By Michael D. Hull

Fearless, demanding, and inspirational, General George Smith Patton, JR., was generally recognized as the U.S. Army’s outstanding field commander by the end of World War II. After only 13 months of combat command—less than a week in Casablanca, a month in Tunisia, 38 days in Sicily, and 318 days in Northwest Europe—Patton achieved fame and respect unparalleled in American military history.

Patton revitalized the under-performing U.S. II Corps after its rout at Kasserine Pass, boldly led the Seventh Army across Sicily—where the Americans came of age as a fighting force—launched his legendary Third Army on a series of spectacular armored thrusts to the German border, and, in one of the most remarkable movements in military history, turned his army northward to hit the southern edge of the enemy counteroffensive in the Ardennes in December 1944. He relieved besieged Bastogne and, with British help, disrupted the German advance toward strategic Antwerp. His recipe for victory was, “Hold them by the nose and kick them in the rear.”

After crossing the Rhine at Mainz in March 1945, during which Patton paused to ceremoniously urinate in the river, the Third Army drove into the heart of Germany and ended the war in Czechoslovakia and Austria. Patton ended the war with the respect of allies and foes alike, as well as a fourth star, elevating him to the rank of full general in April 1945. His last post was as military governor of Bavaria.

His image had become widely known. Nicknamed “Old Blood and Guts,” Patton wore highly polished boots, ivory-handled revolvers, and a stern expression as he strove flamboyantly to project the qualities of what he perceived as a successful general. The California-bred scion was a complex figure: profane, volatile, vain, and sometimes childish, yet also kindhearted, religious, and cultured. He was an incurable romantic, had wide-ranging interests, and wrote poetry.

Though a posturing fire-eater on the battlefield, he was also a meticulous planner. After taking part in General John J. Pershing’s ill-fated punitive expedition into Mexico against Pancho Villa in 1916 and leading a tank brigade in the St.-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne campaigns in September 1918, he spent the interwar years helping to create an effective American armored force.

Despite his feats and well-deserved renown, though, “Georgie” Patton became a lonely and frustrated man after the end of the European war. The death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt had distressed him deeply, and peacetime uncertainty, with the spread of communism threatening Europe, made him uneasy. Patton did not relish the daily routine of military occupation. As Colonel George Fisher, the Third Army chemical officer, observed, “Instead of killing Germans, what he knew best, Patton is asked to govern them, what he knows least. It won’t work.”

Furthermore, because of his well-publicized candor, which periodically raised official hackles, Patton ended up repeatedly in the doghouse. His career almost ended in the summer of 1943, when he verbally abused and slapped two shell-shocked soldiers at field hospitals in Sicily, after which he tried tearfully to apologize to thousands of assembled troops. He again made headlines in April 1944 when he addressed a British-run service club for GIs in Knutsford, Cheshire, and said, “It is the evident destiny of the British and the Americans, and of course, the Russians, to rule the world.” He spoke off the record, unaware that a reporter was present.

He was severely rebuked by his boss, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, for his failure “to control your tongue.” If it happened again, Ike warned him, “I will relieve you instantly from command.”

Now, in the summer of 1945, as close associates abandoned him, the outspoken warrior was bringing more troubles upon himself. He accused Jews of influencing everything, from the shape of the postwar peace to his problems as military governor of Bavaria, and ranted at the Russians. “Hell, we are going to have to fight them sooner or later,“ he told Eisenhower’s deputy, General Joseph T. McNarney. “Why not do it now while our army is intact and we can have their hind end kicked back into Russia in three months?” The genial but long-suffering supreme commander, meanwhile, had run out of patience with his maverick friend and protégé.

The final straw for Ike came when Patton held a routine 15-minute press conference in the scenic spa town of Bad Tolz, south of Munich, on the morning of September 22, 1945, to defend his use of Nazi Party members in administrative jobs. “In supervising the functioning of the Bavarian government, which is my mission, the first thing that happened was that the outs accused the ins of being Nazis,” he declared. “Now, more than half the German people were Nazis, and we would be in a hell of a fix if we removed all Nazi party members from office.” He added, “The way I see it, this Nazi question is very much like a Democratic and Republican election fight. To get things done in Bavaria, after the complete disorganization and disruption of four years of war, we had to compromise with the Devil a little.”

This time, Patton had sealed his fate. When he learned of the comments, Ike, who had recently warned him to “stop mollycoddling the goddamn Nazis,” was furious. A number of stateside newspapers, which Patton had denounced as “semitic,” seized on the story. Some editorialized that Patton was unfit for occupation command and would have to go, while others demanded his immediate relief.

Eisenhower’s chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, telephoned Patton and suggested that he call another press conference to “set the record straight.” Patton complied, but he was less than contrite, and another tempest blew up in the newspapers. Ike fumed again, but after his legendary temper had cooled, he cabled Patton that he must have been incorrectly quoted, and invited him to “see me for an hour.”

Tired, grim, and uncharacteristically subdued, the outspoken general reported to Eisenhower’s spacious office at the I.G. Farben Building in Frankfurt on the afternoon of September 28. Patton knew that he was in for another tongue-lashing, but he believed that he could charm his boss and smooth things over. Ike wore his famous grin, but it was evident to Patton that his summons was deadly serious. He was told that his comments had embarrassed himself, Ike, and the Army.

Eisenhower told him, “The war’s over and I don’t want to hurt you, but I can’t let you be making such ridiculous statements. I’m going to give you a new job.” After Patton insisted that his remarks had been deliberately distorted in the press, Eisenhower delicately broached the main reason for the meeting: Patton was about to be relieved. Ike suggested that Patton take charge of the Fifteenth Army, a small headquarters organization set up to prepare a history of the European war. Shattered at being relieved from his beloved Third Army, Patton predictably recoiled at the idea of being “kicked upstairs” and given a “paper command,” but he reluctantly accepted.

After the meeting, there was no customary dinner and camaraderie, and Patton rode Ike’s train back to Bad Tolz. He was “very calm and very humble,” said his aide, Major Van S. Merle-Smith. Shortly after the fateful meeting, Ike and Patton attended a football game in Frankfurt, during which the latter cloaked his bitterness. At dinner later, Patton told his aide, “I’ve obeyed orders and done my best, and now there’s nothing left. I think that I’d like to resign from the Army so that I could go home and say what I have to say.” But Merle-Smith talked him out of it.

Bedell Smith informed Patton on September 30 that he was being replaced as Third Army commander by Lt. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., who had organized the first U.S. Ranger battalions in 1942 and distinguished himself in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and Southern France. The two spit-and-polish cavalrymen spent two days together before the change of command. One of Patton’s last official acts with the Third Army was to pin the Silver Star on Master Sergeant John L. Mims, his faithful Black driver since September 1940.

Patton was “terribly hurt for a few days” at losing the Third Army. In an October 5 letter to his devoted wife of 35 years, Beatrice, he wrote, “Like William Jennings Bryan, ‘my head is bloody but unbowed.’ All I regret is that I have again worried you.”

The handover of the Third Army reins was conducted late on the dismal, rainy morning of October 7 in the spacious Bad Tolz gymnasium. It was an impressive, formal ceremony, with massed army and national flags, ruffles and flourishes, and four corps commanders present because Patton did not want “Ike or anyone else to get the idea that I am leaving here with my tail between my legs.”

In a brief speech, he declared, “All good things must come to an end. The best thing that has ever happened to me thus far is the honor and privilege of having commanded the Third Army … Please accept my heartfelt congratulations on your valor and devotion to duty, and my fervent gratitude for your unwavering loyalty … Goodbye and God bless you.”

The army band struck up “Auld Lang Syne,” and Patton handed the Third Army colors to Truscott, who gave a brief and emotional speech. The two generals then left to the strains of the “Third Army March” and “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow,” after which a lunch was served in Patton’s honor. After listening to many tributes from corps and division commanders, he decided that he had had enough. He arose, squared his shoulders, and walked resolutely to his staff car. The Third Army train was waiting to take him to his new Fifteenth Army command in Bad Nauheim, 24 miles north of Frankfurt.

It was a heartbreaking day for Patton, but he was dignified and hid his inward fury. “Nothing in his dress or bearing reflected the torture of his soul,” reported Colonel Fisher. Beatrice Patton would never get over what she considered the Army’s betrayal of her husband. “He was crucified and thrown to the wolves,” she said. “Not one voice was raised in his defense.” She accused General Eisenhower of “cowardice toward the press.”

With his affectionate bull terrier, Willie, at his heels, Patton made himself known to the staff at his new Fifteenth Army headquarters. The 100 apprehensive officers jumped to attention when the grim-faced warrior strode into the mess. One of the officers was young Lieutenant John S.D. Eisenhower, who later became a distinguished military historian. “There are occasions when I can truthfully say that I am not as much of a son of a bitch as I may think I am,” said Patton. “This is one of them.” The relieved staff roared with delight.

Patton’s generous nature shone through that evening when he told the staff, “I have been here and have studied your work today. I have been shocked by the excellence of your work.” The officers were won over and devoted themselves to him as staunchly as had the Third Army staff. They worked hard.

While chafing in his new assignment and grumbling in his diary and his letters to Beatrice, Patton set out to enjoy himself. He smoked cigars, took long drives by himself, wrote a series of articles on leadership and tactics, and started work on his memoir, War As I Knew It. He was delighted when friends feted him at a lavish party in the Bad Nauheim hotel ballroom on November 11, his 60th birthday. He was back in the limelight, briefly.

Back in his office, Patton became increasingly tense and restless, pacing back and forth. He still seethed about his betrayal by Ike and the Army, thought long and hard about resigning, and fretted about the uncertain political climate in postwar Europe. “The whole damned world is going communist,” he complained to Beatrice. “The last U.S. troops to leave Europe will be fighting a rearguard action … I really shudder for the future of our country.”

Patton’s low spirits were relieved when he was greeted by cheering crowds, decorations, banquets, and champagne in a number of cities. His stops included Rennes, Chartres, and Paris, where he lunched with General Charles de Gaulle and visited Notre Dame Cathedral, the tomb of his hero, Napoleon, and the Folies Bergère. He garnered 10 citizen-of-honor citations, plaques, and “a tremendous case of indigestion” during the tour. More honors were heaped upon him in Rheims, Metz, Verdun, Luxembourg, and Brussels, where he was awarded the Croix de Guerre and a named a Grand Officer of the Order of Leopold. He also caught a bad cold in the Belgian capital.

Patton’s persistent melancholy abated a few days later in late November, when he journeyed to Scandinavia. Riding in a special train that had once been used by Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, he attended a cocktail party at the American embassy in Copenhagen and then continued to Stockholm, where he breakfasted with Count Folke Bernadotte, a prominent diplomat who had negotiated with the Nazis on behalf of the Allies, called on King Gustavus Adolphus V, and was warmly reunited with eight members of the Swedish modern pentathlon team, against which he had competed in pistol competitions at the 1912 Olympic Games.

In a letter to Beatrice on December 5, Patton announced that he would be home for a month’s leave at Christmas. He told her that he would fly to England and depart from Southampton aboard the 45,000-ton battleship USS New York on December 14. It was the general’s last letter to his wife.

Eisenhower had left Europe on November 11 to take over as Army chief of staff, and his successor was the dour, ruthless General McNarney, a skilled administrator and graduate of the famous West Point class of 1915. Patton had told Ike earlier that he did not care to serve under McNarney, “not because I had anything personal against him, but because I thought it unseemly for a man with my combat record to serve under a man who had never heard a gun go off.” But Patton did so because he was a good soldier.

After attending a lunch hosted by Bedell Smith for the new chief of U.S. Army forces in Europe, Patton waxed indignant. “I have rarely seen assembled a greater bunch of sons of bitches,” he wrote in his diary. “The whole luncheon party reminded me of a meeting of the Rotary Club in Hawaii where everyone slaps everyone else’s back while looking for an appropriate place to thrust the knife. I admit I was guilty of this practice, although at the moment I have no appropriate weapon.”

Patton also groused that, because he had been in and out of the doghouse, he had not received sufficient recognition for his war service. “I got nothing for Tunisia, nothing for Sicily, and nothing for the Bulge,” he noted. “Brad (General Omar Bradley) and Courtney (General Courtney Hodges) were both decorated for their failures in that operation.”

Patton’s numerous decorations, in fact, included the Distinguished Service Cross with Oakleaf Cluster, the Distinguished Service Medal with two clusters, the Silver Star with cluster, the Legion of Merit, Knight of the British Empire, the French Legion of Honor, and the French Croix de Guerre.

As Patton lapsed deeper into a bitter mood, his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Hobart R. “Hap” Gay, became increasingly concerned. The torment of his longtime friend and boss hurt him, so he cast around for some diversion that would cheer him up. A pheasant hunt might do the trick, he decided. On the evening of Saturday, December 8, Gay casually suggested that they would find “some good hunting” in a game-rich area west of the River Rhine city of Speyer, a few miles south of Mannheim. Patton brightened up and replied, “Yes, let’s do it.” They agreed to go on the following day, just before Patton’s scheduled flight to England and homeward voyage on December 10.

Around 9 AM on the clear, cold morning of Sunday, Dec. 9, 1945, the two generals left Bad Nauheim in Patton’s elegant 1938 Model 75 Cadillac limousine, driven by Pfc. Horace L. Woodring. He had chauffeured Patton for four months following the departure of Sergeant Mims. The car was trailed by a jeep driven by Technical Sergeant Joe Spruce, which carried the generals’ rifles and a hunting dog. The two vehicles rolled along the Kassel-Frankfurt-Mannheim autobahn and then made a detour near Bad Homburg to enable Patton to visit the ruins of a Roman fort in the nearby Taunus Mountains. He got his boots and socks soaked while tramping around in the snow.

The vehicles then headed along National Route 38 toward the northern outskirts of Mannheim, with Patton trying to dry himself out in the Cadillac. He had ordered the hunting dog transferred to the car because he was afraid that it would freeze to death in the jeep. Around 11 AM, the vehicles were flagged down at a military police checkpoint, and a young soldier demanded that the occupants identify themselves. Patton jumped out of his car, patted the shivering MP on the back, and told him, “You are a good soldier, son. I’ll see to it that your CO is told what a fine MP you make.”

In the northern Mannheim suburb of Kafertal, Woodring slowed the Cadillac down and then halted at a crossing while a train passed. When the gates were raised, the limousine crossed the tracks and sped up to about 30 miles an hour. Sergeant Spruce’s jeep was now leading, because Woodring did not know the way to the hunting grounds.

At about 11:45 that morning, the hunting trip came to an abrupt and fateful end. An approaching, slow-moving two-and-half-ton truck driven by Technician 5 Robert L. Thompson, about to enter a nearby quartermaster depot, suddenly turned left in front of the Cadillac. He gave no signal, according to Sergeant Woodring and General Gay. Woodring slammed on the brakes and veered left, but the two vehicles collided. The front end of the limousine was crushed.

The two drivers and Gay suffered only cuts and bruises, but Patton was thrown forward awkwardly into the Cadillac’s overhead ceiling light and steel-and-glass partition. His nose and neck were broken, most of his scalp was peeled from his head, and his spinal cord was damaged. He was bleeding profusely and unable to move, yet conscious.

The Army’s 130th Station Hospital in Heidelberg, 25 miles away, was alerted by radio, and Patton was rushed there by ambulance. Carried in on a litter about an hour after the accident, he was given blood plasma, penicillin, and a tetanus shot. Showing some improvement at once, the stricken general opened his eyes and grumbled something. When a doctor asked what he wanted, he chuckled, “Relax, gentlemen, I’m in no condition to be a terror now.” A few minutes later, he said, “Jesus Christ, what a way to start a leave.” The hospital chaplain offered prayers, and Patton thanked him. Within two hours, 11 concerned generals were at the hospital, including his good friend and longtime cavalry comrade, Lt. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes.

Surgeons x-rayed Patton, sutured his scalp wound, gave him more plasma, and placed him in traction. His condition was grave, so telephone calls went out to Washington, and two British Army neurosurgeons were summoned to help assess his wounds. Also at the hospital were about 30 correspondents, many of whom had been covering the Nuremberg war trials.

When the U.S. surgeon general notified Beatrice Patton of her husband’s accident, General Eisenhower made a C-54 Skymaster transport plane available to her. She was accompanied by Colonel R. Glen Spurling, an Army neurosurgeon. Because of severe storms all over Europe, it was a grueling journey, but Spurling said that Mrs. Patton’s personality radiated “like a brilliant gem.“ After flying by way of Newfoundland, the Azores, and Marseilles, she arrived at the Heidelberg hospital on the afternoon of December 10.

Colonel Spurling hastened to Patton’s bedside, where the general cheerfully apologized “for getting you out on this wild goose chase.” Spurling agreed with the American and British doctors that nothing further could be done. An operation was out of the question, and all that Patton could hope for was semi-invalidism. He would never be able to ride a horse again. “Thank you, colonel, for being honest,” he said gravely. “I’ll try to be a good patient.”

The feisty warrior was out of action, but far from forgotten. Newspapers and radio broadcasts were full of reports of his accident and condition, and letters, telegrams, and cards poured into the hospital from veterans’ groups, mayors of French villages, a nun, and black GIs. Patton was particularly cheered when his nurse read him a get-well message from President Harry S. Truman, while a letter from Eisenhower read, “You are never out of my thoughts and … my hopes are tied up in your speedy recovery.”

Friends clamored to see Patton, and more than 50 British officers and soldiers inquired about his condition. Through the ordeal, Beatrice Patton was attentive, composed, and hopeful. She was “as plucky and courageous as five people,” reported General Keyes.

As the days passed, Patton was out of danger and seemed to be improving, but the degree of recovery was unsettled. The doctors were initially optimistic but eventually held out little hope, and his improvement ceased by the end of the third day. His appetite lessened, he coughed a lot, and he grew weaker. Lingering bravely for 13 days, Patton was immobile and helpless but tried to be alert and jovial with visitors. Alone with his nurse, he was depressed.

The general took a sudden turn for the worse on the night of December 20, and the hospital announced on the following day that his condition was serious. Patton told his nurse several times that day that he was going to die. Beatrice spent most of the afternoon of December 21 reading to her husband, after which he dozed off and never woke up. He died at 5:55 PM of “pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure.” Colonel Spurling reported, “Patton died as he had lived—bravely. Throughout his illness, there was never one word of complaint regarding a nurse or doctor or orderly. Each and every one was treated with the kindest consideration … He was a model patient.”

Heidelberg became unusually quiet, all service clubs were closed, and flags were lowered to half-staff all over Germany. Beatrice discussed her husband’s burial with Keyes and Spurling and decided on the sprawling American Cemetery at Hamm, a Luxembourg City suburb, where many Third Army fallen had been laid.

More cards, letters, and telegrams poured into Heidelberg—from politicians and statesmen, including Truman and British Prime Minister Clement Attlee; from soldiers who had served with Patton; and from the French National Assembly. General Bradley cabled his condolences.

Patton’s body lay in state in the mountaintop Villa Reiner overlooking Heidelberg on Saturday, December 22, and on the following cold, dismal afternoon, his coffin was sealed and escorted by a 15th Cavalry Regiment platoon and pallbearers in jeeps and scout cars to the city’s Christ Church. Veiled in black, Mrs. Patton came accompanied by General Keyes and a tearful General Truscott.

Dozens of generals led by McNarney filed from the villa to the church, where two Army chaplains conducted a 22-minute Episcopalian service. Flowers surrounded the flag-draped coffin, and the rite was attended by delegations from Great Britain, France, Sweden, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Soviet Union, and the major U.S. commands in Europe. The chaplains recited Patton’s two favorite psalms, the 63rd and 90th, and a 36-voice soldier’s chorus sang the old Anglican hymn, “The Strife Is O’er.”

While the bands of several divisions played following the end of the service, the general’s coffin was loaded aboard a Third Army half-track and solemnly escorted to the railway station a mile away, where two trains waited. Six thousand shivering GIs lined the streets.

At the station, a 1st Armored Division artillery battery fired a 17-gun salute before the coffin and thousands of flowers were loaded into the baggage car of the lead train. Accompanied by Generals Keyes, Gay, and Truscott, Beatrice Patton rode with the coffin while the rest of the mourners sat in the second train. The trains rolled out of Heidelberg at 4:30 PM on the lengthy journey to Luxembourg. Passing briefly through France, six halts were made so that Mrs. Patton could inspect honor guards and receive more wreaths. The trains arrived in Luxembourg City late on the rainy night of December 23.

The morning of Christmas Eve was rainy, windy, and dreary as Patton’s coffin was loaded onto a halftrack for the half-hour procession to the cemetery. Master Sergeant William G. Meeks, the general’s trusty, longtime Black driver, drove the vehicle. The road was lined for three miles by U.S., French, Belgian, and Luxembourgian troops.

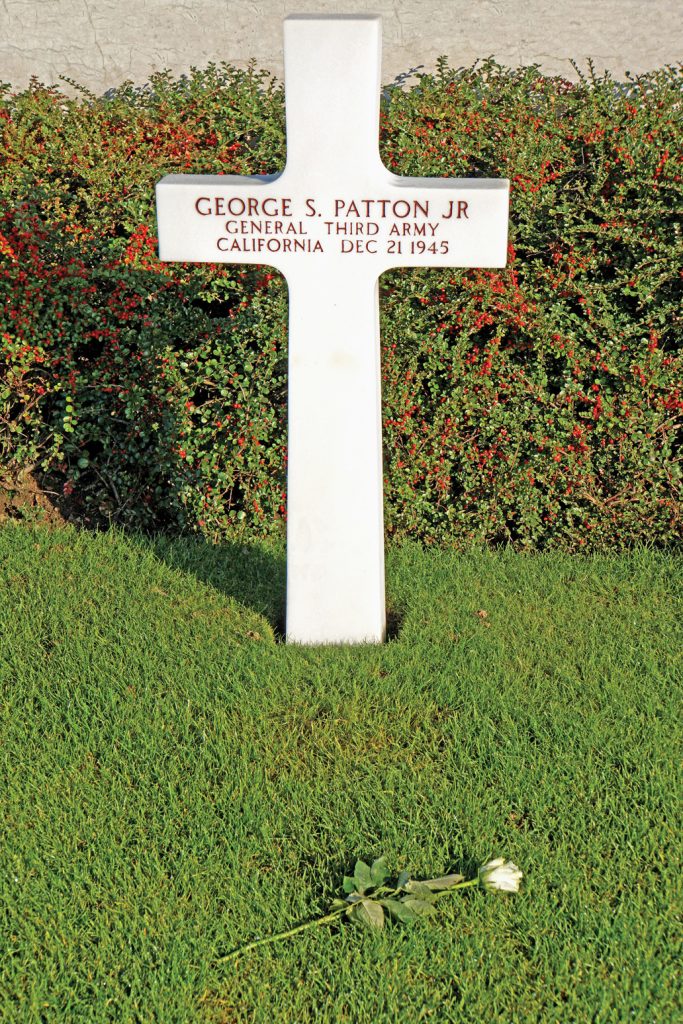

General Patton was buried during a poignant, 25-minute ceremony at mid-morning while shivering generals, enlisted men, Luxembourgers, and correspondents watched. The focal figure was Beatrice Patton, grief-stricken but stoic. “Her eyes were red, but for the rest, she was the same good soldier her husband had been,” reported Walter Cronkite for the Washington Times-Herald. The tearful Meeks bowed and handed her the flag, which had draped the coffin; then a 12-man squad fired a three-round volley of salutes, and a bugler sounded taps. A simple white cross was later placed over the grave.

“History has reached out and embraced General George Patton,” said a New York Times editorial on December 22, 1945. “His place is secure. He will be ranked in the forefront of America’s great military leaders.” Of several memorial services arranged, the most impressive was conducted in the Washington Cathedral on January 20, 1946. Twelve hundred mourners, including former Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, one of Patton’s longtime benefactors, and General Eisenhower, attended.

Patton soon became a folk hero in the tradition of Daniel Boone, Buffalo Bill, and Sergeant Alvin C. York. Published in 1947, his memoir was a bestseller, and buildings, streets, squares, and parks were named for him in both Europe and the United States. He was remembered with numerous plaques and busts, a museum at Fort Knox, Kentucky, a stained-glass window at the Anglican Church of Our Savior in San Gabriel, California, and a bronze statue facing the library at the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York.

While Patton was feared and respected by his men, he was not loved in the way that American Generals James M. Gavin and William O. Darby, or British Generals William Slim and Brian Horrocks, were loved. Many a GI groused, “Old Blood and Guts? Sure, our blood and his guts.” In North Africa, Sicily, and Europe, though, Patton proved to be a master at instilling discipline and fighting spirit in green citizen soldiers. Every veteran of the Third Army was proud to say that he served under him.

As a tactician, Patton sometimes proved first-rate and sometimes average, but his use of weapons and air support was probably unequaled. “He knew the value of combined arms,” said U.S. Army historian Hugh Cole, “and he had a cavalryman’s eye for ground.” He was an outstanding trainer and tactical innovator. When war came, he was one of the few American commanders prepared to fight the Germans. “Patton,” wrote British biographer Hubert Essame, “was unquestionably the outstanding exponent of armored warfare produced by the Allies in the Second World War.”

The image that Patton rehearsed and fostered was that of a fierce swashbuckler who relished war. “He liked to fight. He’d rather fight than eat,” observed General Paul Harkins. Yet he was affected often by death and suffering and was not a warmonger. Major General Isaac D. White, who commanded the 2nd Armored (“Hell on Wheels”) Division early in 1945, said, “He loved the opportunity that war presented to use the skill, the leadership, and the courage his profession required, as a surgeon loves his profession, but not disease, illness, and injury.”

Author Michael D. Hull wrote extensively for WWII History for many years and resided in Enfield, Connecticut.