By William E. Welsh

Lieutenant General George Patton’s Third Army had come a long way since it was activated on August 1 in Normandy. Following the breakout from Normandy in late July, Patton’s army had swept 400 miles in one month’s time all across central France to the Lorraine region, where it was met by General der Panzertruppen Otto Knobelsdorff’s First Army, which was determined to defend the Moselle line.

Nevertheless, the XII Corps under Maj. Gen. Manton Eddy on Patton’s right, or southern, wing, was able to cross the Moselle and concentrate at Arracourt, while his other corps, the XX Corps, under Maj. Gen. Walton Walker, aimed directly for Metz.

Reinforced by General der Panzertruppen Hasso von Manteuffel’s 5th Panzer Army in the middle of the month, Knobelsdorff’s First Army was in a position to launch a major counterattack against Eddy’s XII Corps bridgehead. A surprise attack against Eddy’s right flank at Lunéville on September 18 marked the beginning of a protracted 11-day tank battle in which German forces tried unsuccessfully to isolate and destroy Eddy’s bridgehead on the east bank of the Moselle.

Throughout the course of the Battle of Arracourt, the Germans were constantly forced to scale back their objectives when the Americans successfully parried one blow after another. During the fighting, Maj. Gen. John Wood’s 4th Armored Division––dubbed “Patton’s Best” by its members and “Roosevelt’s Butchers” by the enemy––was able to inflict heavy losses on German panzer units.

The fighting fizzled out when German Führer Adolf Hitler transferred Manteuffel’s Fifth Army north at the end of the month to counter the Allies’ moves against the West Wall, as well as part of preparations for a planned winter attack through the Ardennes.

Patton on the Defensive

On September 25 12th Army Group commander Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley had ordered Patton to go on the defensive so that precious fuel reserves could be channeled to Allied forces engaged in Operation Market Garden, a major operation designed to capture key bridges in Holland. The shortage of fuel meant that Patton was unable to follow up his victory at Arracourt with a counterstroke that might have allowed his troops to reach the West Wall before the onset of bad weather.

Loud grumbling from Patton could do nothing to change the situation. Still, the Third Army’s commander was too impatient to sit idly by with German forces within striking distance. At the end of September 1944 fuel wasn’t the only commodity in short supply for the Third Army. Patton’s men also lacked howitzer ammunition, rain gear, blankets, and sufficient rations. Morale dipped as a result, and Patton set about finding a way to keep his troops in the fight––regardless of the dismal supply situation.

As soon as Patton received the official word that he was to take a defensive stance, he submitted to Bradley a plan he had drawn up that he hoped would enable him to continue limited offensive operations. “The whole plan was based … on maintaining the offensive spirit of the troops by attacking at various points whenever my means permitted it,” Patton wrote in his memoirs. In addition to keeping his various units in fighting trim, these limited attacks were meant to adjust the Army’s line in key places so as to give the units favorable departure points for resuming full-scale offensive operations once more fuel became available.

While Eddy’s XII Corps units had firmly established themselves to a depth of 15 to 20 miles on the east bank of the Moselle, the one division of Maj. Gen. Walton Walker’s XX Corps that had managed to cross the Moselle just south of Metz in September remained in a precarious position. Maj. Gen. Leroy Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division had crossed at Arnaville on September 10, but since then had been contained by the veteran 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division in fortified positions atop high ground to the east.

The continuing reorganization of Allied forces on the Western Front left Patton with four veteran infantry and two armored divisions with which to prosecute his limited attacks in early October. Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip’s XV Corps was reassigned to Lt. Gen. Jacob Devers’s Sixth Army Group, which lay to the Third Army’s south, while the 7th Armored Division was transferred from Walker to Lt. Gen. William Simpson’s Ninth Army. In return, Patton was promised three new divisions between mid-October and the first week of November.

The German Order of Battle at Metz

The main German force responsible for holding Metz was Knobelsdorff’s First Army, which belonged to General der Panzertruppen Hermann Balck’s Army Group G; Balck kept a close hand in the First Army’s operations. The German First Army had lost the cream of its forces after September. The crack 3rd and 15th Panzergrenadier Divisions were transferred north as part of the assembly of elite units to counter Allied moves against the West Wall (and, as mentioned, to prepare for Hitler’s coming winter offensive that would be known as the Battle of the Bulge). Another unit, the veteran 553rd Volksgrenadier Division, was sent south to join the Ninteenth Army. Of the First Army’s nine divisions, only four had offensive capabilities. The other five, because of a lack of equipment and experience, were capable only of static defense.

Knobelsdorff’s First Army forces comprised the 11th Panzer and 17th SS Panzer-grenadier Divisions, the 48th and 416th Divisions, the Luftwaffe 9th Flak Division, and the 19th, 361st, 462nd, and 559th Volksgrenadier Divisions. The 416th Division and the 19th and 361st Volksgrenadier Divisions would begin arriving in the sector in October but were pitiful substitutes for the troops they were meant to replace.

Balck’s reserve consisted only of Generalleutnant Wend Wiethersheim’s 11th Panzer Division. Wiethersheim enjoyed the distinction of being the only commander in the string of battles fought in September to seriously threaten the Americans. Having lost nearly all his armor in the September fighting, Wiethersheim had pleaded for more tanks and by the beginning of November had an armored force consisting of 60 Panthers and Mark IVs and 10 tank destroyers with which to counter Third Army breakthroughs in the German battle line.

In the north, on the German right flank, was stationed the untested 416th Division, which consisted of middle-aged garrison troops from Denmark led by Generalleutnant Kurt Pflieger. Directly opposite Thionville, and in supporting distance of the Metz garrison, was Oberst Karl Britzelmayr’s 19th Volksgrenadier Division, which had seen combat and had enough field artillery to be reasonably effective in static defense. Generalleutnant Vollrath Luebbe’s 462nd Volksgrenadier Division manned the Metz fortifications and General der Waffen-SS Werner Ostendorff’s 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division held the ground immediately south of the city. Generalleutnant Carl Caspar’s 48th Division, the smallest and weakest unit in the First Army, was stationed south of the Panzergrenadiers.

The hilly forests and valleys east of Nancy were defended by General Major Kurt Freiherr Muehlen’s 559th Volksgrenadier Division. Farther south, Oberst Alfred Philippi’s 361st Volksgrenadier Division––a hodgepodge of sailors and Luftwaffe support personnel inexperienced in ground combat—anchored the German left flank.

The 9th Flak Division supported the First Army’s left flank, and Wiethersheim’s 11th Panzer Division was positioned about 15 miles behind the main line in the center near Saint Avold, where it could respond quickly to any threat along the 60-mile front.

The 43 Forts of Metz

Although Eddy’s XII Corps on Patton’s right flank launched an attack on October 8 to correct its line and establish a bridgehead on the east bank of the Seille River in preparation for the pending full-scale offensive, the two bloodiest local attacks during October were carried out by Walker’s XX Corps on the west bank of the Moselle––one north of Metz at the industrial town of Maizieres-les-Metz and one south of it at Fort Driant.

Fort Driant, which was part of the chain of forts at Metz on the west bank of the Moselle guarding the approach from that direction, was the primary objective of a limited attack assigned to troops from Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division. Until Driant’s five batteries were silenced, it would be impossible for Patton’s infantry to move up the Moselle River along the east bank and attack the city itself.

The very large thorn in the Third Army’s side was the sprawling Metz fortress system whose octopus-like tentacles spread six miles west of the Moselle and reached back another four miles to the east of the old Gallo-Roman city. The massive system, which made Metz the most heavily fortified city in Europe at the time, consisted of 43 forts arrayed in an inner and outer belt that together mounted 128 heavy guns. Artillery fired from strategic forts in the outer belt had wreaked havoc on attempts by Walker’s infantry divisions to cross the Moselle above and below the city during September.

The forts in the outer belt were situated in close proximity to each other so as to provide mutual support. The two most formidable forts on the west bank were named “Driant” and “Jeanne D’Arc.” In those and other modern forts in the complex, the guns were housed in revolving steel turrets and their crews and the rest of the garrison protected in subterranean quarters surrounded by dry moats and multiple rows of barbed wire designed to make a direct assault against the fort a costly endeavor.

Back in September, and going by faulty intelligence indicating that the fort was thinly held, Colonel Charles Yuill, commanding the 5th Division’s 11th Infantry Regiment, drafted a plan of attack that, although opposed by Irwin, nevertheless received a stamp of approval from Walker and Patton.

The Fight For Fort Driant

Driant was one of the strongest and most modern forts in the outer belt surrounding Metz. It was situated five miles southwest of Metz on the west bank of the Moselle atop a 1,200-foot hill and surrounded by rows of barbed wire on the outer perimeter and within by a dry moat 60 feet wide and 30 feet deep meant to impede infantry and tracked vehicles. Although its 100mm and 150mm guns were mounted in turrets visible above ground, the bunkers and the central fort were located underground and linked by a network of tunnels, all of which was protected by a 15-foot-thick roof of reinforced concrete.

On the morning of September 27, P-47 Thunderbolts swooped low over the fort and dropped 1,000-pound bombs and napalm canisters on the trenches at the base of the fort and on the structure itself. That afternoon, Yuill’s 2nd Battalion, with the support of a company of tank destroyers, attacked from two directions but made no headway against enemy pillboxes leading up to the fort. The following day no additional progress was made, and the attack was broken off.

Despite the repulse, Patton was unwilling to call off the attack so quickly. “We have put our hands to the plow; we must finish the job,” he told Walker.

Fresh tactics were devised. When Yiull’s men attacked again five days later on October 3, they were armed with Bangalore torpedoes and satchel charges. One company managed to gain a toehold on the southwest section of the fort’s roof, which it precariously held for two days. However, repeated enemy sorties from underground bunkers disrupted the demolition work and threatened to isolate Yuill’s forward detachments. What’s more, the Germans began shelling the American positions at Fort Driant from neighboring forts.

A chilling situation report written October 4 by Captain Jack Gerrie from his position at the deepest penetration of the fort was carried by messenger back to his superiors: “The situation is critical. A couple more barrages and a counterattack and we are sunk. We have no men, our equipment is shot, and we just can’t go on. The enemy artillery [from adjacent forts] is butchering these troops and we have nothing else to hold.”

Irwin broke off the attack the following day and replaced elements of his battered 11th Infantry with fresh troops from his 2nd and 10th Regiments; the two units renewed the assault on October 7. This time, the Americans attempted to fight their way into the underground entrances to the fort but made no better progress; they soon were bogged down.

After days of heavy fighting, during which American losses mounted, Patton reluctantly issued orders for the troops to break off the fight. On the night of October 12, the last of the troops were withdrawn from around Fort Driant. It was a significant tactical defeat for Patton’s Third Army, which had nothing to show for the 800 casualties suffered by Irwin’s division. Still, lessons learned in fortress fighting would be applied the following month.

Planning a Two-Pronged Attack

While the men of Irwin’s “Red Diamond” division had been fighting a losing battle to capture Driant, Maj. Gen. Raymond McLain’s 90th Division was engaged in trying to clear the Germans from their entrenched positions in Maizieres-les-Metz, a factory town on the west bank of the Moselle five miles northwest of Metz. If McLain’s forces could capture the town, it would give them a strong position on the right flank of the German forces still occupying the outer string of forts on the west bank of the Moselle.

On October 7, the 2nd Battalion of Colonel George Barth’s 357th Infantry Regiment, 90th Division, had attacked the town from the west and north. Realizing the threat the Americans posed, Balck sent an additional regiment into the town that helped stop the assault. Patton, who craved fast-moving offensives, was frustrated by the inertia that had been imposed upon his army at Metz because of enemy resistance and the lack of fuel.

Meanwhile, on October 10, after it was learned that Operation Market Garden had ended in failure for the Allies, Bradley summoned his generals to Verdun to set the wheels in motion for a new allied offensive against the Germans.

Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force General Dwight D. Eisenhower and his staff envisioned for fall 1944 a two-pronged offensive to capture the Ruhr and Saar industrial regions that fed the Third Reich’s belly. General Courtney Hodges’s First Army and General Allen Simpson’s Ninth Army would lead the primary attack against the larger Ruhr in the north, while in the south General George Patton’s Third Army would strike at the smaller Saar. Although no firm date was set for when the offensive would begin, Bradley tasked his subordinates with crafting detailed plans for their respective sectors. It was just what Patton had been itching for.

Bradley arranged for Patton to receive three fresh, untested divisions for the upcoming offensive. The first of these due to arrive in the Third Army’s sector was Maj. Gen. Willard Paul’s 26th Infantry Division, which took up its position on Eddy’s right flank on October 12. Walker’s corps would receive the other two new divisions; the 95th Infantry Division, led by Maj. Gen. Harry Twaddle, would begin arriving in the XX Corps sector on October 18, where it was to help contain German forces in the western portion of the Metz fortress complex. To compensate for the earlier transfer of the 7th Armored Division, Walker received Maj. Gen. William Morris’s 10th Armored Division, which did not take up its place on Walker’s left flank until November 2.

House-to-House Fighting in Metz

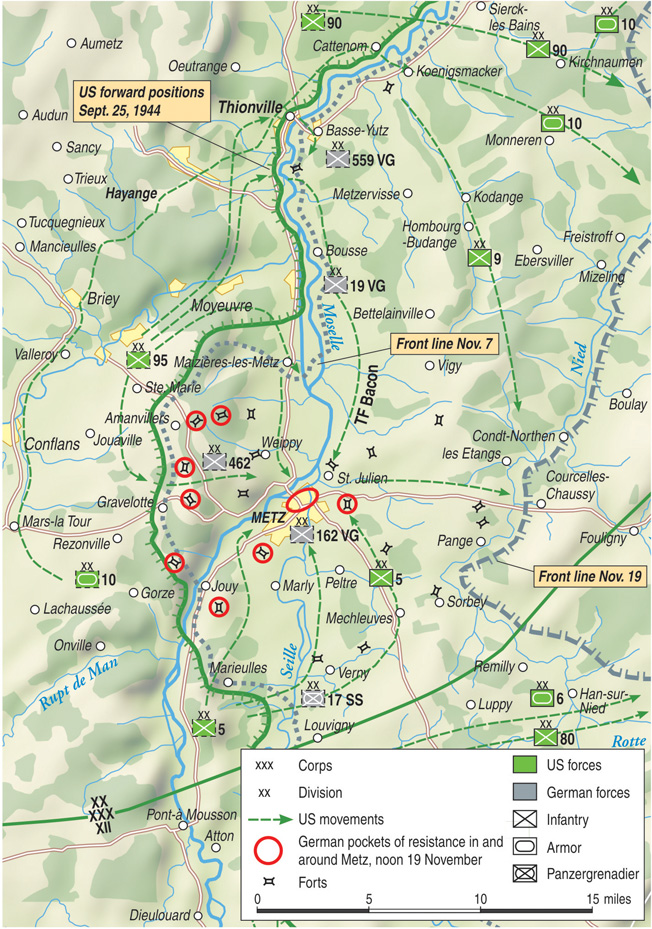

On October 14, Patton and his corps commanders began to draft the Third Army’s plan of attack. The final plan submitted to Bradley called for a double envelopment of Metz by the XX Corps on the Third Army’s left flank, in which the 90th Infantry Division, supported by Maj. Gen. William Morris’s 10th Armored Division, would form the northern pincer and Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division would form the southern pincer. Lead elements of the two infantry divisions were to rendezvous east of Metz in the general vicinity of Boulay-Moselle. The double envelopment was intended to bring about the fall of Metz by cutting the supply routes into the city “without getting mixed up with the forts,” Patton said.

Town fighting proved just as hard. Inside Maizieres-les-Metz, the battle seesawed back and forth for a week, then longer. On October 15, command of the 90th passed from McLain to his replacement, Maj. Gen. James Van Fleet, who pushed the 357th to complete its mission.

The enemy fortified the town’s buildings using sandbags and barbed wire. The ensuing house-to-house fighting gave the soldiers of the 357th a chance to hone their fortress-fighting skills. In situations where the Americans occupied one room of a building and the Germans an adjacent one, the Americans would stuff rags into five-gallon gasoline cans, ignite the contraption, and hurl it into the enemy-occupied room.

In the center of the city, the Germans transformed the sturdy Hotel de Ville (city hall) into a miniature fortress impervious to light anti-tank weapons. On October 20, the Americans brought forward a 150mm howitzer to pound enemy forces inside the building.

The fighting surged back and forth around the city hall for an entire week. When the Americans finally fought their way into the building on October 26, they were driven off by enemy troops armed with flamethrowers. Colonel Barth then ordered his troops to bypass the position and focus on clearing the rest of the town instead. After Barth’s infantry pulled back from the city hall, the building was pulverized by 240mm howitzers firing from outside the city. On the 30th, Barth reported to his superiors that Maizieres-les-Metz was finally in American hands.

Pushing For the West Wall

While Walker’s troops focused on reducing and capturing Metz, Eddy’s XII Corps began the arduous task of slowly driving the Germans east toward the West Wall. After Eddy’s three infantry divisions established bridgeheads on the east bank of the Seille on the first day, Wood’s 4th Armored Division and Maj. Gen. Robert Grow’s 6th Armored Division would pass through the XXI Corps infantry on the right and left flanks, respectively. The plan called for Grow to cover Irwin’s right flank and for Wood to push toward the Saar River and secure a crossing south of Saaregemund in preparation for a later attack on the West Wall.

Bradley initially intended for Hodges’s First Army to attack toward the Ruhr in late October, and Patton’s Third Army to renew its attack toward the West Wall and the Saar region after Hodges. When it became clear to Bradley that Hodges would not be ready to attack in that time frame, Bradley turned to Patton. When asked how soon he could move, Patton replied that he could attack as soon as November 8, and perhaps earlier if the weather permitted.

Patton was counting heavily on the Air Force for support in the coming campaign to soften up the enemy’s fortifications and frontline positions prior to his troops shoving off. When Patton met with Brig. Gen. Otto Weyland on November 2, he designated the Metz fortress and the Delme Ridge opposite Eddy’s left flank as primary targets for air strikes. However, commitments to other sectors prevented the XIX Tactical Air Command, led by Weyland, from providing the Third Army with the same level of support it had received from the command in August and September. Whereas the XIX TAC flew 12,000 sorties in support of the Third Army in August, it would only able to carry out 3,500 during November.

The Eve of Patton’s Offensive

On the eve of the offensive, Patton’s Third Army had a three-to-one advantage in troop strength over Knobelsdorff’s First Army. Patton’s army had 250,000 men, while the First Army had about 86,000. The Third Army also had a decisive advantage in all types of equipment, including tanks, artillery, and support vehicles. However, Third Army was hampered by an acute shortage of fuel and ammunition.

Although the fuel situation was remedied before the offensive began, the ammunition shortage was never resolved. The Third Army had learned early in the Lorraine fighting to make good use of captured artillery and ammunition when the opportunity presented itself. Eddy’s three infantry divisions were deployed forward over a 30-mile front. Maj. Gen. Horace McBride’s 80th Division was on the left, Maj. Gen. Paul Baade’s 35th Division in the center, and Maj. Gen. Willard Paul’s 26th Division on the right. Behind them, two armored divisions waited to assume the lead once bridgeheads were established over the Seille River.

Once the fuel began to arrive at the railhead in Nancy during the first week of November, the only thing holding the Third Army back was the inclement weather. Heavy rains transformed fields into quagmires, swept bridges off their moorings, and made existence miserable for GIs who lacked the most basic foul-weather gear. Shortages of galoshes and waterproof shoepacs caused an epidemic of trench foot.

Patton spent the first few days of November on the eve of the attack driving through torrential downpours from one division to the next, where he addressed officers and noncoms. Although some veteran units had heard his rousing, eve-of-battle speeches before, like the new troops hearing it for the first time they drank it up like a refreshing beverage. Patton invoked God’s will and power for the Allies’ virtuous cause and, in the same breath, spat and cursed the Huns as bastards deserving the horrible ends they would meet at the hands of his troops.

The weather did everything it could to foil Third Army’s plans. Continuous rains the following two days led Patton to postpone the attack, but he resolved on November 7 that the attack would go forward the following day whether or not the rain stopped, and his staff issued orders to Eddy’s XII Corps to prepare to attack the following morning. Anticipating a Third Army offensive, Hitler issued orders that same day that the garrison in Metz was to fight to the last man.

The terrain through which the XII Corps would attack favored the Germans. After the American infantry had bridged the Seille, it would have to drive the Germans from heavily forested ridges and plateaus that lay astride the only two main roads that led northeast toward the Saar. The infantry’s primary job would be clearing the enemy from dugouts and bunkers along the ridges, while the armor would deal with enemy road blocks and strong points on the primary and secondary roads.

McBride’s initial objective on the left flank was to clear the Germans from the Delme Ridge and then support Grow’s 6th Armored in its push to the important crossroads of Faulquemont, situated 20 miles away. In the center, Baade would have to pry the Germans from the Forest of Chateau-Salins on the Morhange plateau and assist Combat Command A of Wood’s 4th Armored Division in clearing the road from Chateau-Salins to Morhange. On the XII Corps’ right flank, Paul would need to clear the Germans from the heavily wooded Dieuze plateau, thereby outflanking the strong enemy garrison in the town of Dieuze astride the Moyenvic-Mittersheim road.

“I Hope They Killed a Lot of Generals”

As if in defiance of the foul weather, 37 battalions of field artillery supporting Eddy’s XII Corps opened fire on German positions beyond the Seille in the predawn hours of November 8. More than 30,000 rounds screamed down on enemy batteries, command posts, and assembly points in preparation for the infantry assault, which began at first light of day. As if on cue, the skies temporarily cleared, and the infantry regiments jumped off toward their objectives. Overhead, P-47s streaked east to plaster enemy troop concentrations and headquarters with their potent combination of rockets and bombs. “I hope,” Patton wrote to his wife, “they killed a lot of generals.”

The Germans, believing that the muddy conditions of the landscape prevented a front-wide attack by the Americans, had grown complacent in the previous fortnight and were taken by surprise by Eddy’s assault. On Eddy’s right flank, Paul’s 26th Division easily captured the Seille crossing at Moyenvic, but was stopped cold for 72 hours by elements of Philippi’s 361st Volksgrenadier Division, backed by mortars and howitzers, atop Hill 310 at the western end of the Dieuze plateau.

Elsewhere along the XII Corps front the fighting went better and, by the end of the day, enough Seille crossings were in friendly hands to enable Eddy to order his two armored divisions to pass through the infantry on the second day of battle.

Crossing the Flooded Moselle

On Patton’s left wing opposite Metz, the fighting unfolded more slowly because of the difficulties encountered trying to cross the flooded Moselle. Patton had directed that the XX Corps’ attack begin on November 9, one day after Eddy’s attack on the right.

Van Fleet’s 90th Infantry Division was under orders to cross the Moselle 23 miles north of Metz and begin a wide envelopment of the city from the north. Two locations, Cattenom and Malling, were chosen as the crossing points for the 358th and 359th Regiments, respectively.

The 357th, which followed after the bridgehead was secured, was under orders to push south along a forested ridge, clearing the enemy from 19 lightly defended Maginot forts. The 359th was to protect the division’s left flank against German counterattacks, while the 358th was to clear the enemy from several forts guarding the east bank of the Moselle, the most imposing of which was Königsmacker, opposite Cattenom. The division’s ultimate objective was to push 16 miles south through enemy-infested territory and link up with Irwin’s 5th Division.

Van Fleet’s three regiments faced two second-rate German infantry divisions—the 416th and the 19th Volksgrenadier Divisions. Worried over their ability to face the Americans in combat, Balck had requested from Commander in Chief West General Feldmarschal Gerd von Rundstedt additional forces to buttress the First Army’s right flank. In response, Rundstedt released two battalions of Generalleutnant Paul Schurmann’s veteran 25th Panzergrenadier Division as a reserve for the First Army’s right flank. In preparation for the American attack, Balck had instructed the two infantry divisions north of Metz to establish a line of battle well back from the river and to engage the Americans in the early hours of the attack from a distance with artillery and mortars.

Shortly after midnight on November 9, soldiers of the 359th, weighted down in full gear, manhandled their assault craft through the marsh along the Moselle’s west bank in preparation for the crossing to Malling. A powerful current swept a few of the boats off their course, but the majority made it across without incident.

Despite rising waters as a result of heavy rains, Van Fleet was able to get eight battalions across the Moselle and by nightfall they had pushed two miles inland in some places. To support the troops in case of a German armored attack, engineers constructed a special raft in which they were able to ferry across several 57mm antitank guns.

The Capture of Königsmacker

Some units were still engaged in trying to capture the Metz forts. On the frigid morning of November 9, 1944, two infantry companies of the 378th Infantry Regiment, 95th Infantry Division, crept silently through the woods at the base of a large hill on the east bank of the Moselle. Their objective was a well-concealed fort known as Königsmacker that stood watch over a key section of the river 20 miles north of Metz.

Königsmacker’s 300-strong garrison from the 19th Volksgrenadier Division was quartered in underground bunkers from which they operated a battery of four 100mm guns encased in steel turrets. The battery’s turrets and various concrete and steel observation posts and blockhouses were the only features visible aboveground. It blocked the route assigned to Van Fleet’s 90th Division, which was to lead the northern pincer of Patton’s double envelopment around Metz, and needed to be neutralized. It was the job of the men of Companies A and B of the 1st Battalion, 378th Infantry Regiment, 95th Infantry Division, to clear the enemy from those structures and also from the underground bunkers.

Just a few hours before, in the predawn darkness, the men had paddled rubber assault boats across the wide river and landed on the east bank unopposed. When the men reached the fort’s barbed-wire perimeter, Bangalore torpedoes were brought forward to breach the obstacle. After a series of staccato explosions, the men rushed the fort.

As the men of the platoon dropped over the parapet on the northwest side of the pentagon-shaped fort, they surprised about half a dozen German soldiers. “One jumped for a machine gun, and the sergeant killed him—fortunately,” recalled Lieutenant Harris Neil, of Company A, 378th Infantry. “The others ran off down a trench and started throwing hand grenades at us. So for a while we had quite a hand-grenade battle—mostly us throwing their hand grenades back at them.”

A three-day struggle for control of the fort was under way.

“Our job was to get the Jerries underground and keep them there,” Neil said. “We wanted to get them underground while we stayed on top and then blast them from one part of the fort to another.”

The Americans braved enemy small-arms fire from within the fort and also mortar and howitzer fire from nearby supporting positions throughout the ordeal. Using new fortress-fighting techniques refined during weeks leading up to the offensive, the men of the 1st Battalion, 378th Infantry, eventually drove the garrison from the fort. They did so in part by collapsing tunnel entrances with satchel charges and by pouring gasoline into ventilation shafts which they then ignited with phosphorus grenades. The road was now open for the 90th Division’s eastward drive.

3,000 Cases of Trench Foot

Eddy’s XII Corps troops fought weather conditions just as determined to defeat them as the Germans. After a partial clearing on the first day of the offensive, the temperature in southern Lorraine dropped precipitously on the second day of the assault. For the next week, precipitation alternated between snow and rain. As a result, U.S. troops, still clad in summer uniforms, found themselves soaked to the bone as they trudged forward along muddy roads past farm fields where manure heaps burned their nostrils with an acrid smell. In some places, troops marching overland found themselves slogging through mud up to their knees. As a result of the conditions, hundreds of cases of trench foot were reported each day. The 26th Division alone reported 3,000 cases of trench foot during the November offensive, Patton said.

On the second day of the attack, tank formations from two armored divisions rumbled over the Seille River. Eddy committed all of Grow’s 6th Armored Division to his left flank, where it could support McBride’s 80th Division and also Irwin’s 5th Division of Walker’s Corps as it closed the southern pincer around Metz. Eddy divided the two combat commands that formed Wood’s 4th Armored Division evenly between the XII Corps center and right. Brig. Gen. Holmes Dager’s CCB of 4th Armored passed through the forward line of Baade’s 35th Infantry Division on November 9, and Colonel Creighton Abrams’s CCA, also of 4th Armored, joined Paul’s 26th Infantry Division the following day.

As the American tanks pushed forward, various Kampfgruppen of Wiethersheim’s 11th Panzer Division moved into position to counter the American thrusts. Wood’s two combat commands advanced east in two columns along parallel roads to speed their advance. Like a ghost in the night, one of Wiethersheim’s Kampfgruppen struck a portion of Dager’s command in the early hours of November 10 at the village of Viviers. For 48 hours, the two sides engaged in a protracted fight in the Viviers-Fonteny area before the German armor broke off the action by executing an orderly withdrawal. By that time, enemy infantry in the XII Corps’ center had quit the Forest of Chateau-Salins and begun falling back toward Morhange.

A Gap in the German First Army

With the German 48th Division in full retreat less than three days into the offensive, Grow’s tank columns pressed ahead as fast as possible in an effort to reach the Nied Française River before the Germans had a chance to reorganize behind it. A sharp engagement unfolded on November 11 at Hans-sur-Nied when a dozen German 88s opened fire on Grow’s CCA as it approached the town’s bridge over the river. Counterfire from U.S. self-propelled artillery silenced the enemy batteries, allowing a portion of the column to establish a shallow bridgehead on the east bank that was expanded the next day. By then, the 48th Division had disintegrated, leaving a dangerous gap in the First Army’s line. To remedy the situation, Balck shifted Generalleutnant Edgar Feuchtinger’s 21st Panzer and General Major August Wellm’s 36th Volksgrenadier Division from other sectors of Army Group G to plug the gap.

Another of Wiethersheim’s Kampfgruppen, comprising 10 Panther tanks and a battalion of panzergrenadiers, trapped a battalion from Paul’s 104th Infantry Regiment in the town of Rodalbe on the Dieuze plateau on November 12. When the GIs took refuge in the cellars of the towns’ homes to await reinforcements, the Panthers fired at the positions at point-blank range with ghastly results. Rodalbe, situated less than two miles south of Morhange, was of great importance to the Germans, and they defended the area tenaciously for nearly a week.

McBride’s infantry had little trouble dislodging the weak German 48th Division from the Delme Ridge in the first two days of the offensive. However, the going was rough for the 317th Infantry Regiment, deployed on the XII Corps’ left flank, which found itself up against the experienced 17th Panzergrenadier Division. Working in concert with McBride’s infantry, Grow’s 6th Armored had as its primary objective capturing the strategic crossroads town of Faulquemont southeast of Metz.

Eddy temporarily halted the advance of his frozen, exhausted infantry divisions on November 12 to protect his left flank and also to adjust for a narrowing of the front resulting from topography. In essence, Baade’s 35th Division in the center was squeezed out of the fighting as a result of the narrowing of the front. When Patton learned that Eddy’s infantry was resting in place, he ordered his subordinate to resume the attack and secure Faulquemont. “It’s easier to defeat the Germans there than on the Saar or on the West Wall,” Patton admonished.

The Battle For Faulquemont

While Wood’s combat commands fought the Germans along the roadways, the infantry had the unpleasant task of clearing them acre by acre from vast tracts of forest. On the Dieuze plateau, Paul’s 328th Infantry Regiment had to pry elements of Philippi’s 361st Volksgrenadier Division from the heavily wooded Koecking Ridge north of the town of Dieuze; the forested tract stretched for five miles across the Dieuze plateau. The heavy rains of the preceding weeks had not spared the forest floor, which like the nearby valleys, was saturated and contained pools of mud that slowed the advance.

Shivering in the dark, dank woods, the GIs were halted frequently by fire from German pillboxes and machine-gun nests. Worse still, they were shelled around the clock by enemy artillery stationed at Dieuze. The fighting in the woods lasted for nearly 10 days, and the deciding factor was the intervention of Abrams’s tanks and armored infantry late in the battle that helped push the enemy from the sprawling forest.

Feuchtinger’s 21st Panzer and Wellm’s 36th Volksgrenadier Divisions reached the battlefield on November 13 and immediately counterattacked American forces on the east side of the Nied-Française. The 21st Panzer went into action first on the 13th against Grow’s CCB at Bazancourt west of Faulquemont, but was repulsed by the Americans.

The main battle for Faulquemont unfolded over November 14-16 between Grow’s CCA and Wellm’s infantry in the countryside south of the town. American field artillery beat back repeated assaults by German infantry, and on the last day of the battle Faulquemont was taken by an American tank attack.

Evacuating the Nazi Party From Metz

Walker had previously determined that he could not depend solely on the crossing points in Van Fleet’s sector, and therefore had ordered Twaddle to send a battalion from the 95th Division across the Moselle in assault boats the same night to secure a bridgehead in the Thionville sector. While the bulk of Twaddle’s infantry kept the Germans inside the Metz forts on the west bank pinned in place, the 1st Battalion, 377th Infantry, later reinforced by the 2nd Battalion, 378th Infantry, landed south of Thionville and in the following days attacked north and capturied Fort Illange.

Morris’s 10th Armored Division was supposed to cross on the second day of Walker’s attack but by that time the Moselle had flooded its banks and inundated the expansive marshland on the west bank. Despite numerous obstacles, Walker’s engineers worked feverishly to complete a pontoon bridge at Malling, despite being under German artillery fire.

On November 11, the day Königsmacker fell to the Americans, the 357th attacked the north end of the ridge containing the Maginot forts. That evening, the engineers completed the Malling bridge in preparation for the crossing of the 90th Division’s support battalions.

Although Balck was willing to leave the 462nd Volksgrenadier Division to its fate inside the Metz fortress, he was not willing to risk having any of the First Army’s other divisions surrounded during the American advance. To prevent this, he planned to establish a new battle line farther east once the situation in Metz became dire.

On the night of November 11, Nazi Party members and First Army administrative personnel stationed in Metz drove east to safety in Citroëns and Renaults commandeered from the city’s residents. South of the city, the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division fell back to a new position behind the Nied-Française.

The German Counterattacks

The first major counterattack by German reserves against Van Fleet’s bridgehead occurred on November 12. In the predawn hours, in which exhausted GIs shivered in their freezing foxholes, 10 German tanks and assault guns of the 25th Panzergrenadier Division attacked Kerling in an effort to recapture the bridge crossing at Malling.

The Germans easily scattered American outposts at Kerling. From that point, one column proceeded on the main road toward Petite-Hettange, while another portion turned south to engage the 2nd Battalion, 359th Infantry, which had been firing on the German flank from protected positions at the edge of the Forest of Petite-Hettange. The battalion’s mortar and machine-gun companies fought valiantly despite being cut off from reinforcements. Company H’s Sergeant Forrest Everhart single-handedly engaged the enemy in a 30-minute grenade duel that kept his company from being overrun. For these actions, Everhart received the Medal of Honor.

Meanwhile, American antitank guns and a scratch force of support personnel guarding the approaches to Petite-Hettange remained in action long enough to check the German advance until the American infantry was reinforced by two American M-18 Hellcats that roared into battle at dawn across the Malling bridge. The arrival of the American armor compelled the Germans to break off the action in midmorning. By then the Germans had lost nine tanks and assault guns and suffered 400 casualties.

On November 13, Germans counterattacked Twaddle’s bridgehead at Uckange, forcing the Americans to seek cover in the houses and stores of two towns, Bertrange and Imeldange, south of Thionville. German half-tracks whirled through the streets of the two towns spraying American positions with machine-gun and small-arms fire until American long-range artillery on the west bank and reinforcements compelled them to break off the attack.

Kittel’s Four Strongholds

The bridges at Malling and Cattenom were constantly under fire from German long-range guns. When the bridges were damaged, tanks and other vehicles were ferried to the east bank on large rafts. To the south, Walker’s engineers worked tirelessly to complete a third bridge in the safety of the 95th Division’s bridgehead at Thionville. The triple Bailey bridge at Thionville was completed on November 14 and, by that time, troops in the two bridgeheads north of Metz had linked up.

Hitler had dispatched Generalleutnant Heinrich Kittel, an expert on fortress warfare, from the Eastern Front to Metz to advise Luebbe how to strengthen its defenses for a final showdown with the Third Army. Kittel arrived on November 8, and when Luebbe suffered a stroke on the 14th, Kittel assumed command, vowing to fulfill Hitler’s orders that the garrison fight to the last man. Once in charge, Kittel decided that he would concentrate manpower and resources to hold four of Metz’s strongest forts––Driant, Jeanne d’Arc, Plappeville, and St. Quentin—all of which were located on the west bank. That evening, the last supply train arrived in Metz from the east. It contained several weeks’ rations and 48 additional artillery pieces.

On November 15, Morris instructed his 10th Armored Division’s CCA to cross at Thionville and CCB to cross at Malling. CCA promptly joined forces with the 357th Infantry and helped it cut two major roads into Metz from the northeast. Meanwhile, CCB linked up with the 359th Infantry and began clearing enemy positions along a network of secondary roads that led east toward Merzig, an important objective in the northwest corner of the Saar.

The Germans launched their last major counterattack against the XX Corps’ bridgeheads the same day Morris’s armor began crossing the Moselle. That morning a strong Kampfgruppe comprising tanks, assault guns, and three battalions of infantry fought its way into Distroff, about five miles east of Thionville, where it grappled with Van Fleet’s 358th Infantry. The fighting raged throughout the morning until American reinforcements arrived and, backed by artillery, compelled the enemy to withdraw at midday.

Also on the 15th, Walker gave Twaddle command of U.S. forces converging on Metz from the north. Twaddle, in turn, appointed Colonel Robert Bacon, commanding officer of the 359th Infantry Regiment, 90th Division, to lead a mechanized task force south along the east bank of the Moselle toward Metz. Two days later, Task Force Bacon had reached the northern outskirts of the city and began battering into submission the enemy garrison at Fort St. Julien using the 150mm self-propelled artillery accompanying the task force.

Preparing to Enter Metz

To the south, Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division had joined the attack on November 9, advancing from its narrow bridgehead at Arnaville, which had been secured during the September fighting. Irwin’s objective was to drive 10 miles to the Nied-Française River and seize the high ground southwest of Metz. In so doing, he would be responsible for severing four major roads into Metz from the south and also the rail line to Saarbrucken.

More than 1,200 B-17s and B-24s pounded the southern ring of forts surrounding Metz and enemy assembly points farther east in preparation for Irwin’s advance. Although the bombs did little damage to the fortifications, they disrupted the communications assets of the 17th Panzergrenadier Division, enabling Irwin’s 2nd Regiment to establish a bridgehead on the east bank of the Nied-Française at Ancerville on November 12.

Alarmed at the speed with which the Americans were advancing directly south of Metz, Balck ordered Feuchtinger’s 21st Panzer to assist the 17th Division in a counterattack. In anticipation of stiffening German resistance, Grow’s CCB had shifted north to assist Irwin, and when the Germans launched a night attack on November 13 at Sanry-sur-Nied, they were repulsed by the Americans, who had vastly greater resources in armor and artillery.

While the 2nd Regiment was engaged with the enemy along the Nied-Française, Irwin’s other two regiments spent several days clearing the enemy from various forts and other fortified positions south of the city. By November 15, Irwin’s units regrouped for a concentrated attack on the city. Because they had more experience with fortress fighting, Walker made a last-minute decision to entrust Irwin’s troops, rather than Twaddle’s, with the capture of the city.

Metz Secured

Irwin’s 10th and 11th Regiments reached the southern outskirts of Metz on the afternoon of November 17. The 11th became hotly engaged with enemy machine-gun units in the hangars at Frescaty airfield while the 10th slipped around to the east and attacked Fort Queuleu, whose garrison put up a determined fight. Meanwhile, Walker told Irwin to instruct the 2nd Regiment to turn north from the Nied-Française and cut the roads through which enemy units were slipping away east to safety.

When the Americans reached the outskirts of the city, Kittel ordered the bridges connecting garrison units on opposite sides of the Moselle blown and issued orders to his soldiers to defend every block and building in the city. Much to his chagrin, the troops within the city itself chose instead to surrender to Patton’s men after a half-hearted fight.

Rather than assault forts on the west bank, as Irwin’s and Van Fleet’s men were doing with the ones on the east bank, Walker ordered the most formidable of them contained until they capitulated. It would be nearly a month before the last holdout of the Metz defenses, Fort Jeanne d’Arc, surrendered to the Americans.

On November 19, the two pincers converging behind Metz as part of Patton’s double envelopment finally met up at Pont Marais about 10 miles west of the city, not far from Boulay-Moselle, the point originally designated for the rendezvous. That same day, Van Fleet’s infantry, marching south, reached the Nied-Française and managed to cut the last roads leading into Metz.

With Metz at last secured, Walker ordered Van Fleet to halt any further advance by his units pending a general regrouping for a push west to the Saar and the West Wall. The 5th Division was able to secure the city with ease, given that the enemy troops inside the city had discarded their weapons and greeted the victors with raised hands.

On November 25, with his troops having rounded up about 4,000 prisoners from the city and the weaker forts, Patton entered the city in a triumphal procession more reminiscent of a conqueror from antiquity than of a 20th-century general. His oratory equaled the pomp with which he had entered the city: “Your deeds in the battle of Metz will fill pages of history for a thousand years,” he told his men. To his credit, “Old Blood and Guts” had good reason to boast, as he was the first commander to capture Metz since Attila the Hun had entered the city in ad 415.

Surrender in the Metz Pocket

By the end of November, only four forts––the very ones that Kittel had chosen to strengthen when he assumed command––were still occupied by German forces. But by December 8, the garrisons at Forts St. Quentin, Plappeville, and Driant had all surrendered, and on December 13 the last stronghold, Fort Jeanne d’Arc, also surrendered to the Americans. From those forts, another 6,000 prisoners were taken, raising to 10,000 the number of troops captured from the forts in the Metz pocket.

Walker had saved many American lives by relying on his corps’ powerful long-range guns to pound the enemy into submission. Patton and his corps and division commanders reaped the rewards of the careful planning they had done the month before—something that had been woefully absent from the Third Army’s effort in September—to get all of the Third Army’s divisions into the fight on the east bank of the Moselle.

An even greater measure of credit goes to men in the ranks who fought past the point of exhaustion in miserable weather against an enemy who excelled at defensive

warfare.

This is Part Two of a Three Part look at Patton’s Lorraine Campaign. Click here for parts One and Three.

I am writing a Graphic Memoir in relation my Grandfather’s WW2 experience. He was in 26th Infantry in France up to Nov 1944 when he was injured and suffered from ”trenchfoot”. This article is very useful information particularly around lack of rain gear at the time. Who is author so I can reference this in my book?

The author’s name, which can be found at the top of the story, is William Welsh.

Why, when fighting in winter weather, would American troops ever not have winter clothing and boots stockpiled for their use?

It’s not as if winter was something sprung on them unexpectedly – you only have to look at the calendar.

Supply/logistics problems, could be caused by any number of reasons. From High Command bumbles, shipping losses, prioritizing glitches, and black-market profiteering. Remember, the Allied Force in the Western European Theatre was MASSIVE, as was the Soviet one in the East. But the Soviets were not as concerned with variety of equipment, as they were of it being simple, effective & cheaply made so the quantity was more of a factor than the quality.

Maybe a little insurance policy would have been to always include winter weather gear and footwear, along with any gun or tank shipment, so as to assure that the GI at least wouldn’t freeze to death, and could remain warm and dry, as he braved the incoming artillery and tanks of the charging Germans.

We wouldn’t let him starve to death, would we? Well, we shouldn’t let him freeze to death, or get trenchfoot, for lack of a good pair of insulated boots, either.