By Kevin M. Hymel

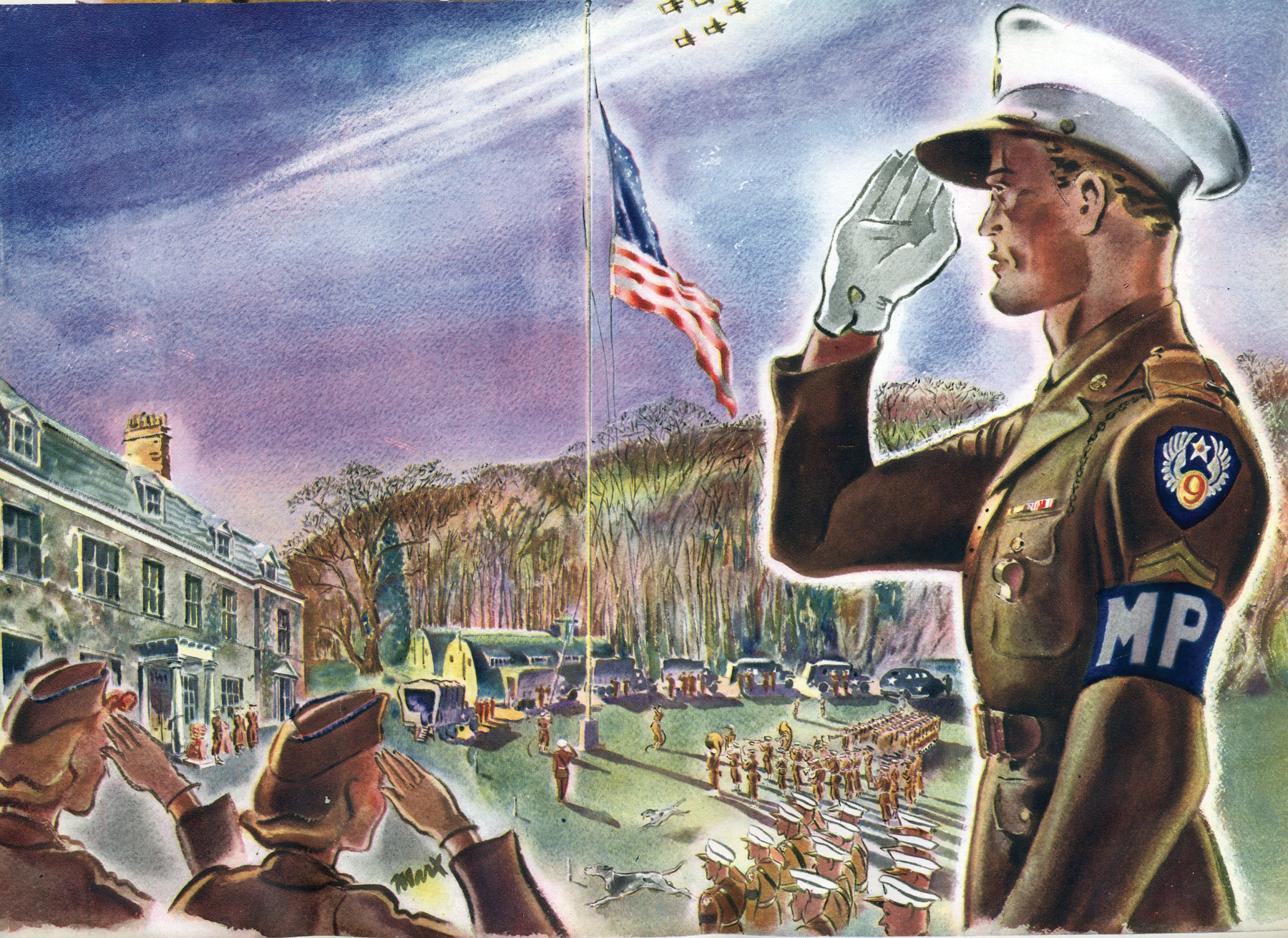

The Ninth Air Force officially arrived in England when General Lewis H. Brereton set up his headquarters in Sunninghill Park, Berkshire, on October 16, 1943. The Ninth had already had its baptism of fire in the North African desert, where it supported Field Marshall Bernard L. Montgomery’s Eighth British Army. Now it would build up to the most important action of the European Theater—the upcoming invasion of France.

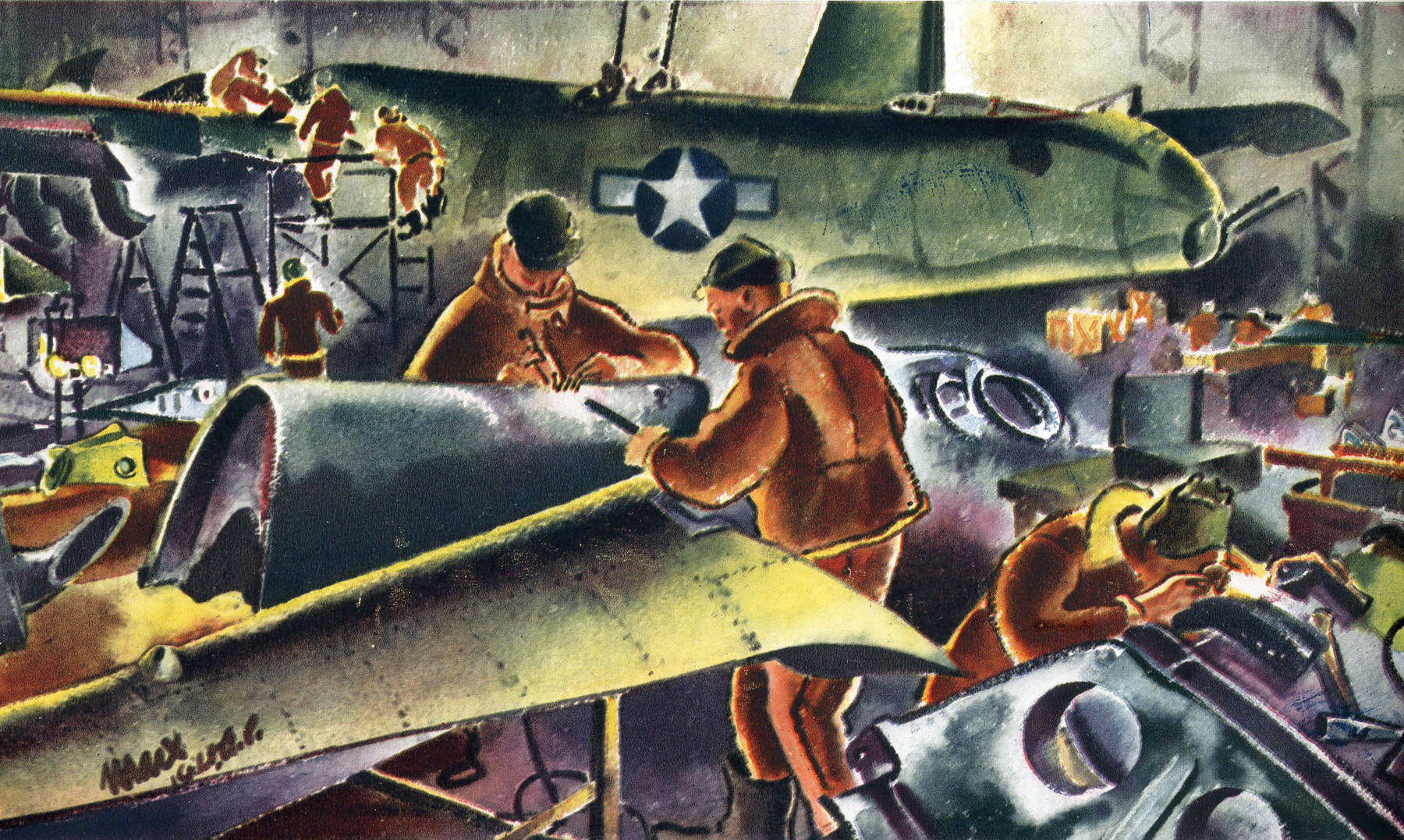

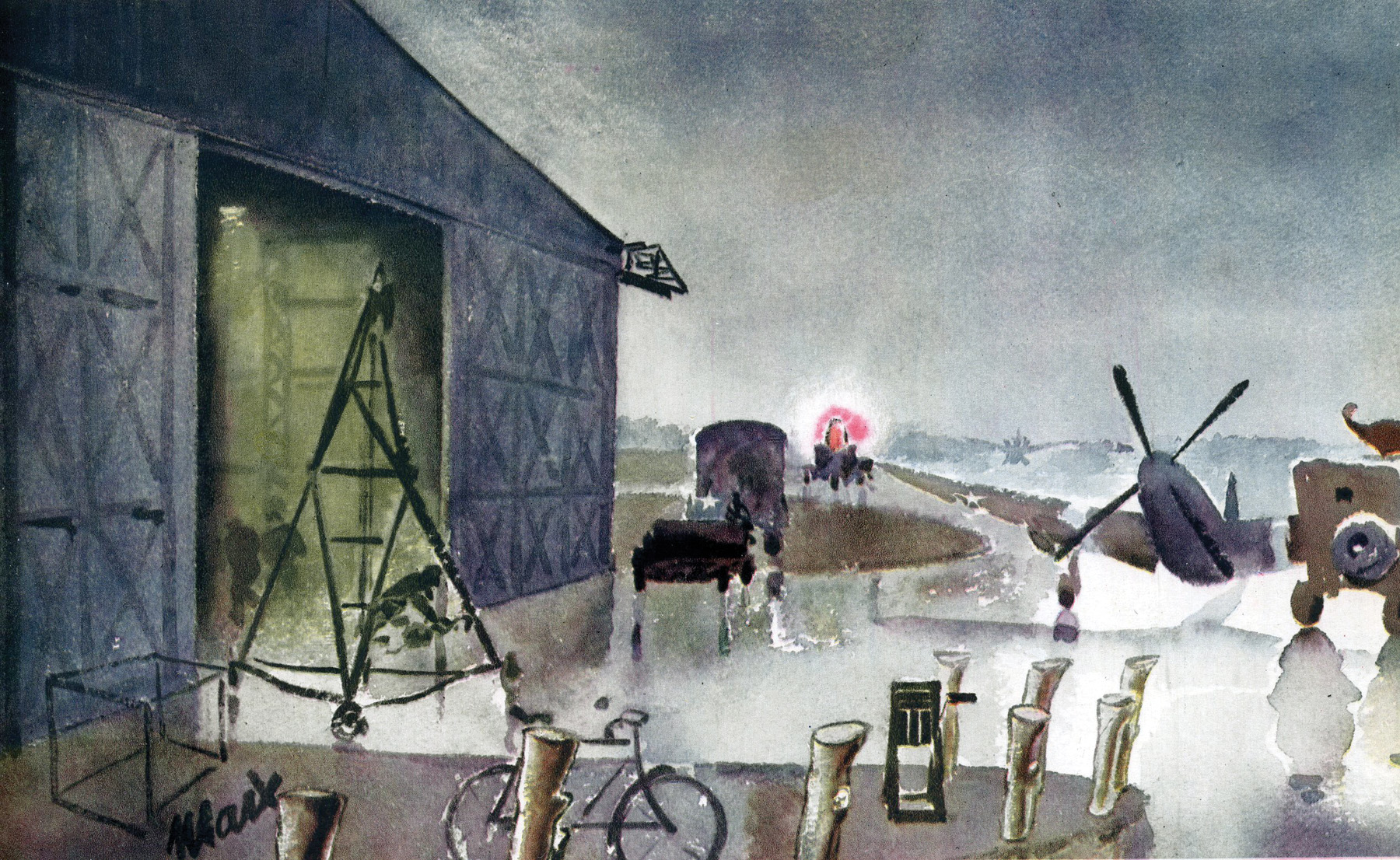

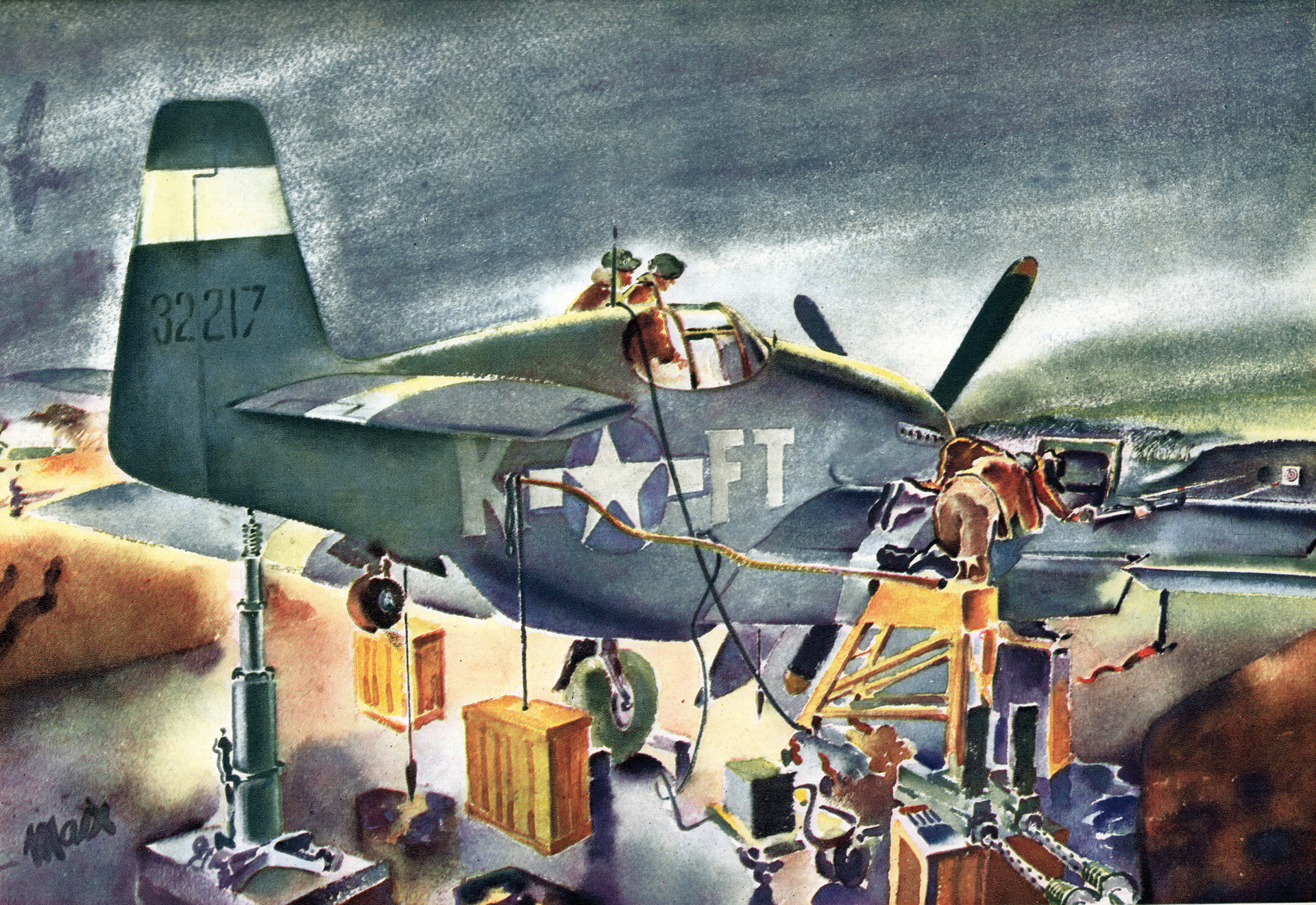

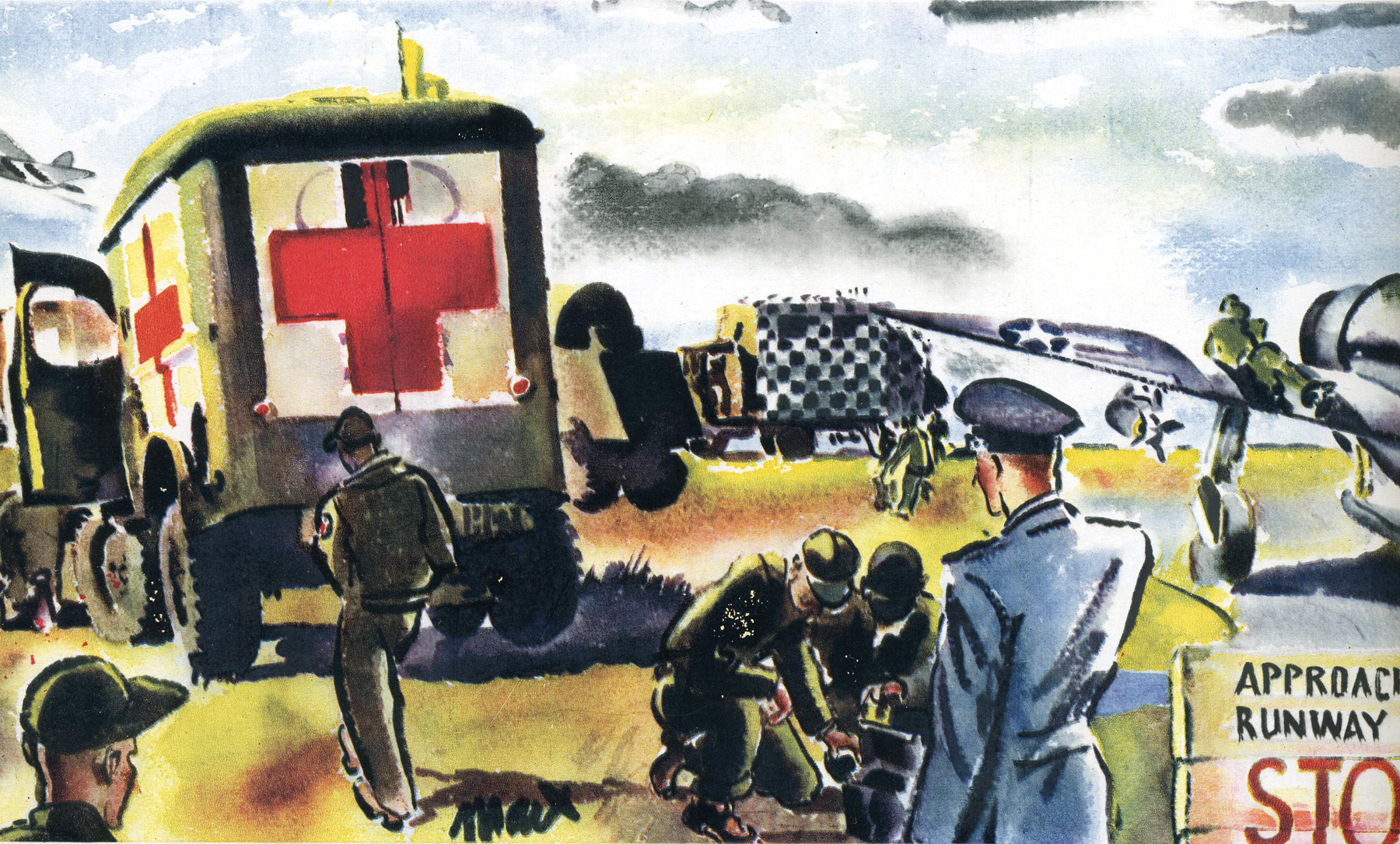

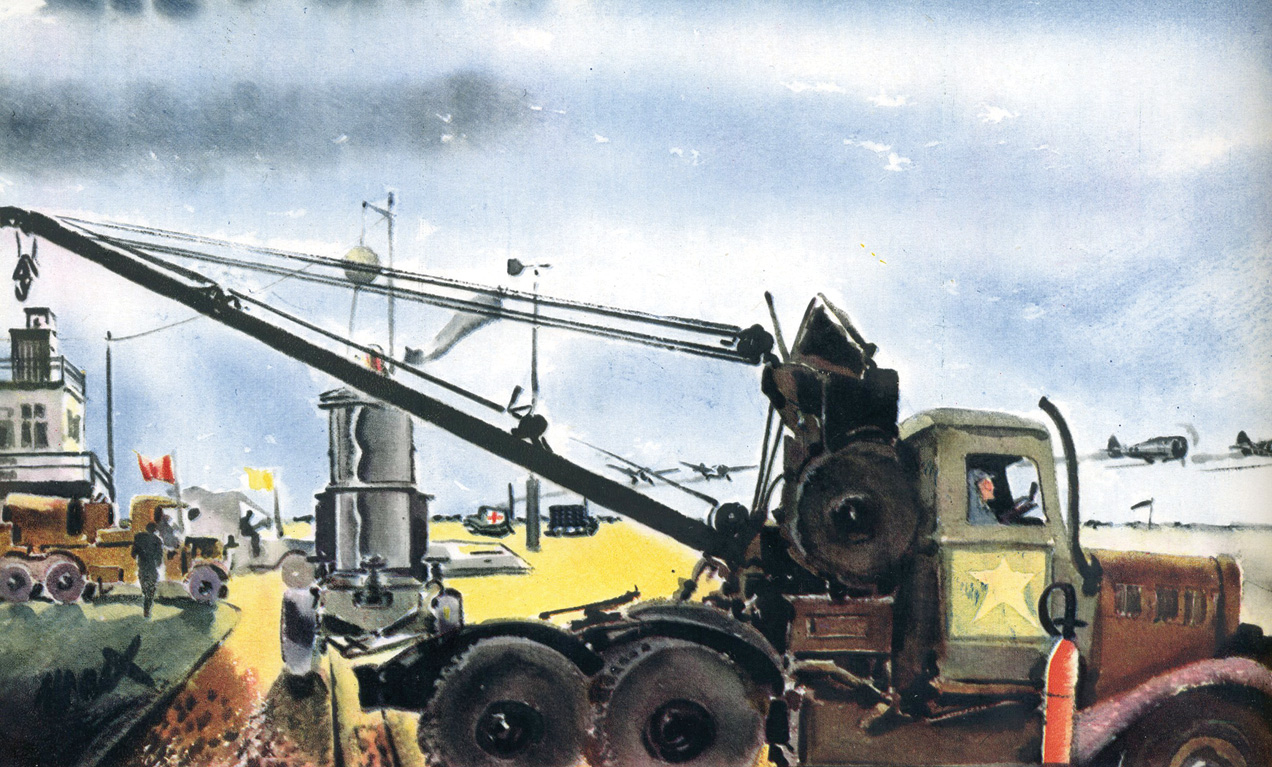

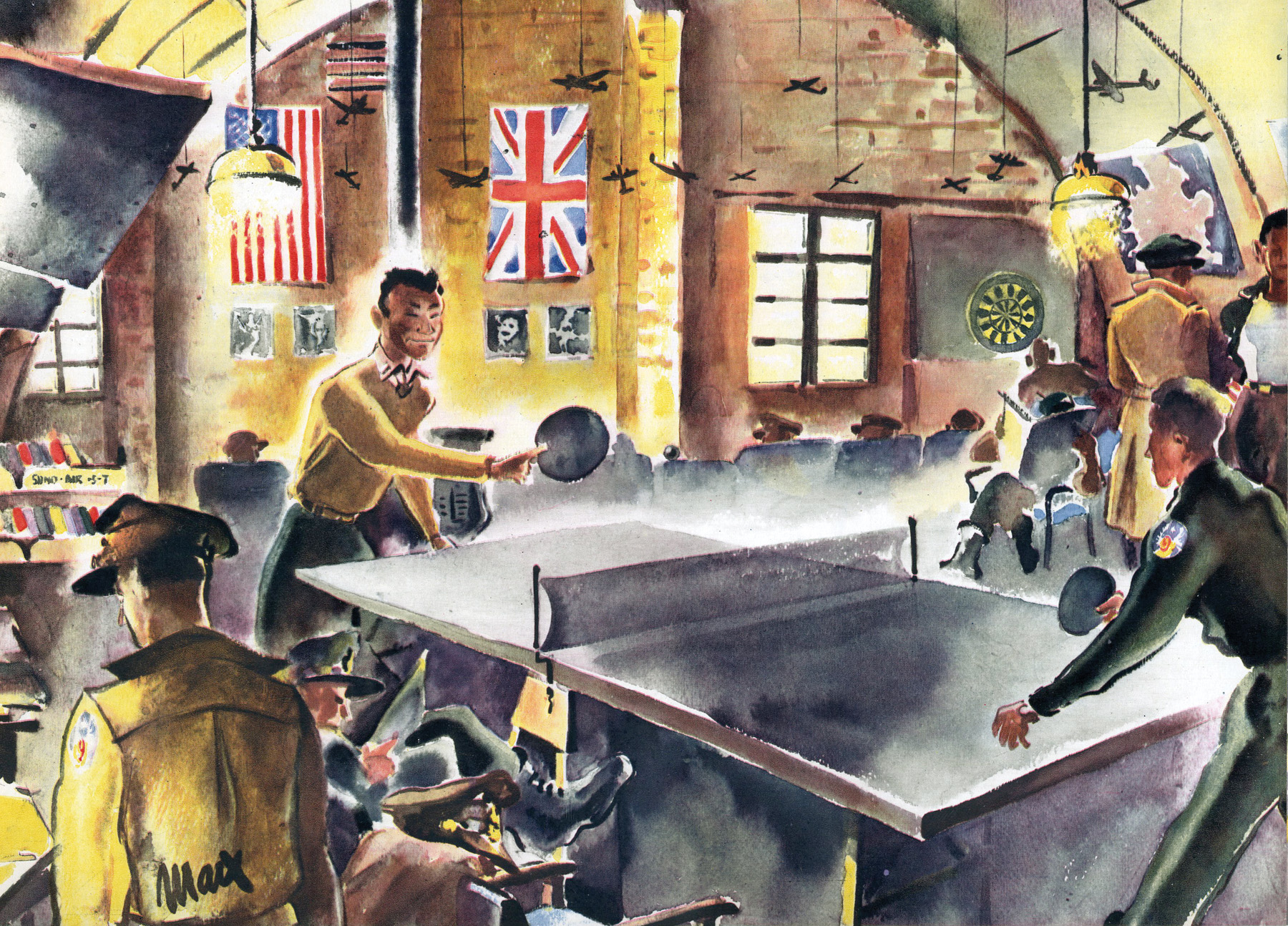

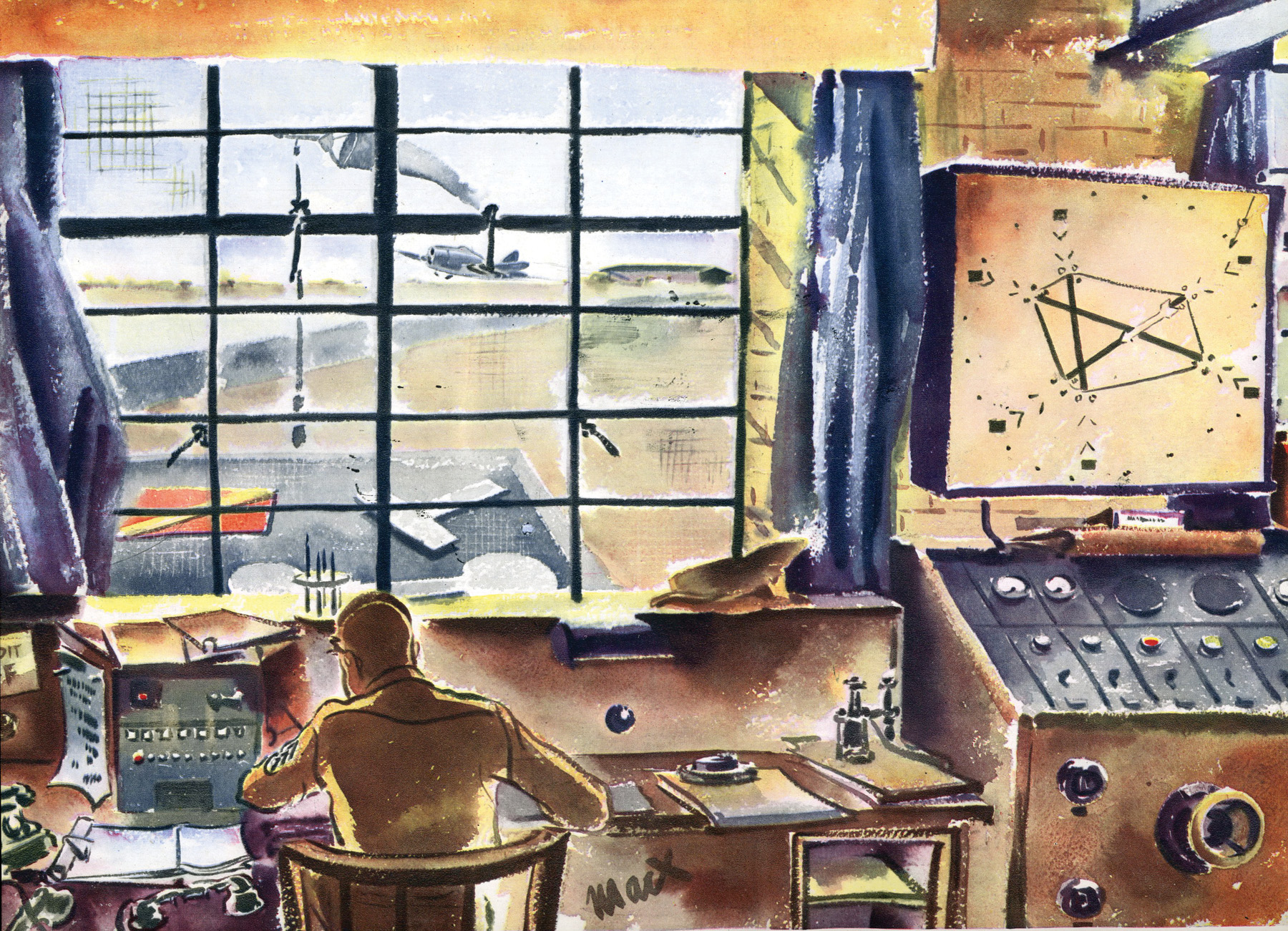

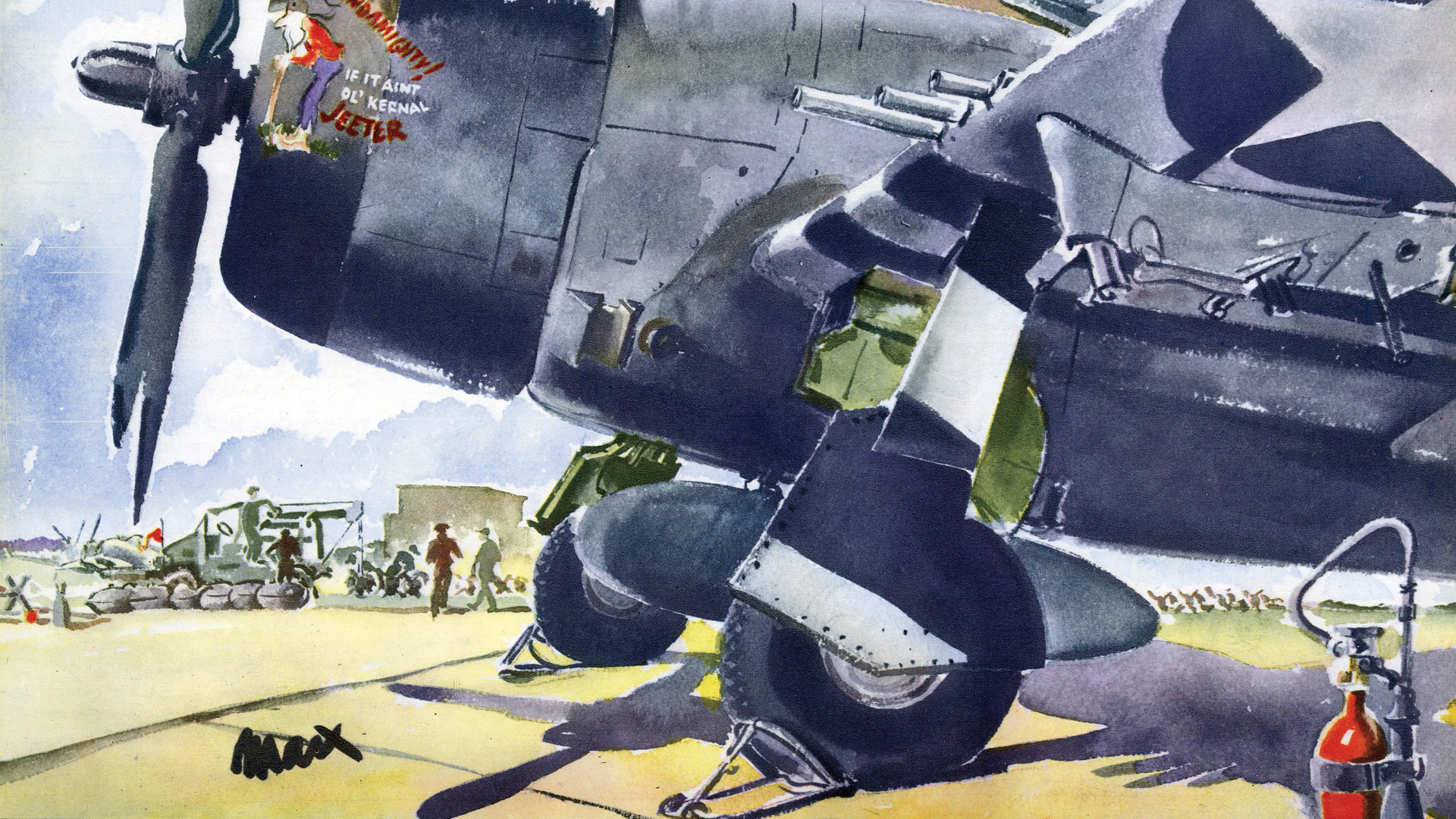

As he had done in North Africa (see WWII Quarterly, Fall 2010), Lieutenant Milton Marx, a commercial artist in civilian life and an officer attached to the Ninth’s Public Relations Office, followed the action with his paintbrush and watercolors. He captured scenes of mechanics repairing aircraft, cannibalizing parts from destroyed planes, and test-firing machine guns. He also depicted pilots enjoying downtime, controllers preparing fighters to take off, and the dramatic departure of C-47s with their cargoes of paratroopers filling the sky as they aimed for the Normandy coast on the night of June 6, 1944.

Although the Eighth U.S. Air Force seems to be the most well-known today, the Ninth saw more than its share of combat, bombing German positions in France and Belgium, hampered only by the cloudy weather so common in northern Europe. P-51 Mustangs, P-47 Thunderbolts, P-38 Lightnings, B-26 Marauders, and A-20 Havocs replaced the war-weary P-40 Warhawks, P-40D Kittyhawks, B-25 Mitchells, and B-24 Liberators that fought so hard in North Africa. The force also included a Troop Carrier Command that ferried airborne troops to their drop zones and landing zones, carried freight, and delivered wounded to hospitals.

The Ninth raced to destroy V-1 rocket “buzz bomb” launcher sites around Calais before the Germans could fire them at London. Medium bombers also attacked coastal defenses, inland strongpoints, railroad marshaling yards, and airfields. Bridges were an important target to isolate the Normandy area from Germans trying to resupply troops and equipment around the landing beaches. Planes that did not bomb or strafe were busy photographing the shoreline and enemy troop concentrations.

On the eve of D-Day, the Ninth’s sky train of C-47s formed a mighty armada,

delivering paratroopers from the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions to their drop zones. Follow-up flights brought towed gliders filled with men and equipment to the troops below. The fighter planes, released from their defensive roles, became fighter-bombers, supporting the Americans on the ground and wreaking havoc with the enemy.

After covering the landing beaches, the fighter-bombers attacked ahead of the Allied lines, strafing trains, bivouacs, enemy columns, and fortified defenses. Pilots assigned to ground units contacted air wings by radio and directed them to frontline positions. With this superb air cover, the American First and Third Armies cut off the Cherbourg peninsula and broke out at Saint Lô.

When General George S. Patton, Jr., blasted across France, he used the Ninth Air Force’s fighter-bombers to guard his flanks, something never seen before on the battlefield. With the Ninth’s help, the Western Allies entered Paris in August and crossed the Seine River.

Thanks to photographers and artists like Milton Marx, the visual history of the immense sweep of a world war has been preserved for future generations.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments