By Christopher Miskimon

The meeting room was freezing cold on December 19, 1944, despite the small stove in the corner. It was in northern France during one of Europe’s coldest winters in memory. There were 16 officers in the room, four British and twelve American. They kept their coats on to stay warmer and smoked cigarettes, pipes, and cigars, filling the room with smoke. A large map covered one wall with rows of wooden folding chairs lined up before it.

One of the cigars smokers was General George S. Patton, Jr. He paced the room, concerned about the reports he had been reading about German penetrations in the Ardennes. Outwardly he feigned a cheerful attitude, but Patton worried about Allied setbacks and the weather that kept their air forces from flying.

One of the cigars smokers was General George S. Patton, Jr. He paced the room, concerned about the reports he had been reading about German penetrations in the Ardennes. Outwardly he feigned a cheerful attitude, but Patton worried about Allied setbacks and the weather that kept their air forces from flying.

Patton’s superior, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, seemed in a genuinely better mood. He started the meeting by stating definitively, “The present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity for us and not disaster. There will be only happy faces at this conference table.” The good attitude bolstered Patton’s outlook. He said, “Hell, let’s have the guts to let the bastards go all the way up to Paris. Then we’ll really cut ‘‘em off and chew ‘em up!” It broke the tension in the room, though Eisenhower reminded everyone the Germans could not be allowed to cross the Meuse River.

The meeting turned to a discussion of how best to engage the attacking Germans and defeat them. Shortly the group realized their best idea was to have Patton turn part of his army north and counterattack into the German southern flank. Other commanders would take over responsibility for the section of the front Patton had to vacate to turn part of his Third Army.

Patton was initially quiet, though he did say he needed replacements for his infantry casualties. Finally, Eisenhower said, “George, you’re going to have to abandon your plan to break free of the Siegfried Line and attack north. I want you to go to Luxembourg and take charge.” Patton replied simply, “Yes sir.” When Patton was asked how long it would take for him to pivot and attack, some say he said 48 hours—December 21—while others thought he said the 22nd. Many in the room didn’t believe he could turn that fast, though a few seemed excited at the prospect. A few of the British officers laughed. Patton reportedly followed by stating, “I can put on a spoiling attack with three divisions in three days or a more concentrated attack by six divisions in six days.”

General Omar Bradley, Patton’s direct superior, wasn’t surprised by the statement; Patton had mentioned it the night before. He was alarmed at how quickly Patton was claiming he could do it. When Bradley asked Patton how feasible the plan was, Patton replied, “Brad, this time the Kraut’s got his head in a meatgrinder.” Patton symbolically closed his hand into a fist. “And this time I’ve got hold of the handle.”

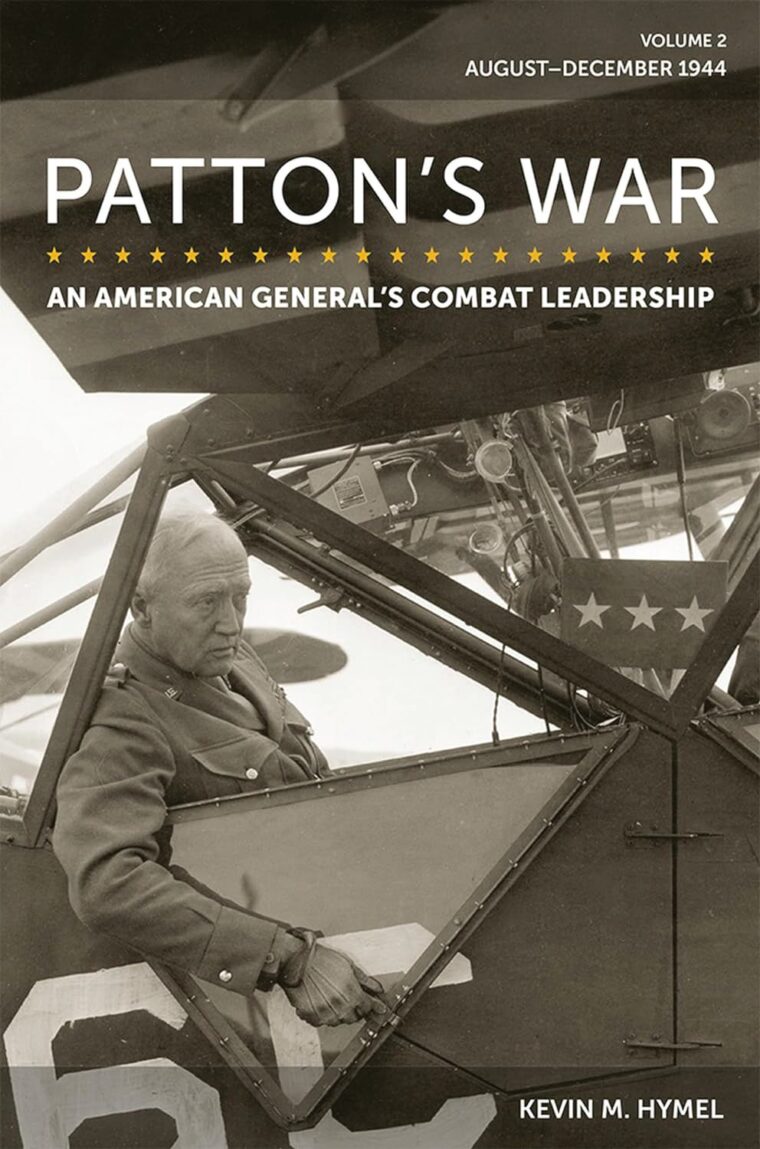

Though no one doubts his ability to command an army in the field, George S. Patton is a controversial figure. He cared for his men and tried to see to their needs, but he also slapped two of them in a hospital in Sicily. Many admired his leadership ability, but he could be a harsh bully to his subordinates. Patton was a man of contradictions, but he was also someone who could thrive in the terrible conditions of war and achieve success. The reader can see Patton at the height of his generalship in Patton’s War: An American General’s Combat Leadership, Volume 2 August-December 1944 (Kevin M. Hymel, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO, 2023, 467 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover).

So much has been written about Patton it would seem there is nothing new to be discovered, but the author has succeeded in this task. Previous scholars have used Patton’s transcribed diaries, which are heavily edited. This book benefits from the author’s use of the general’s original handwritten diaries to rediscover lost information. This volume focuses on Patton at his best, after his troubles in Sicily and before his late- and postwar difficulties. He was a field commander and this book lets the reader see him in that way, strengths and flaws together.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments