By Allyn Vannoy

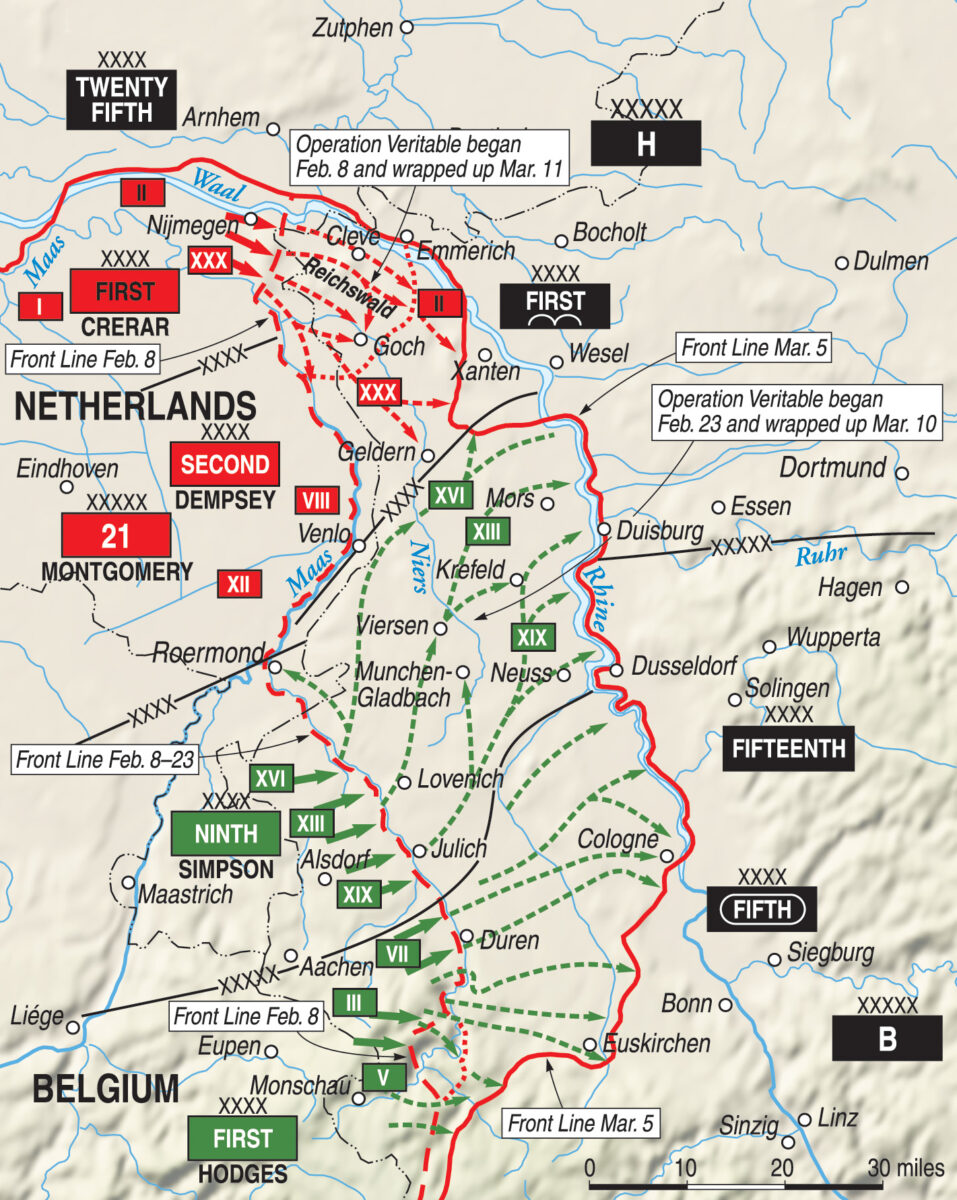

In early 1945, while the American First Army was focusing on the dams of the Roer River near the German-Belgium border and Patton’s Third Army was probing the Eifel and clearing the Saar-Moselle triangle, the First Canadian Army was about to open their offensive as part of Operation Veritable in a drive southeast up the left bank of the Rhine from the vicinity of Nijmegen. A few days later, the Ninth U.S. Army, from positions along the Roer River northeast of Aachen, was to launch Operation Grenade, an assault across the Roer followed by a drive to the Rhine.

The Ninth Army became operational on September 5, 1944, under Lt. Gen. William H. Simpson, West Point class of 1909. The Ninth had seen considerable fighting in the Brittany Peninsula in September and in the drive from the German border to the Roer River in November and early December. It was positioned on the right flank of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, just to the north of Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’s First Army.

During the December fighting in the Ardennes, the Ninth responded by doubling its frontage to 40 miles and switching to a defensive posture. By mid-January 1945, as the Battle of the Bulge was nearing an end, the Ninth Army returned to its former frontage near Aachen and prepared for offensive operations.

Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight Eisenhower concluded in February 1945: “One more great campaign, aggressively conducted on a broad front, would give the death-blow to Hitler’s Germany.” In order to deliver that death blow, Ike declared, “Before attempting any operations east of the Rhine, it was essential to destroy the main enemy armies west of the river.”

For his part, Hitler was also thinking about the Rhine and had decided on a tenacious defense west of Germany’s greatest river, with no withdrawal allowed behind it.

The broad-front advance was to be conducted by a succession of blows, from Strasbourg on the upper Rhine to Nijmegen on the lower. The first blow would be Montgomery’s Operation Veritable, intended to break through the heavily fortified Reichswald—Imperial Forest—along the German border. After that, the First Canadian Army would drive to the Rhine and then turn south, clearing the west bank and then linking up with Ninth Army as it drove northeast from Aachen.

Simpson’s offensive, Operation Grenade, was intended to be launched simultaneously with Operation Veritable. Ninth Army was to assault over the north-flowing Roer River—though threatened by the enemy’s control of a series of dams upriver—drive across the Cologne Plain to the Rhine and link up with British and Canadian forces. It was hoped that substantial German forces would be pocketed by this envelopment before they could escape across the Rhine.

The U.S. 29th and 102nd Infantry Divisions had occupied positions along the Roer since December. As a result, American commanders realized that the river presented more than the usual problems for crossing operations because the Germans controlled the seven dams at the headwaters of the Roer and its tributaries.

German destruction of the dams could cause disastrous flooding throughout the Roer River Valley with catastrophic results for any operations in progress—bridges washed away, positions inundated, troop concentrations isolated. The Allied command concluded that an attack over the Roer would only be possible after they had seized control of the dams or had blown them up and let the floodwaters subside.

Under normal conditions, the Roer averaged about 90 to 125 feet in width and was fordable at a number of points. While its current was fairly rapid at its upper reaches, it slowed near Aachen and even more along Ninth Army’s front near its confluence with the Meuse River at the Dutch town of Roermond.

The Ninth Army’s engineers estimated that a combination of spring thaws and destruction of the Roer dams would convert the river into a lake as much as a mile-and-a-half wide. Even after the waters had subsided, the Roer valley would be soft and marshy, impassable to vehicles operating off the roads. The planners selected crossing sites at the narrowest points of the river, mostly at the locations of destroyed bridges.

Captured documents indicated that the Germans recognized the destructive potential that the Roer River dams represented. It was clear that the Germans would fight stubbornly to retain control of the dams in an effort to deter Allied operations throughout the river valley.

The Germans had two options for flooding the Roer. First, they could destroy the Schwammenauel and Urfttalsperre dams, creating a flash flood throughout the valley. An engineering study by the Americans indicated that the short but high-level flood would last about eight hours, inundating the valley to 15 feet above the usual level. The engineers determined that operations should not commence until at least five days after the flood was unleashed.

The second option the Germans might employ was to destroy the outlet valves while keeping the dams intact. This would cause the velocity of the river to rise while also raising the river’s level by four or five feet. Also, some parts of the river would widen by as much as 1,200 feet. The engineers estimated that it would take at least 12 days for the river to return to normal in this case.

In an effort to remove the dams from the equation, Allied bombers were ordered to hit them during the first two weeks of December. The raids, however, proved unsuccessful. It became clear that the Germans would either be left with their options, or the Ninth Army would have to make a direct ground assault to secure the dams.

During October 1944, Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley had ordered First Army to fight its way to the area of the dams. In early November, V Corps’ 28th Infantry Division had fought itself out in the Hürtgen Forest, incurring more than 6,000 casualties in six days of fighting. Though fighting continued in the Hürtgen through November, another effort to take the dams was not made until December 13. This effort, by the 2nd Infantry Division, was barely underway when the Germans launched their Ardennes offensive.

The final attack to take the Schwammenauel and Urfttalsperre dams was ordered as Operation Grenade was about to get underway. The 78th Infantry Division, supported by the 7th Armored Division, was able to capture the Urfttalsperre dam on February 8, but they found the dam’s outlet valves had already been blown. On February 9, the Schwammenauel dam was attacked and captured, but again the valves had been destroyed.

Meanwhile, the water level along the lower Roer rose steadily, washing out some smaller dams. The river’s velocity and width increased markedly. As a result, Operation Grenade was postponed.

General Simpson believed that once the Roer dams situation was resolved, his army would be in the best position of any of the Allied armies along the West Front to penetrate the German defenses and reach the Rhine.

In attacking across the Roer River and advancing northeastward to the Rhine, the Ninth Army was to drive across the Cologne Plain—flat, open country traversed by an extensive network of hard-surfaced roads, the plain stretching from the highlands of the Eifel to the lowlands of northern Germany and the Netherlands. The only natural obstacles were two forests and two rivers—the Roer and the Erft.

The larger of the forests was in the north. Beginning on the east bank of the Roer opposite Heinsberg, it extended northward some 20 miles to the Dutch border near Venlo. This obstacle prompted Ninth Army’s planners to forego Roer crossings in that sector.

The other wooded area was the Hambach Forest, east and southeast of the river town of Jülich. When it became apparent that Simpson’s Ninth Army needed a broader base for attack, the northwestern third of the Hambach was assigned to it.

As the Roer was the line of departure, so the Erft guided the northeasterly direction of the main attack. Cutting diagonally across the Cologne Plain, the Erft splits the 25-mile distance between the Roer and the Rhine almost in half. It enters the Rhine at Neuss, opposite Düsseldorf. Neither the Erft nor the Erft Canal, which parallels the river for much of its course, were major military obstacles, but a boggy valley floor up to a thousand yards wide turned the waterway into a good natural defense line.

The Ninth Army contained 15 divisions in four corps, including the VII Corps, attached from First Army—giving the Ninth a strength of some 375,000 men. Of the divisions, only the 8th Armored Division was new to combat; the 29th Division had been in action since the D-Day landings in Normandy.

Simpson’s divisions were deployed along a 40-mile front. The northern quarter was considered unsuitable for offensive crossing operations. In the south, 10 miles east of Aachen, the VII Corps (Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins) manned positions along the Roer near the towns of Birkesdorf and Düren. Two of the corps’ four divisions were to make the initial crossing with the 3rd Armored Division held in reserve.

Opposite the VII Corps was the German LVIII Panzer Corps. To the left of VII Corps, opposite Jülich, was the XIX Corps (Maj. Gen. Raymond McLain), with the 29th and 30th Infantry Divisions and the 2nd Armored Division facing the German LXXXI Corps.

To the north of XIX Corps was XIII Corps (Maj. Gen. Alvan Gillem) near the town of Linnich, with the 84th Infantry, 102nd Infantry, and 5th Armored Divisions. On the north end of the line was the XVI Corps (Maj. Gen. John B. Anderson), consisting of the 8th Armored, 35th Infantry, and 79th Infantry Divisions, facing the German XII SS Corps. Simpson retained the 95th Infantry Division as a reserve.

In direct support of Ninth Army was the XXIX Tactical Air Command (TAC) under Brig. Gen. Richard E. Nugent, employing five groups of fighter-bombers—375 planes.

In mid-February an intensive bombing campaign targeted bridges, railways, and communications centers using aircraft of the XXIX TAC, along with the heavy bombers of the US Eighth Air Force and RAF Bomber Command.

For ground fire support, Operation Grenade had 130 battalions of field artillery and tank destroyers with more than 2,000 guns.

Facing Ninth Army was German General Gustav Adolf von Zangen’s Fifteenth Army with only 30,000 troops and virtually no armor and little artillery.

With overwhelming superiority in numbers and firepower, the Americans looked for a quick crossing of the Roer and a breakthrough of the German lines followed by a rapid exploitation into the enemy rear.

The Fifteenth Army’s three corps possessed six battered volksgrenadier divisions. Occupying the area near Düren was LVIII Panzer Corps (General der Panzertruppen Walter Krueger), with a volksgrenadier division and an infantry division bolstered by a volksartillery corps.

In the center of the line was the LXXXI Corps (General der Infanterie Friedrich Koechling), near Jülich, with two infantry divisions supported by a volksartillery corps. The north end of the line was held by XII SS Corps (Generalleutnant Edward Crasemann), with two infantry divisions. To the north of Fifteenth Army, along the Meuse River, were two volksgrenadier divisions—the 180th and 190th of the First Fallschirmjäger Army.

Von Zangen lacked reserves as all available troops were put into the line. Army Group B, the parent formation of Fifteenth Army, directed that mobile formations be placed behind the front. These included five panzer divisions—the 9th, 11th, 116th, 10th SS, and Panzer Lehr. However, most of them were committed to the Reichswald. As a result, when Ninth Army was ready to jump off, only the weak 9th and 11th Panzer Divisions remained on the Cologne Plain.

Despite the disparity of forces, von Zangen vigorously prepared for the defense of the Rhineland by creating a number of fortified lines throughout the plain.

The Germans had constructed three belts of anti-tank obstacles, minefields, and field fortifications, providing protection for the industrial centers on the Cologne Plain at Rheydt, München-Gladbach, and Neuss. But the Americans recognized that these defensive belts were likely not to be fully manned and assumed that the Germans would try to use the many villages and towns as strongpoints.

For their part, the Germans recognized the defensive potential of the Roer River positions and believed that marshy terrain would channel the enemy’s attack. Defenses were organized around terrain features as the construction of a continuous line was not possible.

Allied intelligence estimated that the Luftwaffe could field some 400 fighters and fight-er-bombers along the front, including as many as 75 jets. Realizing the possible vulnerability of bridges across the Roer to German aircraft, Ninth Army’s anti-aircraft units were directed to be vigilant.

Simpson’s plan was for the VII Corps to attack directly to the east, secure the Ninth Army’s right flank while crossing the Erft River, and capture Cologne if possible. The XIX and XIII Corps, after crossing the Roer, were to pivot to the north, striking towards München-Gladbach and Neuss, and link up with Montgomery’s troops near Gelden. The XVI Corps was to join the offensive on the third day in an effort to clear elements of the First Fallschirmjäger Army from the Meuse River valley.

Due to the destruction of the outlet valves of the Roer River dams, the American jump-off had to be postponed; American engineers recommended that the attack be delayed a week. Simpson concluded that an attack launched on either February 17 or 18 could still achieve sur-prise but would face difficult conditions. An attack delayed until February 24 or 25 would not be hindered by flooded terrain but would allow the Germans additional time to prepare their defenses.

Upstream from Düren, where the river’s banks are relatively high, the worst effect of the flood was to increase the current sharply, at some points to more than 10 miles an hour. Down-stream, along most of its length, the Roer poured over its banks and inundated the valley. Just north of Linnich, where the river is normally 25 to 30 yards wide, it spread into a lake more than a mile wide.

As a result, General Simpson set D-day for February 23—nearly a two-week delay, one day before the reservoirs presumably would be drained—still hoping to achieve some measure of surprise.

The objective of the first phase of operations was to place the Ninth Army east of Linnich with the army’s right flank anchored on the Erft River. Since this involved a wheel to the north, McLain’s XIX Corps, on the outer rim would make the longest advance, while the First Army’s VII Corps protected Ninth Army’s right flank by establishing a bridgehead around Düren, clearing the Hambach Forest, and then gaining the Erft near the town of Elsdorf.

In the second phase, Ninth Army was to extend its bridgehead north and northwest, with the main task falling to Gillem’s XIII Corps. By taking the road center of Erkelenz and clearing the east bank of the Roer to a point west of Erkelenz, XIII Corps was to open the way for an unopposed crossing of the river by General Anderson’s XVI Corps.

Given slackening resistance and firm footing for tanks, Simpson intended to quickly envelope München-Gladbach from the south and east, then drive on to the Rhine. Should the armor be road-bound or meet stubborn enemy resistance, the two corps on the left were to make the main effort, rolling up the enemy fortifications as far north as Venlo and clearing the forest area lying between Rörmond and München-Gladbach.

At 2:45 am on February 23, over 1,000 guns and mortars of all calibers of the Ninth Army commenced a 45-minute barrage. Rather than a barrage of lengthy duration, precise concentrations were focused on strongpoints, headquarters, and supply points.

Following the barrage, six infantry divisions sent assault battalions across the Roer. Each battalion carried five days’ supply of rations and gasoline against the possibility that bridging might be delayed or knocked out.

The assault troops used a combination of small boats, cable ferries, amphibious tractors (LVTs) and motor-driven double-boat ferries to cross the Roer. A platoon of engineers and 16 boats were assigned to each company of infantry. The boats were able to carry 10 men at a time as well as three engineers—who manned the boats and made the return trip.

In addition, 500 C–47 transport planes loaded with enough supplies to maintain one division in combat for one day were on call.

In order to shield the attacking infantry and bridging engineers, smoke would be employed using 4.2-inch chemical mortars firing phosphorus shells, smoke generators, or smoke pots.

Two regiments of the 102nd Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Frank A. Keating), upstream from Linnich, led the assault in the darkness.

The struggle to throw bridges across the river was discouraging. The first footbridge wasn’t completed for the 405th Infantry until almost daylight; German artillery promptly knocked it out. Another was put in about the same time for the 407th Infantry, but enemy shelling was too intense for its use.

After midday, engineers were able to open a footbridge and a support bridge. By noon, signs of an impending counterattack had begun to develop. At about 9 pm, Keating ordered every 57mm anti-tank gun in his division to cross the river.

Two miles upstream, the swollen river proved as big an obstacle for McLain’s XIX Corps as were the Germans. The 29th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Charles H. Gerhardt) was to cross around Jülich. North of Jülich, no bridges were to be built for the 115th Infantry due to floodwater, requiring the use of assault boats and LVTs.

Three miles upstream from Jülich, the 30th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Leland Hobbs) faced the most forbidding stretch of water. A patrol of the 119th Infantry crossed the river near the village of Schophoven an hour before the artillery preparation. With the patrol providing a screen, engineers began work on a footbridge as the American shelling began. A battalion of infantry then started crossing in assault boats. When a footbridge was emplaced, the rest of the regiment raced across.

The 120th Infantry, upstream, had no such success, as the current was too swift for assault boats. Plans were made for cable ferries, but the current proved too swift even for that; only 30 men reached the east bank. An anchor cable had been secured for a footbridge just before the artillery preparation began, but German artillery fire cut the cable. A second cable snapped, and a mortar shell cut a third. A fourth held long enough for engineers to construct 50 feet of bridge before the current snapped the cable and the bridge buckled.

The engineers tried once more, and the cable stayed; but the coming of daylight brought increased German shelling. It was nightfall before a footbridge was in place. The regiment resorted to LVTs to get the bulk of two companies across, with the rest of the regiment crossing on a footbridge of the 119th Infantry.

Opposite Linnich, the 84th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Alexander R. Bolling) had the good fortune to strike astride a German corps boundary. The 334th Infantry’s 1st Battalion hit the extreme north flank of the 59th Infantry Division of Koechling’s LXXXI Corps, taking the Germans by surprise and occupying the village of Körrenzig before daylight.

The battalion turned north, clearing enough of the east bank for the XVI Corps to cross unopposed. The battalion then began to roll up the flank the 183rd Infantry Division of Crasemann’s XII SS Corps. By nightfall the battalion was approaching the crossroads at the village of Baal, three miles from their crossing site, while the 335th Infantry moved to seal the 334th’s flank to the east.

As night was approaching, the Germans were able to muster counterattacks at Baal. A battalion of the German 183rd Division, supported by panzers and assault guns, drove south out of Baal at the same time the 334th Infantry was trying to break into the village. Artillery and P-47 Thunderbolts of the XXIX TAC broke up the enemy thrust. Another attack, conducted by three understrength German battalions, struck just before midnight. Fighting was intense, but by morning small-arms and artillery fire had driven the Germans off.

The day’s strongest German counteraction developed to the south against the 102nd Division. Despite that, the 407th Infantry was able to take the village of Gevenich, seizing 160 prisoners. The 405th Infantry entered Tetz, southernmost of the day’s objectives, against little opposition; but it was midafternoon before the regimental commander, Colonel Laurin L. Williams, could send a force northeast to seize the villages of Boslar, two miles from the Roer, and Hompesch. The 405th Infantry had gotten no farther than Boslar when darkness came.

The tactic for dealing with an enemy bridgehead was to launch a vigorous counterattack, but most of the German mobile reserves had been directed north to deal with Operation Veritable.

As Ninth Army’s attack had emerged during the morning of February 23, Army Group B commander, Field Marshal Walter Model, placed his reserves, the 9th and 11th Panzer Divisions, at the disposal of Fifteenth Army. General von Zangen also attached elements of the 59th and 363rd Infantry Divisions to Koechling’s LXXXI Corps.

Koechling directed an infantry battalion from each division to counterattack, with the support of remnants of two panzer battalions and an understrength assault-gun brigade. The 59th Division was to strike toward Gevenich, the 363rd Infantry Division toward Boslar and Tetz.

General Keating, 102nd Division, reacted to the counterattack on his front by ordering his reserve, the 406th Infantry, into position south and east of Tetz. The 405th and 406th Infantry Regiments formed a defensive arc from the high ground between Gevenich and Boslar, through Boslar, to the river south of Tetz. The 407th Infantry continued to hold Gevenich.

The defenders at Gevenich and Boslar had to rely on artillery and bazookas. At Boslar, the Germans attacked seven times. They first hit before 9 pm, employing a force of about 20 assault guns and panzers accompanied by about 150 infantrymen.

While American artillery fire was dispersing the panzers and infantry before they reached Boslar, some of the infantry bypassed the village and penetrated the lines of a battalion of the 406th Infantry; a reserve rifle company was able to seal off the penetration.

The commander of the defending battalion called the fight “indescribable confusion.” The infantrymen used bazookas to dispatch four Mark V panzers, but during the night panzers and infantry swarmed into the village. While the Americans huddled in cellars, forward observers called down artillery. By daylight the Germans had fallen back.

In the area of the 29th Division, the 115th Infantry had no trouble taking the village of Broich, overcoming automatic weapons and entrenched positions, to anchor the division’s bridgehead. The division’s 175th Infantry encountered little resistance in Jülich, but clearing Germans from the town was a slow process.

The 30th Division’s advance proceeded apace despite problems in crossing the flooded Roer. Leading companies of the 120th Infantry encountered an extensive anti-personnel minefield in the woods near the village of Krauthausen. Both the 119th and 120th Regiments pushed to high ground to the east. The 119th Infantry also sent a battalion against a village at the edge of the Hambach Forest and took it by mid-afternoon.

Since the 30th Division would be on the outer edge of Ninth Army’s wheel to the north, the corps commander, General Hobbs, decided to keep moving through the night. Reserve battalions moved northeast before midnight against the villages of Hambach and Niederzier, more than two miles from the Roer. Night operations were assisted as distant American searchlights bounced light off clouds, producing a twilight effect in the darkness.

At dawn, XIX Corps held all its planned D-day bridgeheads, though an unprotected right flank had developed as VII Corps had a difficult fight to cross the Roer. VII Corps was to cross the river and advance to the Erft, 13 miles from Düren, protecting Simpson’s right flank, though it would be exposing its own flank.

VII Corps (Collins) employed the 104th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Terry de la Mesa Allen) on the left and the 8th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. William G. Weaver) on the right to assault the river line.

Because Düren was a communications hub, the town was divided between the two divisions. The infantrymen were to establish a bridgehead anchored on high ground about four miles from the Roer—from the village of Oberzier to Stockheim. Collins intended to send the 4th Cavalry Group to clear the Hambach Forest while the 3rd Armored Division (Maj. Gen. Maurice Rose) passed through the infantry to gain the Erft.

The first wave of the 415th Infantry, on the north wing of the 104th Division, crossed with little difficulty. Crossing opposite Düren, the 413th Infantry’s 1st Battalion had more trouble. After the first company had crossed without opposition, German artillery and machine guns opened fire on the following troops. The remainder of the battalion shifted to the 415th Infantry’s sector to cross.

Northwest of Düren, work began on an infantry support bridge at 4:15 am, but 15 minutes later artillery and mortar shells destroyed much of the equipment and killed or wounded 19 men.

Upstream, another group of engineers had completed about 160 feet of a support bridge by 1 pm when enemy artillery scored several direct hits. At three other sites, artillery and machine-gun fire prevented engineers from starting construction until after nightfall. The first bridge wasn’t opened to traffic until midnight.

The 12th Volksgrenadier Division, LVIII Panzer Corps, failed to halt the crossing. By mid-afternoon, the 415th Infantry had drawn up to the Düren-Jülich railroad—its D-day objective. Once over the river, the 413th Infantry met light resistance at Düren and the village of Birkesdorf, where they captured an entire battalion of the 27th Volksgrenadier Regiment.

Plagued by an open right flank and German observation from the Eifel highlands, the 8th Division had the roughest day. The leading 13th and 28th Infantry Regiments were to cross in assault boats, with cable ferries and footbridges to be put in as soon as possible. The 28th Infantry’s 3rd Battalion was to open the assault, cutting enemy communications to the south and southeast by taking the village of Stockheim.

But the swift river caused trouble—only about three-fifths of the two leading companies got across. Fortunately, the crossing took the Germans by surprise. Behind a rolling barrage, the assault companies continued to the edge of woods overlooking Stockheim.

The 28th Infantry’s 1st Battalion encountered problems with failed motors, swamped boats, and enemy fire during its crossing effort. The battalion pulled back to reorganize and wait for a footbridge to be placed. During mid-afternoon, the battalion began a using a shuttle system to get the first two companies across. The rest of the battalion began crossing after dark using a cable ferry.

For the 13th Infantry, almost everything went wrong near Düren. Company K came under intense artillery and machine-gun fire; boats overturned; motors failed. Only 36 men of the 3rd Battalion were able to cross in the initial assault due to the artillery and mortar bombardment.

It was worse for the 2nd Battalion. Short rounds from American artillery knocked out four boats; another 10 were swamped. Company F put only 12 men over the river. As German fire became more intense, the battalion halted efforts to cross. A bridging company of the 12th Engineer Combat Battalion was reduced to eight men. However, by midnight, the 13th Infantry had elements of six companies across, though they had penetrated only 400 yards beyond the river.

The 28th Infantry’s 3rd Battalion, which reached the woods overlooking Stockheim, was the only unit of the 8th Division that came near accomplishing its D-day mission. This was due in part to the Germans not counterattacking its bridgehead. The next morning, February 24, the division’s engineers were able to complete a Bailey bridge at Düren.

German artillery had been extremely accurate. Several bridges were destroyed by fire despite the effort to employ smokescreens. Of some 400 VII Corps bridging engineers, 153 were casualties.

Despite swamped assault boats, swept-away bridges, and German artillery fire, all six divisions gained footholds on the east bank of the Roer by the end of the day, suffering 1,447 casualties in the process. Seven treadway and pontoon bridges were in place by dusk, allowing for the passage of vehicles and artillery to the east bank during the night.

On February 24, Ninth Army’s divisions expanded their footholds and prepared to make their wheel to the north, while VII Corps strengthened its flank. The only major change in plan was that it was agreed that Anderson’s XVI Corps need not wait to cross the Roer; instead, it would begin crossing operations the following day.

The 24th was a day for consolidating bridgeheads and adding strength—increasing from 16 to 38 battalions over the Roer. As Simpson was anxious to start the pivot to the north, both XIII and XIX Corps were to prepare to thrust forward with their right wings.

For the Germans, the 9th Panzer Division was to enter the line after nightfall, but General von Zangen had to deploy the division piecemeal. With only 29 panzers and 16 assault guns, the division was less than a formidable force.

The Germans could muster little opposition as the 30th Division drove through the Hambach Forest. At dark the division’s line ran along the north edge of the forest, tying into the 29th Division astride the Jülich-Cologne highway to the west.

The only difficulty with the Ninth Army’s pivot maneuver arose within the XIII Corps sector. The rapid D-day advance of the 84th Division, plus the failure of the left wing of XIX Corps to advance, left the 102nd Division’s right flank open.

A crippling blow struck the 701st Tank Battalion as it supported the advance of the 405th Infantry on the village of Hittorf. Anti-tank guns knocked out four tanks from one company, eight from another.

One regiment of the 84th Division remained near Baal, the northernmost point reached by the division on D-day. As the 335th Infantry moved forward, preparing the way for XVI Corps to cross the Roer, they ran into resistance. Not until mid-afternoon, after tanks of the 771st Tank Battalion arrived, did the drive on the village of Doveren pick up momentum, taking the village by evening.

The hardest fighting on February 24 fell to the VII Corps. The 8th Division had much to do before the division could be firmly established on the east bank of the Roer. The 13th Infantry, with all battalions in line, spent the day fighting through Düren. As night came, the 28th Infantry was still short of taking Stockheim, on which General Weaver intended to anchor the division’s south flank. Yet, as the second day came to an end, the 121st Infantry crossed into Düren.

To General Collins, the 8th Division’s slow progress was of minor concern so long as the bridgehead remained secure. The focus of VII Corps was the continued flank protection for Ninth Army, as well as the continued advance by the 104th Division. Collins was anxious that the 104th gain Oberzier and two other villages before the Hambach Forest, both to take out German guns on the flank of the neighboring 30th Division and to open the way to clear the forest before the Germans could concentrate there.

Because the 413th Infantry was busy mopping up in Düren, General Allen assigned the Hambach Forest villages to the 415th Infantry. Its 1st Battalion reached one of the villages before daylight but had to fight all day and through the next night to clear it.

Making a predawn attack, the 2nd Battalion reeled back from Oberzier in the face of heavy German shelling. When the 2nd Battalion moved again, it was able to take Oberzier. Because the approach to the third village was exposed to fire, the 3rd Battalion delayed attacking until after dark.

As night fell on the 24th, the conditions for committing armored cavalry were met. Anxious to get his mobile forces into action, Collins ordered both the 8th and 104th Divisions to continue attacking through the night.

Although the Germans feared an Allied pincer west of the Rhine, during the second day of the American offensive, they still did not appreciate Ninth Army’s intentions. General von Zangen hoped that Simpson was aiming his attack at Cologne and that a northward thrust was simply an effort to secure the road center at Erkelenz. The only hope for stopping the 84th Division’s drive north was to send elements of the 338th Infantry Division to Erkelenz. Against the eastward thrust, von Zangen could do nothing but urge speed in commitment of the 9th and 11th Panzer Divisions.

The position of Anderson’s XVI Corps was complicated by German bridgeheads that remaining on the west bank of the Roer—one at the village of Hilfarth, southwest of Doveren. The 79th Division (Maj. Gen. Ira T. Wyche) was to make a feint several miles downstream while the 35th Division (Maj. Gen. Paul Baade) approached Hilfarth.

To assist in the crossing, Baade sent his 137th Infantry into XIII Corps’ bridgehead to drive north along the east bank. In the hopes of keeping the Germans from demolishing a highway bridge at Hilfarth, the 692nd Field Artillery Battalion placed harassing fire around the bridge.

On the second day, 10 more infantry battalions had crossed into the bridgeheads, along with seven tank and tank-destroyer battalions and eight field-artillery battalions. Twenty bridges were constructed by the evening of February 24, providing for the increased flow of supplies and equipment to support further operations.

By the end of the day, Simpson had determined that the weakening German resistance and the expanding bridgeheads made the situation ripe for exploitation. Only along VII Corps’ front was armored commitment not feasible. In XIX and XIII Corps, the 2nd and 5th Armored Divisions were issued orders to prepare to join the battle.

A battalion of the 35th Division’s 134th Infantry attacked Hilfarth before daylight on February 26. The infantrymen forced their way into the town only to encounter mines and booby traps. By mid-morning, engineers had erected two footbridges across the Roer, and the coveted highway bridge there was secured, so that, by noon, vehicles were rolling across.

Giving XVI Corps responsibility for seizing a foothold over the Roer freed the 84th Division to concentrate on a drive to take Erkelenz. Inserting a combat command of the 5th Armored Division (Maj. Gen. Lunsford E. Oliver) on the right flank of XIII Corps also released the 102nd Division to attack Baal, while the 84th cut roads to the west.

Although elements of the German 338th Division had arrived during the night of February 25 at Erkelenz to bolster XII SS Corps, their efforts proved weak. On the 26th, the 102nd Division found Erkelenz deserted.

XIX Corps found resistance increasing as von Zangen committed portions of the 9th and 11th Panzer Divisions. But just before dark on the 25th, the 30th Division’s 117th Infantry broke the resistance of panzergrenadiers at the village of Steinstrass, while the 119th Infantry bypassed the village. The 119th ran a gantlet of heavy fire that knocked out eight supporting tanks, but took over 200 prisoners, including a nebelwerfer (rocket mortar) company.

During the day, the 29th and 30th Divisions rolled up the flank of the German second line of field fortifications, the 29th advancing four miles to the Erft while the 30th advanced more than three miles.

Exploitation seemed at hand, but General McLain was reluctant to turn the advance over to his armor lest the Germans had manned their third defensive line, which ran through the village of Garzweiler, roughly on an east-west line with Erkelenz. McLain directed the 30th Division to continue as far as Garzweiler, whereupon the 2nd Armored was to take over.

The hardest fighting occurred on the approaches and within the southern reaches of the Hambach Forest. The 9th Panzer Division’s 10th Panzergrenadier Regiment could give only slight pause to a relentless American push.

Making a night attack along the Düren-Cologne railroad, a company of the 413th Infantry took 200 prisoners, all that remained of the 1st Battalion, 10th Panzergenadier Regiment. At the same time, the 8th Division’s 13th Infantry was wiping out the last resistance in Düren. In an attack on a village two miles to the east, two battalions of the 121st Infantry fought all day on February 25 without success, until the Germans pulled out.

While his two infantry divisions continued to drive forward through the night, General Collins ordered his cavalry and armor across the Roer.

With the 13th Infantry attached, the 3rd Armored Division was split into six task forces. Two from its Combat Command A (CCA) were to attack astride the Düren-Cologne highway to gain the Erft River. CCB, also with two task forces, was to take the road center at Elsdorf, northeast of the Hambach Forest. One task force was placed in reserve, while the 24th Cavalry Squadron was to protect the division’s left flank inside the Hambach Forest.

Striking northeast, the American armor turned away from the area of the LVIII Panzer Corps to that of the LXXXI Corps, where the 9th Panzer Division had arrived. Also present was a kampfgruppe (battle group or task force) of the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division, rushed from the Eifel. Yet, little could be done against the Americans.

In moving up the Düren-Cologne highway, CCA lost eight tanks to antitank guns. As night came, contingents of CCB were drawn up before Elsdorf, ready to hit the village the next morning.

During February 25-26, the American infantry divisions had advanced to the northeast at two to three miles a day as the German defenders gave ground grudgingly. By the end of the 25th there were indications that the German front was near collapse. In the south, the 3rd Armored Division had entered the battle and crushed the 12th Volksgrenadier and 9th Panzer Divisions.

On February 27, surviving elements of the 9th Panzer Division made a stand in Elsdorf. But with fire support from a company of tanks, an infantry battalion of CCB broke into the town before noon and began mopping up. By mid-afternoon Elsdorf was sufficiently cleared to enable General Rose to commit his 3rd Armored Division toward the Erft. As night came the armor held a three-mile stretch of the Erft’s west bank.

During the day, VII Corps completed its role in Operation Grenade. It had covered ten-and-a-half miles from the Roer bridgeheads to the Erft to seal Ninth Army’s south flank.

The operation continued to aim at crushing the southern wing of German Army Group H against Operation Veritable while encircling the First Fallschirmjäger Army and elements of the Fifteenth Army that could be forced to the north.

On the 26th, the German Commander-in-Chief West, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, pleaded with Berlin to allow him to pull the First Fallschirmjäger Army out of a salient at the juncture of the Roer and Maas Rivers near Roermond, but Hitler refused.

The next day, Simpson approved commitment of his armored divisions in a shift to an exploitation phase. Simpson did question whether his infantry should continue to lead the way for the XIX Corps until it passed the German trench system, gambling that the enemy was no longer capable of an organized defense. He did direct McLain to send his armor through to the Rhine at Neuss.

On February 27-28, Ninth Army’s armored forces—the 2nd, 5th, and 8th Armored Divisions—were unleashed as operations shifted from breakthrough efforts to pursuit. Simpson ordered that there be no letup that would permit the Germans the opportunity to regroup.

The 35th Division, with the attached 784th Tank Battalion, advanced 15 miles on March 1, seizing the fortified town of Venmo on the Meuse. At the same time, XIII Corps neared the towns of Krefeld and Ürdingen on the Rhine, while the 175th Infantry Regiment, 29th Division, captured München-Gladbach. To the south, Rose’s 3rd Armored Division attacked toward Cologne, seizing the Vorgebirge—a commanding ridge west of the city.

Simpson shuffled his reserves, placing fresh troops with each corps in order to maintain pressure—the 75th Division (Maj. Gen. Ray E. Porter) to XVI Corps, the 79th Division from XVI Corps to XIII Corps, and the 95th Division (Maj. Gen. Harry L. Twaddle) attached to XIX Corps.

For the Germans, the Panzer Lehr Division was ordered to counterattack southeast from near München-Gladbach to link up with the 11th Panzer Division. But the Panzer Lehr was still assembling. The XII SS Corps continued to fall back to the north while LXXXI Corps and the remains of the 9th and 11th Panzer Divisions withdrew behind the Erft.

McLain’s XIX Corps inserted the 83rd Division on the right of the 2nd Armored with the mission of capturing Neuss and securing Rhine bridges at Neuss and at Oberkassel. Attacking in the early afternoon, the 83rd continued through the night, clearing Neuss, but found all three bridges there destroyed.

On the evening of March 1, a task force composed of units from the 330th Infantry, 736th Tank Battalion, and the 643rd Tank Destroyer Battalion (self-propelled) attempted to seize the Oberkassel bridge. The American tanks, painted with German colors and markings, accompanied by German-speaking GIs in German uniforms, were able to work their way through German lines. Although they rushed the bridge with some of the tanks, even occupying its western end, the Germans demolished it.

Four Rhine bridges remained in the Duisberg area, near the confluence of the Rhine and Ruhr Rivers. Another span was located near Uerdingen, four others connected Neuss and Oberkassel with Düsseldorf, and one remained at Cologne.

The 5th Armored Division advanced against little opposition until, shortly past noon, they were able to link up with the 2nd Armored Division just south of Krefeld.

The 84th Division’s 334th Infantry launched its attack at 2 pm, with the intention of passing around the north side of Krefeld to reach the Krefeld-Ürdinger Bridge. With attached tanks, the head of the column got into Krefeld less than two hours after jump-off, where they became involved in a firefight with German anti-tank guns.

The task of capturing Ürdingen and the still-standing bridge passed to XIX Corps, as-signed to the 2nd Armored Division’s CC with attached battalions of the 95th Division’s 379th Infantry.

By March 2, units of the Ninth Army had reached the Rhine at several points as German forces disintegrated. Simpson directed his army to continue its advance to the north and north-east in order to eliminate any resistance between the Rhine and Maas Rivers from Neuss to Rheinberg, seize Rhine bridges wherever possible, and provide assistance to the First Canadian Army.

The Germans moved to form a bridgehead west of the Rhine extending north from Ürdingen, west to Geldern, and on to Xanten with bridges to their backs. The 2nd Fallschirmjäger Division was ordered to the bridgehead, but it consisted of only three or four understrength battalions.

The 2nd Armored Division was to attack toward the Ürdingen bridge at 0200 hours on 3 March. In preparation, the 92nd Armored Field Artillery Battalion kept up a continuous harassing fire for more than 15 hours. During the assault, four tanks were knocked out, blocking the passage of those following, while the infantry was halted by heavy mortar fire.

After dark, a patrol gained the bridge and began cutting wires to demolition charges. But at 7 am the next morning the Germans were able to blow the center and west spans, denying the bridge to the Americans.

Fighting to clear Ürdingen continued throughout March 4th and into the 5th. At the same time, General McLain ordered the 95th Division to drive for the bridges at Rheinhausen, north of Ürdingen. But artillery observation pilots reported that both bridges there were already down.

In the VII Corps sector, the 3rd Armored and 104th Infantry Divisions entered Cologne on March 4 against sporadic resistance. But the Americans found that the Hohenzollern Bridge over the Rhine had been blown up the previous day.

In breaking through at Ürdingen, XIX Corps had compromised the bridgehead line that General Alfred Schlemm, the First Fallschirmjäger Army commander, had been attempting to hold. Army Group H authorized Schlemm to withdraw to a smaller bridgehead at the confluence of the Ruhr River with the Rhine at Duisburg.

On March 5, as XIX Corps finished clearing the Rhine’s west bank in its sector, the 5th Armored Division, XIII Corps, dashed towards Orsoy. With tanks and halftracks, CCR covered the last two miles into Orsoy, cutting through German infantry and overrunning artillery. The 84th Division cleared Moers and Homberg but found the Rhine bridges at Duisburg already destroyed.

Although the Americans had failed to secure a bridge over the Rhine, the speed of their advance and vigor in the attack had shattered German defenses. Those German units that had managed to escape across the Rhine were demoralized and spent. Collins’ VII Corps alone captured 13,000 Germans during its advance.

Some 50,000 German troops still remained on the west bank near Wesel. The “Wesel Pocket” held out for four days, with most of the troops reaching the east bank of the Rhine before both bridges there were destroyed on March 9.

With the departure of the German troops from the Rhine’s west bank, Operations Grenade and Veritable were concluded. Grenade took 30,000 German prisoners and killed an estimated 6,000 more while suffering 7,300 casualties.

In just over two weeks, Simpson’s Ninth Army had driven over the Roer to the Rhine and cleared the west bank of the Rhine from Düsseldorf to Wesel. Flexible Allied planning, combined with rigid German defensive actions, had made Ninth Army’s victory inevitable.

Sad there wasn’t any photos of the 95th Infantry Division.

Doc