By Nathan N. Prefer

“But here are men who fought in gallant actions, as gallant AS ever hero’s fought,” wrote the poet Lord Byron (1788-1824). These words apply equally well to many battles fought after the poet’s death, none more so than the conquest of Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands in 1944.

For Americans of a certain age today, the name Eniwetok may call to mind a palm tree-covered Pacific coral atoll where, on October 31, 1952, the world’s first hydrogen bomb was exploded by the United States in a test called Operation Ivy Mike. But Eniwetok’s place in history began several years earlier.

By January 1944, the Americans in the Pacific had seized the offensive from the Japanese who, barely a year previously, had conquered much of the Western and Central Pacific. Under Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the Central Pacific Theater of Operations had, in the space of less than a year, completed the conquest of the Solomons and Gilbert Islands by amphibious assaults from Guadalcanal to Tarawa. By the beginning of 1944, it was time to strike at territory held by the Japanese prior to the outbreak of the war in the Pacific.

It had long been the plan of the Americans that the Central Pacific drive would require the seizure of the Marshall Islands. This island group included at least 32 islands and 867 reefs covering more than 400,000 square miles of ocean directly between the United States and Japan.

Grouped in two sections—a northeastern group and southeastern group—there were several main islands garrisoned by the Japanese that contained both naval bases and air bases, both of which threatened any Allied advance to the west. If these islands could be captured, wide lagoons at several places within the Marshalls offered the Americans excellent anchorages for their growing naval forces.

Admiral Nimitz had concerns about seizing the Marshalls. While he had requested permission from the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, D.C., to assault them, he was reluctant to incur unnecessary casualties. The islands had been under Japanese control since 1914, when they had been seized by the Japanese Navy from Germany during World War I. After the war they were handed to Japan as a part of a League of Nations Class C Mandate.

Since then, whatever defenses Japan had established in the islands remained a mystery. Although technically required to prevent “the establishment of fortifications or military and naval bases” in the islands, Japan had left the League in February 1933, and since then no foreigners had been permitted to visit them.

The Joint Chiefs approved Nimitz’s request and authorized the seizure of the Marshalls, after which Nimitz was tasked to continue on to Wake Island, Eniwetok Atoll, and Kusaie, the latter the easternmost island of the Caroline group. Technically, Eniwetok was the westernmost atoll of the Marshall Islands and would be a launching point for future operations to the west against the Caroline and Palau groups.

By October 1944, Nimitz and his staff were concerned about the Marshall Islands. Combined with the results of the recently completed Gilbert Islands operations, where the Japanese had fought from prepared positions at Tarawa, causing many casualties among the assault troops, it was decided to seize only critical islands within the group from which the others could be neutralized by air and naval strikes. Eventually, it was decided that Kwajalein Atoll would be seized, followed by Eniwetok.

Kwajalein was centrally located in the Marshalls, and from there Allied ships and planes could neutralize the other islands occupied by the Japanese. Eniwetok, scheduled for later attack, would provide the Allies with egress to the western island groups.

The target date for the invasion of the Marshalls—codenamed Operation Flintlock—was January 1, 1944. To take the two main objectives, Kwajalein and Eniwetok Atolls, a landing force composed of the Army’s 7th Infantry Division, which had fought in the Aleutians, the new 4th Marine Division, the independent 22nd Marine Regiment, and other units, was assigned to Nimitz.

On February 1, 1944, the 4th Marine Division, under Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt, took the islands of Roi and Namur in the northern Kwajalein Atoll group. Within 48 hours Japanese resistance had been overcome, and the Marines were clearing small outlying islands. To the south, Maj. Gen. C.H. Corlett’s 7th Infantry Division, facing stronger opposition, took three days to seize Kwajalein Island itself. They, too, set about clearing the many outlying islands of the atoll.

As a bonus, reconnaissance had revealed that the island of Majuro, with its enormous anchorage and potential for several airfields, was undefended. An ad hoc grouping of the 2nd Battalion, 106th Infantry, the 1st Marine Defense Battalion, and the V Marine Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company seized the atoll on January 31, 1944. The Americans had control of Kwajalein Atoll.

The quick and relatively inexpensive capture of Kwajalein prompted Admiral Nimitz to rethink his time table. The capture of Eniwetok Atoll was originally scheduled on or about May 1, 1944. From there the Americans would move to attack the Japanese bastion at Truk or other islands in the Carolines. The 27th Infantry Division, originally drawn from the New York State National Guard, was already preparing for the Eniwetok operation. Intelligence reported that the atoll was lightly defended but that the Japanese were rushing reinforcements to it daily.

Concerned that delay would only increase the difficulty and cost of the Eniwetok operation, Nimitz and his chief tactical officer, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, recommended that the Eniwetok assault be initiated immediately instead of waiting until May. Supporting this was the availability of the reserve forces that had not been needed at Kwajalein. The operation to take Eniwetok was codenamed Catchpole.

These forces were the 22nd Marine Regiment and the 106th Infantry Regiment, less its second battalion then on Majuro. The Marine infantry regiment was at this time a separate command, while the 106th Infantry Regiment was an element of the 27th Infantry Division.

Certainly no other operation in the Central Pacific had more of an impromptu character than the Eniwetok invasion. The invasion force was assembled in a week. Planning lasted less than two weeks, from February 3-15, the day the operation’s task force sailed from Kwajalein to Eniwetok. Covered by a hastily conceived American carrier strike on Japan’s major fleet base in the Pacific at Truk (Operation Hailstone), Catchpole was still believed to be a stepping stone to the invasion of the Caroline Islands.

Eniwetok Atoll is 350 miles northwest of Kwajalein. It is the typical Central Pacific coral atoll. It is 17 miles across from east to west and 21 miles long from north to south. Although there are some 30 islands within the roughly circular atoll, only three had any military value. These were Engebi in the north, Parry to the southeast, and Eniwetok in the south. Two deep-water passages into the lagoon formed by the atoll invited the American naval forces into a haven from enemy submarines.

As was the case with the other islands in the Marshall group, intelligence on the Japanese defenses was limited. Aerial photographs showed defenses but were certainly not conclusive. Initial intelligence reports placed about 700 Japanese troops on the atoll, concentrated on Engebi Island, where the only airfield lay.

By January 1944, however, reports of reinforcements began to come in that identified the 1st Amphibious Brigade as also being on the atoll. An increase in the number of defensive positions identified in new aerial photographs supported this intelligence, and estimates of the Japanese garrison were increased to between 3,000-4,000 troops.

In fact, the Americans would be facing the 1st Amphibious Brigade under Maj. Gen. Yoshimi Nishida and the 61st Guard Force under Colonel Toshio Yano. All together there were some 3,500 Japanese on Eniwetok; several hundred were not trained soldiers but rather civilians, air personnel stranded there, Korean laborers, and naval stragglers. There were actually more Japanese troops on Eniwetok than there had been at Kwajalein, and a weaker American task force was about to attack them.

The Eniwetok attack force was known as the Eniwetok Expeditionary Group, under the command of Vice Admiral Harry W. Hill, an experienced amphibious force commander. Its main components were the Army’s 106th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Russell A. Ayers (less the 2nd Battalion) and the 22nd Marine Regiment commanded by Colonel John T. Walker. Both regiments were under the command of the ad hoc Tactical Group One, commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas E. Watson, USMC.

Several supporting units were detached from the Kwajalein assault forces to assist Tactical Group One. These included the V Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company; Company D (Scout), 4th Marine Tank Battalion, 4th Marine Division; Company A, 708th Amphibian Tank Battalion; and a provisional DUKW (amphibious truck) company drawn from the 7th Infantry Division.

The 22nd Marine Regimental Combat Team included its tank company and the 2nd Separate Pack Howitzer Battalion (75mm guns), while the 106th Infantry was reinforced with the 104th Field Artillery Battalion (105mm howitzers) and Company C, 766th Tank Battalion. Several smaller units, including Underwater Demolition Team One and the 2nd Joint Assault Signal Company, rounded out the task force.

Operation Catchpole began at 9:15 am on February 17, 1944. The Japanese watched helplessly as Admiral Hill’s task force approached the atoll, firing its guns at the target islands, and then sailed majestically into the lagoon to establish a base of operations.

One of the defenders noted in his diary, “There were one man killed and four wounded in our unit during today’s fighting. There were some who were buried by shells from the ships, but we survived by taking care in the light of past experience. How many times must we bury ourselves in the sand?”

First into action were the Marines of V Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company, commanded by Captain James Jones (no relation to the novelist). They landed on two of the smaller islands and quickly reported that both were unoccupied except for natives. Other Marine units continued piling onto other small islands, covering five more without encountering Japanese troops.

Behind them, advance parties from the 2nd Separate Pack Howitzer Battalion landed and quickly set up firing positions for their guns, preparing to support the main landings. Under the cover of naval gunfire, Underwater Demolition Team 1 examined the beaches of Engebi, finding no obstacles or mines. Finally, the 4th Marine Division Scout Company seized “Zinnia,” or Bogon Island, securing one of the passages into the lagoon.

By establishing troops on these smaller islands, the Americans had prevented the Japanese from moving from island to island, reinforcing or retreating as necessary. They had also been able to establish bases for their supporting artillery that would be needed in the coming main assaults.

General Watson planned for the 1st Battalion (Lt. Col. Walfried H. Fromhold, USMC) and 2nd Battalion (Lt. Col. Donn C. Hart, USMC), 22nd Marines, to seize Engebi with Major Clair W. Shisler’s 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines, in reserve. The 2nd Separate Tank Company and an Army platoon of two self-propelled 105mm guns were kept in reserve. Both the Army and Marine artillery battalions were in support.

The Japanese on Engebi had already been battered by the U.S. Navy as reported in the diary of one of the defenders: “One of our ammunition dumps was hit and went up with a terrifying explosion. At 1300 [1 pm] the ammunition depot of the artillery in the palm forest caught fire and exploded, and a conflagration started in the vicinity of the western positions.” Worse was still to come.

Richard Wilcox, a correspondent for Life Magazine, came ashore with a group of 22nd Marines in Boat 13 and was immediately immersed in chaos and carnage: “We sprinted low through the milky surf and dropped flat on the hard coral sand…. As the men in Boat 13 lay in the coral they looked around and saw other men lying beside them, their green battle dress soaked black and the gritty sand streaking their bodies. One of these men rose to his feet for an instant, spun and then dropped on his back; the blood welled out of his chest and soaked his jacket.”

A Japanese pillbox, thought to have been knocked out, suddenly came back to life and began raking the beach with machine-gun fire. A few moments later the order was given to fall back into the water, where the only protection lay. “Not all of the men of Boat 13 reached the slight safety of the water,” Wilcox wrote. “A big, white-faced farm lad stopped crawling as a bullet went through his head.”

Eventually the pillbox was knocked out—not by artillery or tank fire, but by angry, determined Marines with nothing more than grenades in their hands.

The American landings continued as planned with the usual delays incurred by waves, wind, and mechanical failures. As Lt. Col. Fromhold’s 1st Battalion moved inland it began to encounter stiffening Japanese resistance which, supported by gunfire from the armored amphibian vehicles, slowed but did not halt the advance.

But a delayed landing by a platoon from Company A had left a gap in the Marines’ line, and retreating Japanese found it accidently while trying to escape. They soon began attacking the exposed flank of Company A, which had no resources available to stop them. Fromhold halted the battalion’s attack until a platoon of tanks could come forward and plug the gap.

Lieutenant Colonel Hart’s 2nd Battalion, meanwhile, moved inland quickly after landing despite several amphibious tractors landing in the wrong area. Tanks soon moved up behind them and the Marines swept over the airfield supported by their artillery. The Marine tanks soon encountered light Japanese tanks dug in as pillboxes, which they eliminated.

Bypassing knots of resistance, the Marines raced to the opposite shore. When regimental commander Colonel Walker came ashore at 10:30, resistance in the 2nd Battalion’s area was limited to two small areas around “Weasel” and “Newt” Points.

Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion was still engaged with the Japanese in the gap at the right of Company A; resistance from the wooded area to the front also stymied the battalion. One platoon had become separated, and casualties had been taken by the Marines. Colonel Walker immediately assigned a company from Major Shisler’s 3rd Battalion to the 1st Battalion to give it enough strength to complete its mission, and Company I soon moved through the stalled Company A.

Company I was confronted by ground thickly covered with underbrush and fallen trees that prevented observation of the enemy trenches and spider holes. The Japanese were, as usual, well entrenched in expertly camouflaged, prepared defenses; sniper positions dotted the area.

The Marines soon discovered a way to locate the enemy defenses. They found that a smoke grenade hurled into a bunker at the center of a defensive web would indicate the entire complex when the smoke escaped from the various ventilation and firing holes of the fortifications. Once the outline of the individual web was located, demolitions men and riflemen moved in and eliminated them one by one.

As they reduced the field fortifications, Fromhold’s 1st Battalion came up against “Skunk” Point, where the Japanese had built concrete pillboxes. To knock these out, two self-propelled 105mm guns from the 106th Infantry’s Cannon Company came forward. They fired an entire day’s allowance of ammunition, about 80 rounds, before knocking out the positions and killing some 30 Japanese.

With the fighting slowly subsiding, General Watson came ashore at 2 pm and soon declared the island secured. While there were many individual Japanese still hiding on the island and striking out when they could, organized resistance had ceased. Engebi Island now belonged to the Americans. Shisler’s 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines and the 22nd Regiment Tank Company were immediately reembarked to be available for the next phase of Operation Catchpole.

Meanwhile, the V Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company and Company D (Scout), 4th Tank Battalion were not idle. They continued to move to the smaller outlying islands of the atoll, making a total of eight landings, capturing one Japanese soldier, and suffering three wounded from enemy fire.

As night fell, General Watson and his staff reviewed the day’s events. Intelligence from natives and captured documents indicated that there were an additional 1,000 Japanese on the islands. There was also supposed to be a 600-man garrison located somewhere. This caused General Watson to alert Colonel Ayers that his 106th Infantry might face increased opposition as they attacked Eniwetok Island the next day. As a precaution, Watson reinforced Ayers with the 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines and the group tank company.

Back on Engebi, Lt. Cols. Fromhold and Hart were busy trying to finish off the many Japanese who had hidden underground during the battle. When night fell, the Japanese came out and began attacking the Marines on the island; the attacks were unorganized but deadly. Additionally, snipers, often lashed high up in palm trees, also made any above-ground movement dangerous.

After a formal flag-raising ceremony on Engebi the next day, February 19, the two battalions set about destroying all remaining enemy positions on the island.

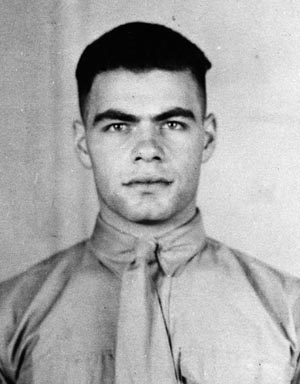

Once again, this was easier said than done. As Company E, 2nd Battalion, 22nd Marines was settling in for the night of February 19-20, 1944, Corporal Anthony Peter Damato and two of his men were on the front line. Nearly half of the company had been withdrawn in preparation for the next assault, but several small, fanatical groups of die-hard Japanese still roamed the island at night.

Corporal Damato, a former truck driver from the small mining town of Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, had already seen combat in the North African invasion where he had distinguished himself as a Marine aboard ship at Arzew, Algeria, and received a promotion to corporal. He knew his position was vital to hold the front lines for the night. When an undetected Japanese soldier crept close enough to toss a grenade into his foxhole, Corporal Damato immediately began groping for it in the pitch dark.

Knowing that death awaited all three of the Marines in the hole, he unhesitatingly flung himself on the grenade, thereby saving both the lives of his fellow Marines and their critical position in the front line. For his gallant self-sacrifice, Corporal Anthony Peter Damato received the Medal of Honor posthumously.

The invasion of Eniwetok Island came on February 19. Critical because it flanks one of the two main passages into the lagoon, Eniwetok is a long, thin spit of land. Coming ashore were the two battalions of Colonel Walker’s 106th Infantry Regiment and their supporting elements. Landings were made on the Yellow Beaches shortly after 9 am.

Amphibious vehicles filled with soldiers were supposed to carry them 100 yards inland before discharging them, but this plan soon fell awry because of a nine-foot embankment the vehicles could not cross. Worse still, the soldiers found themselves in an intricate network of spider holes like those the Marines had just encountered on Engebi. Most of Lt. Col. Harold J. Mizony’s 3rd Battalion, 106th Infantry found the going a little easier and soon reached the far shore.

Less fortunate was Lt. Col. Winslow Cornett’s 1st Battalion and a part of the 3rd. A strong enemy defense, under the command of Lt. Col. Masahiro Hashida, had been developed in the southern portion of the island—defenses that had largely been missed in the preinvasion bombardment. Hashida immediately recognized the opportunity provided by the delays in the American attack and withdrew about half his force into the prepared defenses while he sent the other half forward to harass Cornett’s 1st Battalion.

In the early afternoon some 400 Japanese troops attacked Cornett’s men. Surprise and accurate Japanese supporting fire allowed an initial penetration into the lines, but the Americans recovered quickly and pushed the Japanese survivors back into the brush.

One man, Private George Lorenz of the 102nd Engineer (Combat) Battalion, was using a pole charge to knock out an enemy pillbox when the Japanese attacked and was caught between the two opposing forces. He was forced to lie low during the battle to survive.

One of the key figures in repelling this attack was 1st Lt. Arthur Klein who, when some of the men began to retreat in the face of the Japanese attack, raced forward with his M-1 carbine held over his head and shouted, “I’ll shoot the first son of a bitch that takes another step backward! You bastards are supposed to be All-American soldiers. Now let’s see you show a little guts!”

After Lieutenant Klein stabilized Company B’s line and the machine gunners of Companies B and D who had remained in their positions cut down the remaining Japanese, the enemy resorted to mortars and long-range automatic weapons fire. Company B, now reinforced with Company K, continued pressing the enemy, wearing them down and slowly pushing them back toward their prepared defenses.

The attack continued against strong enemy positions. Colonel Ayers, concerned about the slowness of the advance, called for his reserve, Major Shisler’s 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines to land. It was to relieve the depleted 1st Battalion, 106th Infantry and continue the attack south. Shisler’s men landed by 2:42 pmand immediately moved through the 1st Battalion to take up the attack. By 6:30 pmthe Marines had reached the end of the island in their zone of action, but there remained a gap between the Marines and the neighboring 1st Battalion, 106th Infantry.

Colonel Ayers, now worried about a night attack, took the unusual step of ordering the American assault to continue during the night. But before this was necessary, Company A reached the south shore and was soon reinforced by Company B.

The following morning, February 20, the remaining Japanese on the island launched a counterattack against the Marine battalion that was soon repulsed. About 30 Japanese, emerging from an underground shelter within the Marines’ lines, managed to attack the battalion command post but were beaten off.

The Army and Marines spent the rest of the day clearing Japanese holdouts on the western side of the island. By the second night, only individual Japanese stragglers remained. The battle for Eniwetok Island was over. There remained only Parry Island to complete the campaign.

Originally the plan was to invade Parry Island at the same time as Eniwetok, but the need to commit the reserve forces to secure Eniwetok delayed the invasion of Parry. This was, in fact, beneficial since it allowed additional days of preinvasion bombardment by the U.S. Navy. It had been learned that the Japanese force on Parry Island was larger than on the other islands. So the longer the bombardment, the less opposition the Americans might have to face.

The bombardment, aided by captured maps showing the island’s defenses, was more effective than the usual preliminary bombardment. The Navy placed 944 tons of high explosives on Parry, the aviators dropped another 99 tons, and field artillery contributed 245 tons before the first Americans set foot on the island.

Relieved by the 10th Marine Defense Battalion’s arrival on Engebi, the 22nd Marines were reunited for the Parry Island assault. To reinforce the attack in light of the new intelligence concerning the larger than expected enemy strength on Parry, Lt. Col. Mizony’s 3rd Battalion, 106th Infantry and the two scout companies were added to the assault force. In addition, an ad hoc battalion of five improvised rifle companies consisting of 100 men each was drawn from the 10th Marine Defense Battalion as an emergency reserve force.

However, due to higher expenditure than expected, the assault troops were low on ammunition and weapons. The Navy ships were scrounged for additional weapons, supplies, and demolition charges. Additional materials were flown in from Kwajalein.

At 9 am on February 22, the 22nd Marine Regiment, Reinforced, still in their blood- and sweat-stained HBT fatigues from Eniwetok, hit the beaches of Parry Island. Lt. Col. Fromhold’s 1st Battalion landed on Green Beach 3 while Lt. Col. Hart’s 2nd Battalion hit Green Beach 2. Major Shisler’s 3rd Battalion was to land behind Fromhold and join in attacking south toward the island’s narrowing tail. From nearby islands the Marines were supported by the 2nd Separate Pack Howitzer Battalion and the 104th Field Artillery Battalion.

For the Japanese on Parry, waiting for the inevitable was hard. One defender wrote, “We thought they would land this morning, but there was only a continuation of their bombardment and no landing. As this was contrary to our expectations, we were rather disappointed.”

They would not be disappointed for long. The Marines stormed ashore as planned, although Hart’s 2nd Battalion landed slightly out of place. Opposition initially was light, but land mines soon took a toll of the advancing invaders. Inland of Green Beach 2, several Japanese fought to the death from individual foxholes, taking some Marines with them.

In response the Marines called forward several bulldozers, which buried the enemy alive in their holes and dugouts. Army light tanks arrived in support and detachments of the V Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company added its weight to the attack. By midafternoon Hart’s battalion was mopping up in its sector.

Not so in Fromhold’s sector, though, where Japanese resistance was stronger. Near a position known as Valentine Pier, enemy machine guns and mortars began to take a toll of the Marines’ leaders, who were exposed while organizing their troops. Hand-to-hand fighting raged along the shoreline as the Marines pushed down the island.

Japanese positions in a sand dune just inland from the beach placed interlocking machine-gun fire on any attempt to approach. Located and destroyed by mortars, artillery, and automatic weapons fire, the elimination of the sand dune defenses allowed the Marines to move inland. By 10 am two groups of Marines had crossed the island to the opposite shore. With Marine medium tanks now ashore, the advance moved forward.

General Nishida, whose headquarters was on Parry, had a surprise for the Marines. Just below the beach he had placed three light tanks. Knowing that they had no chance against the American tanks in an open fight, he had buried them in the sand up to their turrets and camouflaged them in the usual inimitable Japanese style.

However, he did not intend to use them as pillboxes, as many other Japanese commanders did. He provided ramps, so that once the Americans were close enough to prevent their naval and air support from firing, he would launch the tanks against the unprepared Americans.

Unfortunately for General Nishida, he waited just a little too long. By the time he launched his tank counterattack, the medium tanks of the 22nd Regiment Tank Company were ashore in numbers. Nevertheless, the attack did inflict casualties on Fromhold’s battalion before the American tanks could get into position to destroy the Japanese armor. By noon the Marines were on the ocean side of the island.

As the Marines were reorganizing in preparation for moving down the length of the island, they observed between 150 and 200 Japanese soldiers calmly marching single file along the shore line. It was surmised that these defenders had taken refuge on the reef off the island to avoid the bombardment and were just now trying to return to their defensive positions, unaware that the Americans had them under observation. The Marines, however, had little time to speculate. The threat was quickly eliminated by the 1st Battalion.

Major Shisler’s 3rd Battalion came ashore despite enemy small arms, mortar concentrations, and land mines. Neutralizing previously bypassed Japanese positions as they went, they soon joined Fromhold’s battalion at the advanced line. Behind them Colonel Walker and his staff came ashore and set up regimental headquarters near the beach. General Watson sent both the scout companies ashore, attaching Company D (Scout), 4th Tank Battalion to Fromhold and the V Reconnaissance Company to Hart. There was still enemy resistance to be overcome.

That afternoon, the reinforced 1st and 3rd Battalions, 22nd Marines attacked south. Japanese resistance was as fierce as ever, with the enemy fighting from spider holes, trenches, pillboxes, and dugouts. Close cooperation between infantry, armor, artillery, and supporting weapons allowed the attack to proceed steadily.

Gradually, the use of tanks, flamethrowers, mortars, and demolition charges tore apart the Japanese defenses. Armored half-tracks evacuated the wounded. DUKWs provided ammunition and other necessary supplies. By darkness the two assault battalions were within 450 yards of the end of the island. Fearing friendly fire incidents in the dark, the Marines halted for the night. At 7:30 that evening, Colonel Walker announced that Parry Island was secured.

The next day, February 23, the rest of the island was overrun. Japanese resistance was spotty but remained determined. The bypassed Japanese were later mopped up by the 3rd Battalion, 106th Infantry. Operation Catchpole was over.

The seizure of the Marshall Islands not only provided essential bases for the American advance westward, but also accelerated the overall advance of the American forces to Japan. The Navy’s assault on Truk, covering the Marshall Islands invasion, revealed that the greatly feared Japanese “Pearl Harbor” was in fact a paper tiger by 1944. The main elements of the Imperial Japanese Navy had been withdrawn, and the Americans were now comfortable with leaving it to “wither on the vine.”

Likewise, a review of the planning for future operations determined that the seizure of the Caroline Islands was no longer necessary because Kwajalein could fill meet the requirements that had earlier been thought necessary in the Carolines. Instead of adding another campaign before hitting the Marianas, the latter island group would become the next target in the Central Pacific Theater. Months of fighting and planning had been eliminated, as well as a need to incur an untold number of casualties.

Other benefits came from the Marshall Islands campaign. Despite the recent heavy losses at Tarawa, it was now clear that the basic techniques used by the Americans in amphibious warfare were sound and effective. Eniwetok would also be the last well-defended atoll the Americans would face. From this point forward, targets would be larger land masses ranging from mid-size islands like Iwo Jima to large land masses such as Leyte and Luzon.

With the knowledge that the Imperial Japanese Navy had abandoned Truk, the U.S. Navy was emboldened to strike farther and with more power at distant targets that had heretofore been considered too risky. The American fleet was also now prepared to remain offshore in support of amphibious operations as long as it took to resolve the operation, knowing it held the upper hand against any Japanese counterstrike.

Tactical innovations, such as the use of an exclusively dedicated headquarters ship for better command and control of the operation, arming landing craft with 40mm guns and rockets for greater fire support, the use of the DUKW for carrying men and supplies directly onto the beach, and landing artillery on offshore islands in advance of the main assault to better support the assault troops, were among the tactical innovations first used in the Marshall Islands.

American casualties suffered in seizing Eniwetok Atoll were 219 Marines and 94 soldiers killed in action, 568 Marines and 311 soldiers wounded in action, plus 39 Marines and 38 soldiers missing in action and presumed dead. Japanese losses were calculated at 3,380 killed and 105 captured.

Thus, for a total of 1,269 casualties, Tactical Group One had provided airfields—which were established on Eniwetok and Engebi Islands—for the U.S. Navy to stage replacement aircraft to forward operating forces about to attack the Marianas. A seaplane base was built on Parry for reconnaissance planes.

As expected, the atoll itself became a major fleet anchorage and served as the launching point for several future invasions. These islands also served as bases for the continuing neutralization of the Marshalls and Carolines, tasks largely the responsibility of the 4th Marine Air Base Defense Wing, the Seventh Army Air Force from the Marshalls, and the Thirteenth Army Air Force from the South Pacific.

For the units that took part in Operation Catchpole, the war would continue. The 22nd Marine Regiment soon formed a basis for the new 6th Marine Division and would fight again on Guam and Okinawa. The 106th Infantry Regiment would return to its parent 27th Infantry Division and fight on Saipan and Okinawa.

The V Amphibious Reconnaissance Company would be expanded into a battalion and serve in the Marianas and on Iwo Jima. Company D (Scout), 4th Tank Battalion, returned to its parent 4th Marine Division and would fight again at Saipan, Tinian and Iwo Jima. The other units that had fought for the Marshalls would also fight in other critical battles.

The battle for the small islands of the Kwajalein and Eniwetok Atolls would pay huge dividends as the war in the Pacific Theater continued.

My dad was friends with the family of war photographer, John Bushemi. He was killed on the atoll in February, 1944.

https://yesterdaysamerica.com/heroic-indiana-photographer-john-bushemi/

My father, GEORGE F. BURN served on tankers in WWII. After several convoys to Europe, he’s passed through the Panama Canal and traveled to supply Eniwetok. He spoke of this trip specifically as Japanese submarines had been driven from the pacific. They sailed alone, a long laborious three week trip.