By Kelly Bell

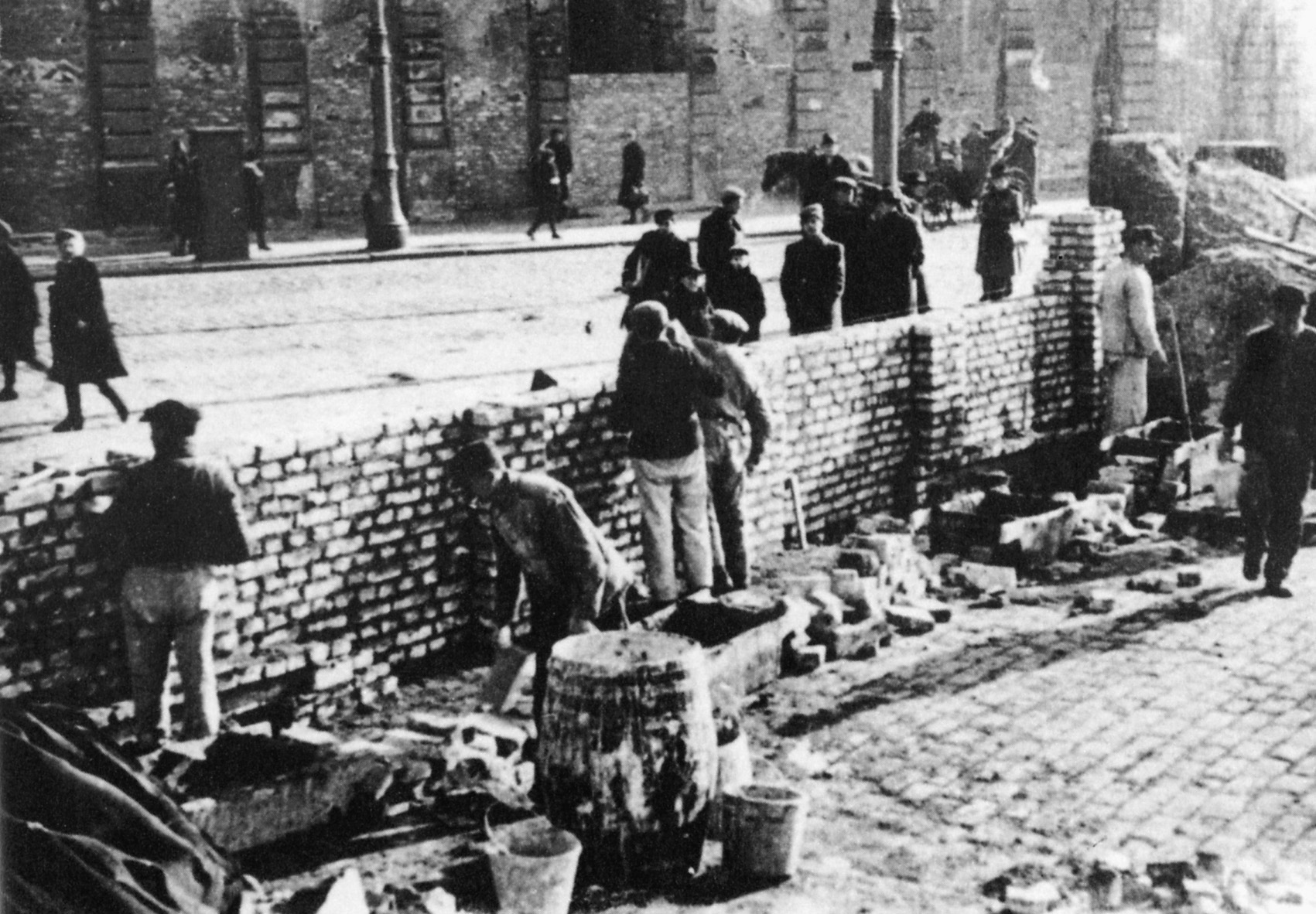

In April 1940, Adolf Hitler’s SS began building a walled compound in occupied Warsaw in which to imprison Jews who had survived the previous autumn’s bitter fighting as the German juggernaut romped through western Poland.

The Führer figured the best way to implement his longed-for extirpation of European Jewry was to first imprison the Jews in urban ghettos while vast extermination centers were constructed at Treblinka, Belsec, Sobibor, and Auschwitz.

Polish Jews were forced to pay German contractors to build massive, high walls around a hammerhead-shaped enclosure roughly 300 by 1,000 yards. Topped with barbed wire and studded with countless pieces of broken glass, this barrier encircled a pen into which 380,000 Jews from Warsaw and its environs were crammed at gunpoint.

By the autumn of 1940, this teeming slum was a netherworld of imponderable misery as the inmates were tortured and killed by starvation, cold, disease, and outright murder as patrolling Germans and their viciously anti-Semitic Ukrainian collaborators casually sniped at victims imprudent enough to raise their heads over the wall or show themselves at the entrances. These unfortunates generally were not trying to escape but to temporarily exit in attempts to procure food and medicine to smuggle back in to their families. The majority were children small enough to squeeze through the handful of miniature apertures or slip unnoticed through the gates.

By the spring of 1942, the Nazi guards had become such lethal marksmen that prisoners seldom ventured near the borders except at night. Some blood-lusting SS took to strolling ghetto streets and pumping bullets through baby carriages, doors, windows and the limp forms of those who had collapsed from starvation and illness. Two officers, Josef Blosche and Heinrich Klaustermeyer, became particularly adept at this pastime, and when they tired of shooting they were fond of creasing their faces into compassionate-looking masks and offering emaciated Jews flasks of coffee or milk laced with arsenic.

Simple barbarism was too slow for the Nazis, however. By this time they had finished the mass murder centers. On July 22, 1942, the SS and its lackeys began plastering posters on buildings throughout the slum to inform the Jews they were to be “resettled.” Within days, masses of people of all ages were packed into cattle cars and taken to the killing complexes. These round-the-clock deportations ended September 13, by which time 300,000 victims had been shipped to their deaths. Survivors decided there was no point in going down meekly.

Almost all of those still in the ghettos were bereave and therefore unencumbered and vengeful. A 24-year-old named Mordechai Anielwicz came to the forefront during the organization of the Zydowska Orgawizacja Bojowa (Jewish Fighting Organization, or ZOB.) Anielwicz had grown up quickly in one of Warsaw’s poorest neighborhoods. His scarred knuckles, fearlessness, and keen wits caught the attention of his comrades as they assembled and laid plans. His ideas on how to arm, train, and deploy the fighters-to-be were consistently sound and promising. He had been an urban warrior since he learned to walk, and before long the Jewish patriots came to regard him as their leader.

Armed defiance of the Nazis broke out as early as January 18, 1943, when a line of Jews waiting to be loaded onto a death train pulled revolvers and opened fire on their persecutors. This outbreak was swiftly pulverized, but it was a beginning. After four more days of frustrating cat-and-mouse clashes with the insurgents, the SS fled the ghetto.

Knowing the enemy would return in force, the Jews hastily enlarged existing cellars to accommodate their wounded and noncombatants. Anielwicz decided against his armed forces’ using bunkers, however. He feared such secure sequestering might make his troops feel too safe and thereby lessen their resolution to violently resist their tormentors. He also worked closely with a blond, blue-eyed Jew named Arie Wilner, who helped him obtain arms via the black market. Because he looked so “Aryan,” Wilner passed easily for a Gentile. Anielwicz and Wilner had hoped the Polish Underground (known as the “Home Army”) would supply the Jewish rebels with arms, but the Resistance generally was almost as anti-Semitic as the Nazis. Its initial assistance was inconsequential.

Likewise, the crooked merchants in the black market were often Nazi sympathizers, and soon after the January shootout the Gestapo was tipped off and arrested Wilner in his gun-filled apartment. Following prolonged, unsuccessful attempts to torture this hero into betraying his comrades, the SS decided to execute him, but because of a clerical error he was instead imprisoned in one of the city’s civil jails. The ZOB slipped into the lockup late one night, freed Wilner, and carried him to momentary safety. Although unable to walk due to the Gestapo’s having stripped the flesh from the bottoms of his feet, the youthful freedom fighter quickly resumed working for his people.

Despite his courageous determination, Wilner could no longer work outside the ghetto because the Germans now knew his face. Another blond haired Jew named Yitzak Zuckerman replaced him. Time was dwindling as Zuckerman worked feverishly to arm his people while the SS coiled to strike.

Scattered attacks on the Nazis and their sycophants mounted as springtime crept across the ghetto. Despite their miserable circumstances, many of the oppressed people were determined to celebrate Passover and prepared holy meals called Seders throughout the enclosure. The sacred day was April 19, but the Nazis had no intention of allowing the prisoners to worship in peace.

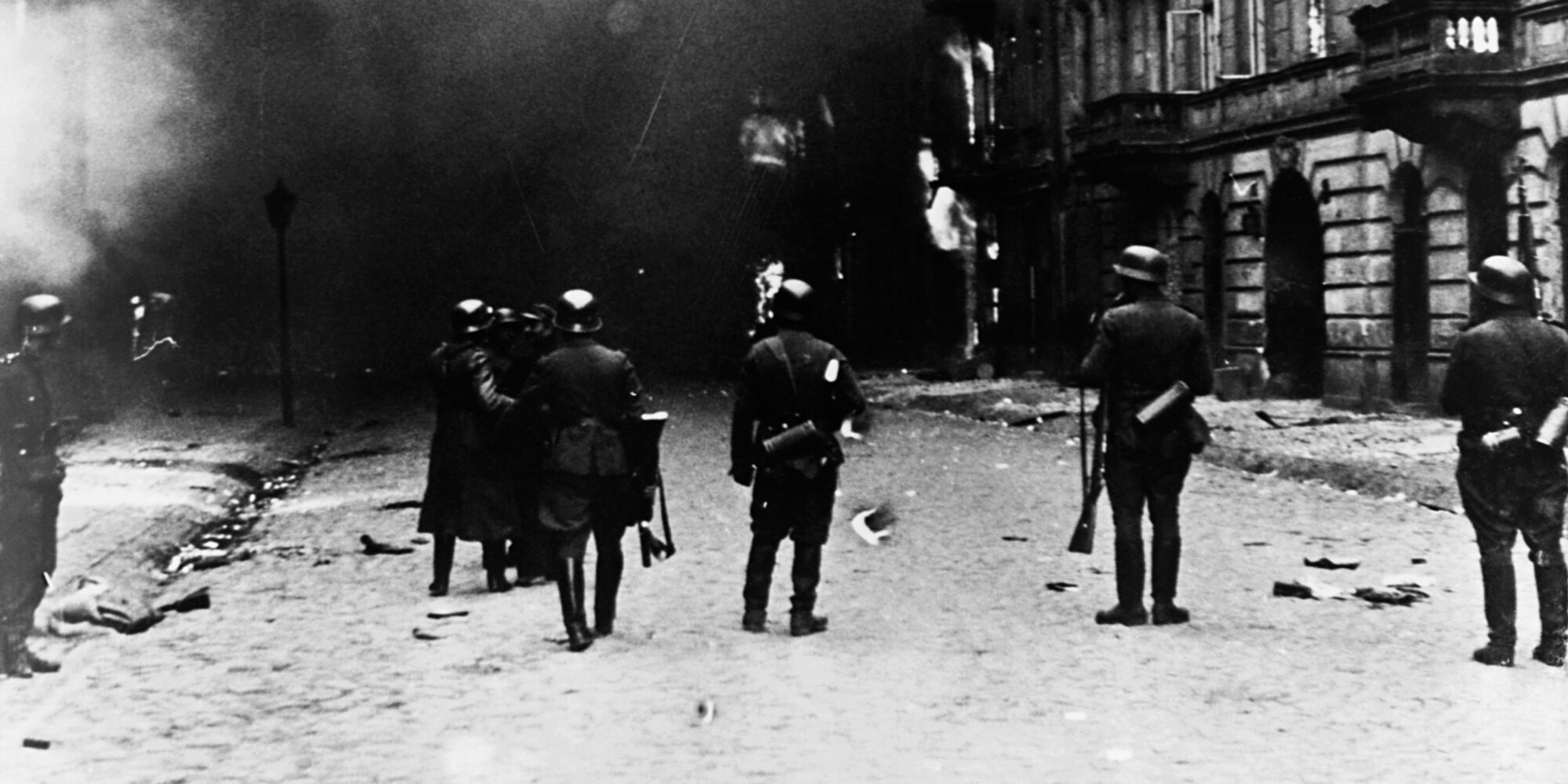

Early that morning, 850 Waffen SS from commanding Brigadeführer (Major General) Jurgen Stroop’s 28th Regiment, pushing a line of scared Jewish collaborators before them, entered the walled inner city and started down Zamenhoff Street, where the bulk of the surviving inmates were concentrated. A shower of grenades, Molotov cocktails, and gunfire quickly engulfed the invading column. Never having dreamed their quarry was so well armed, the attackers were decimated and scattered. Despite the best efforts of whip-swinging SS officers to lash their Ukrainian auxiliaries back into the battle, this first probe was hurled out of the ghetto in 30 minutes.

Unhappily for the fearless defenders, the enemy had 9,000 soldiers of the Third SS Infantry Division held in reserve in Warsaw, and at this point Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler personally ordered Stroop to take hands-on command of the campaign. As a child, Stroop had been mercilessly beaten by his parents. He grew into a hard, soulless soldier who had little patience with excuses from subordinates.

The units Stroop earmarked for assaulting the ghetto resisters were the SS Panzergrenadier Training and Reserve Battalion No. 3, the resident SS Cavalry Training and Reserve Division, the SS Police Regiment No. 22’s 1st and 3rd battalions, the Regular Army Light Antiaircraft Alarm Battery 3/8, a detail of engineers from the Reserve Rembertow Division, Reserve Engineer Battalion No. 14, 335 renegade Ukrainians calling themselves the 1st Trawniki Battalion, and 533 Warsaw city police officers and firemen.

On the evening of the 19th, Stroop tried to surprise the defenders by suddenly sending in a tank and two armored cars. The rebels used their Molotovs to immolate the tank and one of the armored cars and their crews. The surviving vehicle pounded a prudent retreat.

Stroop’s own uncompromising superior was leaning over his shoulder. As dispatches of the morning’s fighting reached Berlin, Himmler grabbed a telephone and rang up his man in Warsaw. The Reichsführer SS was fearful the fighting would spread throughout Poland, and with German forces in the East already hard pressed by the rebounding Red Army, a nationwide insurrection far to the rear would be a catastrophe. If this occurred, Himmler himself would have some serious explaining to do when his Führer asked for an update, and Adolf Hitler was the least understanding Nazi of all. Himmler pressured Stroop heavily, and with both men driven by fear results had to come.

Stroop devised a plan to send small units of well-armed SS to independently assault and destroy individual Jewish strongholds noted by the unfortunate first wave. Almost 2,000 men would move in with self-propelled armor and artillery. At first it seemed there would be a replay of the earlier rout as ZOB forces upended a squad that erected a protective wall of thick mattresses to hide behind as they fired on a rebel-occupied warehouse. Using their Molotovs, the Jews set the mattresses aflame then gunned down panicked Germans and Ukrainians as they bolted. However, the Nazis began using their own hand-thrown incendiary charges to ignite the buildings.

Still, the attackers were unable to take a single resistance fighter prisoner, though they did round up another 2,000 noncombatants and herd them to the rail yards for deportation. When the throng at the terminal became too large to manage, the SS began marching the captives into a large courtyard and shooting them. A number of Jews burrowed beneath the corpses on carts used to haul the dead away for burial. With the killers distracted by so many events inside the ghetto, they neglected the gates and many survivors were able to crawl from beneath the lifeless bodies of their loved ones and escape.

Stroop was trying to establish a powerful combat presence at the ghetto’s center so he could send his forces on search-and-destroy missions into surrounding areas. The ZOB was concentrated around the slum’s perimeter, and when the SS pierced this border they assumed the heaviest fighting was done. However, it was at this point that the Jewish Military Organization flew into the invaders.

Although numerically smaller than the ZOB, the JMO had begun preparing for this crusade earlier than its colleagues and was hence better-armed. Operating independently of the ZOB, these warriors seldom stayed long in one location. They would attack a Nazi element, inflict severe casualties, then expertly withdraw as soon as the enemy set up his defenses. Although Anielwicz could no longer call himself the overall rebel commander, he was nonetheless delighted by his brothers’ entry into the fight.

The JMO was headquartered in a large building in the central ghetto. Its fighters had strongly fortified this base, installing a pair of heavy machine guns on its roof. As the Germans and Ukrainians neared the big structure, the lofty gunners opened a lethal, plunging fire. The unsuspecting Nazis dropped in bunches as survivors opened up on street-level, long-abandoned shops where they incorrectly assumed the Jews were positioned. As the infantrymen emptied their weapons into deserted ruins, panzer crewmen panicked under this assault and retreated, leaving the dwindling foot soldiers bereft of armored support.

As the machine gunners savaged the enemy, their comrades hoisted a Polish national flag next to the rooftop gun nests. They next ran up the Star of David-emblazoned ensign that would soon become the banner of the recreated state of Israel. Along with being enraged and humiliated by this action, the Nazis realized the standards were high enough to be seen outside the wall and might incite Gentile Warsaw to riot.

As surviving SS men shuffled toward the gate through which they had entered that morning, they were being watched. Singing an anti-Semitic lampoon in a forlorn effort to lift their spirits, they got yet another shock when they were again showered with Molotovs and grenades. Those not roasted or blown to bits scrambled through the egress. In the gathering darkness behind them, a cast whose fighting prowess and spirit would have impressed King David began to emerge from hiding and take stock of its situation. They had accomplished much, but still had little to lose.

April 20, 1943, the second day of the uprising, was Hitler’s 54th birthday. With an anxious Himmler awaiting results, Stroop divided fresh troops into a dozen 36-man units to be dispersed in an effort to force the Jews to fight in multiple locations simultaneously and dilute their strength. The savvy irregulars, however, correctly perceived this strategy when they noted the mass of troops pouring through the main gate that morning and attacked before the Nazis had time to deploy.

The Germans and their vassals had expected to shoot first, so this quick thinking by the insurgents meant the invaders were again taken aback. In minutes, a third of this latest wave of intruders was dead or wounded. The Nazis carried their injured to the center of the ghetto, assuming they would be out of range of the defenders. The rebels followed through attic passageways and shot down 11 more of the enemy.

Elsewhere, an SS company, bent on removing the taunting flags, made straight for the JMO nerve center. Running a gauntlet of small arms fire, they left their dead and wounded where they fell as they stampeded for the building. As they drew near, one of their Molotov-splattered tanks exploded, and the twin machine guns reopened their killing volleys. Although the besiegers used a flamethrower to temporarily set the rooftop afire, the heavy guns remained undamaged and beat back the attack.

Nevertheless, the invaders seemed to be achieving moderate territorial gains as the day continued, but the Jewish withdrawals being noticed by the Germans and Ukrainians were a masterfully staged ruse. As they followed the retreating Jews, they were approaching a lethal ambush. As hundreds of SS poured into a courtyard along their quarry’s path of flight, the pavement beneath them erupted as a sapper ignited a bushel of dynamite secreted beneath the cobblestones. The blast killed over 100 men and shattered the Nazis’ budding confidence.

Another German column, churning down a street in the ghetto’s brush-making district, was virtually annihilated when it drove into a hastily arranged ZOB ambush. When Stroop learned of this latest outrage, he sent an entire regiment into the sector. Using portable artillery, heavy machine guns, and flamethrowers, the SS hosed the buildings with tons of lead, steel, and oily tongues of flame in fruitless efforts to flush out the unseen gunmen. They finally drew fire from a rooftop, but it was only a tiny rear guard the partisans sacrificed as the bulk of the resistance fighters slipped away. By nightfall, the Jews remained firmly in control of their ghetto.

By this time Stroop was close to panic. He had lied to Himmler, telling him just nine soldiers had died in the fighting instead of the 300-plus who had actually fallen. It was only a matter of time before Berlin learned the truth, and for his own sake he had to crush the rebellion first. Stroop concluded that the sole remaining means by which he could accomplish this was to employ his artillery, which had been held back for fear of destroying the ghetto’s Gentile-owned armaments facilities. The factories would be pulverized regardless of their value to the Reich.

Distraught executives rushed to their plants and bellowed for remaining workers to surrender while the buildings still stood. As slow-moving trucks lumbered along picking up dispirited Jews emerging from the factories, German infantrymen accompanying the vehicles were decimated by snipers. Shortly afterward, rebels hurling the now-dreaded grenade and Molotov cascade bushwhacked an SS convoy ferrying troops out of the central ghetto. Tumbling from the blazing transports, the Nazis were cut down by sharpshooters.

At this point, as the defenders were busy with targets in the streets, some of Stroop’s other men began furtively positioning barrels of gasoline in front of the buildings, out of sight of the preoccupied partisans directly above them. After affixing detonators to the drums, the sappers primed the charges and scurried to a safe distance.

The roiling fireballs had exactly the result Stroop had hoped. The area quickly became a swirling inferno. As tons of charred debris fell on them, the subterranean bunkers where the Jewish noncombatants sheltered began to collapse. Some fighters on upper floors were trapped by flames and hurled themselves to their deaths through windows. Others who tried to surrender to the humiliated SS were gunned down in cold blood. Some ZOB soldiers charged straight through groups of startled Germans and managed to escape, for the moment.

Anielwicz realized that his decision to not excavate underground hideouts for his troops had been a colossal error. Now his men and women had nowhere to take cover except in structures that would soon be cinders. Their sole prayer was that the terrified civilians in the remaining intact bunkers would be able to make room for them, but when they tried to gain entry to these hideouts they received a shocking reception. The women, children, elderly, cripples, and cowards huddled in these holes refused to open the concealed doors to armed rebels for fear they were unhealthy company.

The unarmed people in hiding knew the SS would continue combing the smoldering ruins as long as armed resistance persisted. If the fighting died out, the enemy might be convinced that every Jewish life had been snuffed out, overlook the survivors, and leave the ghetto. The noncombatants were anxious for the revolt to end and considered the partisans persona non grata.

As Anielwicz tried to resolve this awkward development, the JMO was becoming similarly hard pressed. Continued attacks on its headquarters had killed a number of its members, and shellfire had knocked out one of the precious rooftop machine guns. JMO commanders realized their men were exhausted and weak from hunger, but still game to fight. Removing the remaining gun from the roof, they left the flags as bait to lure the Germans into attacking.

The remaining rebels hid on the ground floor and waited for the enemy to charge the building while still expecting its garrison to be aloft. For a quarter of an hour, the SS held back, suspicious of the suddenly silent structure. Then, an Aryan-looking Jew in a stolen SS uniform strolled out the front door and approached the Nazis. After convincing them he was a fearless German who had earlier entered the building alone to scout it, the youthful resistance fighter lured the murderers inside after telling them the JMO had fled.

As a platoon of the enemy followed their bogus guide to a staircase, the hidden Jews opened fire, killing a dozen SS and hounding the survivors from the post. Stroop handpicked a second unit to assail the stronghold, but the highly decorated lieutenant who led the charge, Otto Dehmke, was killed at the beginning of the attack when he held on to a grenade too long. Unnerved and leaderless, his men ran.

Resuming his scorched-earth tactics, Stroop had his men torch the neighborhood around the JMO headquarters. Soon the afternoon was punctuated by the screams of women and children trapped by the conflagration. Many jumped from upper floors rather than burn. Others threw down mattresses first in hopes of softening their landings. Those who did survive the fall were immediately murdered. Many shot themselves or gulped poison, while others tried too hard to find exits and were surrounded by flames. At last, Maj. Gen. Stroop was fulfilling his assignment. The ghetto Jews were dying—horribly.

Using sound-detecting equipment and dogs, the Nazis hunted remaining insurgents like they were wild animals. The few who were still walking were taken for deportation, while those too badly burned or otherwise injured were shot or beaten to death with rifle butts. Elderly Jewish men were forced to dance before being murdered: young women were beaten and raped.

Anielwicz and his surviving men used the enemy’s preoccupation with committing atrocities to duck unnoticed into a cavernous bunker excavated by thieves and smugglers before the war. After settling into the well-equipped robbers’ den, Anielwicz sent word to Zuckerman, pleading for more weapons and ammunition. Despairing of receiving substantial support from local Gentiles, Zuckerman began circulating a flyer throughout Warsaw and its environs. It urged all locals to actively aid the revolt and truthfully assured them they were not safe from Nazi avarice. This call to arms fell into Stroop’s hands just after he received a cable from Himmler castigating him for not having already crushed the rebellion.

The terrified general issued draconian decrees forbidding area Gentiles from so much as entering the ghetto or assisting Jews by any means. He then had an entire Christian family shot for hiding a Jewish child. He called on the Luftwaffe to bomb sections of the ghetto suspected of still containing insurgents, but the Home Army finally began attacking SS patrols in the ghetto. Non-Jewish civilians also started donating whatever they could to assist the valiant resistance.

As bombers hammered unburned sectors of the slum, fear-crazed crowds emerged and begged ZOB members to save them, but the hysterical Nazi attacks had succeeded in disrupting the rebels’ command and communication. Anielwicz could not contact and coordinate the units still topside. Now that resistance had decreased, Stroop decided it was safe enough to have his men continue their depredations through the night.

The general intended to burn all but a narrow strip of territory in the central ghetto, forcing survivors into this slender corridor. By April 24, up to 2,500 people had been captured via this tactic, and the rail depot was again swamped. So, Stroop’s first order of the day on that Easter morning was for his men to force captives into the courtyard of Pawiak Prison and shoot them in small groups. He also decided the collaborationist Jewish police force had outlived its usefulness. Many of these traitors had become wealthy by taking bribes from those who had no choice but to trust in the turncoats’ empty promises of safe passage out of the city. After taking all these desperate people had to offer, they would turn them over to the SS. Expecting to use their blood money to live comfortably in postwar Europe, these men were jarred back to merciless reality when they too were knocked facedown in the penitentiary’s plaza and shot in the back.

Later that day, a couple of JMO operatives dressed in SS garb sauntered into a German supply depot and opened fire on the station’s personnel. A great deal of confusion developed because Nazis running to the fray could not tell foe from friend. As the Germans blazed away at each other, the disguised Jews and a few of their comrades who had surreptitiously followed grabbed as many gun and ammunition crates as they could carry and bolted back to the ghetto.

Weapons shipments were also arriving from the Home Army, but partisan manpower was so depleted that further resistance could be little more than a show of defiance. At month’s end, Anielwicz had a letter smuggled from his bunker for delivery to the Polish government-in-exile in London. It outlined the ongoing genocide and sundry Nazi barbarism and called on the Western powers to do everything in their ability to cripple Germany before European Jewry ran out of time. The missive did not reach England until a full month after the end of the ghetto uprising.

The captured armaments never reached Anielwicz, so when he and those with him decided to go out in a blaze of glory on May 1, they did so with hopelessly inadequate weaponry. Watching as a Jewish traitor led a squad of SS to a burned-out structure where a few Jews still huddled, remaining rebels were nonplussed when, seconds after the collaborator pointed out his peoples’ hiding place, a German officer drew his sidearm and shot this guide.

Poking their muzzles through the windows of an adjacent building, the partisans uncorked a volley at the astounded Nazis. Three immediately fell, and the others took to their heels. The guerrillas moved to another position, and when the reinforced killers returned less than an hour later they were again taken unawares and went scurrying like hares, abandoning their dead and wounded.

This incident renewed Stroop’s dread. He hurried to the ghetto’s main gate to personally oversee the rounding up of one of the last groups taken for deportation. Suddenly, a young rebel jerked out a revolver and pumped three fatal rounds into an SS officer. Stroop joined in the instant fusillade that tore into the unbowed hero. The Brigadeführer walked over to the dying Jew and looked into his fearless eyes. The boy raised his head and spat on the general, then sank back to the pavement.

That afternoon, the SS tortured a child into revealing the bunker’s entrance. Over the next two days, the killers used bullets, bombs, and gas to slay most of its final occupants. The fighting had simmered down to sniping from a few diehard holdouts and to the escapes of a few survivors, most of whom were shot as they emerged from sewers through which they had fled. By this time, the Home Army was ardently assisting, but its units were repeatedly betrayed by canine patrols.

On May 5, Stroop’s top aides informed him that approximately 45,000 Jews had been killed or caught during the rebellion. Unknown to the Germans, Anielwicz had survived the assault on his bunker and was still alive in its reeking depths. On the 9th, the murderers returned and, to play it safe, pumped the cellar full of gas and wiped out the few pathetic survivors. They then dynamited the bunker.

Over the next few days, tiny knots of Jews trickled out of the ghetto and into the forests bordering Warsaw in hopes of joining the Home Army, although Stroop recorded stout armed resistance as late as May 10. An uneasy quiet descended onto the charred, smoking ruins, but it was shattered on the 16th when Stroop had the huge 66-year-old Warsaw synagogue blown to bits. That evening, he sent a cable to Himmler: “The former Jewish quarter of Warsaw no longer exists.”

Jurgen Stroop was awarded the Iron Cross First Class for his actions against the Warsaw Jews and was promoted to command all SS forces in Greece. After the war, he was returned to Warsaw and tried for his crimes against humanity. He was hanged March 16, 1952.

Kelly Bell is a full-time freelance writer who specializes in historical subjects. He resides in Tyler, Texas.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments