By Michael D. Hull

Operation Market-Garden, British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery’s imaginative and daring plan—reluctantly endorsed by his superior, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied forces in Europe—was complex and fraught with possible catastrophes; a hurriedly conceived blueprint flawed by over-confidence, poor logistics, and the Allied commanders’ failure to cooperate fully with the diligent and efficient Dutch resistance network. Vital intelligence from the code analysts at Bletchley Park was overlooked or shelved as the planning machinery rolled forward. For the operation to succeed, every aspect had to go according to plan. As one Allied officer observed later, “Too many things could go wrong, and most of them did.”

Market-Garden was the jump-off of the greatest armada of troop-carrying aircraft ever assembled for a single military operation. In the 263rd week of World War II, this bold Allied offensive called for one British and two American airborne divisions to seize five strategic River Rhine and canal bridges—at Son and Vegel north of Eindhoven, Grave, Nijmegen, and Arnhem—and to push armored and infantry columns northward up a narrow corridor through Holland, across the Rhine River, and into Nazi Germany.

The intention was to pave the way for a massive armored advance into the northern German plain—and the Ruhr Valley, the industrial heart of the Third Reich—before the onset of winter.

After the hard-fought Anglo-American breakouts in Normandy during the bright summer of 1944, a spirit of euphoria and optimism pervaded the Allied conference rooms and staff offices. Montgomery, the wiry, irascible hero of Dunkirk, victor of El Alamein, and invasion ground commander, bristled with confidence. “One bold thrust will take us to Berlin, and the war can be finished by Christmas,” he briskly told his staff at Laaken, near Brussels.

Market-Garden, Montgomery reasoned, was the “thunderclap” stroke required to topple Adolf Hitler’s evil empire and effect the end of World War II in 1944. A single thrust, Monty believed, would free the vital English Channel ports, outflank the fortified Siegfried Line, and open the road to Berlin. His planners and some other senior Allied commanders believed that the German armies in the West had been so decisively weakened by the actions since D-Day that they would collapse if momentum was sustained by the massed British, American, and Canadian armies.

The main obstacle was that the terrain between the Belgian border and Arnhem—the farthest objective, where a massive concrete-and-steel bridge over the Lower Rhine was to be captured by the British 1st Airborne “Red Devil” Division—was swampy and crisscrossed by numerous canals. Only one narrow road was available, and the rest of the countryside was unsuitable for an advance by heavy armored vehicles. Some Allied leaders were decidedly uneasy about the operation. Major General Stanislaw Sosabowski, the prickly commander of the Polish 1st Parachute Brigade assigned to support the Red Devils at Arnhem, angrily voiced fears that his men would be “massacred.”

It was the Arnhem bridge, 64 miles behind the German lines, that also worried Lt. Gen. Frederick “Boy” Browning, the tall, immaculate deputy commander of Major General Lewis H. Brereton’s 1st Allied Airborne Army. Pointing to the objective on a wall map during a briefing, Browning asked Montgomery, “How long will it take for the armor to reach us?” Monty replied, “Two days.” Browning answered, “We can hold it for four. But, sir, I think we might be going a bridge too far.”

Browning soon submerged his doubts and allowed himself to get caught up in the momentum and promise of Operation Market-Garden, downplaying intelligence reports of German strength in the Arnhem area. When Major General James M. Gavin, the handsome, youthful commander of the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division, expressed shock on learning that his and the other two airborne divisions would have only seven days in which to get ready for the invasion, Browning responded, “Why not? We’ve got them on the run.”

In the run-up to Market-Garden, there were continuing concerns regarding the disposition of German forces that might oppose both the airborne and ground phases of the offensive. True enough, the Dutch resistance had provided information on such prospects, and by the autumn of 1944, it appeared that the underground network of resistance fighters in the south of the Netherlands, where Market-Garden would concentrate, was well organized and ready to provide logistics, communications, and intelligence support.

The Allied invasion of Normandy had encouraged the Dutch in greater numbers to join the resistance effort, and indeed there were those who provided information that might have altered the planning of Market-Garden, postponed it, or scrapped it altogether. But Dutch reports of heavy German armor in the area were dismissed by Montgomery and Browning, as well as other high-ranking members of the Allied command.

Regardless, reconnaissance flights by RAF Spitfires had brought back disturbing photographs that seemed to back up the Dutch resistance reports. It appeared that German tanks had laagered in the vicinity of Arnhem. There had been no previous reports of any enemy armor in the area, and it was immediately believed that these were broken down or damaged vehicles moved to Arnhem for repairs.

Actually, the tanks belonged to the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions, both depleted but battle hardened during the fighting in Normandy. The divisions, including their tanks and tough panzergrenadier armored infantrymen, were right in the path of the 1st Airborne assault intended to capture the bridge at Arnhem, and the lightly armed airborne troops had only their PIAT hand-held antitank weapons.

Montgomery was aware of the presence of the German armored divisions at Arnhem but chose to discount the evidence. His miscalculation would cost the lives of many Allied soldiers and shatter the 1st Airborne Division.

Still, in contrast to some historical accounts of Market-Garden that place blame for a lack of cooperation with the Dutch resistance squarely on the ineptitude or lack of awareness among senior British commanders, there is the possibility that the hesitation on the part of Montgomery emanated from suspicions that Nazi agents had penetrated the Dutch resistance and might actually manipulate information derived from it. In conversation with Dutch Crown Prince Bernhard prior to Market Garden, Montgomery actually asserted, “I don’t think your resistance forces can be of any help to us.”

Some of the British suspicion involved Crown Prince Bernhard himself. The prince was born into the German aristocracy and married into the Dutch royal family. According to some reports, he had joined the Nazi Party and then the SS while a college student. Some theorists believe that Bernhard may have leaked the information about Market-Garden more than a week prior to the commencement of the operation while serving as a liaison officer between the British armed forces and Dutch resistance.

Sunday, September 17, 1944, was a fine, sunny day as almost 5,000 British and U.S. bombers, fighters, and C-47 transports, along with more than 2,500 Waco and Horsa gliders, streamed across southeastern England on their way to Holland. The steady thunder of their engines interrupted morning church services in mellow English towns and villages, and farmers paused in Kent and Sussex pastures to watch and wave at the armada.

At 1:30 that afternoon, an airborne army complete with light field guns, vehicles, and assorted equipment began dropping behind the German lines in Holland. It was an unprecedented daylight assault—the Market phase of the great operation. In Dutch towns, stunned German Army officers watched the sudden display of Allied might. The air drops were marred by the loss of gliders from broken tow cables, structural failures, sporadic antiaircraft fire, and landing crackups.

Meanwhile, the Garden forces—armored and infantry columns of the British Second Army’s powerful 30th Corps led by General Brian G. “Jorrocks” Horrocks—were poised along the Meuse-Escaut Canal on the Belgian-Dutch border. At 2:35 p.m., preceded by artillery barrages and supported by swarms of deadly rocket-firing Hawker Typhoon fighter-bombers of the Royal Air Force, the engines of Sherman tanks, Morris Quad trucks hauling 25-pounder guns, halftracks, armored cars, and Bren gun carriers rumbled into life. The high-spirited, charismatic Horrocks rode a jeep past his columns, shouting encouragement, and the 30th Corps rolled forward, starting its 64-mile dash up the backbone of Holland along a strategic route the American paratroopers were already fighting to seize and hold open. Horrocks ordered his corps—spearheaded by Lt. Col. J.O.E. “Joe” Vandeleur’s crack Guards Armored Division—to “drive like hell” and link up with each airborne division in turn.

The U.S. 101st Airborne “Screaming Eagle” Division led by Major General Maxwell D. Taylor was dropped to capture the nearest bridges over canals north of Eindhoven at Vegel and Son, and the objectives were taken on the first day. The division had distinguished itself in the Normandy invasion and would later gain enduring fame with its epic defense of the Belgian town of Bastogne in December 1944. General Gavin’s U.S. 82nd Airborne “All-American” Division, which had fought in Sicily, Italy, and Normandy, was dropped around Grave, south of Nijmegen, with the task of capturing bridges over the River Maas at Grave and the River Waal at Nijmegen. The first of these spans was taken on the first day.

The farthest bridge, at Arnhem over the Lower Rhine, was the objective of the “Red Devils” led by Major General Robert E. Urquhart, a burly, athletic, Scots-born veteran of the Western Desert, Sicily, and Italy campaigns who lacked airborne experience and was prone to air sickness. He had taken command of the division in January 1944. The red-bereted British paratroopers, who had never fought as a single unit, had been handed the most challenging job in Operation Market-Garden.

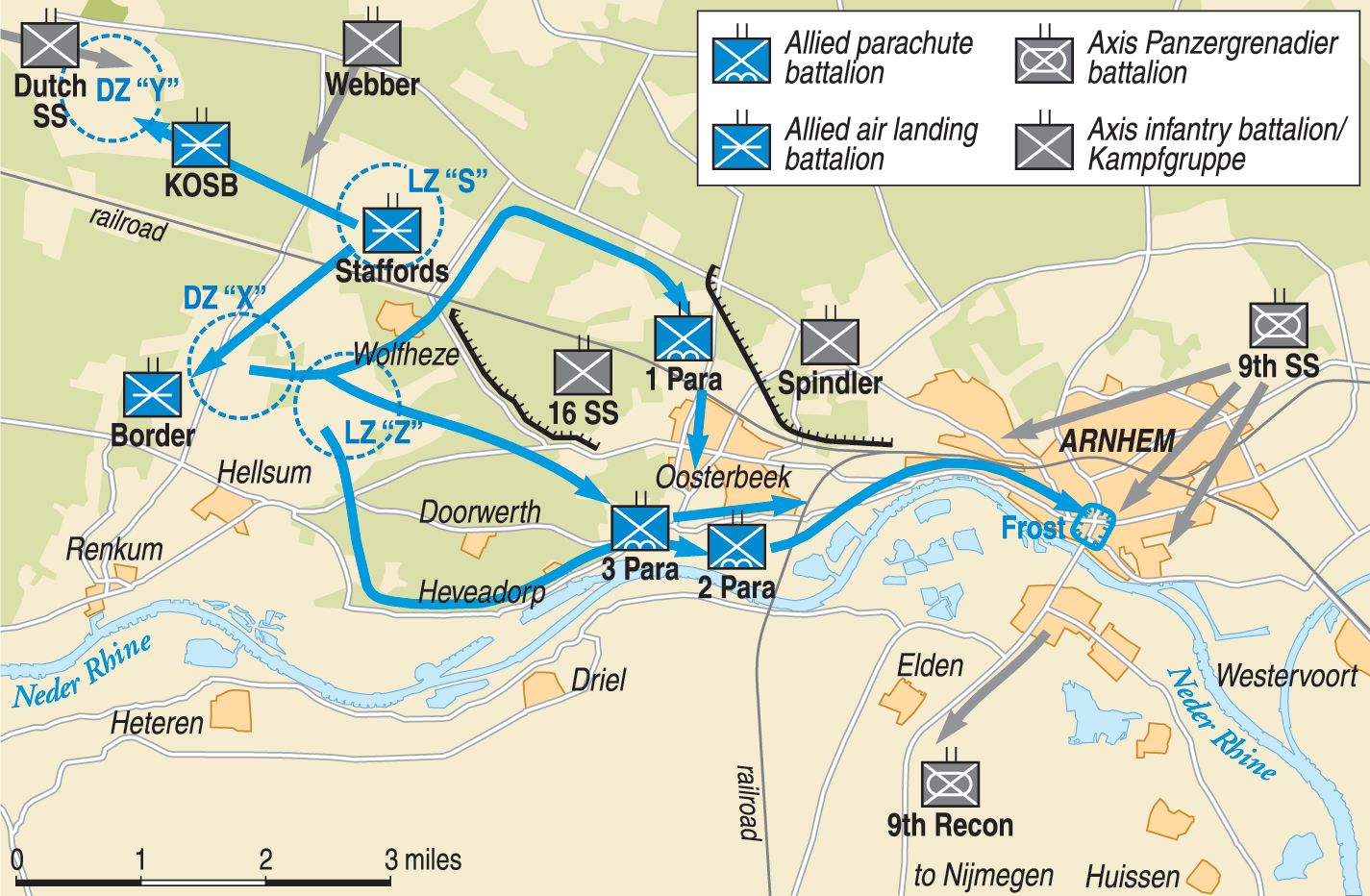

The American operations were successful, with much dash and fighting spirit displayed by Gavin’s and Taylor’s soldiers. But things began to go wrong with the Red Devils as soon as they shed their parachutes or scrambled out of their Horsa gliders. Only half of the division landed on the first day because of a lack of transport planes. Much of their vital equipment, including jeeps mounted with Vickers machine guns, was destroyed on landing; their radio sets malfunctioned, and the paratroopers were dropped between six and eight miles from Arnhem. Urquhart had requested flat, defensible terrain on which to land his men, but the few areas deemed suitable all had disadvantages. The Red Devils were armed only with light weapons—chiefly Lee Enfield rifles, Bren guns, and their PIATs.

Positioned just north of Arnhem, the recently arrived elements of the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions of the German 2nd SS Panzer Corps were under the command of General Wilhelm Bittrich, a much-decorated veteran of World War I and the 1940-44 Poland, Russia, and Normandy campaigns. Still recovering from a mauling in Normandy, his command was nevertheless a formidable opponent. Despite the numerous warnings from the Dutch resistance network and reconnaissance sorties made by RAF Spitfires, photographic evidence of the panzers’ presence had been brushed off by General Browning as well.

Along with Montgomery, Browning had suggested to an anxious intelligence officer that the camouflaged Tiger tanks, halftracks, and assault guns observed in the woods around Arnhem were probably unserviceable and manned by “young boys and old men, not first-line troops.” General Walther Model, commander of the Wehrmacht’s Army Group B in Holland and Belgium, had recently set up his headquarters in Oosterbeek, a western suburb of Arnhem. The Germans responded swiftly when the Allied transport planes appeared over Holland.

General Urquhart and his men trudged toward Arnhem, delayed by both swarms of welcoming Dutch citizens and increasing German mortar and machine-gun fire. The lack of working radio sets made communications almost impossible for the British paratroopers, and consequently there was scant coordination among battalions and companies. Ground command and control were lost for many crucial hours during the early fighting when Urquhart and his subordinate officers became separated. The usually amiable division commander grew increasingly frustrated.

When it was discovered that radio communications were not functioning, the 1st Airborne struggled to coordinate movements in enemy-held territory, contributing to the confusion of the early hours of Market-Garden. Once on the ground,1st Airborne might have availed itself of the communications capabilities of the Dutch resistance, but there was no effort to do so, perhaps for fear that resistance communications were actually controlled or at least infiltrated by German operatives.

While this theory is open to interpretation and conjecture, it is nevertheless worthy of mention. At least one former officer of the Dutch Army, Lieutenant Colonel Oreste Pinto, a liaison with SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) and counterintelligence officer working in cooperation with MI-5, British domestic security, asserted that the Dutch resistance had in fact been compromised in the spring of 1944. If accurate, this circumstance would explain the hesitation of the high-ranking British military officers to rely on intelligence received from the Dutch resistance and to minimize contact with resistance fighters once the 1st Airborne Division had been inserted.

Ultimately, only one British battalion managed to reach Arnhem. It was led by Lt. Col. John Frost, a stalwart veteran of the famous 1942 Bruneval raid and the North African campaign who blew on a hunting horn to round up his companies when they became dispersed. The men of his 2nd Battalion sprinted into the town, commandeered some houses, and set up mortar and machine-gun nests and secured the northern end of the big 2,000-foot bridge over the Lower Rhine. But the battalion could not get across the span before SS panzergrenadiers seized the other end.

Colonel Frost sent a patrol across the bridge, but it was beaten back by heavy fire. The Red Devils waited for a German thrust that they knew would come. When Waffen SS tanks and halftracks rolled across the bridge toward them, Frost’s men opened fire and stopped them with Bren guns and well-aimed PIAT salvos. The Germans called on Frost to surrender, but he snapped to an aide, “Tell them to go to hell!”

The 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions moved in through Arnhem from the north to besiege Frost’s battalion, and the Tommies were soon battling for their lives. They were cut off from the rest of the division, which was also fighting for survival against heavy odds. Casualties mounted, and ammunition began to run low. General Urquhart, meanwhile, set off with aides to try and assess the situation and reach Arnhem, but he was cut off by German armor and patrols and forced to hide in the attic of a Dutch house behind enemy lines for a critical 39 hours.

To the south, Sherman tank crews of General Horrocks’s 30th Corps linked up with the 101st Airborne Division at Eindhoven and Vegel on Monday, September 18. The British columns pushed on up the exposed highway, but enemy shellfire increased and the weather worsened. The road—dubbed “Hell’s Highway”—was surrounded by marshy ground, and there was no room to maneuver. Progress was slowed critically when the tanks and infantrymen had to wait while crippled vehicles were bulldozed off the road. The vital relief element of Operation Market-Garden fell behind schedule, and Horrocks’s initial dash was now a crawl. To the north, the 82nd Airborne Division and Urquhart’s Red Devils fought fiercely to hold their positions.

The Germans had responded swiftly to the 30th Corps ground offensive and placed infantry, machine guns and anti-tank weapons in the wooded areas along the single road toward Arnhem. The road itself was elevated, and the silhouettes of the British-manned Sherman tanks were high and distinctive. They made easy targets against the sun, and then enemy gunners picked many of them off from concealed positions. When resistance was encountered, the British columns were required to deploy infantry to clear the way, further impeding their progress.

Tuesday, September 19, was a critical day. The troops of 30th Corps managed to link up with the 82nd Airborne Division at Grave, and the British and American formations moved together toward Nijmegen. At Arnhem, where German units now blocked every entrance to the town, four battalions of Urquhart’s division fought hard but were unable to reach Frost’s battalion holding onto the northern end of the Rhine bridge. However, some units were able to push far enough and free Urquhart from his hiding place.

To the south, now 36 hours behind schedule, Colonel Vandeleur’s Shermans began clanking across a Bailey bridge hastily assembled by a Royal Engineers company. Two hours later, the Guards armored column linked up with General Gavin’s paratroopers at Grave. By noon, the tanks were on the outskirts of Nijmegen, but the road and railroad bridges were still in German hands. The American paratroopers and British tankers pushed toward the road bridge near the center of the city, but were blocked by enemy fire. The battle raged until after dark, when the Allied force dug in to wait for daylight.

Back in England that day, General Sosabowski’s Polish paratroopers waited by their C-47s at the Grantham airfield in Lincolnshire. Their commander worried that his drop zones were too far from the Arnhem bridge and that no one at the Allied 1st Airborne Army headquarters knew what was happening to Urquhart’s Red Devils because of the lack of radio contact. Fog shrouding the English Midlands refused to clear, and Sosabowski fumed over the postponements.

Early on Wednesday, September 20, companies of the 82nd Airborne Division under the command of Major Julian Cook distinguished themselves with a daring crossing of the River Waal to seize both ends of the vital bridge there before the Germans could blow it up. While Vandeleur’s tanks laid down a smokescreen and lobbed shells at the enemy on the far bank, the American paratroopers paddled under heavy fire across the 400-yard-wide river in small British canvas assault boats. Many of the soldiers had to row with their M-1 rifles and carbines. Boats were swamped or blown apart by enemy shells, and losses were heavy.

The survivors scrambled onto the riverbank, hastily regrouped, and dashed for both ends of the bridge. While some of the paratroopers battled with German snipers perched in the girders, others clambered among the bridge supports, ripping out explosive charges and tossing them into the water. Then they cheered as the British tanks rumbled across the span.

Meanwhile, after a desperate fight, Colonel Frost’s men were driven away from the northern end of the Arnhem bridge. Tanks and halftracks of the 10th SS Panzer Division ground across the bridge and pushed southward to block the Allied linkup effort. General Bittrich gave the order to “flatten” Arnhem, and 60-ton Tiger tanks lumbered through the rubbled streets, blasting buildings into piles of brick, stone, and timber, and chasing the British defenders from one collapsing structure to the next. Isolated knots of Red Devils fired back with Brens and PIATs until their ammunition ran out, and many were killed, wounded, or captured. Frost’s force was shrinking rapidly. The 9th SS Panzer Division and other enemy units encircled some of the British paratroopers in a bridgehead west of Oosterbeek.

The 30th Corps continued to attack northward from Nijmegen on Thursday, September 21, but progress was still painfully slow. Meanwhile, the Red Devils, driven out of Arnhem, now held a tenuous perimeter west of the town but still north of the Rhine. Surrounded and battered by panzer, artillery, and mortar fire, they hung on by their fingernails. As Colonel Frost’s radio operator tried frantically to reach Urquhart and the 30th Corps, the besieged battalion’s ammunition, rations, and medical supplies ran perilously low. A few RAF Dakota (C-47) transports had attempted air drops to sustain the battalion, but most of the bundles fell into German hands. The drop zones were now in enemy-held territory. Out of 390 tons of supplies intended for Urquhart’s division, only 21 tons reached British hands.

On September 21, after being delayed for two crucial days by fog in England, General Sosabowski’s 2,000-man Polish Brigade was dropped two miles south of Arnhem, on the opposite side of the Rhine. It swiftly set up a perimeter around Driel. But, when the Poles attempted that night to cross the wide river in boats, they were subjected to merciless German fire and driven back with heavy losses. They tried again the next day, Friday, September 22. The British 2nd Household Cavalry Regiment made a circuitous envelopment to link up with the Polish paratroopers, and they were joined by elements of the British 43rd Infantry Division. But time was running out.

Horrocks was still struggling to push his corps northward, and Elst, five miles north of Nijmegen, was taken that day. But the German resistance was unyielding.

The fighting in Arnhem raged on with no real change in fortune for either side on Saturday, September 23, but things were looking grim for Colonel Frost’s men. There was no sign of relief or supplies. Instead of the planned two days, the weary Red Devils had now been holding out for seven days. Their ammunition and food were scant on Sunday, September 24, and the situation was critical. General Urquhart sent out an urgent, poignant message to General Browning: “Must warn you unless physical contact is made with us early 25 September consider it unlikely we can hold out long enough. All ranks now exhausted. Lack of rations, water, ammunition, and weapons with high officer casualty rate…Any movement at present in face of enemy is not possible. Have attempted our best and will do so as long as possible.”

That day, the 30th Corps reached the southern bank of the Rhine west of Arnhem. Other corps elements, meanwhile, crossed the German border southwest of Nijmegen.

By the following day, Monday, September 25, the British paratroopers’ situation in Arnhem was clearly hopeless. So, in order to prevent the annihilation of his valiant division, General Urquhart ordered a breakout. There was to be no surrender, and as many of the surviving Red Devils as possible would be evacuated across the Rhine in small boats. A few radio operators, medical officers, and the seriously wounded were to be left behind. During the rainy night of September 25-26, about 2,400 disheartened Arnhem survivors, including General Urquhart, shouldered their packs and weapons, and started their breakout. Filthy, hungry, and tattered, they filed stealthily through woods, dodging German patrols, to the Lower Rhine. They were then ferried in assault boats manned by British and Canadian engineers to safety in an area consolidated by the 30th Corps.

Of the 10,000 Red Devils who had landed in Holland a week before, about 1,200 had been killed and 6,400—most of them wounded—taken prisoner. A few more were sheltered by Dutch families. Urquhart’s division had been almost destroyed. The total losses for the nine-day Operation Market-Garden were more than 17,000. British casualties, including 30th Corps men and glider pilots, totaled 13,226. The U.S. 82nd Airborne Division lost 1,432 men, and the 101st Airborne Division lost 2,118.

As for the Dutch resistance, the entire story of its security or compromise and the failure to fully leverage its potential contribution to Market-Garden will remain a subject for historical discussion.

Nevertheless, whether the Nazis had penetrated the organization or not seems to have had little bearing on the reprisals that the Nazis took against those identified as working for the Allies. Estimates of the number of Dutch resistance fighters killed by the Germans run as high as 2,000. Most of these losses were probably sustained between 1944 and 1945, when the resistance movement became more militarily active. One cemetery near the town of Bloemendall is the final resting place of nearly 400 members of the Dutch resistance who lost their lives during World War II.

Arnhem was a historic feat of arms. The British paratroopers fought without armored or artillery support against a force about four times as large. One press dispatch called it “the most tragic and glorious battle of the war.” But it was also a defeat that sealed the fate of Operation Market-Garden and proved a costly lesson on the perils of hasty strategic planning. With less than a quarter of the 1st Airborne Division left intact after the battle, it saw no more action for the rest of the war.

Even after the failure of the 30th Corps to reach Arnhem and “the bridge too far,” the severe mauling of Urquhart’s Red Devils, and the overall heavy losses, Field Marshal Montgomery staunchly defended the campaign. “In my—prejudiced—view,” he declared, “if the operation had been properly backed from its inception, and given the aircraft, ground forces, and administrative resources necessary for the job, it would have succeeded in spite of my mistakes, or the adverse weather, or the presence of the 2nd Panzer Corps in the Arnhem area. I remain Market-Garden’s unrepentant advocate.”

Interestingly, Prince Bernhard commented, “My country can never again afford the luxury of another Montgomery success.”

Reflecting on Operation Market-Garden, General Eisenhower wrote in 1948, “The attack began well, and unquestionably would have been successful except for the intervention of bad weather. This prevented the adequate reinforcement of the northern (Arnhem) spearhead and resulted finally in the decimation of the British airborne division and only a partial success in the entire operation. We did not get our bridgehead (across the Rhine), but our lines had been carried well out to defend the Antwerp base…The British 1st Airborne Division, in the van, fought one of the most gallant actions of the war, and its sturdiness materially assisted the two American divisions behind it, and the supporting ground forces of the (British) 21st Army Group, to take and hold important areas.”

The irrepressible Montgomery summarized the controversial operation in 1958. He said, “We did not, as everyone knows, capture that final bridgehead north of Arnhem. As a result, we could not position the Second Army north of the Neder Rijn at Arnhem, and thus place it in a suitable position to be able to develop operations against the north face of the Ruhr. But the possession of the crossings over the Meuse at Grave and over the Lower Rhine (or Waal, as it is called in Holland) at Nijmegen, were to prove of immense value later on; we had liberated a large part of Holland; we had the stepping-stone we needed for the successful battles of the Rhineland that were to follow. Without these successes we would not have been able to cross the Rhine in strength in March 1945—but we did not get our final bridgehead, and that must be admitted.”

Monty gave four reasons why he thought that Operation Market-Garden “did not gain complete success.”

First, the operation was not regarded at supreme headquarters as the spearhead of a major Allied movement on the northern flank to isolate and finally occupy the Ruhr—the one objective in the West which the Germans could not afford to lose. Ike ordered that this be done, said Montgomery. He thought it was being done, but it was not.

Second, because of the lack of satisfactory drop zones, the Red Devils were airlifted too far from the vital objective, the Arnhem bridge, and it was several hours before they reached it. Any element of surprise was lost. “I take the blame for this mistake,” said Monty. The third strike against the operation, he said, was the weather. “This turned against us after the first day, and we could not carry out much of the later airborne program,” he recalled. “But weather is always an uncertain factor, in war and in peace.”

The fourth element jeopardizing Market-Garden was the presence of the 2nd SS Panzer Corps in the Arnhem area. “We knew it was there,” said Monty, “but we were wrong in supposing that it could not fight effectively; its battle state was far beyond our expectation. It was quickly brought into action against the 1st Airborne Division.”

Montgomery apparently made little or no mention of a more active role that might have been played by the Dutch resistance.

And so, in the wake of the defeat, the controversy of Operation Market Garden remains the subject of debate among historians and military planners to this day.

The late Michael D. Hull wrote extensively for WWII History on a variety of topics. He resided in Enfield, Connecticut.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments