By A.B. Feuer

In the Spring of 1944, Japanese Admiral Soemu Toyoda assembled a large fleet of warships at Tawi-Tawi in the southern Philippine Islands. There was no doubt in his mind that Allied military forces would continue their westward drive across the Pacific, but he was uncertain as to the direction of the next attack.

General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific, had firmly established beachheads in New Guinea, and Japanese scout planes had reported that an American task force was gathering in the neighborhood of the Marshall Islands. Toyoda realized that the U.S. naval force assembling in the Marshalls could strike at Guam or Saipan in the Marianas—or MacArthur, using New Guinea as a base of operations, could attack the Palau Islands.

American Assault on the Palau Islands

By this stage of the war, the Japanese Navy would have had a difficult task defending both sectors at the same time. Therefore, Toyoda decided to choose Tawi-Tawi—because of its central location—for his fleet buildup. From there, the Japanese admiral would be able to send his forces in either direction.

In May 1944, the Japanese High Command received Intelligence that Manus Island, in the Admiralty group, was being geared up as a springboard for an American assault on the Palau Islands. MacArthur’s troops were also reported gathering at points along the New Guinea coast. Even so, Toyoda felt that an attack on the Marianas remained a distinct possibility. He needed to learn, with exact certainty, in which direction to send his fleet, and an operational plan was quickly implemented.

Toyoda established a submarine scouting line extending from Truk Island in the Carolies to a point just west of Manus. His submarines were stationed at designated intervals along the line and positioned so that any invasion fleet could, hopefully, be detected. The vessels assigned to that operation were I-16, RO-104, RO-105, RO-106, RO-108, RO-116, and the RO-117.

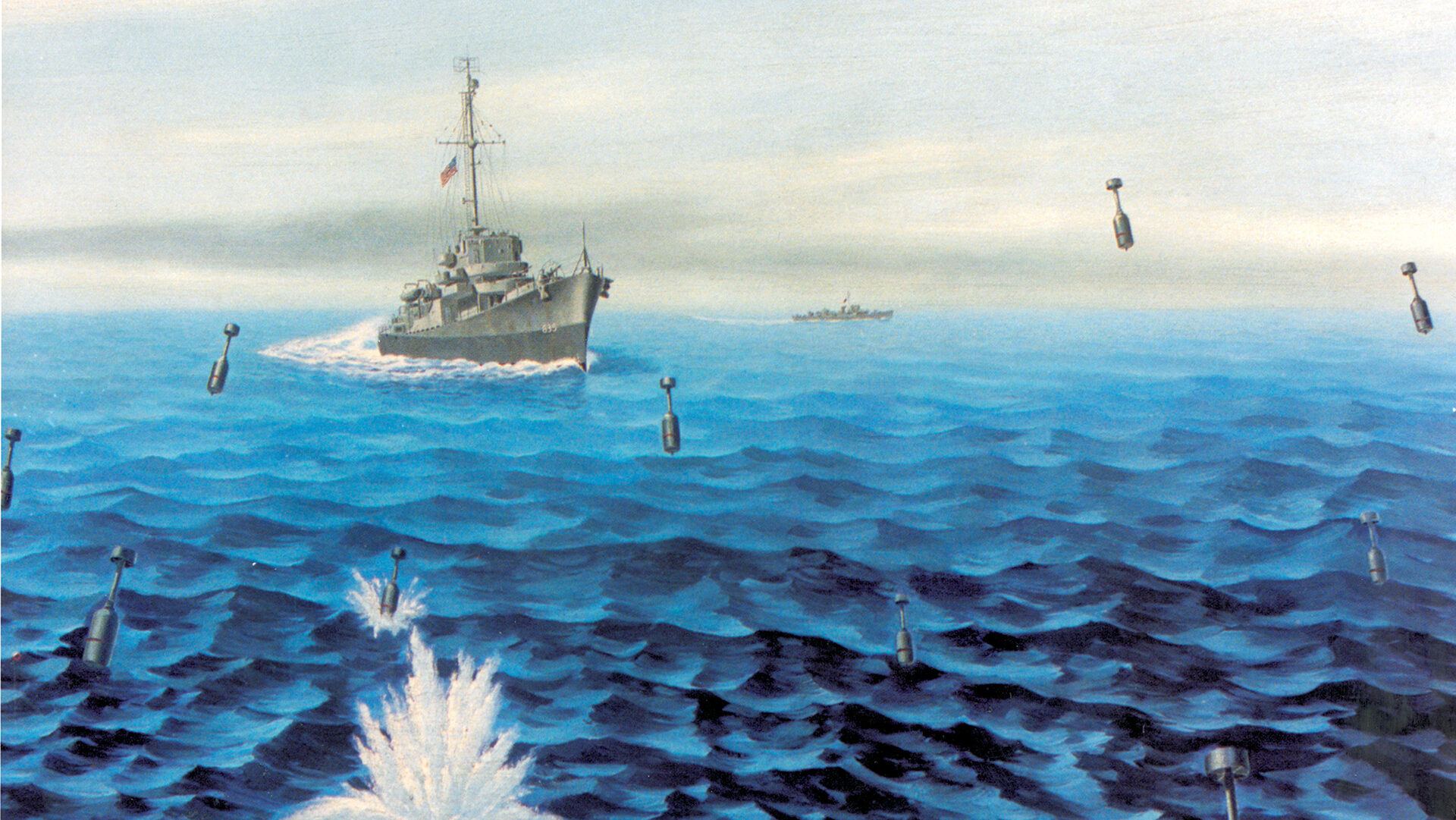

The Hedgehog: Forward-Throwing Anti-Submarine Mortars

Toyoda reasoned that he had all bases covered. The odds appeared even except for two factors—the arrival of a squadron of new U.S. Navy destroyer escorts (DEs) and the infamous Hedgehog weapons with which they were armed.

During the spring of 1940, Commander Charles Goodeve of the British Royal Navy and its Department of Miscellaneous Weapons Development, came up with the innovative idea of a forward-throwing mortar for antisubmarine warfare. Satisfactory trials of the device were carried out in May 1941, and the weapon was then put to good use by the Royal Navy against the German U-boat menace.

The new but simple device consisted of a steel box holding four rows of six grenade-type missiles. The weapon was fired like a rocket launcher. And, when loaded with 24 projectiles, it gave the appearance of the bristling back of a porcupine—hence the name Hedgehog.

Instead of dropping antisubmarine charges off the stern of a ship, the Hedgehog fired its grenades forward—about 250 yards ahead of the vessel. The Hedgehogs did not explode like conventional underwater weapons, which had to be set at a specific depth. In order to detonate, the projectile had to make actual contact with a solid object. After being catapulted toward a target, however, a 24-shell salvo provided an excellent chance for a successful attack. Regular depth charges still had a function. They were often used in conjunction with Hedgehogs, especially if the enemy submarine had gone deep.

The Hedgehog proved to be so successful in the Atlantic that U.S. Navy Captain Paul Hammond, working with British engineers, developed the weapon for use aboard American warships. In early May 1944, while Toyoda was busy setting up his defensive strategy, a new destroyer escort (DE), the England, arrived at an American base in the Solomon Islands.

On May 18, the England, captained by Lt. Cmdr. Walton B. Pendleton, was assigned to Escort Division 39. The division also included the DEs George and Raby. All three ships had been fitted with Hedgehogs.

Sinking I-16

On the previous day, the Japanese submarine I-16 was reported to be heading south from Truk with supplies for the isolated garrison at Buin on the southern tip of Bougainville. Escort Division 39 received orders to patrol an area northwest of Buin to try to intercept the enemy vessel. Upon reaching their designated position, the DEs steamed in a parallel line about 4,000 yards apart. Calculating the submarine’s speed and course, Division 39 expected to make sonar contact with I-16 on or about May 20.

At 1 pm on May 19, England suddenly made a sound contact at a depth of 100 feet. The submarine quickly became aware of its enemy and headed deep. The Japanese captain began to fishtail his sub to avoid a depth-charge attack. The England made a wide swing and raced toward her target. I-16 continued evasive maneuvers and managed to escape four Hedgehog runs. Whenever England approached to within 600 yards of I-16, the submarine’s captain would turn sharply into the DEs wake, obscuring his sub’s movements.

On her fifth run at the enemy, however, England’s sonar locked on the submarine. At 2:33, the order was given to “fire Hedgehogs!” Twelve seconds after splashing the water, four of the deadly missiles exploded. Two minutes later, a violent underwater explosion erupted astern of England, lifting her clear off the water. Her crew was tumbled about, and some thought that their ship had been torpedoed.

Momentarily, large quantities of oil and debris began to bubble up to the surface. England lowered a whaleboat near the center of the expanding oil slick. Rubber bags containing rice were recovered, along with broken pieces of furniture and cork insulation.

Moving On to the RO-106

Two theories were advanced to explain the heavy underwater explosion. The Japanese submarine might have been severely damaged, and the captain could have set off a detonation device that destroyed his ship. Or the crippled sub may have sunk so rapidly after being hit that water pressure crushed its hull, setting off its torpedo warheads.

In the meantime, while England was busy stalking I-16, a U.S. Navy patrol bomber spotted RO-117 and sent it to a watery grave. Admiral William F. Halsey, commander of the U.S. Third Fleet, was notified of the two submarine kills and assumed that there were probably other “prying eyes” in the neighborhood. He immediately dispatched Escort Division 39 to the location where RO-117 was destroyed.

Early on the morning of May 22, the three DEs were patrolling Admiral Toyoda’s scouting line west of Manus Island. At 3:50 am George reported a surface contact at seven miles; England also picked up the target and dashed ahead at full speed. Pendleton hoped to get in position to flank the stranger and box it in.

Minutes later, George turned on her searchlight and swept the area. A submerging submarine was suddenly illuminated. George fired a Hedgehog salvo at the rapidly diving boat, but no hits were registered. England’s sonar soon located the escaping enemy sub, and she launched her Hedgehogs without success. Pendleton circled around for another attack, and at 4:45 another full load of grenades was fired from the destroyer escort. Bull’s-eye! Three explosions were heard at a depth of 240 feet. As England came about for another pass over its target, a heavy underwater eruption rocked the ship. Pendleton headed for the center of the explosion site. An oil slick was forming on the water, and a small quantity of debris was recovered. Pendleton, in a letter to COMSUBPAC (Commander Submarines Pacific) theorized that the enemy submarine was badly damaged by the Hedgehogs, and its captain, rather than risk capture, exploded his warhead magazine. The confirmation of that theory was lost with the captain and crew of RO-106.

Escort Division 39 continued its search-and-destroy mission along Toyoda’s scouting line. The early morning of May 23 was dark and overcast, and the DEs had to depend on their surface-search radar to spot the enemy. A depth of 3,300 feet registered on the fathometer.

At 6:10 am, Raby reported that she had picked up a surface contact at a distance of four miles. England immediately changed course to close on the target and raced ahead at full speed. Moments later, Raby radioed that the contact was submerging. England and George quickly reached the target area and plotted information received from Raby.

Wrecking the RO-108 and Entering Seeadler Harbor

At 7 o’clock, the George picked up the submarine (RO-104) on sonar and dashed to the attack. Five Hedgehog salvos were fired, but no hits were registered. England was ordered to try her luck. At 8:19, the sub-slayer sped in for her third kill. Pendleton’s first Hedgehog salvo missed, but the second hit the jackpot. Approximately 10 projectiles struck the enemy sub and exploded. A few minutes later, a heavy explosion was heard and large quantities of oil and debris began floating to the surface. As in the other cases, it was believed that the submarine had been crippled, and the crew committed hara-kiri by deliberately detonating its warheads.

Shortly after midnight on May 24, George reported she had picked up a submerging submarine at a distance of seven miles. England raced to intercept the enemy and soon made sonar contact at a depth of 165 feet. Pendleton fired a full barrage of Hedgehogs. Three projectiles exploded on the target. All hands waited expectantly for the usual large explosion, but the sea was silent—nothing on sonar.

The three DEs circled and searched the area. The surface of the water for many miles from the attack point was coated with a thin film of oil, pieces of deck planking, and cork. Evidently the submarine, RO-116, had been badly damaged but continued moving for several minutes before sinking.

By that time, the ships of Division 39 were running low on oil and Hedgehogs. At 11 pm on May 26, while steaming for Manus Island to refuel and load ammunition, England and Raby made a surface contact at a range of five miles. The target, RO-108, immediately submerged but was rapidly picked up by England’s sonar. Minutes later, England launched a Hedgehog salvo. Several tremendous explosions quickly turned the quiet waters to a bubbly froth. Pendleton’s ship circled the area until dawn. At the center of the blast, oil was still seen rising to the surface. A whaleboat was lowered, and a large amount of wreckage was recovered.

On the afternoon of May 27, England, George, and Raby steamed into Seeadler Harbor at Manus. The destroyer escort Spangler was waiting for them with a fresh supply of Hedgehogs. The following morning, after refueling, the rugged submarine chasers headed back out to sea. They were joined by Spangler and the destroyer Hazelwood.

At 2 am on May 30, Hazelwood made a sonar contact at about eight miles. The destroyer attacked with conventional depth charges, but was unable to flush the submarine. The four DEs were directed to help search for the enemy craft.

Six Submarines in 12 Days

Throughout the day, RO-105’s captain played cat-and-mouse with his antagonists. The frustrated American ships were unable to maintain regular contact with the elusive submarine.

Finally, at 3:20 am on May 31, George and Raby regained sound contact with the enemy sub. England and Spangler soon arrived on the scene. George and Raby had been firing Hedgehog barrages, without success. Spangler was then called in to try her luck. Again, nothing.

Around daybreak, Admiral Halsey advised Escort Division 39 that Japanese aircraft were in the vicinity and for the division to leave the area fast. Frustration aboard England was very evident. She still had not fired one salvo at the cunning submarine. Pendleton requested permission for one last shot and was given the green light.

At 7:30, England made a good sonar contact at 1,650 yards and headed into her firing run. RO-105 tried to swing away from the attack, but Pendleton was not fooled. He launched a Hedgehog salvo in the direction the submarine was heading. Moments later, two projectiles struck their target, and then a resounding explosion was heard. The DE was again bounced hard, but remained in one piece.

Pendleton headed for the site of the explosion. Oil and debris covered the water. A whaleboat was lowered to recover some of the wreck age. Among the items picked up were bottle corks with Japanese lettering, deck planking, varnished hardwood, and one chopstick.

The sinking of six Japanese submarines in 12 days by a single ship was a feat unparalleled in naval history. England was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, and the skillful employment of the Hedgehog signaled the death knell for the enemy’s undersea fleet.

Toyoda’s scouting line had been destroyed. The admiral logically assumed that the heavy American buildup at Manus and the loss of his submarines indicated a strike at the Palau Islands. He immediately sent his fleet in that direction. Two weeks later, American naval and land forces invaded the Marianas. Saipan, Tinian, and Guam were soon cut from the fabric of Hirohito’s empire.

By this time, Hedgehogs had become standard equipment on American destroyer escorts. During the month of June 1944, Banguet blasted RO-111 and Burden R. Hastings sank RO-44.

July was a banner month for DEs patrolling off Saipan. William C. Miller destroyed I-6, Wyman clobbered RO-48, and Wyman and Reynolds, operating as a team, sent I-55 to the bottom.

Proof of Concept for the New War Machine

In late September, while scouting the waters between Guam and Palau, McCoy Reynolds sank I-75. The following month, Samuel S. Miles blasted I-364, Richard M. Rowell destroyed I-362, and Whitehurst sent I-45 to the bottom.

In early January 1945, Fleming made the first kill of the year—sinking RO-47. A few days later, while patrolling as a team, Conklin, Corbesier, and Raby sank I-48. On the last day of the month, Ulvert M. Moore blasted RO-115.

The Japanese submarine force was rapidly being picked to pieces. During February, Thomason destroyed RO-55 and Finnegan sent the crew of I-370 to the bottom.

During the war, 19 destroyer escorts were awarded Presidential Unit Citations, and eight received Navy Unit Commendations. The Hedgehog had certainly proved that it could play in the big leagues.

Great stories