By Chuck Lyons

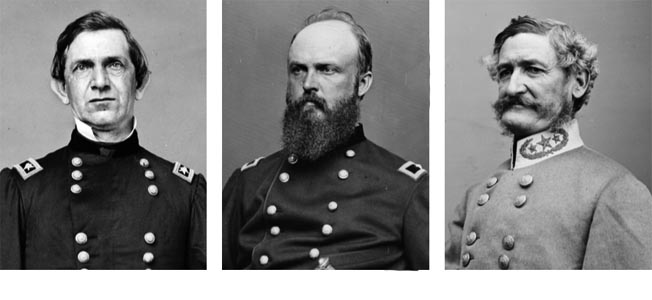

In June 1861, two months after Confederate artillery fired on Fort Sumter to begin the Civil War, 44-year-old, Louisiana-born Henry H. Sibley arrived in Richmond, capital of the newly formed Confederate States of America. A career soldier, Sibley had come to offer his services—and a plan. An 1838 West Point graduate, Sibley had served in the Seminole War and had been stationed for many years in the West. He was with the 1st Dragoons in Taos, New Mexico, when the war broke out and quickly resigned his commission to join the southern cause.

The curly-haired Sibley was known in military circles as a competent soldier and a heavy drinker. In Richmond, he explained to Confederate President Jefferson Davis that he wanted to raise a force in Texas, start north from El Paso, and capture Union forts along the Rio Grande until he reached Santa Fe. His men could live off the land, Sibley said, and would be greeted as heroes wherever they went by secessionists in the territory. After taking Santa Fe and consolidating his forces, Sibley intended to march on Colorado and California.

The Confederacy Looks West

Sibley’s plan meshed well with ideas Davis himself had long espoused. The Confederate president believed strongly in western expansion, and he viewed the vast territory of New Mexico, which stretched from Texas to California, as particularly ripe for the expansion of slavery. As secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce, Davis had been instrumental in the 1853 Gadsden Purchase, which had brought the Southwest into the Union, and before leaving the War Department in 1857 to return to the Senate, Davis had gone so far as to import 74 camels from North Africa and the Middle East to test their usefulness in the newly acquired desert countryside. (The military considered the experiment successful, but the Civil War put an end to the exotic project.)

Sibley’s plan, if successful, would give the Confederacy access to the fabulous gold and silver fields of California, Colorado, and Nevada as well as access to the Pacific Coast ports of California, which were not being blockaded by the Union Navy. Davis agreed that there were wide pro-Confederate feelings in most of the western territories. He gave Sibley a commission as a Confederate brigadier general, with command of the newly created Department of New Mexico. For the time being, that was all Davis could give him; the Confederacy had no supplies or equipment to spare. Sibley was on his own, armed only with vague orders to drive all Federal troops from his department.

Sibley’s first problem was supply. Texas had seceded from the Union on February 1, 1861. At that time, the Federal arsenal in San Antonio and the whole Department of Texas was commanded by Brevet Maj. Gen. David E. Twiggs, 71, one of the four highest-ranking officers in the U. S. Army. When Texas seceded, Twiggs, a native Georgian with pro-slavery sympathies, began negotiations with the Texans over the arsenal and the matériel it contained. Twiggs repeatedly asked Washington for instructions and received ambiguous replies. He told fellow officers he would never fire on American citizens under any circumstances but that he would surrender the U.S. property in his department to the state of Texas “whenever it was demanded.”

Recruitment in El Paso

Finally, Twiggs wrote to Washington revealing his Confederate leanings and asking that he be relieved of command—he was the most senior officer in the Army to declare for the South. Orders were issued granting Twiggs’s request and assigning his command to Colonel Carlos A. White of the 1st New York Infantry. Before these orders could be put into effect, however, a sizable force of Texans moved into San Antonio on February 16 and seized control of the arsenal and other Federal installations. Twiggs quickly surrendered his command and turned over all Federal property, supplies, and buildings—including 19 forts—to the State of Texas.

At about the same time, Confederate Lt. Col. John R. Baylor raised a 350-man regiment called the Texas Mounted Rifles, marched to El Paso, and accepted the surrender of the Union’s Fort Bliss and the supplies it contained. Baylor then moved north along the Rio Grande to the village of Mesilla. Dressed in a blue jacket, red sash, and a silver belt buckle embossed with the Lone Star of Texas, Baylor cut a distinctly piratical figure. He went on to capture Fort Fillmore, which had been abandoned after its supplies were burned. On August 1, Baylor formally declared the Confederate Territory of Arizona, installing himself as military governor and Mesilla as the capital. He then sent Granville H. Oury as Arizona’s delegate to the Confederate Congress.

Sibley made his way to San Antonio, where he recruited another 800 men. By fall that number had grown to 1,100. Meanwhile, Baylor and his forces marched to El Paso, arriving in mid-December to find things already in motion for the Confederacy. Besides Baylor’s gains, the Union garrison at Fort Thorn, 50 miles north of Fort Fillmore, had retreated to Fort Craig, and the garrison of Fort Stanton, east of the river, had fled to Albuquerque. Three days after New Year’s Day, 1862, Sibley moved against Fort Craig, which was commanded by Colonel Edward R.S. Canby and defended by a force of 3,800 men, about one-third of whom were in the Regular Army. The remainder were militia and volunteers in various stages of training and discipline.

Canby, who had taken command of the Department of New Mexico when its former commander, Colonel William Loring, resigned his commission and switched to the Confederacy, was born in Kentucky and raised in Indiana. He had served in the Mexican War, during which he had twice been cited for gallantry, and in the Florida Indian wars. The two opposing commanders knew each other well. Canby had been at West Point with Sibley, had been best man at Sibley’s wedding, and was married to a cousin of Sibley’s wife. The two men had also campaigned together against the Navajo Indians in the northern part of the territory. A careful officer, Canby talked little but acted efficiently in the face of emergency.

In mid-February, Sibley’s force, with the addition of Baylor’s men, headed north in sleet and snow to the vicinity of Fort Craig. On hand were Sibley’s three regiments, the 4th, 5th, and 7th Texas Mounted Volunteers under Colonels James Reily, Tom Green, and William Steele, respectively. The 4th and 5th were each supported by two batteries of four 12-pounder mountain howitzers seized earlier from the San Antonio arsenal. Two companies of Green’s 5th Regiment had been converted into lancers whose nine-foot-long spears were topped with colorful streamers and foot-long razor-sharp steel blades.

A Motley Force of Gamblers & Gunmen

In addition, there were six companies from Baylor’s army led by Major Charles L. Pyron and a newly formed company of volunteers—mostly gamblers, gunmen, and other unsavory characters—who had been collected in and around Mesilla. In all, about 2,500 Confederate troops headed out, trailing 15 pieces of artillery, including a battery of 6-pounders inherited from Baylor, a supply train, and a herd of cattle. A number of sick and dying men were left behind, along with a detachment of 630 men under Steele, who was charged with protecting the Mesilla-El Paso region. It was a decidedly motley force, armed mainly with squirrel guns, double-barreled shotguns, and Bowie knives and dressed in civilian clothes, Confederate gray, and even Union blue seized at the time of Twiggs’s surrender.

Fort Craig was manned by 3,810 Federal troops including elements of the 5th, 7th, and 10th United States Infantry and companies of the 1st and 3rd Cavalry. The rest of the men were local volunteers, including 10 companies of the 1st New Mexico Regiment commanded by legendary frontiersman Christopher “Kit” Carson. The defenders had a battery of two guns at their disposal.

After a couple of days of maneuvering and slight skirmishes, Sibley crossed the river to the east side on February 19 and moved north in an attempt to circle the fort. Confederate reconnaissance had concluded that the fort could not be taken by direct assault without the support of heavy artillery. Sibley decided, at Green’s suggestion, to initiate a circling maneuver to force Canby out of the fort and onto ground of Sibley’s choosing.

A Feint Toward the Fort & Explosive Mishaps

Canby could not let Sibley block the road north to Albuquerque, and he sent infantry, cavalry, and artillery across the river on the 20th to check the Confederate advance. They found Sibley waiting on a high mesa at Valverde, and his massed cannon and rifle fire quickly broke the Union attack. During the night, Union Captain James “Paddy” Graydon, who had served as enlisted man in the dragoons before becoming a hotelier and saloonkeeper and who now commanded an independent scouting company of New Mexicans, had what to him at the time seemed to be an inspiration. He loaded wooden boxes of 24-pound howitzer shells onto two mules and led a small force toward the Confederate camp. When they neared the enemy camp, the men lit the howitzer fuses, slapped the mules, and ran for cover—only to find that the mules had also turned and were loyally following them. The men again tried unsuccessfully to steer the mules into the Confederate camp, finally gave up, and ran for their lives. They were able to get just far enough away to escape injury when the shells—and the mules—exploded. No Confederates were killed in the highly irregular attack, but a number of their own mules stampeded into the darkness and were lost.

That morning, Sibley sent the 5th and 7th Regiments to make a feint toward the fort while the 4th and a battalion of Baylor’s troops moved upriver to seize the ford at Valverde. Canby dispatched 220 regulars of the 1st and 3rd Cavalry and four companies of mounted volunteers to stop them. The Union men suffered scattered casualties crossing the river but were able to force Sibley back to the far side of the mesa. From there, Sibley’s men tried mounted charges against Canby’s flanks and dismounted charges against the center of his line, but all the attacks were repulsed. About 10 am, Canby sent 720 regulars, a company of Colorado volunteers, and eight companies of Kit Carson’s 1st New Mexico troops to join the fighting.

At noon the feint toward the fort was discontinued, and Green with his 5th Regiment joined the fight at Valverde. Shortly after that, Sibley—feeling ill, possibly from too much whiskey—retired from the field, leaving Green in charge. Canby, freed from his duties defending Fort Craig, raced north to take command, bringing with him all his remaining troops except for a small detachment left behind to guard the fort.

About this same time, the Confederates launched a cavalry charge against the Union right that included 40 lancers from the 5th Texas, the only recorded instance of lancers being used in the Civil War. The lancers and cavalry encountered a devastating fire that finally broke the charge. In columns of four, banners fluttering and spears leveled, the lancers rode forth against the Coloradans. “Some of them came near enough,” one of the Colorado volunteers wrote, “to be transfixed and lifted from their saddles by bayonets, but the greater part bit the dust before their lances could come in use.” Union Captain Theodore H. Dodd shouted: “They are Texans, give them hell!” His men, who had no love for Texas residents, responded with withering fire. Only three of the 40 lancers got off the field unharmed.

Green Charges the Union Batteries

In the afternoon, Green massed his cavalry with dismounted men behind and charged the Union batteries at both ends of Canby’s line. The attack to Canby’s right under Major Henry W. Raguet was easily repulsed, but on Canby’s left the screaming Texans under Major Samuel A. Lockridge broke through the defensive line and seized several of the guns in Captain Alexander McRae’s artillery battery. Hand-to-hand fighting ensued, during which Lockridge and McRae were shot dead, possibly by each other. Canby sent in two reserve companies and tried to recover the guns, but the reserves were beaten back. Green prepared a counterattack to sweep the badly shaken Union forces from the field, but Canby judiciously sent a flag of truce and requested an armistice to care for the wounded and bury the dead. Remarkably, Green granted the request. Meanwhile, against accepted protocol, Canby withdrew across the Rio Grande to Fort Craig.

Federal casualties at the Battle of Valverde were 68 men killed, 160 wounded, and 35 missing or taken prisoner. Five of the Union’s eight field pieces were also captured. Confederate casualties were 36 dead, 150 wounded, and one missing. It was a clear-cut Confederate victory, but the Texans had also lost numerous wagons and precious supplies. Many of the cavalrymen in the 4th Regiment had to convert to the infantry for lack of fresh mounts.

The next morning, Sibley demanded the surrender of the fort, but was rebuffed by his old friend Canby. After giving his men a day’s rest, Sibley headed north, intending to live off the land until he reached Albuquerque and seized the Federal supplies stockpiled there. When he approached Albuquerque, however, he found to his chagrin that the garrison had burned all the supplies in the city before falling back to Santa Fe. Sibley moved into the city unopposed, but some $6 million worth of matériel had literally gone up in smoke. Four days later, on March 5, a detachment of 600 Confederates moved with equal ease into Santa Fe, the territorial capital. Once again, Federal troops had burned any supplies they could not take with them, and the territorial government had relocated to Las Vegas, near Fort Union.

Tight Supplies in a Hostile Region

Sibley and his men soon felt the pinch of tight supplies and the indifference or outright hostility of New Mexico residents in the areas they had captured. Still, Fort Craig was an island of blue surrounded by southerners and cut off from any immediate aid. All that stood between Sibley and his triumphant march to California were the troops at Fort Union, 60 miles east of Santa Fe. Fort Union had become the gathering point for all the Union troops flushed out during Sibley’s northern ride up the river, but Sibley, who had been stationed at Fort Union before the war, felt that he knew the fort’s weaknesses and would have an easy victory once he reached it.

Unknown to Sibley, Federal supporters had begun making moves to reinforce Fort Union. Colorado’s acting governor, Lewis L. Weld, ordered seven companies of the Union’s 1st Colorado Volunteer Infantry Regiment stationed at Denver and three companies from the Indian country southeast of the city to march through heavy snow and relieve the fort. Thrashing through waist-deep snowdrifts, the troops covered the last 92 miles in 36 hours, a grueling pace that caused many horses and mules to drop dead in harness. The reinforcements, led by Colonel John P. Slough, arrived at Fort Union on March 11. One of the Colorado companies was mounted; the remainder of the 950 men had walked over 400 miles in 13 days.

On March 22, Slough left the fort, heading west with 1,342 men and two four-gun batteries. They moved along the Old Santa Fe Trail, leaving only a small detachment behind at the fort. Canby, unaware of Slough’s arrival, had ordered Colonel Gabriel R. Paul to hold the fort until Canby joined him and to not engage in any major battles. Slough either did not receive, or else ignored, the order. Meanwhile, a Confederate force comprised of six companies of Baylor’s troops, four companies of the 5th Regiment, three locally recruited scout companies, and a battery of two 6-pounders headed east under the command of Major Charles L. Pyron.

“Gone Off to Hell With a Crazy Preacher Who Thinks He Is Napoleon Bonaparte”

Slough’s force camped at the town of Loma. The next morning, Slough sent Major John M. Chivington ahead with 418 men to make a quick raid on Santa Fe. Chivington, a fire-and-brimstone Methodist preacher and a fearsome and experienced Indian fighter, originally had turned down a commission as a chaplain to take what he called a “fighting commission.” Brash and irreverent, the six-foot-four, 260-pound Chivington had clashed repeatedly with Slough on the way from Colorado. In a letter to superiors, Slough wrote that half the regiment had “gone off to hell with a crazy preacher who thinks he is Napoleon Bonaparte.”

Crazy or not, Chivington never made it to Santa Fe. On the morning of March 26, he and his men entered Glorieta Pass, a rocky defile through which the Old Santa Fe Trail twisted around the southern edge of the Sangre de Christo Mountains. By afternoon they were approaching the western end of the pass when they entered a narrow valley called Apache Canyon and ran headlong into the startled vanguard of Pyron’s column.

Crazy or not, Chivington never made it to Santa Fe. On the morning of March 26, he and his men entered Glorieta Pass, a rocky defile through which the Old Santa Fe Trail twisted around the southern edge of the Sangre de Christo Mountains. By afternoon they were approaching the western end of the pass when they entered a narrow valley called Apache Canyon and ran headlong into the startled vanguard of Pyron’s column.

The Union men took cover in pine trees on the left, where Chivington quickly regained control of his troops and sent them scurrying up the steep sides of the canyon. Their firing forced the Confederates to retreat into a deep, narrow gorge, where they destroyed a log bridge over a dry streambed and set up their artillery. Firing from whatever cover they could find, the Union troops gradually pushed the Confederates back. “We’ve got them corralled this time!” shouted one Colorado volunteer. “Hurrah for the Pikes Peakers!”

Chivington rode among the men “with a pistol in each hand and one or two under his arms … a conspicuous mark for Texas sharpshooters,” Private Ovando J. Hollister of the Colorado volunteers later wrote. Looking like “a mad bull” in the words of another onlooker, the preacher-turned-soldier ordered a mounted Colorado company to charge. With pistols firing and swords gleaming in the sun, Captain Samuel Cook and his men charged up the valley, leaped the streambed, and engaged the enemy in hand-to-hand combat. “On they came to what I supposed certain destruction, but nothing like lead or iron seemed to stop them,” one Texan wrote.

Retreat Down the Valley

The Confederates were able to save their artillery and continued to fight as they retreated down the valley. Finally, with darkness coming, Pyron abandoned the fight. Chivington paused to gather up his dead and wounded, and a truce was called to tend to casualties. Confederate losses from the engagement were four dead, 20 wounded, and 75 captured. Chivington reported five of his men killed, 14 wounded, and three missing.

Pyron desperately called for reinforcements, and the 4th Texas Regiment and a battalion of the 7th under Lt. Col. William R. Scurry rode through the night, reaching Pyron’s camp at Johnson’s Ranch about 3 am. Scurry, as ranking officer, took over command of the entire force, which had now grown to about 1,000 men. When a Federal attack did not take place the following morning, Scurry waited another day and headed back into the canyon on the 28th, leaving his supply wagons back at Johnson’s Ranch. Meanwhile, Chivington had fallen back to Apache Canyon and joined Slough’s main column.

Alerted that the Confederates were moving against them, Slough divided his command into two parts, each smaller than Scurry’s force. Leaving behind one force to guard his supplies, Slough began moving up the canyon with about 850 men. Chivington, meanwhile, guided by Lt. Col. Manuel Chaves and a group of New Mexico volunteers, took 490 Coloradans and began climbing the mountains in an attempt to get behind enemy lines.

Glorieta Pass: “A Terrible Place for an Engagement”

About 11 am, Slough’s and Scurry’s men met at Glorieta Pass, which one Union lieutenant described as “a terrible place for an engagement.” The pass was a narrow gorge with steep walls on each side. There was no room for maneuver, and the men grabbed what sparse cover they could. Slough formed a battle line by placing two batteries of guns, each supported by a company of infantry, across the road and partly up the northern slope. Scurry also formed a line. Fighting became intense as the outnumbered Union troops tried to advance. Confederate pressure flanked the Union left, and Slough pulled back 800 yards to form a new line, while Union artillery was able to knock out two of Scurry’s guns and Union rifle fire kept Confederates from manning the remaining gun. “The Texas battery soon slackened its fire until it almost ceased,” Hollister wrote.

The Texans charged but were repulsed with more hand-to-hand fighting on the right and in the center. The charge on the left, however, was able to flank the Union line and force Slough to fall back to a new position east of Pigeon’s Ranch, where Slough’s troops had first sighted the Confederates that morning. In the bloody conflict, Raguet was mortally wounded and Pyron had a horse shot out from under him. After six hours of heavy fighting, with both armies on the edge of exhaustion, Scurry suggested a truce, which was called about 5 pm.

Meanwhile, Chivington and his men had crossed 16 miles of treed country to a 200-foot bluff overlooking Johnson’s Ranch. They descended the bluff with ropes and leather straps, surprised the guards left behind with the supply train, and captured the wagons. Then they burned 85 wagons and provisions and bayoneted the 500 horses and mules that had pulled them.

With the catastrophic loss of his supplies, Scurry had no choice but to call off the engagement and try to get his men back to Santa Fe and Albuquerque. Under cover of the truce, the Confederate troops left their wounded at Pigeon Ranch and slipped away from the field. Rather than chase and possibly finish off the Confederates, Canby recalled his troops to Fort Union, fearing an immediate attack on that facility. Slough obeyed the order grudgingly, then resigned his commission in disgust. Scurry reported losses of 36 killed, 60 wounded, and 25 captured at the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Union losses totaled roughly the same although Slough insisted that the Rebels had lost at least 275 men.

Sibley Reluctantly Returns to Texas

Four days later, on April 1, Canby, who had just been promoted to brigadier general, headed out from Fort Union with 1,210 regulars and volunteers. The two armies exchanged artillery salvos outside Albuquerque to little effect, then settled down to await further developments. Sibley was basically without supplies and had little prospect of living off the land. He had learned the hard way that he could expect little help from the indifferent or hostile locals.

He had no choice but to return to Texas. On April 12, Sibley began his retreat, burying eight brass howitzers near the Albuquerque town plaza and moving south along the Rio Grande. Canby pursued with reinforcements from Fort Union, and the two armies clashed briefly near the town of Peralta. When the engagement petered out, the Confederate forces continued to move south along the west side of the river, while Canby’s forces shadowed them on the east bank. On the third morning, the Federal troops awoke to see the Confederate camp abandoned, its fires still burning. Sibley and his men had slipped away in the night, swinging west from the river around the base of the Sierra Magdalena Mountains on what would become a torturous 100-mile detour to avoid Fort Craig and whatever Union troops were stationed there.

Abandoning their remaining wagons and leaving their wounded to Canby’s mercy, Sibley’s men began the 10-day detour with less than a week’s provisions strapped to the backs of their remaining mules. It was a trek they would remember all their lives. With little food or water, the men trudged across the barren desert, pulling their remaining artillery pieces by hand through dry gullies and over bare hills. Morale disintegrated, and what had begun as a military march quickly became an every-man-for-himself trek across the desert. Stragglers were easy prey for the merciless Dog Canyon Apaches who trailed their bloody footprints. After eight days, they completed their circle around Fort Craig and again reached the Rio Grande. A year later, Union scouts were still finding scattered pieces of bleached-out skeletons along the route.

“Not Worth A Quarter of the Blood and Treasure Expended in its Conquest”

What was left of the army returned to Fort Bliss in early May. Since the start of the expedition into New Mexico, the Confederates had suffered 1,700 casualties, many of them coming on the retreat around Fort Craig. In his report to Richmond, Sibley said bluntly: “Except for its political, geographical position, the Territory of New Mexico is not worth a quarter of the blood and treasure expended in its conquest.” High-blown talk of the gold fields and of California ports was noticeably absent. On May 14, Sibley assembled the survivors of his expedition on the fort’s parade ground, thanked them for their service, and continued his retreat to San Antonio, where the army disbanded.

Plagued by chronic illness and worsening alcoholism, Sibley went on to a number of small commands and no real achievements for the rest of the war. In 1869, he became a general of artillery for the khedive of Egypt, but later returned to the United States and died in poverty at Fredericksburg, Virginia, in 1886.

After his New Mexico service, Canby served two years as assistant adjutant general in Washington and commanded troops during the New York City draft riots in July 1863. A year later he was made a major general and given command of the Military Division of Western Mississippi. After the war, he commanded the Department of the Columbia on the Pacific Coast and was murdered by hostile Modoc Indians during a peace parlay in April 1873.

In the end, Sibley’s ambitious plan had come to nothing. It had drawn some Union troops and some attention from the war in the East and had thrilled and excited people in the South, but in the end it had produced nothing concrete. The engagement at Glorieta Pass was so disastrous to Confederate hopes that some historians have labeled it the “Gettysburg of the West.” In its way, it was at least as decisive in its far-reaching consequences. Jefferson Davis’s long-standing dream of vast gold fields, expanded slave territory, and bustling California ports had been crushed in the rocky defile at Glorieta Pass, never to be renewed for the remainder of the war.

Your lead piece of artwork needs some adjusting. There are no Saguro Cactus anywhere in New Mexico.

I believe you’re referring to the painting at the top of the story, by Don Troiani. The painting is titled “Sibley’s Texans, S.W. Confederates,” and the location depicted may not be New Mexico.

The Confederates did send a 100-man detachment to garrison Tucson from Mesilla, NM; maybe the painting is a representation of that event…