantry Division holding the western edge of the Reichswald. The left flank guarding the open terrain between the Reichswald and the Maas River was occupied by General Erich Straube’s LXXXVI Corps made up of the 180th and 190th Infantry Divisions. In addition to moving 2,000 experienced paratroopers into the Reichswald to stiffen the resolve of the questionable troops of the 84th Infantry, Schlemm also committed 36 self-propelled artillery vehicles and four battalions of heavy artillery to the defense of the forest. A number of 88s were incorporated in the main Siegfried Line, but Hitler would not allow Schlemm to move them from their static positions.

Crerar had developed a three-phase plan for Operation Veritable. The first phase called for the capture of Kleve, which Horrocks hoped to achieve within the first 24 hours, and also the clearing of the Reichswald. To achieve that ambitious timetable would require low temperatures that would keep the ground frozen and allow for the rapid advance of Allied armor, and also the assistance of the U.S. 9th Army to tie up German reserves and keep them from launching counterattacks against the First Canadian Army. The second phase involved establishing a north-south line that ran from Kalcar to Udem to Weeze and included the capture of Goch. The third and final phase consisted of securing a line from Xanten to Geldern and seizing high ground known as the Hochwald Layback. Although he hoped for a rapid breakthrough, Crerar realized the whole campaign might last three weeks.

Horrocks drew up the plans for the initial assault entrusted to four divisions backed by three armored brigades from the British Guards Armored Division. The 15th Scottish Division would push east toward Kleve from Nijmegen. The 51st Highland Division would assault the northern Reichswald, while the 53rd Welsh pressed its attack on the southern Reichswald. These three divisions would receive substantial armored support, even though the armor designated for the Reichswald was likely to get bogged down on the soft rides.

The 2nd Canadian Infantry Division would play a limited role on the first day assisting the 15th Scottish Division and then take on a much more prominent role in the second phase of the operation. To deal with scattered German strongpoints in the flooded area between the Nijmegen-Kleve road and the Rhine, the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division, which had extensive experience in waterborne operations in Normandy and Holland, would make an assault in amphibious vehicles. In the land-based assault into the Reichswald and along the Nijmegen-Kleve road, the attackers fielded 50,000 troops initially against 12,000 defenders, thus outnumbering them by more than four to one. For the overall operation, the First Canadian Army had at its disposal 500 tanks and 500 “funnies,” a term that referred to a host of specialized armored vehicles including mine clearers, flamethrowers, bridgelayers, and others.

The British Bomber Command sent 1,200 heavy and medium bombers into the night sky on February 7. The heavy bombers concentrated on reducing the towns of Kleve and Goch to rubble, while the medium bombers pummeled smaller towns such as Kalcar, Udem, and Weeze. After the bombers were on their way back to their bases at 5:30 am, Crerar’s First Canadian Army unleashed a devastating artillery barrage on the German positions. Taking his cue from Montgomery, who believed strongly in the use of artillery before and during a major operation, Crerar had assembled more than 1,000 guns from units at the corps and divisional levels. The barrage was intended to blast trenches and bunkers and also strike terror in the hearts of the defenders.

Fiebig, whose headquarters was located in Kleve, realized that a major assault from the direction of Nijmegen was imminent and issued orders for his forward units to abandon their positions and fall back to the main Siegfried Line. The majority of his units did not respond to the order because they were either destroyed or unable to pull back until the shelling let up. From his headquarters at Emmerich, Schlemm dispatched orders to the commanders of the 6th and 7th Parachute Divisions to prepare their troops for battle.

The infantry and armored attack began at 10:30 am on February 8. Horrocks employed a rolling artillery barrage in front of the attackers as a protective screen. Much to the disappointment of Crerar and his staff, a thaw had occurred several days before the start of the operation and the heavy rains that followed turned the ground to mud. The rain, which would continue for the next five days, raised the height of the floodwaters to the point that they covered sections of the Nijmegen-Kleve road, making it impassable to tracked and wheeled vehicles. Thick cloud cover prevented tactical aircraft from supporting the advance.

Major General Colin Barber, who commanded the 15th Scottish Division, was able to advance two of his three brigades along the corridor north of the Reichswald that led to Kleve. The 227th Brigade advanced along the Nijmegen-Kleve road toward Kranenburg, while the 46th Brigade drove for the village of Frasselt. The infantry began its assault in Kangaroo armored personnel carriers. Because the Scotsmen were advancing along the fastest route to the Rhine, they received substantial armored assets, including 170 Churchill tanks, two squadrons of Crocodile flame-throwing tanks, and two regiments of various other special vehicles.

The 2nd Canadian Infantry Division captured the village of Wyler just outside Nijmegen from the Germans in a pincer movement on the first day to allow the 15th Scottish Division to concentrate on bigger prizes. Horrocks’s plan was for the 15th Scottish to capture Kleve as quickly as possible, after which he planned to relieve the exhausted Scotsmen with the 43rd Wessex Division, which would wheel south toward Goch to carry out the second phase of the operation. The 227th initially found the going easy, but when the brigade crossed into Germany the Churchills and Kangaroos came under heavy fire from 88s. By virtue of larger numbers the Churchills prevailed, and the 227th closed on Kranenburg, the first of two significant towns west of Kleve.

At Kranenburg, the Scottish infantry came under a withering fire from German machine-gun nests sheltered in houses and buildings on the outskirts of the town and, as a result, began a mortar barrage that enabled the riflemen to clear out the defenders. By 5 pm, the 227th had captured the town. Immediately to the south, the 46th Brigade relied on its Crocodiles to torch the houses in Frasselt. The conflagration that tore through the village demoralized soldiers from Fiebig’s division, who were subsequently rounded up and sent off to the rear under guard. By 5 pm, Frasselt also was in Allied hands.

After its capture of Kranenburg, the 227th found that it could no longer proceed along the paved surface of the Nijmegen-Kleve road as it was covered by two feet of floodwater. The infantry dismounted from the Kangaroos and proceeded to assault Nutterden, which was situated in the strongest part of the Siegfried Line. Despite a lack of supporting armor, the Scotsmen managed to secure Nutterden the morning of February 9.

To keep up his division’s momentum, Barber committed the 44th Brigade, his reserve, to press the attack on the main defenses of the Siegfried Line. The capture of Frasselt gave the brigade unhindered access to the 15-foot antitank ditch a few hundred yards beyond the village. Before nightfall, engineers accompanying the 44th Brigade laid three bridges across the antitank ditch, and Kangaroos bearing infantry assaulted the far side while Churchills and Sherman Crab flail tanks provided cover against German fortified positions. Shocked by the speed of the assault, enemy troops from Fiebig’s division promptly surrendered.

Because of the narrow front, the two British divisions assaulting the Reichswald initially were able to attack with only one brigade each. Maj. Gen. R.K. Ross led the 53rd Welsh Division on the left, and Maj. Gen. Thomas Rennie commanded the 51st Highland Division on the right. The immediate task before Ross was to clear a series of hills, known as “features,” on which the Germans had gun emplacements that could shell the 15th Scottish Division as it drove for Kleve. Another objective was to cut the Kranenburg-Hekkens road to prevent the Germans from using it to funnel troops into the fight.

Like their fellow units in the British XXX Corps, the 71st Brigade of the 53rd Welsh Division found the inexperienced enemy soldiers of Fiebig’s 84th Division, which occupied the western fringe of the Reichswald, more than willing to surrender without a fight. It was not until the Welshmen reached the Brandenberg feature that they met enemy resistance. Atop the Brandenberg, the Welshmen came up against experienced paratroopers in fortified trenches protected by rows of barbed wire. Savage fighting raged throughout the first half of the afternoon, but by 3:30 the feature was firmly in the hands of the Welshmen. The paratroopers who survived the battle withdrew to the main Siegfried Line to continue the fight. At 11 pm, Ross relieved the 71st Brigade and sent the fresh 160th Brigade into the fight.

Some of the hardest fighting on the first day occurred in the southern Reichswald. It was there that the lead elements of the 51st Highland Division ran headlong into the majority of the 2,000 paratroopers that Schlemm had shifted into the forest before the battle began. The 154th Brigade advanced first, reinforced by elements of the 153rd Brigade. Before reaching the forest, the 154th had to clear the village of Breederweg, after which its Churchills came under fire from German antitank guns at the forest edge. The fighting was so fierce that the 154th did not reach the edge of the forest until nightfall, at which point Rennie sent the 152nd Brigade into action. By morning on February 9, Rennie had all three of his brigades in action and had sent part of the 153rd Brigade south to cut the Nijmegen-Gennep road, denying its use to German reinforcements that might join the battle.

The Canadian 3rd Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Dan Spry, launched its attack on the fortified villages in the flooded zone south of the Rhine at 6:30 pm. The water rats, as they were called, sailed across the lake in Buffaloes and other amphibious vehicles outfitted with machine guns and bazookas to provide covering fire. Hawker Typhoon aircraft had rocketed positions earlier in the day to soften them up, and the assaulting infantry made rapid progress floating easily over minefields and obstructions that would have slowed an attack over dry ground. During the night fighting, Spry’s water rats managed to clear the enemy from more than a dozen isolated villages and reduce the threat that enemy long-range artillery positioned in the villages posed to the 15th Scottish Division. The next day they pushed on to Millingen, which was situated on the Rhine, and prepared to advance south along the Spoy Canal toward Kleve.

On the morning of the second day, the First Canadian Army was poised to attack Kleve and to press its attack in the northern Reichswald against the main Siegfried Line. Despite the setback that the 51st Highland Division had experienced in the southern Reichswald against the paratroopers, Horrocks was more concerned with ensuring that his troops captured Kleve as quickly as possible to keep the attack on schedule. To ensure he had sufficient forces on hand, Horrocks sent a message to Maj. Gen. Ivor Thomas to prepare his 43rd Wessex to assist in the capture of Kleve.

On the German side, the first day’s battle had greatly reduced the strength of Fiebig’s 84th Infantry Division. Altogether, the division had experienced 3,000 casualties and had lost another 1,200 captured. Despite evidence that a major operation was under way, Blaskowitz clung to his belief that the Reichswald battle was a feint and that the main attack would come farther south. Therefore, he refused to allow Schlemm to commit his panzer reserves to the spreading battle. As a concession, Blaskowitz gave permission for Erdmann’s 7th Parachute Division to join the fight.

The heaviest fighting on the second day occurred at the Materborn feature overlooking the southern outskirts of Kleve as elements of the 7th Parachute Division rushed to occupy the crucial high ground. At the same time, the Scotsmen who had reached the western outskirts of Kleve were advancing on the Materborn. Heavy fighting occurred throughout the day as the two sides clashed on a spur of the Materborn known as the Bresserberg. Although the Scotsmen gained the upper hand and seized the crest of the spur, the paratroopers clung tenaciously to the eastern slope and fortified their positions on the second night of the battle using rubble from ruins on the southern edge of Kleve.

As the fighting raged at the Materborn, Horrocks fretted over the failure of his troops to take Kleve on the first day. Because of this, he ordered the 43rd Wessex Division into battle on the afternoon of February 9, hoping to capture Kleve on the second day of the operation. Unaware of the precise situation at the front, Horrocks later conceded that he acted prematurely given the road conditions. Since parts of the Nijmegen-Kleve road were closed to armored traffic on account of high water, the Wessex men were forced to use the same rides through the Reichswald that the 15th Scottish was using to bypass the flooded sections. The result was a traffic jam; and the 129th Brigade, which was the lead unit in the 43rd Wessex column, would not reach the front until the third day.

On February 9, a day before Operation Grenade was scheduled to begin, soldiers of the U.S. 1st Army finally captured the Schwammenauel Dam, the largest of the seven Roer dams. Although they captured the dam intact, they discovered the Germans had destroyed the discharge valves, resulting in a steady torrent of water that flooded the Roer valley and made it impractical for Simpson’s 9th Army to begin its attack on schedule. The stark implications were that Crerar’s First Canadian Army was on its own against the First German Parachute Army. To compensate Crerar for the delay, Montgomery arranged for two American divisions to take over positions on the front line held by the British Second Army’s 52nd Lowland and 11th Armored Divisions, which enabled those two units to reinforce the First Canadian Army.

The 15th Scottish Division reached the outskirts of Kleve on the third day of the operation. Ironically, it was not the Scotsmen who entered Kleve first, but the 129th Brigade of the 43rd Wessex Division, which, while trying to move into position to assist the attack from the south, accidentally took a wrong turn and wound up inside the town. A series of firefights broke out between the Wessex men and the town’s defenders, which included both Fiebig’s infantry and Erdmann’s paratroopers. The German defenders enjoyed superb defensive positions among the rubble and craters left behind from the aerial bombardment that preceded the operation. The fighting continued throughout the day, and gradually the Wessex men forced the defenders out of the southern section of the town. Meanwhile, the 15th Scottish Division brought up its heavy guns in preparation for a final assault the following day.

Realizing that the main Allied attack was indeed coming from the direction of Nijmegen and that the 84th Infantry Division was no longer an effective force, Blaskowitz gave Schlemm permission to feed more reinforcements into the battle on the third day of the offensive. As a result, the fighting grew in intensity south of the Materborn when General Hermann Plocher’s 6th Parachute Division arrived in the sector. Plocher’s crack paratroopers slowed the advance of the 43rd Wessex and the 53rd Welsh Divisions. Through a series of ferocious counterattacks, the paratroopers managed to hurl back the 53rd Welsh and keep it from crossing the Kleve-Hekkens road. Unknown to the advancing Allies, Schlemm had ordered the 116th Panzer and 15th Panzergrenadier Divisions to take up a position on the Kleve-Goch road from which they could not only check the Allied advance but also possibly attempt to retake Kleve should it fall.

On February 11, the 129th Brigade, 43rd Wessex Division broke off from the battle of Kleve to avoid friendly artillery fire from the guns of the 15th Scottish. Once that occurred, the 227th Brigade attacked Kleve, capturing the town by nightfall. It was assisted in its effort by units of the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division, which had advanced along the west bank of the Spoy Canal and linked up with the Scotsmen.

Thomas then replaced the battle-weary 129th Brigade with the fresh 214th Brigade, which he instructed to press its attack toward the Kleve-Goch road. House-to-house fighting occurred as the Wessex men steadily drove the Germans back. The Wessex men found well-camouflaged paratroopers darting from one fortified house to the next as they stubbornly fought to delay the Allied advance. Tanks were brought up to blast the paratroopers from their positions with high-explosive shells. To counter this, the defenders used Panzerfaust shoulder-fired antitank weapons to stop the armored vehicles. Despite tenacious fighting by the paratroopers, by day’s end the 214th had secured the town of Bedburg and the adjacent village of Hau in preparation for a shift southward toward Goch. Meanwhile, furious fighting in the Reichswald between the British 53rd Welsh and 51st Highland Divisions and the German 6th Parachute Division led to only limited gains.

Schlemm knew that it would be only a short time before the Allies had cleared the Reichswald of all its defenders. To buy the paratroopers time to fall back and form a new line, Schlemm ordered von Luttwitz on the morning of February 12 to launch a counterattack with his two panzer divisions toward Kleve.

Luttwitz’s 47th Corps was one of the best-led units in the German Army. What it lacked in resources, it made up for in the skill and cunning of its headquarters staff.

The 15th Panzergrenadier Division, led by General Wolfgang Mauke, took up a blocking position between the Reichswald and the forest of Kleve astride the Kleve-Goch road. Once this was accomplished, Mauke sent a battle group into the Reichswald with orders to strike north toward Kleve. Ross was pushing his division through the Reichswald two brigades abreast (the 160th on the left and the 158th on the right).

Mauke’s battle group ran headlong into the hard-fighting Welshmen a short distance from the Kleve-Goch road. The grenadiers tried to drive a wedge between the two supporting brigades, but the latter employed mortars and called in artillery to break up the German attack. The high-explosive artillery shells wreaked havoc on the grenadiers, blasting men and equipment alike. Meanwhile, the 116th Panzer Division under General Siegfried von Waldenburg circled around the forest of Kleve and struck the 214th Brigade of the Wessex Division, which was mopping up in Bedburg. The panzer division, which was tasked with blocking the road to the Rhine after the fall of Kleve, was only at half strength and could muster just 14 tanks, a mix of Panzer IVs, Panthers, and Tigers, for the counterattack. Like the Welsh brigade to its south, the 214th Brigade relied on its divisional artillery to blunt the counterattack and force the Germans to retire. By nightfall, the 53rd Welsh Division had gained the Kleve-Goch road, and Kleve remained firmly in Allied hands. Only the southeastern portion of the Reichswald remained in German control.

The heaviest fighting on February 13, the sixth day of the battle, took place east of the forest of Kleve as Thomas ordered two battalions, the 4th and 5th Wiltshires from the 129th Brigade, to try to flank the 15th Panzergrenadiers by pushing south on the Kleve-Udem road farther east rather than attempting to force their way through the grenadiers blocking the Kleve-Goch road. The Wiltshires pushed off in a driving rain, and the Sherman tanks supporting them quickly became mired in the mud. Fanatical fighting by paratroopers from the 6th Parachute, who were backed by armor from the 116th Panzer, made the advance difficult. The Wiltshires sought to clear German trenches and fortified farmhouses using little more than grenades and automatic weapons. That night, the Germans launched a ferocious counterattack with Panzer IVs and Tigers, overrunning a company of the 4th Wiltshire. The battalion managed to maintain the rest of its line despite the mayhem, and the Germans withdrew to their original positions.

On February 14, a week into the battle, Crerar divided his forces into two independent wings to carry out the second phase of Operation Veritable. After the capture of Kleve, the front had expanded from eight miles to 14 miles, allowing for additional Allied divisions to join the battle. On the left, General Guy Simonds, commanding the Canadian II Corps, would assume responsibility for capturing Kalcar. He would have command of the 15th Scottish Division for a few days before it was returned to XXX Corps.

On the right, Horrocks’s XXX Corps would drive south for Goch. One of the first orders that Simonds issued was for two brigades of the 15th Scottish Division to rest and refit before rejoining the XXX Corps in the attack on Goch. Not counting the 15th Scottish, Simonds had four divisions, two armored (11th British Armored and 4th Canadian Armored) and two infantry (2nd Canadian Infantry and 3rd Canadian Infantry), under this command. To assist the XXX Corps in its advance on Goch, the 52nd Lowland Division from the British Second Army would join the battle on the far right. Its job was to ensure that Staube’s LXXXVI Corps in Goch could not cut its way out to the south.

Allied morale received a substantial boost on February 14 when the skies cleared and friendly aircraft began flying sorties against German positions. On the right, Thomas would employ all three of his brigades, one after another, in the final advance on Goch. The 129th Brigade battled the 15th Panzergrenadiers east of the forest of Kleve on February 14. The following day, Thomas placed the 130th in the lead. Trying to stall the advance of the Wessex men, the Germans cobbled together a new battle group and launched several counterattacks against the Wessex men. When the 130th reached a state of exhaustion on the afternoon of February 16, Thomas ordered the 214th Brigade to pass through its fellow brigade and renew the push south.

Following the fall of Kleve, the Germans had rushed reinforcements to the area just east of Kleve in the hope of delaying as long as possible the First Canadian Army’s advance to the Rhine. The 15th Scottish had made little progress east on its own, and Simonds intended to introduce fresh troops on the left wing to break through German resistance and capture Kalcar. The German paratroopers, who had cleverly entrenched in the Moyland Wood on the south side of the Kleve-Kalcar road, were particularly tenacious in their resistance and managed to inflict serious casualties on the Allied units sent to pry them loose.

While he waited for the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division to arrive from its location west of Kleve, Simonds ordered the 46th Highland Brigade of the 15th Scottish Division and elements of the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division to continue attacking the paratroopers. On February 14, the fighting was particularly heavy when the 46th Highland attacked the village of Tillemanskath just east of the Moyland Wood in an effort to isolate the paratroopers. The Germans used machine guns, mortars, and self-propelled artillery to turn back the Highlanders. When some of the Highlanders attempted to skirt the village using a sunken road, they were counterattacked and driven off.

On the right wing, Thomas sensed the German paratroopers and panzer troops he was battling were becoming exhausted, and he introduced the 214th to the battle late on February 16. Without allowing the Germans a respite, two battalions of the 214th advanced under cover of a rolling barrage with substantial armored support. The tanks blasted every structure the Germans might possibly use for cover as the brigade drove south. The force of the drive broke the German lines almost immediately, and the 214th was able to advance two miles against light resistance.

When the 214th reached the village of Pfalzdorf, Thomas ordered a battalion of infantry to mount up in Kangaroos and sent the battalion east to cut the Goch-Kalcar road to prevent reinforcements from reaching Goch. That night he ordered another battalion to attack German outposts on the Goch escarpment in an effort to seize the high ground north of the town before the Germans could solidify their defenses. The night assault was a complete success, and by daylight the Wessex men were in firm control of their objective. Thomas’s unstoppable drive had carved a great swath in the enemy’s line, severed the connection between the Germans at Goch and Kalcar, and captured the high ground north of Goch. The success of the 43rd Wessex before Goch marked a turning point in the battle.

The Moyland Wood would occupy Simonds’s attention on the left wing for his first five days of command. Elements of the 6th Parachute Division occupying the woods put up tenacious resistance. From their concealed positions, the Germans occupying the wooded tract could fire on Allied troops advancing either north or south of their position. On February 15, a battalion of the 46th Highland Brigade attacked two knolls in the forest but was driven off by German mortars. After heavy fighting over a two-day period, elements of the 46th Brigade of the 15th Scottish Division and the 7th Brigade of the Canadian 3rd Division were able to capture the villages of Tillemanskath and Louisendorf, respectively, which further isolated the paratroopers in the Moyland Wood.

Fighting in the Moyland Wood continued on February 17 with the Allies managing to capture 150 paratroopers but failing to eradicate a group of defenders who clung to an area on the east end of the Moyland Wood no larger than 1,000 yards long and 500 yards wide. Daily reinforcements and long-range artillery fire from batteries on the other side of the Rhine River had sustained the German foothold.

Before the war, Goch had been a bustling commercial center with 10,000 residents. Bisected by the Niers River, it was a rail town with three major roads converging on it. Schlemm had not entrusted its defense to Straube, whose two infantry divisions occupied the town, but rather to Meindl, the shrewd commander of the II Parachute Corps. By the time the 43rd Wessex took possession of the Goch escarpment, the Germans had constructed two deep antitank ditches around the town to make it difficult for enemy armor to breach the defenses.

Horrocks mustered four Allied divisions for the final assault on Goch. On February 17, the 43rd Wessex consolidated its position on the left of the Goch escarpment while the 15th Scottish, having arrived from Bedburg, took up a position on the right of the escarpment. To the west, the 51st Highland, having cleared the last of the German resistance from the Reichswald, took up positions on the right of the 15th Scottish, and the 52nd Lowland moved to anchor the far right of the Allied line before Goch. Horrocks planned for the 43rd Wessex to make a diversionary attack on the left, while the 15th Scottish and 51st Highland launched the main attack on Goch from the west. Both attacking forces included a substantial mechanized element consisting of tanks, bridge carriers, and Kangaroos.

The 43rd Wessex began its diversionary attack on February 18 and successfully bridged both antitank ditches, which drew the bulk of the German forces to the north bank of the Niers River in an effort to halt the progress of the Wessex men. On the following day, the 15th Scottish began its advance but encountered heavy opposition from German infantry in pillboxes and fortified houses on the northern outskirts of town. The 51st Highland was more fortunate. The Highlanders swept into town on the south side of the Niers River against light opposition. Ferocious fighting engulfed Goch for the next 48 hours as the three divisions expanded their control of the town and worked to clear the Germans one street and one building at a time. Although the Allies could boast that they controlled Goch by February 20, it would take two more days for them to round up the last of the town’s defenders.

As Simonds continued in his attempts to dislodge the fanatical paratroopers from the eastern edge of the Moyland Wood, the Germans were marshalling additional panzer units for a major counterattack to stop the Allied advance on Kalcar. With instructions to use the unit only in an offensive capacity, the German high command issued orders for the Panzer Lehr Division to join Schlemm’s First Parachute Army. On February 17, the 1st Battalion of the Panzer Lehr arrived by rail from Wesel to Marienbaum. The battalion, which comprised two companies of Panther tanks and one company of Jagdpanther tank destroyers, joined up with two panzergrenadier battalions in preparation for its attack. The return of wet weather made it possible for the Panzer Lehr to make the 45-mile journey by rail undetected by enemy aircraft.

While the 7th Brigade of the Canadian 3rd Division continued to press its attack on the Moyland Wood, Simonds introduced the 4th Brigade of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division into the battle on February 19. General Fred Cabeldu sent his three regiments forward from Louisendorf with orders to seize and hold the Goch-Kalcar road. Two regiments, riding in Kangaroos and backed by tanks, advanced side by side toward the road, while a third regiment followed. On the left was the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (RHLI), and on the right the Essex Scottish.

The rainfall of the preceding days had turned the fields into a muddy quagmire, and the infantry had to dismount and proceed on foot. When Sherman tanks entered the action, they were quickly knocked out by 88s. By mid-afternoon, the RHLI had lost 11 tanks. The fighting grew in intensity as long-range artillery from across the Rhine sent high-explosive shells into the Canadian infantry in an attempt to break up the assault. German machine guns raked the Canadian infantry as it advanced. To drive off the enemy, the Canadians brought forward flamethrower sections that gave those who survived the flames no choice but to retire.

At 2 pm, the 116th Panzer attacked the Essex Scottish, managing to roll back its right flank, which had been left unprotected by the 43rd Wessex Division to its south. Nevertheless, by late afternoon both regiments had advanced 400 yards beyond the Goch-Kalcar road. At that point, Cabeldu sent orders to the Royal Regiment of Canada, which had been held in reserve, to prepare to join the fight the following day. When the sun went down, the Sherman tanks that participated in the daylong fight were sent to the rear to rearm and refuel. What seemed like a simple decision would prove to be a fatal mistake.

German artillery began shelling the Allied front line south of Kalcar that night in preparation for a major counterattack. The Panzer Lehr, which had arrived at the front, was reinforced the night of February 19 by an additional company of Panzer IV tanks. The Germans cobbled together the best men and weapons from the 47th Corps and the Panzer Lehr to serve in Battle Group Hauser, commanded by Colonel Paul Hauser, which would spearhead the counterattack. Battle Group Hauser was supported on the right by the 6th Parachute, and on the left by the 116th Panzer.

At midnight the ground shook and buildings shuddered as the tanks and tank hunters of Battle Group Hauser lurched forward toward enemy lines. In the first hours of the night assault, two Canadian battalions were overrun and the survivors scurried for shelter in slit trenches or cellars of ruined buildings in an effort to escape the onslaught. In one instance documented by the Essex Scottish regiment, an enemy tank stuck its gun through the front door of a building and blew it to pieces. Allied radios crackled with frantic voices from the front lines pleading for immediate artillery support. The 4th Brigade’s field artillery fired more than 5,400 rounds in the first 12 hours in support of the beleaguered infantry. By launching the counterattack, the Germans had bought themselves a respite of several days from the determined Allied advance.

At daylight on February 20, two Canadian tank regiments roared to life and entered the action. To stop the German tanks, the Canadians wheeled 17-pounder antitank guns into action, which temporarily checked the German advance. Matthews ordered the Royal Regiment of Canada to rescue the remnants of the Essex Scottish, which had become unraveled by the counterattack, and to stabilize the right side of his brigade’s line. As the Royal Regiment of Canada entered the fight, the Germans resorted to mortar fire in an effort to break up its advance.

At 7 pm, Battle Group Hauser launched a counterattack directly at the RHLI in an effort to overrun the regiment. While Panther and Mark IV tanks attacked head on, groups of German soldiers attempted to work their way around the regiment’s flanks in an effort to cut it off from supporting units. Once again, the intervention of Allied tanks and antitank guns stabilized the situation.

The attacks by Battle Group Hauser and its supporting units on the 4th Brigade continued for a full week. As the fighting dragged on, the officers and men of the First Canadian Army learned that the Americans had at last crossed the Roer on February 23 and begun a steady drive north in an effort to link up with the First Canadian Army. Meanwhile, the battle around Kalcar seesawed as Canadian infantry and German paratroopers fought for control of key terrain features, even down to the hedges that surrounded fields and buildings.

The Germans launched daily attacks in an effort to break through the 4th Brigade’s front line, but Allied armor and artillery turned them back each time. On February 26, the Germans made an orderly withdrawal, leaving possession of the scarred landscape in the hands of Cabeldu’s men. The fighting along the Goch-Kalcar road resulted in 400 casualties for the 4th Brigade. That same day, the U.S. XVI Corps under Maj. Gen. John Anderson crossed the Roer at Hilfarth and began driving north on a course that would link up with the elements of British XXX Corps outside Geldern on March 3.

After more than two weeks of fighting, the First Canadian Army had punched through the northern section of the West Wall and expanded its front to 20 miles between the Rhine and Maas Rivers. The First Canadian Army had suffered a total of 6,000 casualties in the fighting. Exact German casualties are not known but were likely considerably higher. The Germans had squandered a major portion of their panzer reserves in an effort to turn back the attackers. Still, they had kept their forces intact and would continue to fight hard for every inch of ground in the Rhineland.

The capture of the Hochwald Layback, which was supposed to be the third and final phase of Operation Veritable, became part of Operation Blockbuster, which was launched on February 26. In the subsequent operation, the Canadians bore the brunt of the fighting. In five days of continuous combat that was some of the bloodiest of the war, Simonds hammered German fortifications in the Hochwald Layback until his forces finally broke through to Xanten.

By March 2, the Hochwald Layback was firmly in the hands of the Canadians. At that point, it was only a matter of days before the Germans retreated across the Rhine. Exactly one month after Veritable began, Schlemm ordered his troops to cross the Rhine and enter Wesel. In accord with Hitler’s orders, the Germans blew up the two bridges over the Rhine at Wesel two days later, denying them to the enemy. The battle for the northern Rhineland was over.

William E. Welsh, of Vienna, Virginia, previously wrote for WWII History on the Ju-52 and the Marder.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments