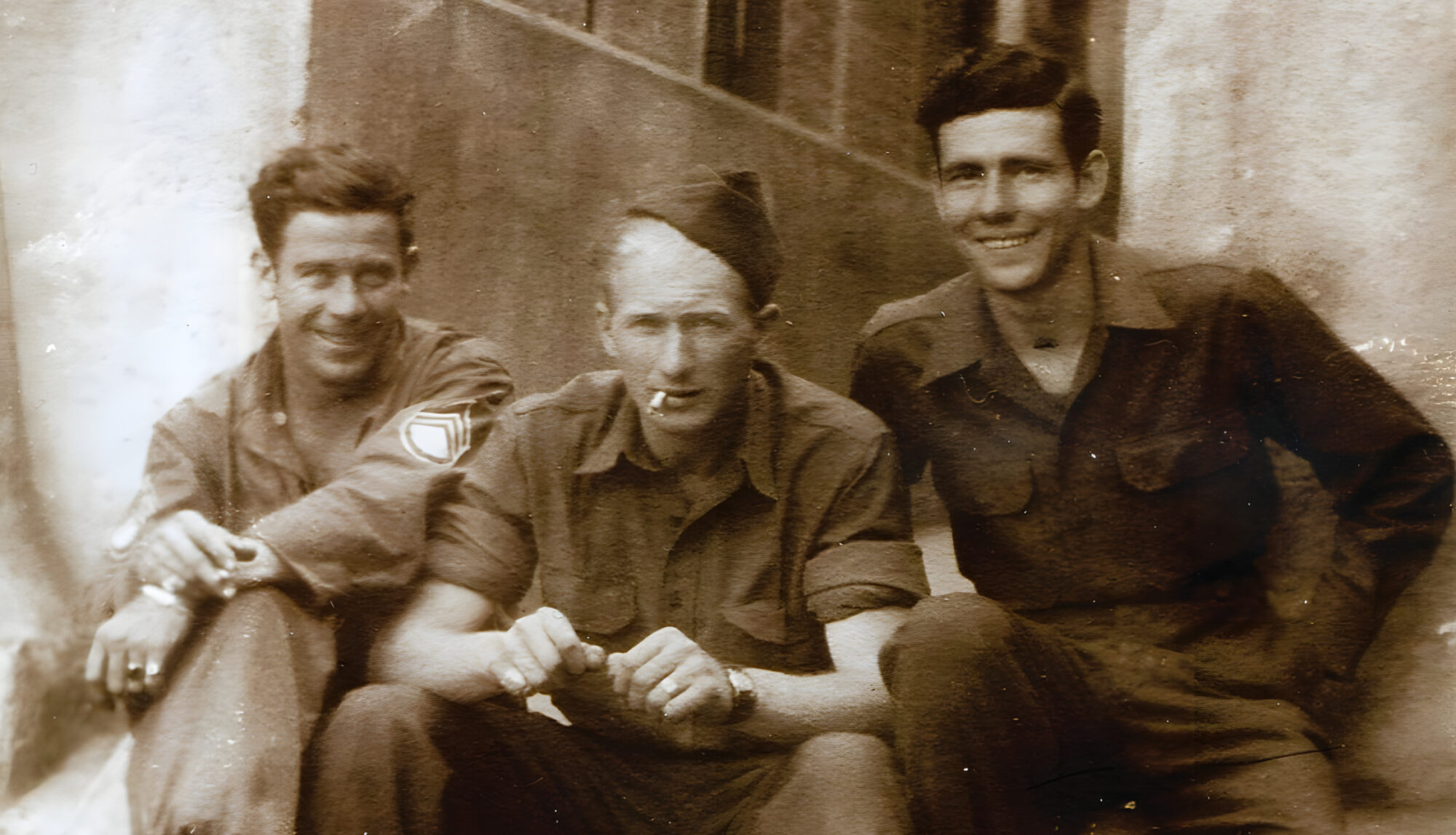

Like many true combat veterans, my father didn’t talk much about the war—in his case, World War II. We knew that he had served in France and Germany with the 79th Division, the famous “Cross of Lorraine” division. He carried his blue-and-white shoulder patch in his billfold, where he could see it every time he opened it. But he didn’t show it around, and the only time we ever saw the patch was when we asked Dad specifically to show it to us.

Because he was so reticent with details about the war, we treasured the few times Dad opened up a little about his experiences. He told us once about being drafted and sent to Fort Hood, Texas, for basic training. There was a military stockade on the base where prisoners from Rommel’s vaunted Afrika Korps were confined behind a barbed-wire fence. Dad said the sun-bronzed German POWs exercised in unison every morning, and he remembered wondering how he and his comparatively rag-tag buddies were ever going to defeat such tough, disciplined soldiers. Somehow they found a way.

Dad considered himself lucky to survive the war when so many of his buddies didn’t. He showed us the scar on his index finger where a piece of German shrapnel had struck him as he was leaping into a foxhole. A foot or so to the left, he said, and he would have been killed. And he told us about being sent to the rear with frozen feet a few days before the Battle of the Bulge. It seemed almost comical to us—not a real wound—but Dad said it had literally saved his life. When the Germans hit their lines, they killed several men in Dad’s platoon, including his sergeant, a man he knew only as Red. The sergeant had died before sending in his last roster report, and in all the confusion no one knew where Dad was. My mother, waiting back home in Nashville, received the dreaded telegram: “Missing in Action,” which people at the time understood to be a precursor to even worse news: “Killed in Action.” It was several days before Dad managed to get word to Mother that he was safe, if not entirely sound, in a military hospital behind the lines.

I asked my father once if he had ever been in any big battles. I’ve never forgotten his reply. “Son,” he said, “whenever some German-speaking SOB is standing behind a tree shooting at you, it’s a big battle.” All these years later, it still strikes me as one of the truest comments I have ever heard about ground-level combat.

I hadn’t realized when I began editing Arnold Blumberg’s article on the capture of Cherbourg that Dad’s division had been in the thick of the fighting there. In fact, the 79th was the first American unit to enter the city. Reference to the hedgerows on the Cotentin Peninsula recalled another of Dad’s sparing comments about the war. “Those damned hedgerows,” he would say, shaking his head. His expression said it all.

At Dad’s funeral in January 2006 at National Cemetery in Chattanooga, a squad of soldiers fired the traditional salute for a fallen comrade. I remember thinking then how loud the shots sounded in the clear, brisk air. It was a sound my father, a combat rifleman, must have heard many times during World War II, but like other members of the Greatest Generation, he modestly chose to keep the echoes to himself.

Roy Morris Jr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments