By Nathan N. Prefer

By January 1942, Britain was still in the fight of her life. Germany had occupied all western Europe, controlled the Mediterranean, and was threatening British colonies in North Africa. German submarines all but controlled the North Atlantic, threatening to starve Britain into submission.

German battleships now positioned at Brest, France, threatened to make a final cut of Britain’s lifeline to its dominions. The only bright spot was the fact that the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor had brought the United States into the conflict on the side of the British. That, and the successful defense of Britain itself by the Royal Air force, had kept Britain in the war.

One of the few advantages Britain’s armed forces had enjoyed in the early days of the war had been radar, which allowed them to see the enemy before they were seen by that enemy. This had been a major advantage during the Battle of Britain, in the hunt for the German battleship Bismarck, and other early battles. But this January, British scientific intelligence had reported that there were indications that the Germans were now deploying new radar stations and adding radar to their ships and aircraft.

Radar stands for “radio detection and ranging.” It is a system of bouncing radio waves against an object and measuring its rate of travel to determine targeting information. Before the war, development of this new detection method had been underway in Britain, the United States, and Germany. But it was the British who first put it into use during World War II, in 1939. They had first developed the “Chain Home Early Warning System” by establishing land-based stations that had proven crucial to the success of the aerial defense of Great Britain in 1940-1941. Within a few years it would be used on land, sea, and in the air.

Early radar sets were large, cumbersome, and unwieldly, preventing their use on ships and aircraft. But the British devoted considerable resources to continuing development of radar and would eventually produce radar sets for all manner of ships, aircraft, and land stations. Known at this stage of development as Radio Direction Finding (RDF), the British did not believe that the Germans had their own RDF sets. Radar was eventually fitted to night fighters, enabling Britain to counteract the German night bombers over their cities. Shipborne radar was also a reality early in the war for the British, and later the Americans. Allied aircraft fitted with radar would soon make a significant impact against the German submarine menace, finding enemy submarines even when the naked eye could not see them. Soon warships would have their guns controlled by radar, ensuring greater accuracy and more successful kills.

It was known in Britain that the Germans were developing radar and that some of their larger warships had been equipped with it. It was known to the Germans as Dezimeter Telegraphie, or “D/T.” But in January 1942, evidence that the Germans were installing a new type of radar along the French coast caused a stir in the highest levels of British military circles. If the Germans successfully developed a defense against the nightly raids of Bomber Command, then Britain would have no offensive power against a still aggressive Germany. Indeed, at this time Britain’s only means of striking back at Germany were the nightly bomber raids launched from England against German targets on the continent. These, and the occasional commando raid, were all that Britain could do at this stage of the war.

At this point in the war Britain was losing, on average, four bombers for every 100 bombers sent out each night. This was a significant loss factor for a nation with limited resources, and any increase would threaten Britain’s chances of continuing to harass Germany until a major offensive could be developed. In the interim, much of British war production was being channeled into Bomber Command, and any threat to the bomber offensive also threatened British war production.

The British had already targeted the early German radar units, known as the “Freya.” After much study they could locate it, listen to it, and when they wished, jam it. At times, they could even feed it false information, making it work for them. But recently there had been evidence of a new German radar, unknown to the British, that had the capability to locate a bomber, lock onto it, and lead German night fighters and/or antiaircraft guns to it. This was a new threat that needed to be addressed. It appeared to be small and apparently easy to manufacture. But little else was known about it.

Two leading scientists researching German radar capability, Professor Frederick Alexander Lindemann of Oxford University and Dr. Reginald Victor Jones who was working on the Royal Air Force Air Staff, both proposed that something be done to acquire one of these new radar devices for study by the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE). To achieve this goal, Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, the recently appointed head of Combined Operations, the British Commando organization, proposed a raid into occupied France to capture a new German radar set.

Initial reaction to the proposal was disappointing. Although Air Marshal Henry Portal, the chief of the Royal Air Force, expressed interest, neither the Royal Navy nor the British Army were excited by the proposal, as it was felt that the benefit would mostly fall to the Royal Air Force. However, when the proposal reached the ears of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who favored it, things changed.

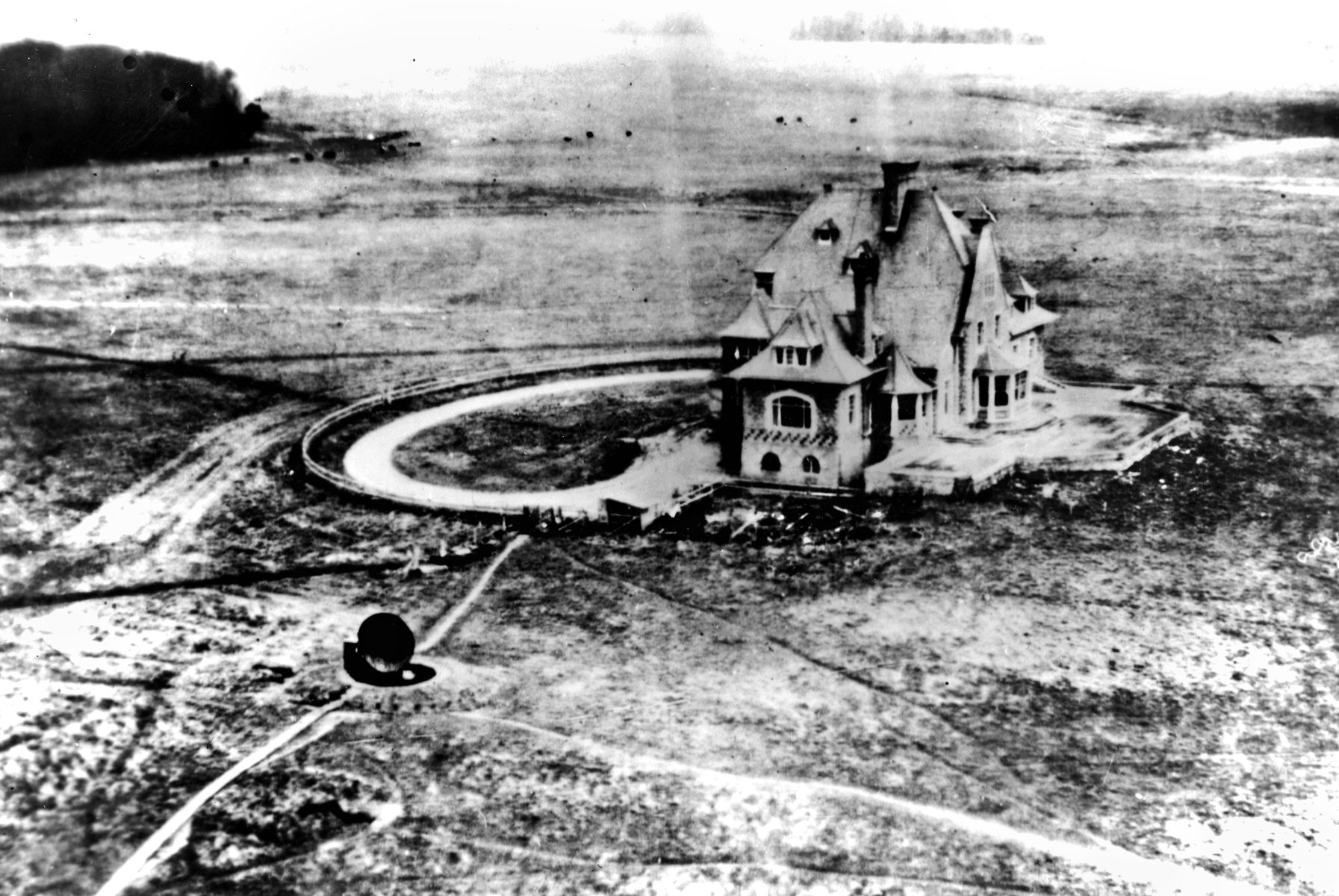

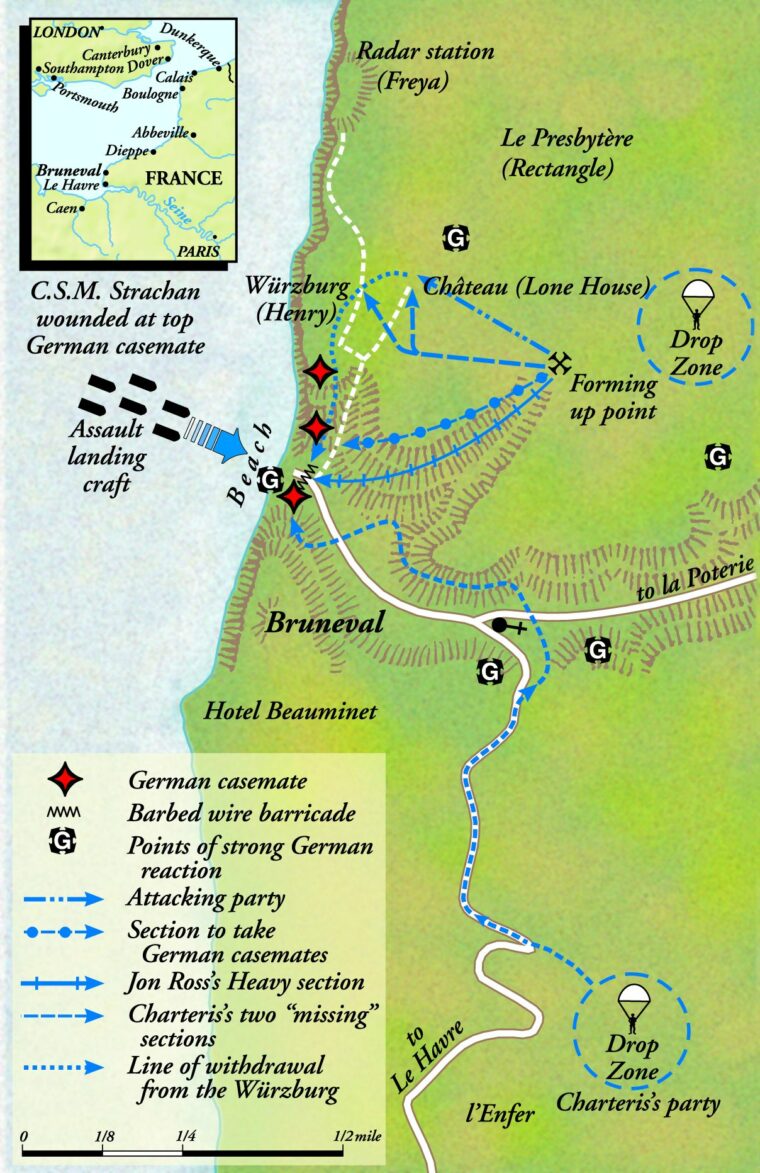

The first step was to choose a target. Due to the skill of the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit of the Royal Air Force, one of the new sets was identified and photographed in detail atop a cliff on the French coast at the small village of Bruneval, 12 miles north of Le Havre. Dr. Jones and his staff at TRE were anxious to get a look at the insides of the new German radar. They turned to Admiral Mountbatten.

Admiral Mountbatten kept the operation simple. He decided that only a minimal force should be dispatched to seize the vital parts of the new radar, so as not to draw too much attention to the operation by the enemy. He decided on using one company of the Parachute Regiment, a squad of Royal Engineers, some radar mechanics from the Royal Air Force, and a squadron of Whitley bombers to drop the parachutists. Light naval forces would take the raiders back to England when the job was done.

Planners had learned that Bruneval was in a ravine which ended in a cliff-encircled beach which in turn was guarded by several pillboxes. This indicated that an evacuation by sea was feasible. Using both the photos taken by the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit and information coming from the Free French underground a plan was developed. Now they needed to find the men to do the job.

The first step was to get the paratroopers. Major General F. A. M. “Boy” Browning, the leader of Britain’s airborne forces, assigned the newly formed 2nd Parachute Battalion, to the mission. In turn, the battalion commander assigned his adjutant, Major John Frost, to command the parachute portion of the raid. The battalion, newly formed and still training, consisted of three companies. Of these, it was considered that Company C was the most efficient. Major Philip Teichman commanded the company, but because he was an Englishman, and the company was filled with Scottish soldiers, it was decided that if Major Frost could complete his required number of parachute jumps in time, he would command the company on the raid. Major Frost, himself a Scot, was more than willing. If, for any reason, Major Frost became unavailable, then Major Teichman would command the company on the raid.

There was some trepidation about this raid within the airborne community. There had been one prior raid using airborne troops. Some weeks earlier a group of parachutists had been dropped into southern Italy to destroy an aqueduct. None of them had been heard from since. It was hoped that they had been captured and were enjoying German hospitality in some prisoner of war camp, but no one knew for sure what had happened to them. The aqueduct had not been destroyed.

With only hours to spare, Major Frost completed his required jumps to qualify as a British parachutist, much to Major Teichman’s disgust. Frost joined Company C, which was then sent to a camp in the south of England. Here they were inspected by General Browning, whom Frost knew from the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. Major Frost was somewhat concerned about his men’s appearance. “At that stage of the war clothing and equipment were scarce, and for a few months we had been concentrating on toughness and on weapons and parachute training. We’d had little time for drill, and still less for making ourselves look glamorous, or even clean. After a prolonged and uncomfortable railway journey, the Jocks had found time to work the dreadful Tilshead mud deep into the fabric of their uniforms. They looked horrible.”

But General Browning, instead of admonishing Major Frost, ordered him to give the General’s adjutant a list of new uniforms and other gear needed by the company, which was soon provided. Another problem arose when Prime Minister Churchill learned that the raid was to be carried out by parachutists. He had always favored seaborne raids. To convince him of the practicality of an airborne raid, Company C put on a demonstration on the Isle of Wright.

Company C of the 2nd Parachute Battalion was to simulate a raid on enemy positions. This was to take place in front of the Prime Minister and the War Cabinet. They were to parachute onto the Isle of Wright, then seize the objective before being evacuated by sea. Soon thereafter, Major Frost was told to get his men in the best shape possible and that they had a secret mission planned for some time in February, but which he could not be told of at this time. Major Frost immediately objected to not being able to plan the operation with his own battalion staff. But secrecy prevailed, and despite feeling “blackmailed,” Major Frost agreed to accept a plan in which neither he nor his officers had any part in developing. Even then, other than the basic outlines of the operation, he was told nothing, particularly that the target was a German radar installation.

That target was one of the new German “Würzburg” radar sets. Development began in 1936, and by 1942 the set proved more accurate than the earlier Freya type. Further, it could follow any fast-moving target, such as a bomber, was simple to handle, and was far more reliable. It was tough, durable and could be mounted on four wheels which retracted when it was put into action. When it was first introduced to the German hierarchy, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring had been the one most interested in it, for it promised a far more accurate antiaircraft defense for Germany, one that he had promised would never be challenged by any enemy bomber.

But precisely because of his promise, the Reichsmarschall never ensured that the radar set would be mass produced. Neglect and production problems delayed the development and distribution of the new radar, and as a result it was not a decisive weapon for the Germans. Not until later in the war did it show its value when it was paired with German night fighters to locate and attack night bombers over Germany.

On February 1, 1942, Sergeant C. W. H. Cox was employed as a radar mechanic. His hobby of ham radio had qualified him for the job, and by this point he was considered one of the best radar mechanics in Britain. On this date he was given a special pass and ordered to report to the Air Ministry. Upon arrival he was directed to the office of Air Commodore V. H. Tait. There he was told that he had volunteered for a dangerous job. Stunned, Sergeant Cox replied that he “never volunteered for anything.” Unpleasantly surprised by Sergeant Cox’s reaction, Commodore Tait responded with, “But now you’re here, Sergeant, will you volunteer?”

When Sergeant Cox asked what he would be volunteering for, he was told it was top secret and that he could not be told what the mission was just yet. Despite not getting an answer to his logical question, he volunteered. Promoted to flight sergeant, he was sent out again, this time to Manchester, and told to report to a training school at nearby Ringway. When he learned that this was the Parachute Training School, Flight Sergeant Cox’s immediate reaction was, “Let me out of here.” But instead he spent the next 12 days learning how to parachute.

Given yet a third pass to report to the 2nd Parachute Battalion training area, he first met Major Frost and his second-in-command, Captain John Ross. Now this “volunteer” found himself undergoing physical training, marching, weapons training, knife fighting and scaling barbed wire. Slowly it began to dawn on Flight Sergeant Cox that these paratroopers were preparing for some sort of a raid and that he was destined to accompany them.

As if to confirm his thoughts, he soon learned that he would be attached to a squad of Royal Engineers under the command of Lieutenant Dennis Vernon. What his personal role was to be was soon made clear to him when he was told to use a loaned British radar set and instruct the Royal Engineers what it was and how it worked. As more of the plan became known to the participants, Flight Sergeant Cox learned that he and another radar technician were to land by parachute somewhere in France, along with the paratroopers and Royal Engineers, and then dismantle a German radar set.

The second radar technician had been injured during the parachute training phase, and rather than waiting for another volunteer, Flight Sergeant Cox suggested that Lieutenant Vernon be the second radar expert, since he had been especially adept at the radar training. This suggestion was acceptable. In the final plan, four Royal Engineers would adopt an anti-tank role, while the other six, plus Lieutenant Vernon and Flight Sergeant Cox would dismantle the German radar set. Lieutenant Vernon, who had some experience, would also be the mission’s photographer, taking photos of the German set.

Meanwhile, the paratroopers of Company C were enjoying their celebrity status. In a period when getting any supplies or equipment was difficult, they were given anything they asked for, and more. When the supply sergeant requested nine Bren guns for the company, 18 were received. New uniforms, boots, binoculars, pistols, flashlights, and other items were quickly made available to the company. They were among the first to receive the new British automatic weapon, the Sten gun. Radios were provided for each platoon, and two extra sets were provided “for contact with the Navy.”

As the preparations neared their end, a new member of Company C was introduced by higher headquarters. This man was introduced only as “Private Newman” and was put on the book of Company C as one of their members. Described as a translator, he spoke perfect German and English. He seemed to have been a world traveler, having lived in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, New York, and London. For a while, Major Frost had his doubts about “Private Newman,” believing him to be some sort of a fifth columnist. Private Newman’s arrival brought Company C up to a strength of 120, including the engineers and Flight Sergeant Cox. It was time to move.

The raiders next went to Scotland. Here they boarded the Royal Navy’s transport HMS Prinz Albert, a ship originally of the Belgian government. They practiced getting aboard from a rock-strewn coast, which was far more difficult than first expected. In bad weather, it was near impossible. After some days, Admiral Mountbatten came to see their progress and discuss plans with the leading officers. It was only then that the Royal Navy learned that their “guests” were parachutists who would soon be boarding their ship from the shores of occupied France, if all went well.

The following day the parachutists and the Navy parted, each going their own way. The airborne returned to their training camp while the HMS Prinz Albert sailed for Portsmouth. One more training display, this time for General Browning, was conducted. Major Frost had reservations about jumping from bombers, for they had neither experience nor training for such an operation, but the display went perfectly, without error or jump casualties.

It was then that the Germans put a scare into the raiders and their planners. The large German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau along with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen executed Operation Cerberus, their “Channel Dash” from Brest on the French coast up the English Channel to Germany. This clearly indicated a tenuous British control over the English Channel, which the raiders would have to cross to return to England with the captured radar set. Then the final exercise went badly. The drop was wide, with many equipment containers landing away from the paratroopers. The folding trolley, designed to carry the radar set from the cliffs to the beach, was also dropped in the wrong place. Finally, the boats waiting to evacuate the raiders waited at the wrong beach. Major Frost was concerned.

There were only two days left before the scheduled raid. Tide and moon conditions required that it be conducted between February 23-27. With the bad display of the exercise before them, the naval authorities insisted on one more trial run before executing the actual raid. Bad weather cost them one day, and on February 22, despite foul weather, the evacuation exercise went reasonably well.

Major Frost was under orders to “Capture various parts of HENRY and bring them down to the boats. To capture prisoners who have been in charge of HENRY. And to obtain all possible information about HENRY, and any documents referring to him which may be in LONE House.” Henry, of course, was the actual radar set, while the lone house was a chateau just behind the radar site used by the Germans as a headquarters and billet. Over Major Frost’s objections, the planners had divided his team into three assault groups of equal size. These were to drop on Bruneval at five-minute intervals starting just after midnight.

The first group, codenamed “Nelson,” was to drop first and move to the beach. When given the signal by Major Frost from above, they were to attack the German defenses on the beach, securing the raiders’ line of retreat. “Nelson” was commanded by Lieutenant E.C.B. Charteris, joined by a heavy weapons section under Captain Ross. Again, Major Frost was concerned. They had no idea how many Germans manned the beach defenses, what weapons they were armed with, nor if any reinforcements were nearby.

The second group, codenamed “Drake,” was to split into four sections. Twenty men under Lieutenant Peter Naumoff were to move against a big farmhouse at Le Presbytére and block any German attempts to attack from that area. “Hardy,” a group of five men under Major Frost, would surround the chateau. Another party of 10 men, “Jellicoe,” under the command of Lieutenant Peter Young, would surround the radar itself. Lieutenant Vernon and his Royal Engineers, with Flight Sergeant Cox, would then enter the radar installation after Lieutenant Young’s men had cleared it of the enemy. A final group, “Rodney,” of 40 men under Lieutenant John Timothy, would drop last and guard the entire operation from the landward side, acting as a reserve and rear guard when the time came. All these groups were to get into position as quickly as possible and then await Major Frost’s signal, four blasts on a whistle, to attack.

There was also supposed to be one other landing. This was “Noah,” a civilian radar specialist whose real name was D. H. Priest, who was to land from the boats and rush up the beach to help with obtaining the radar and documents about it. If he did indeed arrive as planned, it would mean that the evacuation boats were ready and waiting.

The raiders moved out of their camp late on Monday, February 23 and packed their equipment containers, ready to leave for the airfield. But as they did, a message came from headquarters. Weather conditions had cancelled the operation for today. It was postponed until the next day. But on Tuesday it happened again. And on Wednesday. And on Thursday.

One observer wrote, “We are all thoroughly miserable. Each morning we brace ourselves for the venture, and each night, after a further postponement, we have time to think of all the things that can go wrong, and to reflect that if we don’t go on Thursday we shall have to wait for a whole month to pass before conditions may be suitable. After all, the weather in the English Channel in February and March is not inclined to be ‘suitable.’”

By Friday, although the weather had improved slightly, Major Frost expected orders to go on leave until the next opportune weather arrived. But a consultation between the services involved had resulted in an agreement to wait and see what this day might bring out in the channel. After four days of rising expectations, most of the raiders were disappointed. But Major Frost seemed excited, expecting some sort of action. And soon General Browning appeared to announce that the raid was on. The Royal Navy issued its own orders to the HMS Prinz Albert, “Carry Out Operation Biting Tonight 27 February.”

Reluctant volunteer Flight Sergeant Cox, described the preparations. “We were put in blacked out Nissen huts. Inside it was warm and the light was yellow. Parachutes were laid out in rows on the swept floor and we each picked one, hoping that the dear girl who’d packed it had had her mind on the job. These were dark ‘chutes, camouflaged in greens and blacks. Until then I’d only used white or yellow ones. They pressed bully [beef] sandwiches on us, real slabs, and mugs of tea or cocoa laced with rum. We checked each other’s straps, and wandered about wide-legged, like Michelin men.”

Led by a Scottish piper playing various Scottish regimental marches, the men moved out in “sticks” of 10 to the aircraft. The dozen Whitley bombers were waiting for them. The paratroopers boarded the aircraft and awaited takeoff. “We put on our silk gloves and crawled into sleeping bags for warmth. The Whitley’s ribbed aluminum floor was fiendishly uncomfortable. Ahead we could hear a kite [plane] revving prior to take-off and then it was away. Others followed until it was our turn. The whole machine throbbed and bumped and dragged itself off the ground as though it had great big heavy sloppy feet. Nobody slept in that dim-lit metal cigar,” recalled one participant.

In the English Channel the HMS Prinz Albert had dropped her landing craft and was headed back at best speed to Portsmouth. Escorted by motor gunboats (MTBs), the landing craft headed for the beach below Bruneval under their own power. The weather so far was good, with light wind, good visibility, a bright moon, and some haze.

Above them the dozen bombers flew over the English Channel. Crew members opened the hatch, a hole in the floor of the bomber, and a blast of cold air entered the planes. Major Frost sat on the edge of his hatch with his feet dangling into the air. Antiaircraft fire sparked the air below and around them as they flew into French airspace. Then came the command, “Go!”

Major Frost jumped, and his parachute opened immediately. He was pleased to look around and recognize many of the landmarks he had been briefed to expect. The sudden quiet also struck him, after the noise of the flight. Then he was in the snow on the soil of France. It was time to get on with the raid.

Flight Sergeant Cox had also come down as briefed and was even more pleasantly surprised to see two objects land near him. One was an equipment container and the other the hand-trolley without which they would have great difficulty in moving the radar. Neither had been damaged by the drop.

Major Frost took one look at the paratroopers following his group and knew instantly that any chance of surprise had been lost. They were clearly outlined in their parachutes by the bright moon. He also assumed that the radar that was their target had tracked them inbound and knew they were coming. The only surprise left was how, when and where the attack would come. But then things began to go wrong.

Captain Ross reported that two whole sections of the men assigned to clear the evacuation beach had not arrived. Twenty men were missing. Had the planes been shot down? Were the men mis-dropped elsewhere? Major Frost directed Captain Ross to wait a few moments longer for the arrival of the missing Lieutenant Charteris and his men. If they did not arrive soon, then it would be up to Captain Ross and his heavy weapons unit to clear the beach on their own.

Major Frost then concentrated on his main targets, the radar set and the chateau. After all groups, except Lieutenant Charteris’s men, had arrived and formed up, each was sent off on its assignment. Lieutenant Young made for the Würzburg, Major Frost and Private Newman for the chateau, and the protection group for the interior. Following Lieutenant Young were Flight Sergeant Cox, Lieutenant Vernon, and his engineers pulling the trolley behind them.

Major Frost’s arrival at the chateau was greeted with an open door. The interior was dirty, empty and without any furniture. Behind him Major Frost could see that Lieutenant Young’s party was surrounding the radar, and he blew the four whistle blasts signaling the opening of the attack. As soon as the fourth blast went out, Major Frost and his small group entered the house. The first floor was empty, but shots came from above. They charged up the stairs and found one lone German firing at them. He was killed, and they searched the rest of the building. It was empty.

Lieutenant Young’s group attacked the radar installation, quickly dispersing a few Germans who were located there. One ran for the cliff, and Lieutenant Young ordered his men not to shoot since they had yet to take a prisoner, a part of their assignment. The escaping German soldier fell over the cliff edge but managed to grab a hold and stop his descent. He was rescued by the paratroopers and captured.

Lieutenant Vernon had gone ahead of his group to reconnoiter the radar installation after the Germans had dispersed. He called forward his group, and they easily jumped over a low barbed wire entanglement protecting the site. As Flight Sergeant Cox and the engineers inspected the radar equipment, Major Frost appeared with Private Newman who immediately began to question the prisoner. Firing was suddenly heard from the direction of Lieutenant Naumoff’s group. More firing broke out from the direction of Lieutenant Timothy’s “Rodney” group protecting the raiders from German reinforcements coming from inland.

Private Newman learned from the prisoner that he was a member of the Luftwaffe communications regiment and that there were 100 others in the immediate area. Most of these were billeted at Le Presbytére, where the firing was now coming from. These men were heavily armed and assigned to the defense of the Würzburg. They had mortars, but being mainly communications experts, they had rarely fired them. Further questioning revealed that the radar set had indeed been tracking the incoming raiders, and when it appeared that they were heading directly for the radar site the Germans had shut it down and departed.

While Private Newman and Major Frost were questioning the prisoner, Lieutenant Vernon was busy taking photographs of the radar itself. Flight Sergeant Cox made diagrams and sketches of the mechanics of the set. Soon incoming German fire forced the cessation of taking flash pictures of the set, since it attracted enemy gunfire. Cox went then to writing up a detailed report of the set, how it was set up, how the wheels were used, how the radar beam was adjusted, and a host of other technical details. The men then prepared to remove it.

The aerial proved an immediate problem. When no way to remove it seemed apparent, Lieutenant Vernon ordered it sawed off, which was quickly done. Although Cox and the engineers had brought along specialized tools, there were still parts of the radar that could not be removed properly. Instead, when such a problem was encountered, brute force was used to disassemble those parts, as carefully as possible. Cox later determined that they had had, “A stroke of luck. When the equipment was examined later it was found that the frame which we in that somewhat hasty moment regarded as no more than an encumbrance, something we had not the time to detach from the transmitter, contained the aerial switching unit that allowed both the transmitter and receiver to use the one aerial, a vital part of the design of any radar set.”

As the engineers struggled with dismantling the radar, enemy fire increased using the engineers’ flashlights as a target. One of the paratroopers was killed defending the chateau. But the radar was finally loaded onto the trolley, much to Major Frost’s relief. Now all that remained was to get away safely with the booty.

Firing was coming from every direction, and the situation was confused. Major Frost was particularly concerned that German flares were being fired from the beach, possibly meaning that Captain Ross and his men had failed to secure the escape route. Lieutenant Timothy had reported that things were under control on his front, but what about the rest? With the trolley loaded, Major Frost gave orders to withdraw. Lieutenant Naumoff was called in and told to lead the way to the beach.

On the beach Captain Ross and his small detachment had encountered Germans at a guard house. These had fired the flares that had worried Major Frost, and they had opened fire on the British with machine guns. Using rifles and Bren guns, the British replied but were pinned down. Lieutenant Naumoff and his group got down to the beach unobserved, but when the party pushing the trolley appeared on the cliff edge, the Germans on the beach fired at them with machine guns, seriously wounded Company Sergeant Major Strachan.

Captain Ross pulled him to safety and treated his many wounds. Then Major Frost received a message from Lieutenant Timothy that the Germans were pressing him and that they had recaptured the chateau. Major Frost gathered every man he could, including the engineers, signalers, and some of Lieutenant Timothy’s men and attacked the guard house. “Fortunately,” he later wrote, “the threat did not amount to much. The enemy was confused and did not know what he was up against. They hesitated and withdrew.”

Even as the attack materialized, a sudden shout behind the Germans gave notice that Lieutenant Charteris and his lost group had arrived! The Germans abandoned their machine gun and withdrew. Leaving Lieutenant Timothy to man the rear guard, Major Frost went down to the beach.

Lieutenant Charteris and his group had been dropped well south of their landing zone. Undaunted, they gathered their containers and began a difficult trek to reach Bruneval. At one point they marched through the town of Bruneval among several German soldiers who must have mistaken them for some of their own. One German made the mistake of joining the column, only to be silently killed before he could give a warning. Later they had to fight their way along, confusing both Major Frost who heard the firing and the Germans who did not know who was whom in the dark.

At the beach, the radio sets failed. A portable radio beacon was tried to no avail. Finally, green flares were fired. Lieutenant Timothy reported German vehicles approaching. Major Frost ordered his platoon commanders to prepare a last-ditch defense of the beach in case they were not evacuated. Offshore, the landing craft had been delayed by weather and the approach of German destroyers, which apparently never saw them in the darkness. They had approached the beach, ironically, after seeing the white flares fired by the Germans on the beach, and only then saw Captain Ross’s green flares.

As the boats approached, they opened fire on the paratroopers! Enraged, Major Frost and Captain Ross raced out into the water, shouting, cursing, and waving their arms for the fire to stop. When it did the raiders began to board the landing craft. The German radar was loaded aboard. Two men had been killed, and six others were missing. Two of the missing later contacted Major Frost aboard an MTB, but it was too late. They would have to evade through Spain or Switzerland.

Later German reports revealed just how fortunate Major Frost and his men had been. According to these, the German 685th Infantry Regiment was quartered in the area and several platoons of this unit were on exercises that night. Those platoons had been dispatched to attack the raiders as soon as they landed. It was some of these troops that pressed Lieutenant Timothy’s men. Their attack was credited by the Germans with capturing two raiders on the beach and another raider who was wounded in the fighting.

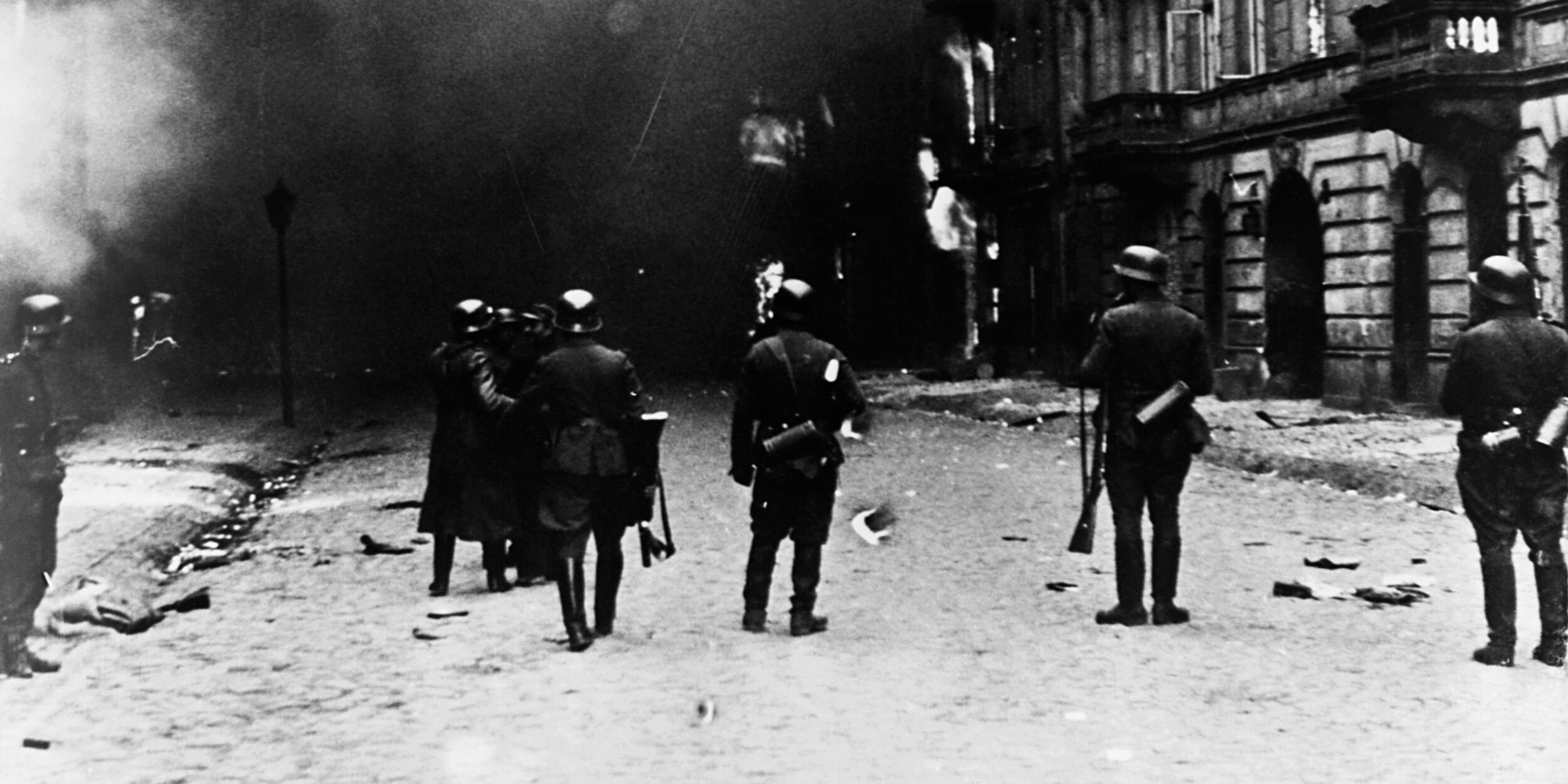

The German report concluded, “The operation of the British commandos was well planned and was executed with great daring. During the operation the British displayed exemplary discipline when under fire. Although attacked by German soldiers they concentrated entirely on their primary task. For a full thirty minutes one group did not fire a shot then suddenly at the sound of a whistle they went into action.” The report listed five killed, two wounded and five German military personnel missing. Four British troopers were captured.

Even before the party reached Britain, Mr. Priest had inspected the captured set and pronounced it in perfect condition. It was also found to be behind British radar development, much to the scientists’ relief. Company C, 2nd Parachute Battalion, went back to its training cycle. Major Frost would go on to lead the battalion at the battle of Arnhem, where they would win deserved fame at the “Bridge Too Far.” The mysterious Private Newman, most likely a German national that fled Nazi-Germany and a member of Number 10 (Interallied) Commando, disappeared. Flight Sergeant Cox returned to his family, and then to his earlier duties as a radar mechanic.The raid at Bruneval, one of the most successful British raids of the war, was soon overtaken by more spectacular events.

Nathan Prefer is the author of numerous books and articles on World War II. He received his Ph.D. in military history from the City University of New York and is a former Marine Corps reservist. Dr. Prefer is now retired and resides in Fort Myers, Florida.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments