By Glenn Barnette and André Bernole

Early in 1944, German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the defeated hero of North Africa and now head of Army Group B in France, was tasked with strengthening the Atlantic Wall defenses against Allied invasion. This impossible task required fortification of 2,800 miles of coast—from the Arctic Circle in Norway to the French-Spanish border. Yet Rommel, despite his private misgivings that Germany was going to lose the war, went at it with his usual iron will.

In mid-May 1944, he was dispatched to the Mediterranean coast of France to inspect the preparations being made against possible invasion there. He was horrified to find that almost nothing had been done to discourage an Allied landing anywhere from Italy to Spain. He fumed at the commander of Army Group G, General Johannes Blaskowitz, in overall charge of southern France, and ordered him to get busy. Rommel then sped away to continue his work in the north.

Flush with humiliation, Blaskowitz immediately stepped up efforts to fortify the beaches and inland fields. Tens of thousands of mines were buried, and iron stakes were submerged just below the level of the tides, many with an artillery shell attached to rip open landing boats. More than 550 concrete casemates were constructed to house the guns that would defend the coast—whether the guns were available or not.

Farther inland, sharp stakes were planted in open fields to impale parachutists, and stout wooden poles were planted to rip open any gliders or planes attempting to land. These poles were about four inches in diameter and nearly 10 feet tall. They were crisscrossed with barbed wire, and many of the poles were rigged with Teller mines that would explode on impact.

On paper the German forces were formidable. Blaskowitz and General Friedrich Wiese, commander of the Nineteenth German Field Army, had 250,000 men available in 11 divisions to guard the 300-mile-long French Mediterranean coastline. But this strength was deceptive.

Three divisions had been detached in June to stem the Allied tide in Normandy, while other troops, trucks, tanks, and equipment had been requisitioned for the ever worsening Eastern Front. Two whole divisions were “static,” without transport of any kind, while a third division, the 157th, nominally in reserve, was completely occupied battling the French Resistance.

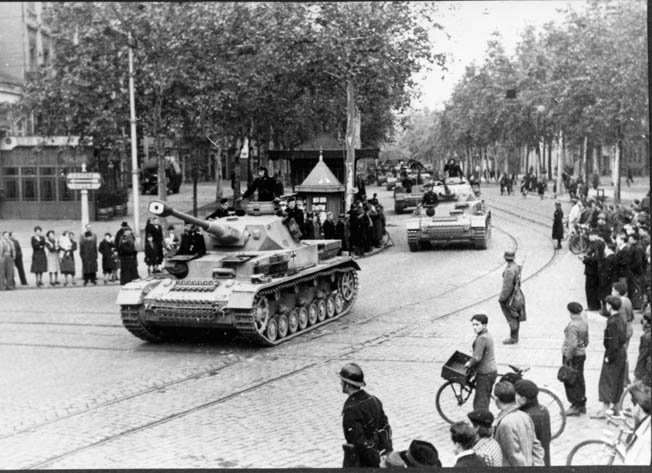

Only the 11th Panzer Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Wend von Wietersheim, had armored vehicles. Recently arrived from a mauling in Russia, it was only at half strength with a mere 75 tanks. Worse, it was stationed on the Atlantic coast at Bordeaux––some 300 miles away from where the landings would come.

To compensate for withdrawing the troops needed elsewhere, replacements—men who had been wounded in Russia—were forwarded to southern France. Yet these men were better than the conscripted or “volunteer” soldiers of Eastern European origin, most of whom were non-German speakers from Poland, Ukraine, Armenia, and elsewhere and were armed with a variety of obsolescent weapons gathered from all over Europe.

Although these replacements were commanded by German officers, they were considered unreliable—and would prove to be so. To make matters worse, Hitler had issued his usual order to fight to the last man. After the July 20 attempt on his life, confusion in the ranks reigned, distrust and suspicions blossomed, and decisions were crucially delayed.

While Blaskowitz frantically worked his men to exhaustion trying to fulfill Rommel’s orders, the Gestapo, Nazi Germany’s secret police, began rounding up leading figures in the French underground in a desperate attempt to break up the resistance movement collectively known as the Maquis. By this time the resistance was well established in southern France, but contrary to the situation reports received and distributed in London, they were not a unified force.

The Allies believed that 20,000 Frenchmen were armed and ready to fight. In reality, the French Resistance fighters were lightly armed and deeply divided. There were several different underground organizations that were mutually antagonistic. The Communists were the largest and best organized resistance fighters, but many others were loyal to Charles de Gaulle’s Free French movement. When possible, de Gaulle saw to it that his fighters got most of the Allied air drops of weapons and ammunition.

One such drop from a wing of 60 B-17s occurred two weeks before the start of Operation Dragoon. B-17 tail gunner Larry Stevens remembers, “We flew in formation at an altitude of 500 feet with our landing gear and flaps down to lower our air speed. We dropped 3,780 containers of who-knows-what to the Free French. I recall seeing multicolored chutes, and little people scrambling for packages.”

The pleasant German duty in the sunny backwater of the French Riviera came to an end on July 17, 1944, when American heavy bombers let go their loads on German facilities throughout the region in the opening round of Operation Dragoon. Guided by the French underground and Ultra intercepts of German communications, the Allies knew where nearly every German gun and strongpoint was located, and for a month they pounded the German positions.

Of course, the Allies had their own problems. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was adamantly opposed to a landing in southern France; he advocated landings in the Balkans that would sever Germany’s access to Romanian oil.

Churchill was planning ahead. An Anglo-American front in Eastern Europe would deny that area to the rapacious Soviets. As early as December 1941, Josef Stalin had laid out his postwar strategy to British Foreign Secretary Antony Eden. He told Eden that he planned to absorb much of Eastern Europe as a shield against Western Europe. Echoes of this strategy can be seen in Russia’s current relations with Ukraine.

Not surprisingly, Stalin endorsed the plan to invade southern France. Churchill was overruled by his allies, who wanted to focus on the war at hand, which meant the logistically easier invasion of Mediterranean France. As it was, the entire operation, then called Anvil, was put on hold after the near disastrous landing at Anzio in January 1944.

However, when Allied forces in Normandy became bogged down in tough fighting in the hedgerow country, plans were dusted off. The operation was renamed Dragoon and given the go-ahead on June 24. The name is said to have come from Churchill himself, who said that he was “dragooned” into the operation.

The Allies hastily prepared for their invasion to take the pressure off Normandy. The 3rd, 36th, and 45th Infantry Divisions of General Alexander Patch’s Seventh U.S. Army were pulled off the line in Italy and given a quick refresher course in amphibious landing. They were to be augmented by seven, mostly colonial, French divisions.

Meanwhile, a force of paratroopers and glider pilots also began training. In early July, Maj. Gen. Robert T. Fredrick was given command of all airborne troops for the invasion. He had five weeks to organize the First Airborne Task Force from scratch.

Crack teams of parachutists and commandos from 13 different units were pulled out of Italy and North Africa and hastily reorganized, trained, and briefed. One of these outfits was the antitank company of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which was an all-Japanese American unit.

Without knowing the reason, the Nisei gunners (like many other units) were hastily sent to Rome from their frontline positions in northern Italy. There they underwent three weeks of glider training with the Waco CG-4A glider, a flimsy craft made of metal tubing, canvas, and wood. The glider had no motor, no armor, and no guns. A Douglas C-47 could pull two gliders 350 feet behind it with 11/16-inch thick nylon ropes all the way to the drop site.

After only two glider practice flights, the gunners were deemed qualified for their mission. During this time it was discovered that their American-made 57mm guns would not fit into the gliders. Quick thinking resulted in the requisition of smaller British 57mm guns.

After that, Shiroku “Whitey” Yamamoto, a Hawaii-born jeep driver in the antitank company, explained, “We learned how to load a glider…. You can load your 57mm British antitank gun, or a trailer full of ammunition, or you can load up a jeep. So each glider carries only one wagon with ammunition, a jeep, or that British six-pounder.”

In all, Yamamoto’s company would employ 44 gliders. Two pilots from the First Airborne flew each glider, while three to six Nisei gunners from the antitank company rode inside. Their job would be to provide artillery support for the lightly armed independent 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment that would be making its first combat jump.

As thousands of men trained for the invasion, their mission became the most open military secret of the war. German POWs told their captors that the coming invasion of southern France was common knowledge, while Italian priests prayed openly for the success of the mission. It was a hard secret to keep.

There would be 300,000 men involved in Dragoon. As many as 2,000 planes and nearly 900 ships were assigned to the task along with 21,000 tanks, trucks, jeeps, and other vehicles that would be landed. The Germans could counter with fewer than 200 planes and no ship larger than a destroyer. The German Abwehr spy network was well aware of what was to come but could do little to prevent it.

There were constant American reconnaissance flights. The best plane available was the P-38 Lightning. With its heavy guns removed and a camera mounted, it could cruise at 30,000 feet, high above any German pursuit plane.

On the morning of July 31, at the Poretta airfield near Bastia in Corsica, a 44-year-old man climbed into his P-38 and strapped himself into the pilot seat. He wore the uniform of the Free French Armée de L’air. He had flown recon flights four years earlier in the Battle of France before escaping to North America. Now he was back in the war.

His name was Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, a famous French aviator who, in the 1930s, was one of the first to fly the mail from France to South America before embarking upon his career as an author. While cooling his heels in exile after the fall of France, Saint-Exupéry resumed his writing, producing his most famous work, Le Petit Prince, or The Little Prince. At his age he could have sat out the war, but he applied for a special exception that would allow him to keep flying––and it worked.

Now he was in Corsica, eager to do his bit, and had already flown eight missions. He took off at 8:25 in the morning for a long flight over southern France and the Rhône Valley. His mission was to take pictures of the Grenoble and Annecy region in the Alps. After his liftoff, he was never heard from again, and his fate remains a mystery.

On August 11, General Wiese learned that Allied troop convoys had shipped out from ports in North Africa. The Abwehr thought they were either headed for Genoa to get behind German defenders in Italy or to southern France; Wiese knew it would be France. General Blaskowitz, meanwhile, was desperately trying to move the 11th Panzer Division from Bordeaux into a defensive position along the Riviera to meet the possible invasion at the beaches. For that, however, he needed permission from Hitler, which would be late in coming.

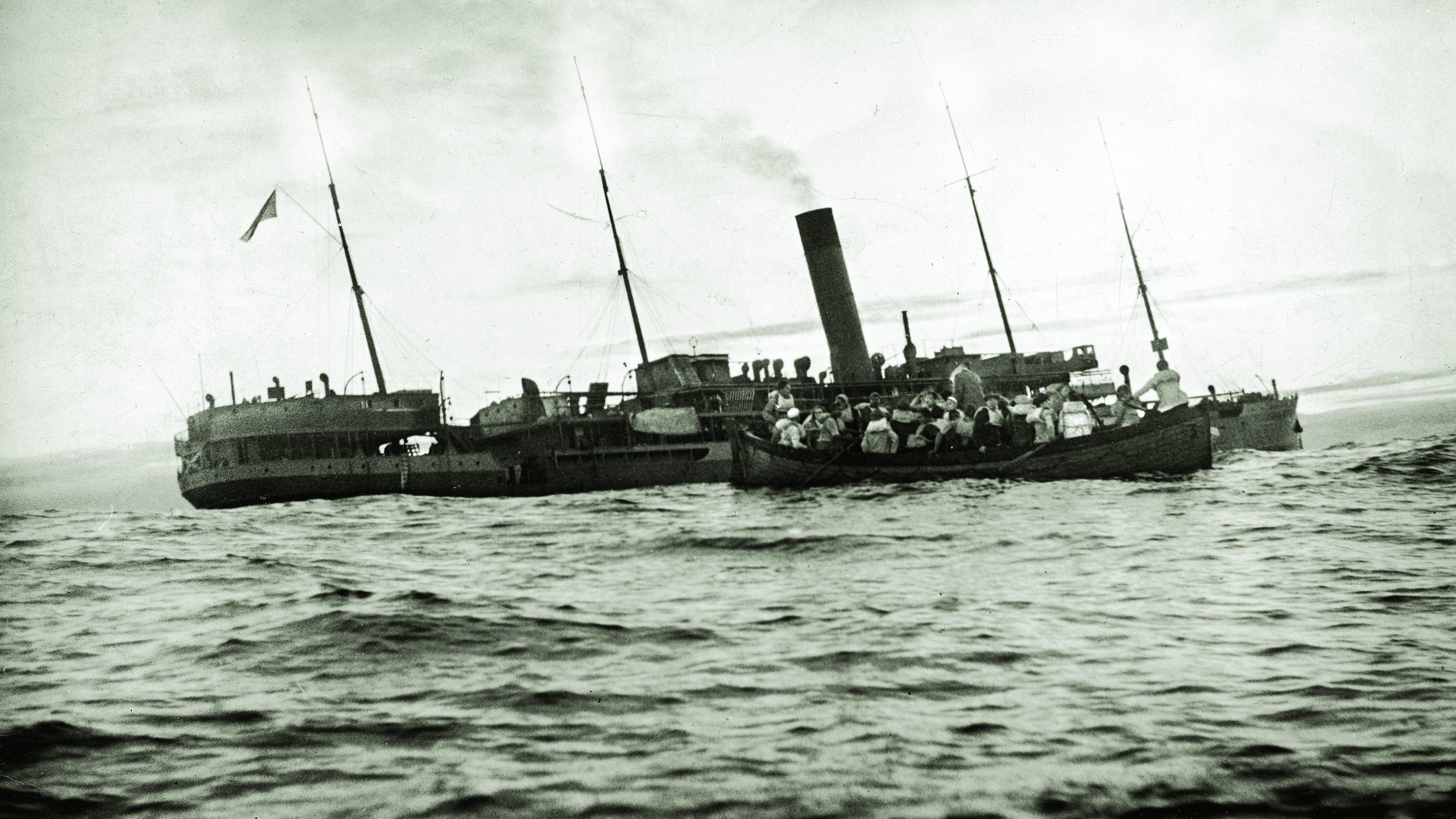

On August 12, Allied convoys departed their ports in Italy and headed northward to join up with the invasion force from North Africa. Altogether, Allied ships disgorged from 10 different ports in Italy, North Africa, and Corsica to create a mighty fleet.

To support the vulnerable troopships, 247 warships steamed as escort. They included five battleships, among them USS Nevada, which had survived the attack on Pearl Harbor (see WWII Quarterly, Winter 2015). There were also three heavy cruisers and nine escort carriers sailing in the Allied armada. Among the warships were vessels of the growing Free French Navy, Poland, and Greece. Many of the ships had come straight from Normandy, where they had bombarded the coast for that invasion two months before.

On that same day, several fighter squadrons—including the 332nd Fighter Group, the famed Tuskegee Airmen known as the Red Tails, flying from their base at Ramitelli, Italy—were dispatched to strafe German radar stations along the French Riviera. Their goal was to knock out the German radar prior to the landing.

Meanwhile, in Berlin the German high command, and Hitler in particular, had been convinced that an invasion along the Atlantic coast was coming. His information came from the same covert British agents of the XX Committee (the famed Double Cross) who had convinced him to keep an entire army in Calais to guard against an invasion there. As a result, Hitler would not release the 11th Panzer Division to the Mediterranean coast until August 14, the day before the invasion, when it would be too late.

As with Overlord, the Allies would employ several deceptions and diversions, known as Operation Span, to keep the Germans guessing and off balance. For this they even employed “star power.” Lt. Cmdr. Douglas Fairbanks Jr., the famous Hollywood actor, had joined the U.S. Navy at the beginning of the war and now commanded a small flotilla in an action called Operation Rosie. Fairbanks led 11 gunboats, PT boats, and motor launches whose job it was to land 67 French Navy commandos on the coast at Pointe de l’Esquillan, just west of Cannes.

The French disembarked at 1:25 am. They were to move inland and cause as much noise and destruction as they could to make the Germans think that this was the main invasion spot, but the landing was a disaster.

Reports from the resistance the day before stated that the landing beach was not mined, but after that report was received the Germans laid mines on the commandos’ landing beach. Exploding mines and the screaming of the wounded alerted the defenders, who rained machine-gun fire at the invaders and threw them back into the sea, where many more were killed or captured.

Saddened by the setback, Fairbanks would take heart when his ruse de guerre was reported by Radio Berlin to be a major Allied invasion that had been repulsed. The four small-caliber rounds fired by his gunboats were reported to be the salvos of several large battleships. Though most of the Frenchmen had given their lives, the gambit had worked.

Meanwhile, the American destroyer Endicott, under the command of Lt. Cmdr. John Bulkeley, was leading another deception. Earlier in the war, Bulkeley had been awarded the Medal of Honor when his PT boats rescued General Douglas MacArthur from Corregidor just before the Japanese overran the island in Manila Bay.

Bulkeley’s task was to lead a flotilla of PT boats and motor launches to the Baie de la Ciotat, a quiet bay between Marseille and Toulon. The boats were spread out over a 12-mile length and eight-mile width to simulate a major invasion fleet. In the dark, and with the help of radar-jamming strips of aluminum known as window or chaff, to confuse the local radar station (it had been purposely spared from Allied bombing), the tiny fleet was made to look like the real thing.

Bulkeley maneuvered his boats into the bay and began firing at the port facilities and German ships. The Germans responded with their shore defense guns but in the dark could see nothing. After making his pass, Bulkeley sailed back out to sea while the local garrison reported that they had repelled a major Allied landing attempt. On D+1, Bulkeley would repeat the ruse to keep the Germans guessing.

A third deception involved fake paratroopers. Three hundred dummies dressed in American uniforms were flown over Bulkeley’s fleet at Ciotat and dropped about 15 miles north of Toulon. They were rigged with firecrackers, which gave the impression of a firefight once they hit the landing zone. German troops were dispatched to the site only to find the dummies had been booby trapped; when a soldier tried to lift a dummy, an explosion went off and he was severely wounded.

Earlier that day the German 11th Panzer finally received permission to leave Bordeaux. It moved at dusk to avoid the Allied fighter bombers, but it had 300 miles to travel. At first it rumbled along on back roads but progress was slow. General Wietersheim ordered a move to the main road which, in the dark, would be reasonably safe.

On that same evening of August 14 at 7 pm, French Resistance leaders tuned to the French broadcast of the BBC as they had for months. Among a stream of seemingly meaningless phrases was the sentence, “Nancy a le torticolis,” or “Nancy has a stiff neck”—the coded signal that the invasion was imminent. After a few other innocent phrases came a second message: “Le chasseur est affamé,” or “The hunter is starving.” It was repeated. This phrase meant that the invasion would start early the next morning.

All along the Riviera, resistance groups swung into action. In St. Tropez, resistance leader René Girard heard the messages and gathered his section leaders to carry out their sabotage assignments. The men were cautiously optimistic, but they had been burned before. On June 5, the day before D-Day in Normandy, a similar BBC message urged a general uprising all over France. The Maquis in southern France rose up even though they were lightly armed and unsupported. The Allies finally called off the uprising on June 15. Unfortunately, by that time the Germans had already rounded up hundreds of men and women fighters. Torture, execution, or concentration camps were the fates of an unknown number of French patriots.

But on this night the resistance conducted several acts of sabotage that, by 10 pm, convinced General Wiese to order the entire Nineteenth Army on full alert. The resistance was active far beyond the Provence region and behind German lines. In Puligny-Montrachet, a village about 25 miles south of Dijon, a wine grower named Paul Cabanon had converted his rare, American-made Buick to run on wood-fired charcoal because there was no gasoline to be had. But the car always seemed to break down on a bridge that spanned a small brook.

Cabanon remembered that before the war a telephone cable had been laid down along the brook that was the main phone line between Paris and southern France. For weeks Cabanon swore and labored over his Buick on top of the bridge while a friend below dug away at the cement that encased the phone line.

When they heard on the BBC that the invasion would be the next morning, they sprang into action. While Cabanon’s wife sat in the car on the bridge as lookout, the two men poured 50 liters of sulfuric acid into a hole in the concrete and onto the cable. Then a small amount of plastic explosive with a delayed fuse was set.

When it exploded, the line was cut. Worse, 50 meters of cable were eaten away by the acid. It took two days to repair, which caused a blackout of German communications between Provence and Paris during the first two crucial days of battle. Cabanon escaped, but the Gestapo, looking for a Buick, arrested and tortured his wife before sending her to Ravensbrück, a Nazi concentration camp for women.

Back in Provence, the surviving German radar picked up the real Allied fleet making a change in course. Instead of sailing toward Genoa, it was now headed directly for the French Riviera.

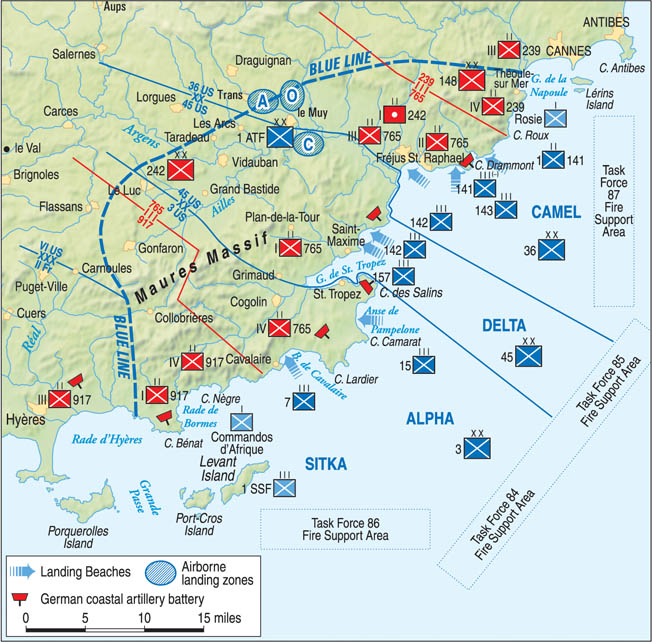

By 11 pm, the transports began arriving at their assigned positions some six to 10 miles off a 37-mile-long stretch of the French coast. At the western end of the line, transports carried the 2,000 American and Canadian commandos of Colonel Edwin Walker’s 1st Special Service Force—the famed Devil’s Brigade. Alongside them were 700 French commandos under the command of Lt. Col. Georges-Regis Bouvet.

The Americans were assigned to take two German-held islands some five miles off the coast of Toulon. One of these, the Île du Levant, was thought to house three 6.5-inch coastal defense guns, which could decimate the landing craft in the area. The other island, the Île du Port-Cros, also commanded the landing beaches. While the 1st Special Service Force hit these targets, the French commandos would simultaneously assault the mainland beach at Cap Nègre, east of Toulon.

Colonel Walker sent 1,300 men of the Devil’s Brigade, called the Black Devils by the Germans because they had painted their faces black during night raids at Anzio, against the seaward cliffs of Île du Levant. He reasoned that the cliffs would not be defended; he was right. The three guns that the Allies feared were there were nothing more than drain pipes convincingly camouflaged to look like guns from the air.

There was a garrison of Germans entrenched in an island cave that rained mortar shells down on the Americans when they came ashore. The British destroyer HMS Outlook provided fire support, but her shells could not reach the interior of the cave. For that, the attackers had to get close enough to fire bazooka rounds into it. At that point the Germans surrendered, and 240 prisoners were taken.

On Île du Port-Cros, meanwhile, the remaining Black Devils encountered some 58 Germans entrenched in a Napoleonic-era fortress called Fort L’Éminence with 12-foot-thick stone walls. The Germans pinned down the Americans, who were out in the open. When the cruiser USS Augusta was called in for fire support, her 8-inch shells bounced off the battlements. For two days the fort held out against periodic shelling and bombing. Finally, the World War I-era battleship HMS Ramilles was called in.

Though outdated, Ramilles, with her 15-inch guns, had been active throughout the war. Recently she had supported the landings at Normandy, knocking out shore batteries and breaking up enemy concentrations. Firing from six miles offshore, her third salvo found the fortress, and the defenders frantically waved white flags amid the smoke and surrendered.

On the mainland, the French commandos had their own problems. Two advance teams of nine men each were towed in rubber dinghies by PT boats to within 1,000 yards of shore. Their goal was the stretch of beach between Rayol and Cavalaire, from which they would signal with a green light to show the main body where to land.

Released from the towing boats, they silently paddled their rubber boats to the beach. Unfortunately, navigation errors put each group about a mile distant from its intended landing site. It cost valuable time to reach the intended beaches just east of Cap Nègre. This rocky outcropping was the site of three German costal defense guns. Groping in the dark, the first group at last found the right beach, but at the critical moment the batteries of their flashlights went dead and no signal could be sent.

The other group of nine landed at the base of Cap Nègre. The group leader, Master Sergeant Noel Texier, decided to change his mission. He would scale the heights with his eight men and capture the guns himself. But the Germans had been alerted, and a shower of hand grenades killed Texier and pinned down his men on the cliff.

At sea, the main body of commandos could not see any green lights to signal their landing sites. But the invasion could not wait. The next party, in two landing craft of 30 men each, was assigned to knock out the German guns on Cap Nègre. With no green lights from shore to guide them, they headed toward the wrong beach. The captain of the first boat saw in the darkness that they were not at a rocky shore and turned back out to sea.

The second boat, however, landed its men, who stormed the heights and knocked out the two guns they found (the reported third gun was not located). Despite the mishaps, the French now had a toehold on their beloved homeland.

While the diversionary raids were taking place and naval preparations were being made for a beach landing, the paratroopers of Frederick’s First Airborne Task Force boarded their C-47s at their bases in Italy, each man with a 70-pound pack of personal and company gear on his back, for an operation codenamed Rugby.

The British and American Pathfinders of the 509th, 551st Parachute Infantry, and the 550th Glider Infantry went first. These men were to prepare the landing sites for their units in designated locations around the town of Le Muy. Their job was to secure a perimeter and lay out landing lights. An hour later, 396 C-47 troop transports would follow.

Twelve miles inland, Le Muy was a strategically important town that commanded a narrow valley and one of the few roads that led inland. The Germans realized its importance and garrisoned it with two full regiments. It was a high-priority Allied target, and the paratroopers focused their drops around the town.

At 3 am on D-day, the Pathfinders approached the French coast only to find that it was covered in a thick blanket of fog. The men, under fire from German antiaircraft guns, had to jump blind. When they landed in darkness and fog, they had no idea where they were or where their mates were; some had landed up to 25 miles off target.

An hour and 15 minutes later, the main body of the 509th made its jump into the featureless fog below. In at least one case, an entire planeload of men dropped to their deaths into the unseen sea, carried to the bottom by their heavy packs. Many more were seriously injured upon landing. Like the Pathfinders, they had trouble finding their drop zone or their comrades in the dark and fog. Fifteen minutes later, 3,900 men of the 517th landed blind. Among those who were lost was General Bob Frederick, who was in overall command.

While there was much confusion among the Allied paratroopers, it caused even greater confusion among the enemy. As happened during the scattered Overlord drops, with Allied paratroopers landing far from their targets, they gave the impression of deliberate landings over a much larger area. For the defenders all was chaos.

Individually and in small groups, the paratroopers cut German communication lines, ambushed patrols, shot at vehicles, and took prisoners. There were firefights all over the Côte d’Azur. When reported back to German headquarters, the number of enemy combatants was always exaggerated, giving the impression that the Allied forces were numerically superior.

This was an accurate impression when the French Resistance was added in. These guerrilla bands attacked the occupiers wherever they could. In one incident, a company of 250 Germans had captured a patrol of Americans. No sooner had they done so than they were themselves surrounded by a greater number of angry Frenchmen.

The ranking German officer summoned one of his prisoners, a private, and surrendered his command to the Americans rather than trust to the tender mercies of the vengeful French. The private disarmed the entire company and turned them over to the French anyway. Yet, despite some small Allied victories, the Germans still held Le Muy.

Meanwhile, just before 6 am swarms of Allied bombers roared out of the south and dropped their bombs on the beaches while eager fighter pilots sought out a nonexistent Luftwaffe. Over 4,000 Allied sorties were made that day against no opposition. At 7:30, it was the turn of the naval guns to bombard the coast.

Just as the combined air and naval bombardment began, the troop transports, 10 to 12 miles from shore, began to lower their landing craft. By the time the troops reached the Rivera beaches at 8 am, it was hoped that all resistance would be subdued.

The main landings were accomplished by the VI Corps of the U.S. Seventh Army under the aggressive leadership of Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott. It would be bolstered by the French 1st Armored Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Jean de Lattre de Tassigny.

There were three landing beaches. From left to right they were Alpha, which was assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division; Delta, centered on the resort city of Saint-Tropez and assigned to the 45th Infantry Division; and Camel, assigned to the 36th Infantry Division.

Only at Camel Beach did German defenders put up serious resistance, but this was soon overcome.

Among the soldiers in the 3rd Infantry Division was the son of a sharecropper from Texas named Audie Murphy. He would soon be the most highly decorated American soldier of all time. His heroics in the south of France, where his best friend was killed, earned him the Distinguished Service Cross and were featured in his autobiography and in the 1955 movie To Hell and Back.

With much of their communications cut, the Germans could not offer a unified resistance, and it would be the next day before counterattacks could be launched.

All day Allied troops waded ashore, parachuted down, or landed in one of 400 gliders as the invaders consolidated their positions.

Shiroku Yamamoto recalled his entry into France on a glider: “As the men approached the green fields around Le Muy, they could see many colorful parachutes lying on the ground, like giant yellow, red, and blue morning glories. They also were greeted by bursts of antiaircraft flak. The tail of one glider was hit.”

There would be close to 300 casualties among the glider men alone. These were listed among the 1,000 casualties suffered by the First Airborne Task Force, one tenth of their strength. By the end of the battle, the count would be much higher.

There was only one bright spot for the Germans on D-day. A flight of Junkers Ju-88 and Dornier Do-217 bombers flew over the coast at St. Raphael around 9 pm after Allied fighters had retired. At least one of the bombers carried a Henschel He 293 antiship missile. Among the hundreds of ships at anchor below, the pilot selected the American LST-282, which was loaded with 1,000 men awaiting their turn to land. The pilot’s aim was true, and the LST sank in shallow water near shore, killing 40 and destroying the equipment aboard.

Tom Riordan, a mortarman in the 45th’s 157th Regiment, G Company, recalled, “On the morning of the 15th, we were aroused at two o’clock for breakfast. We ate quietly. ‘Hope this goes like the Anzio landing,’ an old timer said. ‘No Germans to meet us.’ Another replied, ‘Sure as hell not like Sicily. That was a real SNAFU.’

“Father Joe Barry, the 45th’s Catholic chaplain … reminded us there would be a Mass in the hold of the [LST] at 4 am. By 3:30 it was packed—GIs sitting on tanks, jeeps, trucks, boxes of ammunition, and rations.

“For Company G, the actual landing was a breeze. In our sector, heavy dawn bombardments by naval guns had silenced German pill boxes. Not a shot was fired by the Germans or us. Slogging through heavy sand, we saw French civilians watching at the edge of the beach. They were cheering. For me, there was one surprise. A plump, middle-aged French woman rushed towards us. Without warning, she planted a wet kiss on my cheek.”

By dawn the next day, the bulk of the Allied force was ashore, armed, and organized. The feeble German counterattacks did little good, but accidents did to some units what German defenders could not. On August 16, while the 157th Regiment of the 45th Division was off the shore of Saint-Tropez, a landing craft full of soldiers suspended from davits on a transport broke free and crashed onto another landing craft below it; 11 men were killed.

On the afternoon of D+1, the beaches were secure. By the 17th, it was clear that the Germans could no longer throw the enemy into the sea.

General Truscott, who had witnessed the disaster of troops digging in at Anzio, ordered immediate thrusts inland before the Germans could get organized. He got his way. The 3rd and 45th Divisions, spearheaded by the French 1st Armored Combat Command under General Aime Sudre, pushed westward north of Toulon and Marseille and on to the Rhône and Avignon.

The 36th Division, meanwhile, dug in on the eastern flank near Cannes to guard against potential German reinforcements from Italy.

Despite the cool morning fog, the subsequent days were hot and muggy. Everywhere in the battle men suffered from the heat and dust. But the scent of victory was in the air, and the Allied commanders were pushing their men forward to take advantage of the situation.

German positions were crumbling all over France. In the north, an entire army was trapped in the Falaise Pocket. French citizens rose up throughout the country to hinder the occupiers’ movement and communication.

When German troops invaded France in 1940, they had moved faster and with more violence than the French and British could prevent. Now the situation was reversed. On the 16th, Hitler had at last agreed to authorize a pullback. Blaskowitz (and Allied commanders through Ultra intercepts) received the order the next day.

Most German units in the south were ordered to withdraw to northern France to form a defensive line between Dijon and the Swiss border, while the two divisions east of the Allied beachhead were ordered to Italy to reinforce the garrison there. For the static units, however, retreat was not an option as they were ordered to defend the port facilities to the last man.

As rapidly as General de Lattre’s infantrymen could come ashore, they were pressed westward to liberate Toulon and Marseille. De Lattre decided to attack both cities at once. He had learned from his French sources that Toulon was garrisoned by some 18,000 Germans, while Marseille was defended by 13,000 more. He also knew that the Germans had not prepared defenses against a landward attack.

Attacking Toulon on August 20, de Lattre’s men took just six days to force a German cease-fire. One of the strongest German positions was a fort at Cap Brun. French engineers tapped into the German phone line to the fort. A Free French colonel, speaking perfect German and pretending to be the fort commander’s superior, told the commander that he had new orders from Hitler himself: the garrison was to shout “Heil Hitler” three times, destroy its guns, and surrender. To the amusement of the French outside, the Germans obeyed the orders.

Meanwhile, at Marseille an armada assembled offshore to bombard German strongpoints. The honor of firing the first salvo was given to the French battleship Lorraine. Inside the city, Maquis fighters rose up in support of the Free French soldiers battling their way into the city. In the hills outside the city, 6,000 fierce Moroccan Berbers, called Goumiers, along with their pack mules blocked routes of escape. Both cities officially surrendered on the 28th. The French suffered 4,500 casualties but took 28,000 prisoners.

While the French were clearing the ports, General Truscott sent a flying column under Brig. Gen. Frederick B. Butler 50 miles north to try to cut off a German retreat up the Rhône Valley. But, as more Allied troops pushed inland, logistics became an issue. There were not yet enough trucks ashore to resupply the growing and fast-moving armies, and this inhibited Butler’s mission. Without sufficient fuel, artillery, or ammunition, Butler could not get significant forces across the Rhône Valley road near Montélimar, a town world famous for its candy nougat, quickly enough to cut off the German retreat.

The recently arrived German 11th Panzer Division, with infantry support, counterattacked Butler’s position for a week, which allowed many German soldiers to escape. The fight to bottle up the Germans lasted until the 29th, when the exhausted panzer unit was at last ordered northward as the rear guard gave way. This allowed the Americans control of the highway. They captured more than 3,000 prisoners who had failed to run the gauntlet.

Truscott would not stop to rest. The 3rd Division (including Audie Murphy) struck northward from Montélimar toward Lyon (170 miles inland) with the 1st French Armored Division marching in tandem to the west of the river. In the east, the 36th and 45th Divisions moved northward along the Swiss border. Resistance in most places was minimal and easily overcome.

Mortarman Tom Riordan of the 45th recalled, “Our orders were to keep moving until we ran into resistance. We force-marched for two days, mainly through rain, until reaching a little town called Le Luc—my baptism under fire. It lasted about 20 minutes. We set up our mortars, but they weren’t needed. The Germans has quickly pulled back off.

“Our company commander was about to signal us to move out when four French civilians joined him. They wore armbands with the letters FFI. We were seeing our first Free French resistance fighters. ‘Anyone in the outfit speak French?’ the CO asked. George Courlas stepped forward. The Frenchmen excitedly began to chatter and wave their arms. George listened carefully. “They say there’s a German Mark IV tank hidden in the next village, sir. They want to knock it out.”

“Okay, tell them to go and do it,” the CO said. And they did.

By August 31, the Americans had reached the outskirts of Lyon, France’s second largest city. However, the 11th Panzer, the only intact German force, was again deployed as rear guard and the Americans feared the possibility of house-to-house fighting. Units were deployed to flank the Germans with little success. When two scouting troops succeeded in getting behind the Germans, the panzers turned and mauled them badly.

By the night of September 3, though, the German rear guard pulled out of its positions and followed the disintegrating army northeast toward the Alsace-Lorraine region; Truscott’s three divisions and the 1st French followed immediately. The Allies’ supply lines were thinning, however, and French peasants volunteered their aging vehicles to augment the meager deliveries from the coast. They also supplied the Allies, especially the Free French, from their own stocks of food and wine.

On that same day, Allied cargo ships began unloading at the port of Marseille, and by the 9th, the entire French Mediterranean coast was in Allied hands. The final goal of Operation Dragoon was realized on that day when a patrol of de Lattre’s French Corps, racing north along the Rhône, met up with a patrol of Maj. Gen. Jacques Leclerc’s 2nd Free French Armored Division, which had landed at Normandy and recently liberated Paris.

Soon, all Allied troops in France would come under General Dwight Eisenhower’s overall command while the Maquis was disbanded by de Gaulle and its fighters absorbed into the French Army.

Despite a chaotic start, Dragoon had achieved all its objectives. The war would move into Germany, and the people of France could breathe free.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments