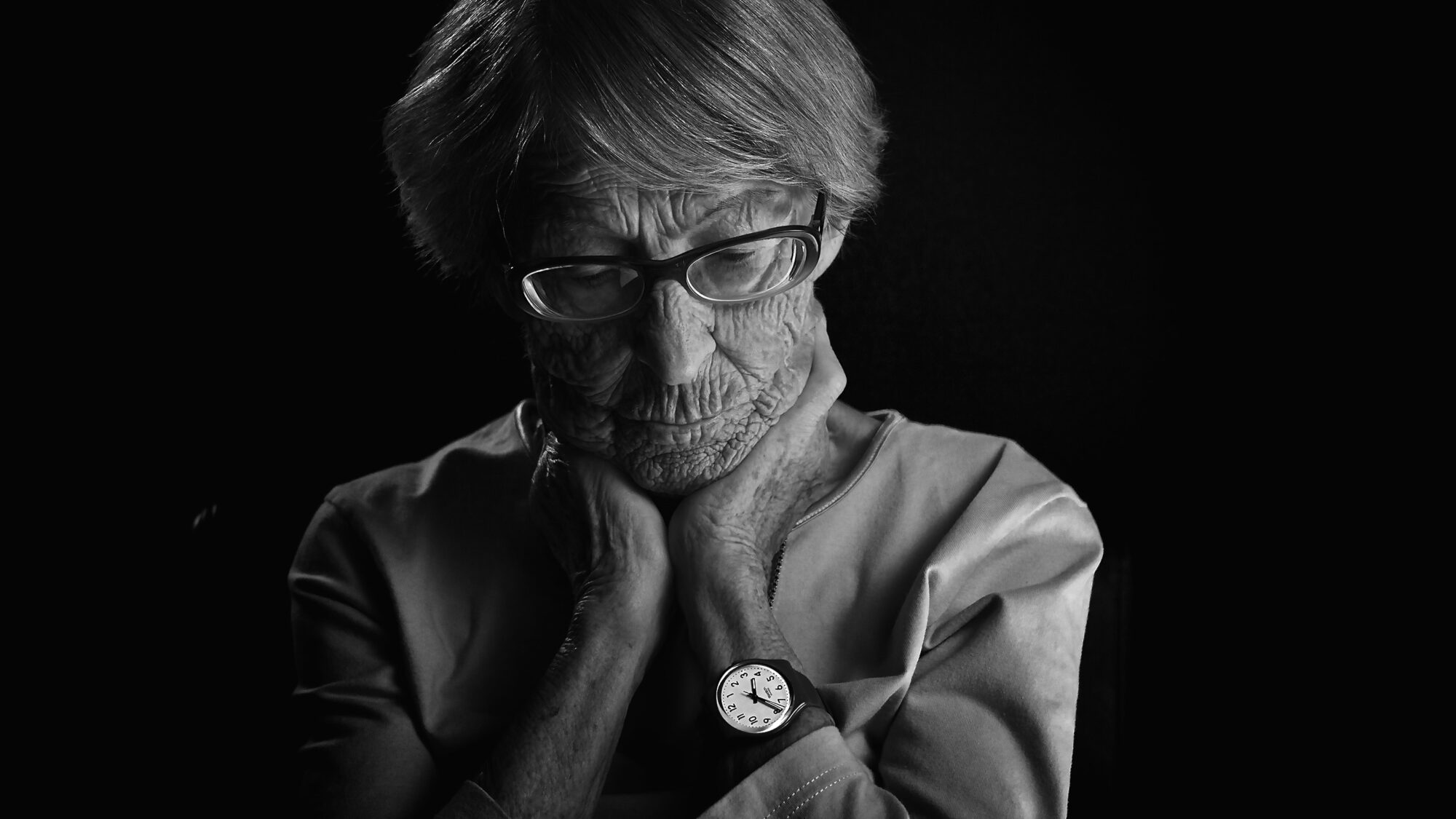

Over the past few months, several stories with a World War II connection have slipped into the news. One of the most compelling was about a German TV documentary called A German Life. The subject of the film is 105-year-old Brunhilde Pomsel, probably the last living person with a close, intimate connection to the Nazi center of power.

At the beginning of the film, she asks, “Is it bad, is it egoistical, when people who have been placed in certain positions try to do something that is beneficial for them, even when they know that by doing so they end up harming someone else?”

Frau Pomsel had been a personal secretary to Josef Goebbels, the Nazis’ propaganda minister, from 1942 until May 1, 1945—the day he killed his wife Magda and their six children before committing suicide at the besieged Berlin bunker.

Although she had been at the center of power for the Third Reich’s final three years, Pomsel called herself a “stupid and disinterested nobody from a simple background” and claimed that she “never knew about the Holocaust.” She described herself as “one of the cowards,” someone who was too “dumb” and “superficial” to grasp the larger picture.

In 1933, a friend in the Nazi Party got her a job in the news department of the Third Reich’s broadcasting station. She joined the Nazi Party in 1942 only to qualify for the prestigious, well-paid job at the Ministry of Propaganda, where she was one of four secretaries working under Goebbels and taking dictation until the end of the war.

“Why shouldn’t I?” she asked, with the same bland banality that so many other Germans from that era have exhibited when confronted by Nazi Germany’s horrific past. “Everyone was doing it.”

Pomsel remembers Goebbels, one of Hitler’s loyalists and the mastermind of the Third Reich’s viciously anti-Semitic propaganda machine, as being “an outstanding actor” who could go from being “a civilized, serious person into that ranting and raving hooligan.”

In 1943, just after Germany’s defeat at Stalingrad, Goebbels made what is called his “Total War” speech in which he called for “a war more total and radical than anything that we can even imagine today.” Pomsel said that she was there but “didn’t even realize what the speech was all about. I just didn’t listen,” she said in a recent interview, “because it didn’t interest me. That was a stupidity within me, I know this now.”

She said in the interview that she never had access to information about Nazi war crimes or mass killings, and that she learned of the Holocaust only after her release from a Soviet prison in 1950.

“We knew that Buchenwald existed,” she said, but believed it was a correctional facility. “We knew it as a camp. We knew Jews went there. I witnessed the deportation of Jews from Berlin.”

She dismisses those who would judge her: “The people who today say they would have done more for those poor, persecuted Jews—I really believe that they sincerely mean it. But they wouldn’t have done it, either. By then the whole country was under some kind of a dome. We ourselves were all inside a huge concentration camp.”

One of the film’s directors, Olaf Müller, warned, “The dangers are still alive. It could happen again.”

If you have a chance to see A German Life, take that opportunity.

Flint Whitlock, Editor

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments