By Patrick J. Chaisson

Red-hot grenade fragments sliced through First Lieutenant Bill Munson’s left arm and shoulder, causing him to fall backwards onto the lip of a German machine gun nest. He saw several enemy soldiers nearby, their distinctively shaped steel helmets silhouetted against the night sky, but was powerless to react. Munson’s Thompson submachine gun, which he held in a death-grip with his one good hand, was completely empty.

His only hope of escape was to play dead. Sprawled halfway across the fighting position, Munson kept absolutely still as bullets fired by friend and foe alike snapped by, inches above his head. Miraculously, he was not injured further in this fusillade.

Sometime later, after things quieted down, Munson heard low voices approaching. To his horror, he realized they were not speaking English. A German kicked him hard in the ribs and wrested the Tommy Gun from his grasp. Then the enemy patrol withdrew under fire from a sudden U.S. mortar barrage, leaving him wounded and weaponless—but alive.

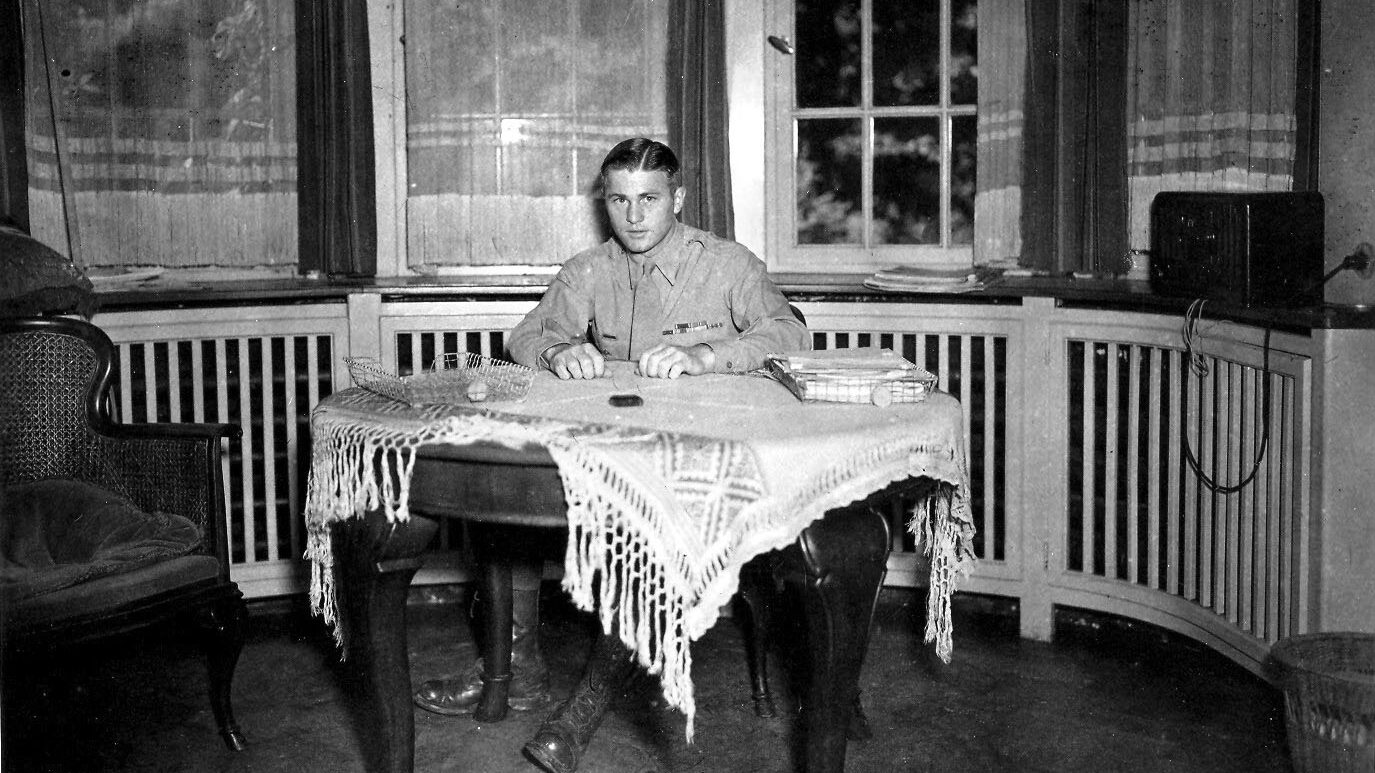

First Lieutenant Orville O. “Bill” Munson, commanding Company A, 48th Engineer Combat Battalion (ECB), endured this harrowing ordeal on the slopes of Mt. Porchia, Italy, during the first week of 1944. Two thousand G.I.s repeatedly assaulted its rocky crest January 4-8, only to be hurled back by ferocious enemy counterthrusts. Artillery, machine guns, and antipersonnel mines took a heavy toll, as did bitter winter weather conditions for which the Americans were wholly unprepared.

In fact, the shortage of fighting men grew so acute that U.S. commanders sent hundreds of highly-specialized combat engineers like Munson into battle fighting as infantry. It was an extreme measure, but one that ultimately succeeded. Allied forces soon put Mt. Porchia to use as a staging area for the next phase of their assault on Rome, 80 miles distant.

For the past six weeks, Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark’s Fifth Army had been engaged in a nightmarish campaign to clear Mignano Gap, a seven-mile pass through the mountains of central Italy. Fifth Army’s objective was to seize a roadway running through the gap known as Route 6. This hard-surfaced thoroughfare, surrounded on all sides by towering, snow-covered peaks, served as a main supply route leading north from Allied beachheads at Salerno.

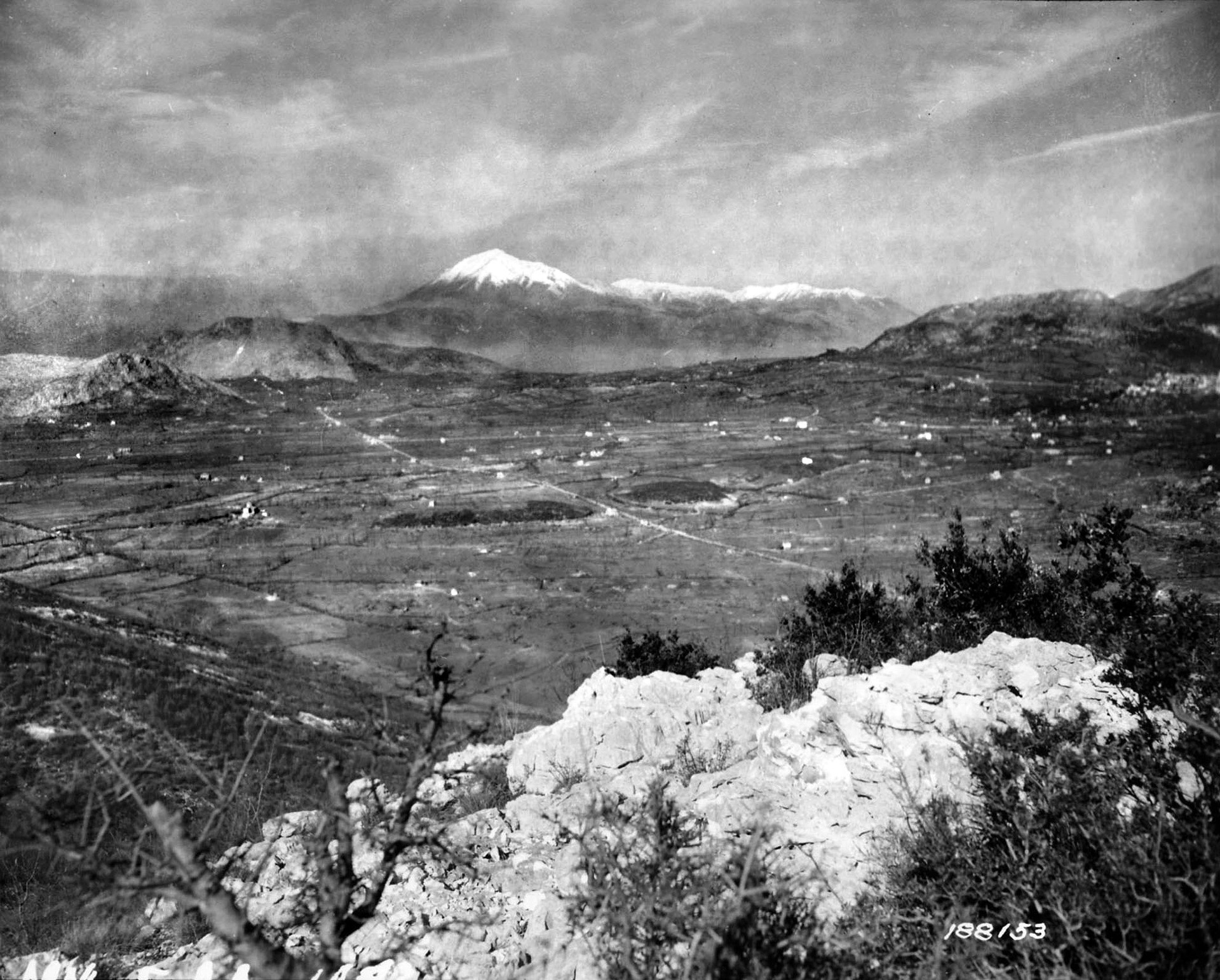

By New Year’s Day 1944, American troops had battered their way through the Mignano Gap to reach Mt. Lungo at its northwestern terminus. Ahead lay a river valley, five miles long and relatively level except for a long, craggy height that rose like a fist 180 feet above the floodplain. This hilltop, which dominated the surrounding terrain in all directions, was labeled Mt. Porchia on U.S. maps.

Mount Porchia and its approaches sat within the II Corps area of responsibility. Commanded by Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes, II Corps had recently been reinforced by the powerful 1st Armored Division (1AD), nicknamed “Old Ironsides.” Yet Keyes recognized that mountain warfare required foot soldiers, not tanks, and 1AD’s order of battle included just one regiment of riflemen—2,400 troops in all. That outfit, the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment (AIR), was heavily engaged during the North Africa campaign but did not participate in the landings at Sicily or Salerno. Although it hadn’t seen combat in eight months, the 6t h AIR was fresh, ready, and battle-tested.

For reasons that remain unclear, Keyes organized his Mt. Porchia assault force in a somewhat unorthodox fashion. Instead of assigning the mission of capturing it directly to the 1st Armored Division, Keyes detached certain units from “Old Ironsides” to form a temporary battle group under II Corps’ direct supervision. Designated “Task Force Allen,” this formation was commanded by Brig. Gen. Frank A. Allen, normally the head of 1AD’s Combat Command B.

General Allen’s outfit consisted of the 6th AIR, 1AD’s entire Division Artillery (54 guns), the 701st Tank Destroyer (TD) Battalion, and two non-divisional armor outfits, the 753rd and 760th Tank Battalions (TBs). All except the 760th TB were previously tested in action. In addition, the 1108th Engineer Combat Group (a II Corps asset) stood ready to support the attack, as did smaller signal, medical, and service support elements drawn from 1AD and II Corps.

When the “Old Ironsides” commander Maj. Gen. Ernest N. Harmon learned II Corps was taking nearly half his division away for the Mt. Porchia operation, he objected loudly. Harmon felt the assignment could be better handled by his unit, which had trained and fought as a team for years, rather than by an impromptu task force under someone else’s control. His anger cooled only slightly when he was told 1AD’s tanks were being held ready for an armored breakthrough that Fifth Army was planning to execute in the near future.

Facing TF Allen on Mt. Porchia were grenadiers of the 44th Infantry Division, also known as Hoch- und Deutschmeister (Grand Master of the Teutonic Order). Annihilated at Stalingrad, the 44th was brought back up to strength by an influx of mainly Austrian recruits and moved to Italy during the autumn of 1943. Assigned to the German 10th Army, these soldiers then participated in a masterfully-executed delaying action along the Wehrmacht’s Bernhardt Line.

This belt of pillboxes, covered gun emplacements, and heavily-guarded obstacles was meant to slow the Allies’ advance in order to buy time for workers to finish constructing the Gustav Line, a more extensive system of defensive fortifications covering the Garigliano and Rapido rivers. Heavy losses were to be avoided, said 10th Army commander General Heinrich von Vietinghoff. “In the event of attacks by far superior enemy forces,” he directed, “a step-by-step withdrawal to the Gustav position will be carried out.”

The 44th Infantry Division’s riflemen had been doing just that for months, utilizing massed field artillery and mortar fire directed by well-positioned forward observers to decimate Allied attackers. When time came to give ground, the Hoch- und Deutschmeister left behind thousands of landmines–including the antipersonnel S-mine (a fearsome projectile that G.I.s called the “Bouncing Betty”) and a nearly undetectable explosive device called the Schü mine (capable of shattering foot, ankle, and shin bones).

On January 1, 1944, the 44th Infantry Division defended two isolated but commanding peaks three miles northwest of Mignano Gap. Along the division’s left flank stood troops of the 132nd Infantry Regiment, holding key terrain at Mt. Majo. On the right, occupying Mt. Porchia, was an understrength battalion of the 134th Infantry Regiment. The Germans were well-supported by heavy mortar, field artillery, and Nebelwerfer rocket launchers, while a contingent of elite Luftwaffe paratroopers from the Hermann Goering Division could be rushed up in an emergency from reserve positions some distance behind the line.

In addition to their lavish use of landmines, the 44th’s grenadiers outposted several stone farmhouses well forward of the Mt. Porchia strongpoint. All road junctions and other identifiable landmarks were registered with artillery, while a sophisticated system of fire control was established using wire communications and signal flares. The Hoch- und Deutschmeister, dug-in and ready, would not surrender this highly defensible ground without a fight.

Cold winds and rain that occasionally turned to sleet or snow prevailed during the first week of January, 1944. While these raw, wintry conditions affected both adversaries, few records have survived that describe their impact on German forces. We do know that U.S. medical officers reported 513 cold-weather injuries during the Mt. Porchia operation, mostly due to exposure and trench foot. Poor hygiene and inadequate footwear contributed greatly to this situation, which may have incapacitated an alarming 11 percent of all personnel belonging to TF Allen.

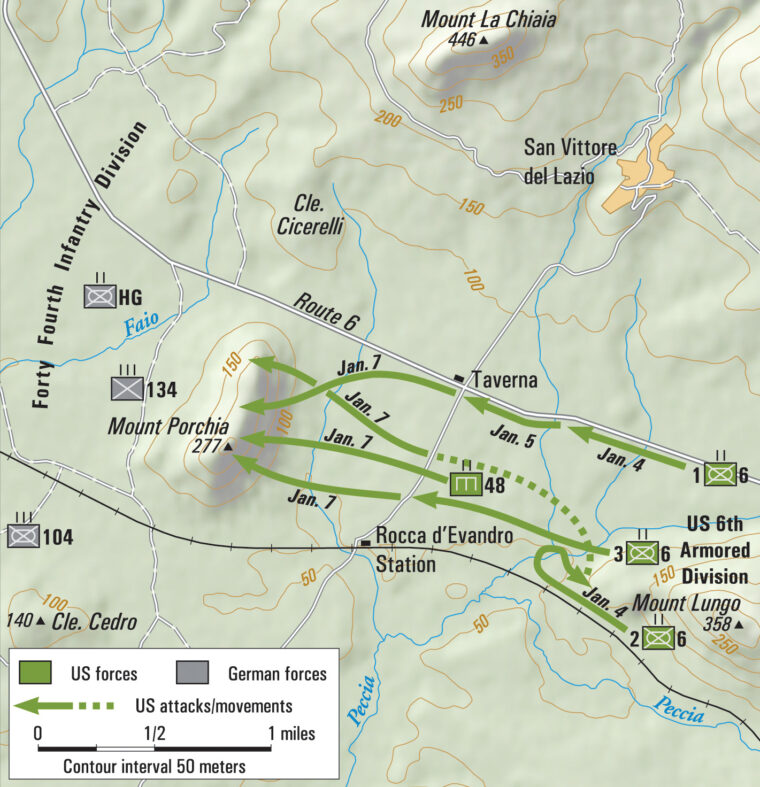

Deep mud, a byproduct of the miserable weather, largely confined vehicle movement to Route 6, which ran east-west along the northern edge of the battlefield. Just east of Mt. Porchia itself was an unimproved dirt road christened “Knox Avenue” by the Americans. This track would serve as a line of departure, or starting point, for their final rush up the mountain. Another thoroughfare, an abandoned railroad bed called Route 48 after the engineer battalion that was transforming it into a roadway, ran roughly parallel to Route 6 but about 1,100 yards south.

Task Force Allen’s soldiers occupied positions along the nose of Mt. Lungo, approximately 2,500–3,000 yards from their objective on Mt. Porchia’s summit. The terrain between Lungo and Porchia was mostly flat, except for a few low hills flanking Route 6. These hummocks, along with a few derelict farm buildings scattered about the plain, remained under German control.

This meant that, before they could storm the mountaintop, Brig. Gen. Allen’s G.I.s needed to clear a zone of approach nearly two miles long from their determined and battle-wise foe—all while under direct observation from artillery spotters calling down fire from the crest of Mt. Porchia. It was not a scenario designed to inspire confidence in those who would make this hazardous frontal assault.

The U.S. attack plan relied on simplicity, as it had to be carried out after sunset on Tuesday, January 4, 1944. Two battalions, 1st and 2nd, would form to the west of Mt. Lungo with 3rd Battalion kept in reserve. On a prearranged signal, the infantrymen were then to advance toward Knox Avenue, reorganize briefly, and rush their objective. The idea was to take Mt. Porchia before sunrise.

To handle enemy strongpoints along the way, 1st Battalion would have the 753rd TB in support while the 760th TB was to follow 2nd Battalion. Tasked with the mission of suppressing enemy positions on Mt. Porchia were well over 100 mortars and howitzers, even some British-crewed long-range artillery pieces firing from the adjacent 10th U.K. Corps zone. Poor visibility caused by low-hanging clouds, however, prevented Allied airpower from lending its weight to the assault.

Late on January 4th, hundreds of foot soldiers began filing off Mt. Lungo while a 30-minute cannonade shook Mt. Porchia 3,000 yards to their front. At 1930 hours, the infantry attack kicked off. First Battalion’s advance to the north was quickly stalled by fierce resistance coming from the two knobs guarding Route 6. On the left, 2nd Battalion halted to wait for that fight to cease.

German observers saw these riflemen standing exposed on open ground and called in a volley of heavy mortar fire. This barrage caused so many casualties that Brig. Gen. Allen paused the attack—his medics required time to carry off the wounded. Second Battalion now lacked sufficient manpower to continue its mission; the task force reserve, 3rd Battalion, moved forward to replace it.

It was a costly and disappointing start to the operation. The Americans advanced perhaps 200-300 yards that night, suffering an estimated 35-45 percent of their assault force killed, missing, or injured. Dawn brought with it both a snowstorm and a battalion-sized enemy counterattack that was only broken up by point-blank tank and TD fire.

At 1515 hours on January 5, 3rd Battalion resumed the advance. Guiding on the abandoned railway bed called Route 48, this unit succeeded in reaching Knox Avenue. That night, 3rd Battalion’s troops dug in along the line of departure while those of 1st and 2nd Battalions moved up to establish assault positions on their right flank.

Officers and NCOs struggled to get their men ready for the final attack on Mt. Porchia’s slender crest, now set to begin at 0700 hours on January 6. Heavy losses reduced some rifle companies to a few dozen effectives, a situation made worse by large numbers of stragglers separated from their commands. Those infantrymen along Knox Avenue needed to be resupplied with ammunition, rations and water, a process that took most of the night. Few of them got any sleep.

A preparatory artillery bombardment commenced around daybreak, mixing high explosives with chemical smoke to conceal advancing U.S. soldiers from enemy observation. At 0700 hours, the attack lurched forward. An American correspondent, Don Whitehead, vividly portrayed the action in 1st Battalion’s zone that morning:

“Captain Ralph C. Fisher of Hyattsville, Md., stood up before his detachment and shouted ‘I’m going up that mountain!’

“Fisher started straight up the slope of the northeast corner with his men right behind him. They battled their way through enemy machine gun nests straight to the objective…Only half the men who went up the mountain with Fisher reached their goal because of the heavy enemy fire. But those who did dug into positions and quickly prepared to stave off counter-attacks.”

Fisher, who commanded Company B of the 6th AIR, earned a Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism on Mt. Porchia but never lived to receive it. Struck by shellfire a few days later, he died of his wounds in an American field hospital on January 13.

Another group of brave G.I.s supporting the attack that day belonged to the 47th Armored Medical Battalion. One of those aidmen, Pfc. Henry J. Guarnere of Philadelphia, lost his life to enemy mortar fire while carrying casualties off the hillside. William, his younger brother and a paratrooper serving with the 101st Airborne Division, learned of Henry’s death the night before he jumped into Normandy—a scene poignantly described in the book and mini-series “Band of Brothers.”

On this deadly battleground, German shellfire punished fighting men and noncombatants with equal vehemence. First Lt. Arthur C. Lenaghan, the outfit’s Catholic chaplain, was struck by artillery fragments on January 6 while volunteering as a litter bearer. Evacuated to an aid station, he died the next day.

By early afternoon, Allen began receiving reports indicating that 6th AIR was now on top of Mt. Porchia. At dusk, however, three companies of paratroopers from the Hermann Goering Division counterattacked and pushed those troops back off the mountain. Worse still, a gap in the lines had developed south of 3rd Battalion—and there were no reserves available to plug it.

Desperate times called for desperate measures. The 48th ECB, until recently in charge of rehabilitating Route 48, received a warning order from Headquarters, TF Allen, at 1315 hours on January 6, directing them to cease all construction activity and prepare to fight as infantry. The formal directive attaching one company of engineers to each of 6th AIR’s three rifle battalions came down at 1750 hours.

This did not sit well with Lieutenant Colonel Andrew J. Goodpaster, the 48th’s commanding officer. Goodpaster preferred that his three line companies fight under battalion control rather than being parceled out piecemeal as TF Allen instructed. Yet the order made sense, as combat engineers lacked the mortars and radios found in a rifle company. The men of the 48th ECB would have to rely on their infantry comrades for communications and fire support—along with normal resupply and casualty evacuation—as long as they remained attached to the 6th AIR.

First Lietenant Orville “Bill” Munson of Company A, 48th ECB, had been watching Mt. Porchia “being lit up like a blinking Christmas tree” by Allied artillery ever since the operation kicked off on January 4. That was also the day he took over as company commander after watching the outfit’s previous CO being loaded into an ambulance due to combat exhaustion. Fortunately, Munson, a 24-year-old South Dakota native, was by then a seasoned officer who knew and trusted the engineers under his charge. This was their first time fighting as infantry, though, a fact undoubtedly on many of the troops’ minds as they jumped off shortly after nightfall on January 6.

With First Sergeant Donald F. Buckley at the rear of the march column keeping an eye out for potential stragglers, Munson’s force made its way toward Knox Avenue. Danger lurked everywhere; frequent German illumination flares required everyone to halt in place while occasional mortar barrages further slowed progress. One unlucky sergeant stepped on an S-mine and went down with a mangled leg; the blast also wounded Buckley and several other soldiers. Bleeding heavily himself, the first sergeant immediately organized a detail of engineers to haul their most critically injured casualties back to an aid station.

While attempting to locate the infantry’s command post, Munson encountered a single German grenadier coming down the mountainside and killed him with a burst from his Thompson gun. Finally, messengers informed him the attack would renew at 2200 hours. Company A’s combat engineers were to dash straight up the hill “screaming to high heaven” as they ran. Riflemen from 1st Battalion, he was told, would advance on their right flank.

The attack came as a complete surprise to Mt. Porchia’s defenders. Company A encountered only scattered small-arms fire during its assault but did suffer some casualties due to mines and booby traps. Munson was surprised to learn, however, that only about 50 of the 95 engineers under his command followed him up to the summit. Without 1st Sergeant Buckley to watch them, several soldiers simply disappeared into the darkness, only to reemerge after all shooting stopped.

Fortuitously, Company A possessed a secret weapon on Mt. Porchia. His name was Pfc. Richard F. Stern, a 45-year-old immigrant who won the Iron Cross for frontline service with the German Army during World War I. A Jew from Nuremberg, Stern escaped Hitler’s regime in 1939 and joined the U.S. Army shortly thereafter “to get back at the Nazis” as he told one reporter.

Now facing enemy machine-gun teams on Mt. Porchia’s shoulder, Pfc. Stern stood up and began calling out to the foe in his native language. Saying the Americans had them surrounded, he convinced six grenadiers to come forward with their hands up. Stern later received a Silver Star and promotion to sergeant for his persuasive “war of words” that night.

In reality, Stern and his fellow G.I.s were the ones in danger of being cut off. Critically short of troops and ammunition, Munson made the difficult decision to withdraw from Mt. Porchia’s crest at 0400 hours on January 7th. While leading Company A off the mountain he was hit by grenade fragments and left for dead. Luckily, the young engineer officer managed to reunite with his command later that morning. Bill recalled, “When the men saw me they all hollered at once.” Private Stern, he said, “…was so emotional he threw his arms around me and cried.”

Before being sent back for medical treatment, Munson briefed Lt. Col. Goodpaster on his confusing and poorly coordinated night attack. He also told Goodpaster that the Germans kept only a small garrison on Porchia’s heights during daylight hours, moving reinforcements up after sunset to sweep the summit clear of any small American units that managed to get that far.

This bit of battlefield intelligence prompted Goodpaster, a 28-year-old career officer from Illinois, to contact TF Allen’s headquarters with an idea. Return his line companies to battalion control, he suggested, and the 48th ECB would lead a daylight “march and fire” assault up Mt. Porchia. The plan was quickly approved; at 1600 hours, 340 combat engineers stormed up the hillside. In support were machine gunners from the 6th AIR and some straight-shooting U.S. tankers.

Lead scouts from Company B spotted a German anti-tank gun that was holding up the advance. Guided by their tracer bullets, an M4 Sherman firing from the valley floor made short work of that troublesome cannon. Meanwhile, Lt. Harry Thames of Company C shot and killed an enemy sniper at 300 yards. This feat of marksmanship, together with his other exploits on Mt. Porchia, resulted in award of the Distinguished Service Cross.

That afternoon, Company C’s Sergeant Joseph C. Specker of Missouri singlehandedly destroyed an enemy machine-gun position despite being gravely wounded and unable to walk. Unit members later found the sergeant dead at his post. Specker’s valor was recognized with a posthumous Medal of Honor—the first such decoration awarded to a combat engineer during World War II.

Reaching the top, Company B’s Tech. 5 Ben Santjer encountered a squad of enemy soldiers at extremely close range. He shot four grenadiers and bayoneted a fifth before succumbing to a hail of machine pistol bullets. Santjer’s sacrifice enabled the rest of his unit to outflank the German defenders and kick them off Mt. Porchia for good. He earned a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross.

It should be mentioned that the 6th AIR’s senior leaders were not sitting idly by while Lt. Col. Goodpaster led the 48th ECB up Mt. Porchia on the afternoon of January 7. Notably, 1st Battalion’s Lt. Col. Lyle J. Deffenbaugh and 2nd Battalion’s Lt. Col. Elton W. Ringsak distinguished themselves by organizing provisional rifle companies made up of cooks, clerks, and mechanics, then personally guiding those troops up the mountainside. Other officers and senior NCOs roamed the battlefield in search of lightly wounded casualties or soldiers separated from their outfits. Task Force Allen was already starting to reconstitute itself for follow-on missions.

By dusk, U.S. forces firmly controlled their objective. A weak counterattack that came in at 0100 hours was easily beaten back; throughout the night, occasional long-distance shellfire dropped onto the mountaintop but caused relatively few losses among the dug-in riflemen and combat engineers occupying it. Grenadiers and paratroopers, cut off from their parent organizations, began to surrender—the 48th ECB, for example, took 33 prisoners on Mt. Porchia.

Lieutenant Colonel Goodpaster was out inspecting his company positions at 1000 hours on January 8, when he was struck in the right arm by shell fragments. Also injured in that barrage was Lt. Col. Ringsak; shrapnel from an exploding mortar round severely damaged the left temporal region of his brain and left him partially paralyzed. Goodpaster eventually returned to duty (retiring in 1981 as a four-star general) but not Ringsak—he did, however, make a full recovery and go on to serve as a North Dakota State Senator for 17 years.

Bill Munson stayed two nights at the 94th Evacuation Hospital before rejoining Company A on January 9. He received a Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism on Mt. Porchia, ending the war as a major in charge of the 48th ECB’s operations section. Munson’s Purple Heart earned during the attack was the first of four such awards this superb combat leader would receive for wounds sustained during an eventful 22-year military career.

More accolades followed. Both the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment and the 48th Engineer Combat Battalion were awarded a Presidential Unit Citation in recognition of their soldiers’ extraordinary gallantry during the Mt. Porchia operation. Afterward, letters of commendation also went out to the various tank, TD, artillery, and service support organizations that helped ensure the success of Allen’s attack.

The 48th Engineers remained on Mt. Porchia for two full days before they came down to resume their normal duties of road maintenance and mine clearing. It wasn’t until January 12, however, that the 6th Armored Infantry’s half-frozen and exhausted survivors were relieved by elements of the 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th “Texas” Infantry Division. The 6th AIR would require a significant infusion of replacements and weeks of training before it could again be considered combat-ready.

In 10 days of fighting, TF Allen sustained 66 men killed, 379 wounded, and an unknown number missing in action. The 6th Infantry alone reported upwards of 480 soldiers still unaccounted for at battle’s end, although most were found and returned to duty within a few days. Straggling, as Lt. Munson noted, was also a problem in support units such as the 48th ECB.

Nearly a battalion’s worth of G.I.s in TF Allen required treatment for non-battle injuries, keeping these troops out of action when they were most needed on the front line. Frozen feet, in particular, plagued the U.S. Army in Italy throughout that brutal winter of 1943-44. Frigid wind and rain, coupled with the logistics system’s inability to supply even basic personal items like clean socks, undoubtedly contributed to this high rate of cold-weather casualties.

Yet there was good news coming from newly captured Mt. Porchia during the second week of January, 1944. Reconnaissance patrols sent out to examine Mt. Trocchio, another isolated peak located three miles forward of U.S. lines, found that height completely unoccupied. The Germans appeared to have withdrawn to the Gustav Line, completely abandoning Trocchio and its commanding view of the Italian countryside.

American senior officers quickly made their way to an overlook on Mt. Trocchio’s broad crown. What they saw through their binoculars filled these men with renewed hope.

Only a few miles distant, the wide Liri Valley beckoned. This high-speed avenue of approach led directly to Rome, a drive of perhaps 75 miles through terrain ideally suited for the “Old Ironsides” Division’s 250 Sherman tanks. Here at last was an opportunity for Fifth Army to finally break out of its agonizing mountain-by-mountain slog up Italy’s spine. Plus, it was common knowledge that Mark Clark very much wanted to capture Rome.

There were a few additional terrain features visible to the U.S. commanders gathered on Mt. Trocchio. Along Route 6 at the mouth of the Liri stood a nondescript village known as Cassino, which Clark would have to occupy before his tanks could begin their advance on Rome. Steeply-sloped highlands set back a half-mile beyond Cassino provided excellent observation posts for enemy artillery spotters. Atop one of those ridges, an ancient Benedictine abbey towered over the surrounding landscape.

One mile west of the Americans’ outpost, a swift-flowing river labeled the Rapido on Allied maps (it was really the Gari River) presented a more immediate obstacle. This water feature required combat engineers to bridge it so II Corps could seize Cassino and those mountains guarding the Liri Valley. First, though, U.S. infantry needed to cross the Rapido (Gari) in small assault boats to take and hold the far shore.

To the officers looking down from Mt. Trocchio, it seemed like a relatively straightforward operation. To get this far, Clark’s men had already crossed plenty of rivers and scaled many a mountain. The Rapido/Cassino region, some confidently predicted, would fall to Allied troops within a week at most.

Crushing these dreams of easy conquest were 90,000 soldiers of Germany’s XIV Panzer Corps, who on January 20 hurled back Fifth Army’s first assault crossing at the Rapido. These troops, some of whom were veterans of the struggle at Mt. Porchia, waged a tenacious and well-executed defensive action on the Gustav Line at Cassino throughout the spring of 1944, keeping the Liri Valley blocked until mid-May.

By then, Clark had given up all hope of a simple, bloodless, and triumphant advance on Rome. He would not get there until June 4, and only after enduring a series of costly battles in places with names like Cassino, Anzio, and the Rapido River. Thousands more fighting men were destined to die, go missing, or suffer ghastly wounds before Allied forces finally entered the Eternal City.

Patrick J. Chaisson writes from his home in Scotia, New York. The author wishes to thank Mr. Troy Morgan of the U.S. Army Engineer Museum, Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, for his invaluable assistance in the preparation of this article.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments