By Blaine Taylor

The United States Naval Academy Museum at Annapolis, Maryland, is “an educational and inspirational resource for the Naval Academy Brigade of Midshipmen, other students of American naval history and thousands of visitors each year,” according to Shayne Sewell, assistant media relations director at the USNA Public Affairs Office.

First founded as the Naval School in 1845, the Naval Academy today is a four-year service academy that prepares midshipmen morally, mentally, and physically to be professional officers in the Navy. The Academy is located on 338 acres of land between the south bank of the Severn River and downtown Annapolis, 33 miles east of Washington, D.C., and 30 miles southeast of Baltimore.

The Yard, as the Academy campus is called, features tree-lined brick walks, French Renaissance and contemporary architecture, and scenic vistas of Chesapeake Bay. Bancroft Hall dormitory complex, the Cathedral of the Navy, and other 90-year-old buildings make the Academy a National Historic Site. Other facilities, such as the multi-purpose Alumni Hall, Nimitz Library, which contains more than half a million volumes, Rickover Hall engineering complex, and Hendrix Oceanography Laboratory, give the Academy state-of-the-art educational resources.

Bancroft Hall, named after former Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft, is home for the entire brigade of 4,000 midshipmen, and contains some 1,700 rooms, five miles of corridors, and 33 acres of floor space, making it one of the largest single domitories in the United States. All the basic facilities that midshipmen need for daily living are found in the hall.

Although the living areas of Bancroft Hall are off-limits to visitors, several other areas are open to the public. These include the vast Rotunda and Memorial Hall, dedicated to USNA alumni killed in action.

History is literally everywhere on the Naval Academy campus. Great moments and heroes in American naval and marine history are represented throughout the Yard in statues, paintings, ships, plaques, and buildings. The Marine Corps provides the honor guard for the superintendent’s home and also guards the Tomb of John Paul Jones, the venerable “Father of the Navy,” and all Academy gates. A statue of the Indian warrior Tecumseh is located in front of Bancroft Hall in T-Court. As designated “lord of football games,” Tecumseh is bedecked in full warpaint before all football games. For good luck, pennies and left-handed salutes are also thrown his way before exams.

The 600-member Naval Academy faculty is an integrated group of military and civilian instructors in approximately equal numbers. The student-faculty ratio is low, with most class sizes ranging from 10 to 22 students.

Midshipmen study such subjects as small arms, drill, seamanship and navigation, tactics, naval engineering, naval weapons, leadership, ethics, and military law during the four-year program. In addition, midshipmen train at naval bases and on ships in the fleet during part of each summer.

Upon graduation, midshipmen receive bachelor’s of science degrees in 18 major fields. They also receive commissions as ensigns in the United States Navy or second lieutenants in the Marine Corps, and must serve at least five years active duty as officers.

Initially, when Secretary Bancroft established the Naval School at then-Fort Severn in 1845, there were only 50 midshipmen enrolled at the school, taught by four officers and a trio of civilian professors. In 1850, the Naval School became the United States Naval Academy, the undergraduate college of the U.S. Navy. The current four-year curriculum was adopted that same year. During the American Civil War, the Academy moved to Newport, R.I., and after the Union victory of 1865 returned to Annapolis. The Academy museum is located in Preble Hall, and has a collection of more than 35,000 paintings, prints, and artifacts depicting naval history.

Using three-dimensional, graphical and audiovisual materials, the museum demonstrates the Navy’s role in defending and preserving the ideals of the United States.

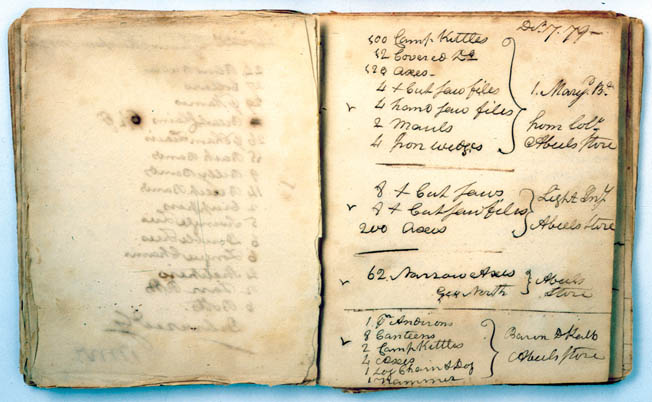

The museum began as the Naval School Lyceum in 1845, under the direction of the Academy’s first chaplain. The Lyceum was a collection of historic and natural objects, scientific models and apparati, and works of art brought together for study and discussion. In 1849, President James K. Polk directed that the Navy’s collection of historic flags be sent to the Naval School for care and display.

Other trophies of war, exploration and survey expedition artificacts, diplomatic mission mementoes, and works of art donated by naval officers, were forwarded by the Navy Department after the Civil War. The early collections of ordnance and ship models were used as teaching aids in the Academy’s Departments of Gunnery and Seamanship.

In 1888, the U.S. Naval Lyceum at the New York Navy Yard was disbanded and its large collection transferred to the Naval Academy. In 1921, the Academy also received the extensive collection of the Boston Naval Library.

The Naval Academy Lyceum of the 19th century was located in a room over the mess hall and later was moved to a former chapel. In 1910, exhibits were installed in Memorial Hall of Bancroft Hall. In 1920, then-Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Delano Roosevelt suggested that the collections be placed in a museum, and the ground floor of Maury Hall was made available for that purpose.

Through the generosity of the Naval Academy Athletic Association and the United States Naval Institute, the present museum building was constructed and opened in 1939. The Naval Institute funded an addition in 1962, and in 1970 the entire building was formally dedicated to the memory of Commodore Edward Preble (1761-1807), an officer of the quasi-war against France and the Barbary Pirate Wars. The museum’s holdings include ship models, paintings, prints, flags, uniforms, swords, firearms, medals, sculptures, manuscripts, rare books, photographs, ship instruments and gear, and a wide variety of personal memorabilia.

Within the Gallery of Ship Models are several noteworthy collections. Most of the vessels in the gallery are British, and are classified as “dockyard” models, indicating that they were built by official order of the Royal Navy’s ruling administrative council. Such vessels were constructed in England’s great dockyards, often under the direct supervision of the master shipwright. Some were built to demonstrate specific design features, such as a new system of steering or a change in the gunport configuration for certain classes of ships. All of the models in the museum were constructed with strict regard to scale: the most common ratio was one-quarter inch to the foot. The earliest models were built with an open-framed hull below the waterline.

Most of the models in the Class of 1951 Gallery were bequeathed to the Naval Academy in 1935 by Colonel Henry Huddleston Rogers, an American industrialist. Starting in 1917, Rogers acquired a collection of more than 100 ship models, some more than 250 years old. The collection was widely recognized during his lifetime as one of the world’s best in both quality and variety. In 1939, the Naval Academy Museum was opened specifically to display this collection, and the generosity of the Class of 1951 has permitted the Naval Academy to continue to honor Rogers’ wish to keep the collection intact.

It includes 108 ship and boat models of the sailing ship era dating from 1650 to 1850. Since 1993, the collection has been exhibited on the ground floor of Preble Hall. A video kiosk in the gallery provides in-depth information on both Rogers and the models in the collection.

The Robinson Collection represents the culmination of a lifetime of collecting by Beverley Randolph Robinson (1876-1951). Robinson scoured the galleries of the United States and western Europe in search of prints encapsulating the nature of naval warfare, principally in the age of fighting sail from the 1600s through the early 1800s. He purchased his first print while on vacation in London, and by 1933 his personal collection numbered nearly 200.

In 1933, Robinson offered to loan his collected works to the Naval Academy and indicated that he planned to bequeath them to the Academy’s Museum. He began sending prints in 1938 to coincide with the opening of Preble Hall.

From that time until his death in 1951, he continued to add historically important prints to the collection, which by then numbered more than 1,000 images. In accordance with Robinson’s will, a substantial trust fund was established to perpetuate the care, maintenance, and enlargement of the collection. In ensuing years, the collection has grown to more than 6,000 works of art.

Another valuable historical reference is the Malcolm Storer Naval Medals Collection, donated in 1936 and comprised of 1,210 commemorative coin medals dating back to 254 bc.

The United States Navy Trophy Flag Collection, begun by an Act of Congress in 1814 and given to the care of the Academy 35 years later, totals more than 600 historic American and captured enemy flags. Included are the famous “Don’t Give Up the Ship” battle flag flown at the Battle of Lake Erie, the first American ensign flown in Japan in 1853, and flags and banners that have been to the moon and back. Other significant holdings relate to John Paul Jones, Stephen Decatur, Oliver Hazard Perry, Matthew C. Perry, David G. Farragut, Chester W. Nimitz, William F. Halsey, and other prominent American naval heroes. A number of valuable naval documents acquired from the Rosenbach, Christian A. Zabriskie, and John L. Senior collections are available for research.

Within the large wrought-iron doors of Preble Hall and the entrance foyer paneled in pink travertine marble are four exhibition galleries totaling 12,000 square feet. The Main Gallery displays the history of the American Navy, from the Revolutionary War through Korea and Vietnam. It is arranged chronologically in a clockwise rotation beginning at the entrance to the Gallery.

The displays to the left of the doors deal with the Navy in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the engagements with the Barbary Pirates. Also displayed are mementoes of the Navy’s exploration of the Pacific and Arctic, of Matthew Calbraith Perry’s expedition to Japan in the 1850s, and exhibits from the Civil War, including some of the models of guns invented by John A. Dahlgren.

Moving to the right half of the gallery are exhibits on the Spanish-American War of 1898 and the wars of the 20th century, as well as data on the founding of the Naval Academy and its earliest years. In the back of the gallery is an exhibit funded entirely by Naval Academy alumni examining the role of the Navy, the Naval Academy, and its alumni in the 20th century, including the Cold War and America’s space program.

Within this gallery are two popular displays: the Naval Academy class rings and yearbook photographs of current Navy and Marine Corps leaders who have graduated from the Academy, including one President of the United States, Jimmy Carter, Class of 1947.

Highlighted in the museum are the table and green-and-gold tablecloth from the battleship USS Missouri and a deck chair from HMS Duke of York used in the ceremonies ending World War II in the Pacific, when the Japanese signed the Instrument of Surrender in Tokyo Bay. The uniform worn by Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz that day and a pen used in the surrender ceremony are also on display.

Admission to the museum is free, and it is handicapped accessible. The museum is closed on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day. Museum hours are Monday through Saturday, from 9am to 5 pm, and on Sunday from 11pm to 5m.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments