By Eric Niderost

In December 1944 the vaunted Third Reich was in its death throes, crushed by Allied forces on all sides. While Stalin’s Red Army thrust its way through Eastern Europe, Anglo-American forces had liberated France and were on Germany’s western borders. Adolf Hitler had enough resources to stage a final offensive, a last throw of the dice to stave off an inevitable and ignominious defeat.

The result was the Ardennes offensive of December 1944 to January 1945, usually called the “Battle of the Bulge,” in reference to the how the Allied line gave way to the German onslaught. The goal of Hitler’s plan, which even his generals thought was quixotic, was to seize the port of Antwerp, at the same time dividing Allied forces in two.

But thanks to the heroic resistance of such units as the 101st Airborne, and the return of good weather, which meant Allied planes could once more take to the air, Hitler’s offensive ran out of steam. Allied forces advanced, reducing the “bulge” and pushing the Germans back to their original starting point.

In January 1945, Lieutenant Herndon Inge, Jr., was serving with the 94th Infantry Division, part of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s famous Third Army. The 94th was in the process of punching through Germany’s fortified Siegfried Line (West Wall), but progress was slow, and the weather bitterly cold. Lieutenant Inge was cut off near Orscholz and captured by the Germans.

Eventually Inge found himself in Oflag (Offizierlager) XIII-B, an officers’ POW camp that held some 1,200 American and 3,000 Serbian officers at the German town of Hammelburg, near Schweinfurt. Lt. Col. John Knight Waters, Patton’s son-in-law [married to Patton’s oldest daughter, Bee], who had been captured in North Africa, was also in the camp, setting the stage for one of the most controversial episodes of the war. Patton ordered XII Corps commander Manton S. Eddy to have William M. Hoge’s 4th Armored Division form a task force (Task Force Baum) and send it on a mission 50 miles behind enemy lines to liberate Oflag XIII-B. Patton later denied all knowledge of his son-in-law’s whereabouts at the camp, but there is evidence to the contrary.

Task Force Baum—named after its commander, Captain Abraham Baum—set out on March 26, 1945. There were 10 M4A3 Sherman medium tanks, six M5A1 Stuart light tanks, three self-propelled 105mm guns, 27 half-tracks, and eight jeeps. Total command strength was a little over 300 men.

TF Baum reached its objective, but its triumph was fleeting. Baum’s command was quickly cut off by the Germans and annihilated; 26 were killed in action, and the majority were forced to surrender. Only a handful made it back to Allied lines. The rest joined the other POWs and waited for liberation, which finally came a few weeks later.

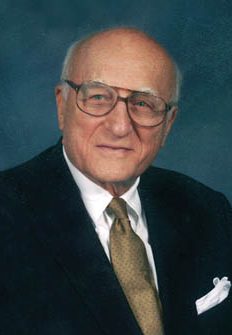

What follows is an interview with Herndon Inge, Jr., by the author.

Niderost: First, some background. Where were you born, and where did you grow up? What occupation did your father have?

Inge: I am the third of seven children, and was born in Chickasaw, Alabama, a suburb of Mobile, on March 4, 1920. My father was employed at the shipyard there during World War I and we later moved to Mobile in 1925. He later worked for the Mobile Register and the Equitable Life Insurance Company.

How was your family impacted by the Great Depression?

When the Depression came, my brother, Zeb, and I quit Murphy High School and went to work in a filling station. While working there I finished high school and went to Spring Hill College for one year, and then three years to the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa, where I had a job at the treasurer’s office.

How did you end up in the United States Army?

I graduated from the University of Alabama Commerce School with a BS degree in May 1943 and, having finished the ROTC advanced course, went to the Infantry Officers Candidate School at Fort Benning, Georgia, graduating as a second lieutenant on September 7, 1944. I was ordered to Company D, 301st Regiment of the 94th Infantry Division at Camp McCain, Mississippi.

When were you shipped to Europe?

After pre-overseas training and maneuvers at Camp McCain, the entire division sailed from New York on August 6, 1944, on the RMS Queen Elizabeth, which had been converted to a troopship. We arrived at Grennock, Scotland, six days later and went by train to Wiltshire in southern England.

What were your combat experiences prior to the Battle of the Bulge?

The 94th Infantry Division landed on Utah Beach on D-Day-plus-90, September 6, 1944. My D Company was in combat in Normandy until January 1, 1945, containing the Germans in the ports of Lorient and St. Nazaire. [Note: These hold-out garrisons, long cut off, contributed little to the German war effort.] When the Germans attacked the Americans in the Ardennes Forest [Battle of the Bulge], the 94th was sent into Germany [Rhineland] and entered combat January 1, 1945, at the base of the Saar-Moselle triangle in the Siegfried Line near Trier, Germany. The 94th was in Patton’s Third Army, and in my opinion Patton was the outstanding American general of the European campaign in World War II.

Where exactly did the 94th Infantry Division attack?

The 94th Division was deployed against a fortified section of the Siegfried Line. The Germans put up a stiff resistance to the attacking Americans. The line consisted of trenches, pillboxes, “dragon’s teeth” barriers, antitank ditches, and extensive mine fields. There were also trenches, barbed wire, and prepared concentrations of mortars, and 88mm artillery on the Western Front.

There were elements of the 11th Panzer, 123rd Infantry, and 273 Reserve Panzer Divisions there. They had been badly mauled on the Eastern Front prior to their transfer west, but they were still formidable fighters. In fact, the 11th Panzer was called the “Ghost Division” because, after their decimation, they were mere “specters” of what they had been.

Describe the events leading up to your capture.

Well, I was the forward observer for the six mortars of Company D, the heavy weapons company of the 1st Battalion of the 301st Regiment. My duties as the forward observer required me to be with the point of the column and radio back to the mortars with firing instructions.

I was attached to Company B, the rifle company commanded by Captain Herman C. Staub. They were chosen to lead the attack on Orscholz. We had stopped at the woods’ edge and looked over several hundred yards of snow-covered fields. On the far side we could see “dragon’s teeth” [concrete barriers]. Two scouts were sent out over the fields, and we were not far behind them. We made sure we stepped in their deep footprints, since we were certain the area was covered with Schu mines laid out by the Germans and hidden in the snow.

Did the Germans eventually discover you?

I remember the popping of the machine-gun bullets in the cold, gray dawn as the Germans discovered us and sprayed the area. Behind me, Schu mines exploded as the men stepped on them. As they fell, they cried for medics over the sounds of gunfire. Then the German 88s opened up on us.… I remember the shells and their deafening explosion on impact.

You were eventually cut off?

Yes, but first we had to take cover in shell holes, trenches, and woods while the German artillery and mortar fire continued unabated. We stayed the night of January 20, 1945, in a cold, narrow trench. We continually fired our rifles and carbines into the darkness and threw all of our hand grenades. We were soon out of ammunition.

What happened the next morning?

Captain Straub called the officers together to say we would try and make our way back down the road and across the open field to where the rest of the battalion had dug in. As we headed out, an 88 shell shrieked in and exploded near a tree trunk over my head. My runner, Pfc. Harley Terrell, and I crowded down to the bottom of the trench, our helmets touching. After the blast, I said, “Let’s get out of here, Terrell.” He did not move, and I saw a jagged hole in the top of his steel helmet. I lifted it up, and saw his face was bloody, and there was a big hole in his forehead. I was too shocked to cry or speak, and my stomach cramped with nausea.

When did you actually get captured?

I called to the remaining men in the trench and said, “Follow me!” Bullets were popping everywhere, and the 88s were exploding in the snow. We ran up a hill and into a concrete bunker; I found it was crowded with dead and wounded GIs. The Germans surrounded the bunker and called out in English for us to come out with our hands up. After we laid down our rifles and carbines, we were told to follow some armed Germans.

Describe the first few days of your captivity.

We were marched to the rear in the snow. An English-speaking German officer told us that we were prisoners of the German Army, and that anyone trying to escape would cause the other remaining prisoners to be shot. After that, we joined a large group of Americans who had been taken earlier.

After being loaded in open trucks, we were taken several miles to the rear and crossed the Saar River on a barge at night. American mortar rounds and artillery continued to fall on the area and roads. We traveled all night in open trucks in the snow and sleet. No food or water was provided for several days.

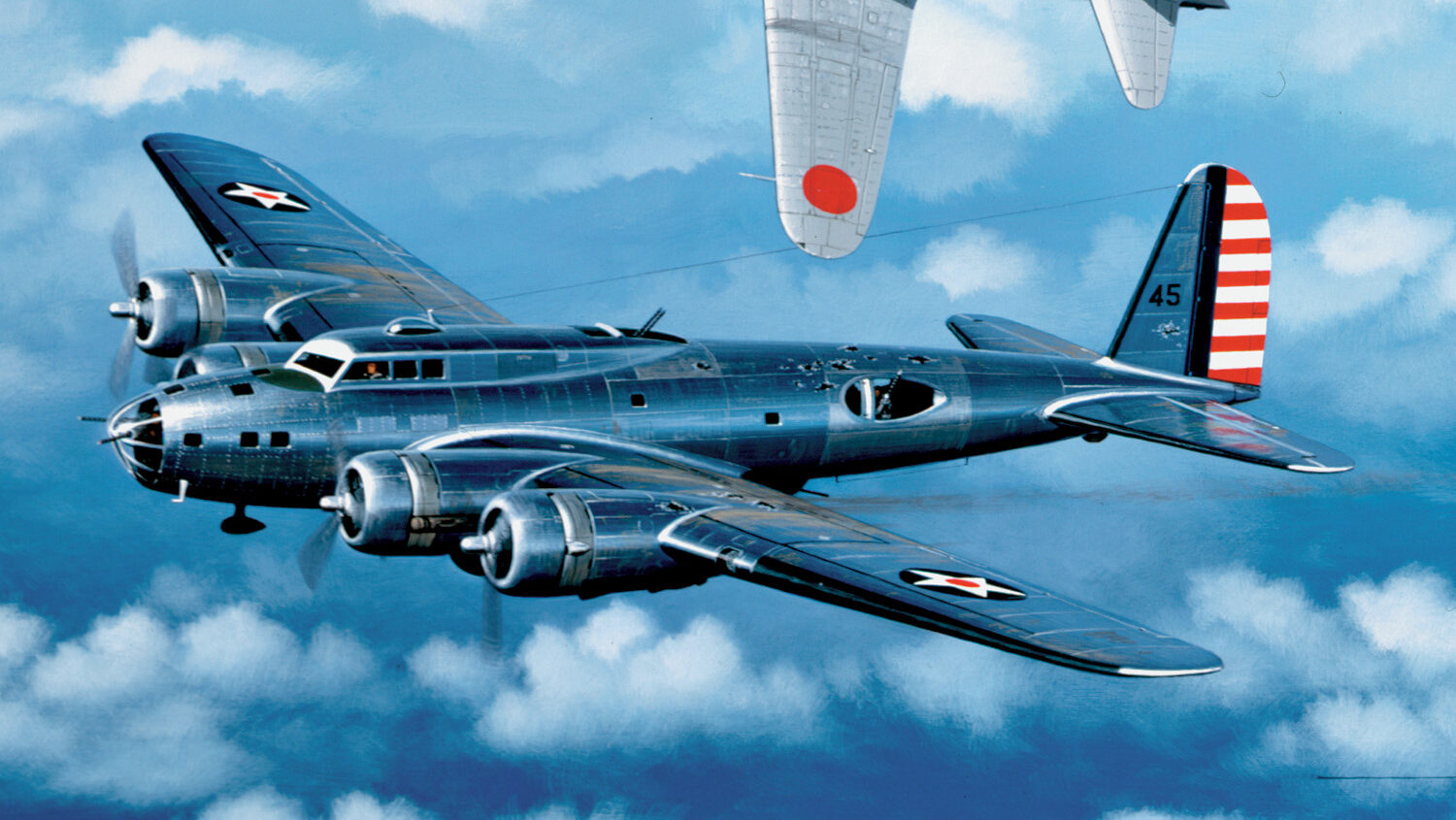

We then marched along the open, snow-covered roads, often taking cover in the ditches and woods as American P-51 and P-47 planes strafed the roads and countryside.

You eventually made it to Oflag XIII-B, near Hammelburg in Bavaria. What was the camp like?

We now found ourselves to be Kriegsgefangen [war prisoners], or “kriegies” for short. The camp consisted of tar-paper-covered buildings heated by oil-burning heaters and surrounded by barbed-wire fences with watch towers and heavily armed German soldiers. There was a large number of American prisoners at Hammelburg. [Note: Besides Battle of the Bulge American POWs, there were also Americans coming in from POW camps in Poland, primarily Oflag 64 at Szubin. They were moved to prevent their liberation by the Russians advancing from the east. One of these was Patton’s son-in-law, Colonel Waters. There were some 1,500 American officer POWs by March of 1945. In a separate but nearby camp were 4,000 Serbian POWs.]

I understand the conditions of the camp were bad. Dysentery was rife, and even in the barracks temperatures were near freezing.

Very little heat and food were provided by the Germans. As I said, the buildings were tar-paper-covered and heated by pot-bellied stoves. There was not enough firewood to keep the buildings warm, and we all huddled together for warmth.

What was the daily routine in camp, besides trying to stay warm and alive? Were there any escape attempts?

A daily news bulletin reached us some days and was read out at roll call by English-speaking German guards. There was a chess set, and games went on constantly. One person would end a game, and another person would take his seat and begin a new game. There wasn’t any attempt to escape. We were cold, weak, and hungry. Besides, we knew we would be liberated soon. We could often hear the rumble of American guns in the distance. The prisoners stayed inside mostly, though during the day there was some warmth in the sun beside the buildings.

What about the German guards? How were you treated?

The American prisoners were not mistreated. It was mainly a lack of heat, food, and comforts that we lacked. We saw very little of the German officers, but the German soldiers were in the watchtowers and well armed. Noncommissioned German officers were in charge. The German guards were not particularly friendly, but “correct.” Perhaps it was also because they knew the war would soon be over.

When was your first indication that Task Force Baum had arrived at the camp?

The first sign that the Americans were coming was seeing German trucks and tanks speeding by the compound. Later we saw American tanks [of Baum’s command] arrive, and they broke through the barbed-wire fences in several places. The Shermans fired their guns overhead and to each side. At about 2:30 in the afternoon, two big Shermans broke through the double barbed-wire fence, trailing the uprooted fence posts and wire. Shells continued to explode around the perimeter of the camp, but a joyous feeling of liberation prevailed.

Eventually you were told that, perhaps, all was not well—that Task Force Baum would have to try to make it back to the American lines, still some 50 miles away.

It was almost dark when I walked through the gaping hole in the fence and walked up the hill. The POWs were gathered around the tanks in small groups. I recall an American officer [Baum himself] getting up on a tank and stating they expected reinforcements to come up soon, but that the tanks would try and get back to the American lines.

It was discouraging, and many of the newly liberated POWs, most of them weak and hungry, trudged back to the camp. About 200, including yourself, decided to take their chances with the tanks and attempt to get back to the American lines.

It appeared that there was not enough room on the tanks for all the liberated prisoners to be evacuated. It was thought that later reinforcements and trucks would arrive [for the rest].

You and five or six other POWs clung to the topside of a Sherman tank. It proved a wild ride, when Germans starting lobbing panzerfaust [antitank] rounds at the column.

One of the rockets swooshed by my head like a Roman candle as it went past and exploded in the woods. I felt the heat, and crouched down and hung on. If the round had been a few inches closer and had hit the tank, all of us hanging on the tank would have been killed.

When the column slowed down, I climbed down and ran back 10 or 12 tanks and other vehicles and climbed up on the back of a half-track. I felt relieved I was no longer at the head of the column.

I hung on to the back of that half-track for hours. As it began to get light, Colonel Paul Goode climbed up on a tank and announced that those of us who wanted to stay with the task force and fight could do so. He, however, was opting to return to the Oflag. Most of the POWs, including myself, followed him. We walked down a narrow dirt road in the German countryside.

You had some close calls, but you narrowly missed the final annihilation of Task Force Baum.

After we had only gone about a mile, we heard the noise of a terrific battle taking place. We could also see columns of black smoke rising up over the trees. The Germans had surrounded the task force and were firing with everything that they had.

The march back to Oflag XIII-B must have been exhausting as well as bitterly disappointing.

We trudged the 11 or 12 miles back to the Oflag, and had not eaten or had a drink of water for over 24 hours. We also hadn’t slept. The German soldiers had returned to the camp, but now they were equipped for combat.

They marched us a couple of miles down the steep road to the rail yards at Hammelburg, where we were ordered to get into boxcars and were locked in. We were the targets of our own P-47 and P-51 air attacks and were given no food or water.

The next afternoon we arrived at Nürnberg at the heavily damaged rail yards and marched to a prison camp there [Nürnberg-Langwasser].

Many able-bodied POWS were taken to Nürnberg, but others—particularly the sick and wounded—remained behind at Hammelburg. Oflag XIII-B was liberated a second time on April 6, 1945, by the U.S. 14th Armored Division. How was your own liberation?

They broke through the barbed-wire fence and met little resistance, since all the German guards had left. We were marched to an open field and flown by C-47 planes to Nancy, France.

After a few days at the hospital at Nancy, we went through Paris to Camp Lucky Strike [near Le Havre] in Normandy. We were kept there for several days receiving physical exams, uniforms, then it was on to the Jonathan Trumble, a troopship, where we arrived in New York on June 6, 1945.

Muddled Legacy of Task Force Baum

During the arrival of TF Baum, Lt. Col. Waters saw the American tanks firing at gray-clad troops they assumed to be Germans; they were actually Serbian POWs. While going out with a white flag to inform the tankers of their error, Waters was shot by a German guard and taken back to the camp hospital, where a Serbian doctor did his best to save him.

Meanwhile, while trying to battle his way out of the encircling German units, Captain Baum, too, was wounded; he and Waters recuperated together in the infirmary until the camp was liberated. For his heroic but failed actions, Baum later received the Distinguished Service Cross; Waters also recovered and eventually became a four-star general.

Of the 314 officers and men in TF Baum, 26 were killed. A handful made it back to American lines while the rest were taken prisoner. All 54 of TF Baum’s tanks and other vehicles were either destroyed or captured by the Germans.

Although Patton forever maintained that he did not order the raid to rescue his son-in-law, others, including Baum, believed he did exactly that. Patton had sent an aide, Major Alexander Stiller, along with the task force, purportedly to identify Waters and make sure that he was taken to safety. Patton wrote in a letter to his wife, Beatrice: “I sent a column to a place 40 miles east of where John [Waters] and some 900 prisoners are said to be. I have been nervous as a cat… as everyone but me thought it too great a risk…. If I lose that column, it will possibly be a new incident. But I won’t lose it.”

On April 5, Patton, not yet knowing if Waters was dead or alive, again wrote to Beatrice: “I feel terribly. I tried hard to save him and may be the cause of his death.”

General Eisenhower was furious with Patton for the failed rescue attempt and the loss of so many men and vehicles. For his part, Patton was unrepentant, admitting only to the mistake of sending too small a force to perform the mission: “I can say this, that throughout the campaign in Europe I know of no error I made except that of failing to send a combat command [a full armored regiment] to take Hammelburg.”

But, as Patton’s biographer Carlo D’Este noted, “Hammelburg was the least defensible decision [Patton] ever made, and nearly as self-destructive as the slappings [of American soldiers in Sicily]…. Hammelburg has become an enduring stain on Patton’s reputation.”

I disagree. FAR more people know of the slapping incident than the Hammelburg operation. Hollywood took care of that. It is hard for me to imagine how D-Este could underestimate the “value” of the 25-years-prior movie scene and the continuing publicity regarding the slapping incident.

Hollywood or Eisenhower himself? When Patton was forced to issue a public apology, I don’t remember any Hollywood mogul/personality being even in attendance, much less the cause of it.

BobF is likely referring to the Patton movie starring George C. Scott.

…”leadership was never simply about making plans and giving orders, it was about transforming oneself into a symbol”.…

??

Patton lost 25,000 taking 20 miles of France no one wanted. That was more casualties than the Market Garden operation. Patton was a terrible General causing high casualties for little gain

During the “70s some friends and I retraced the route of Task Force Baum using the book “48 hours to Hammelburg” by Charles Whiting as a source. He was not a fan of Patton and might have been the first to write about the incident. No legitimate excuse to have fostered the mission. In another book he was critical of the Hurtgen Forest operation which was massive disaster.