By Brent Dyck

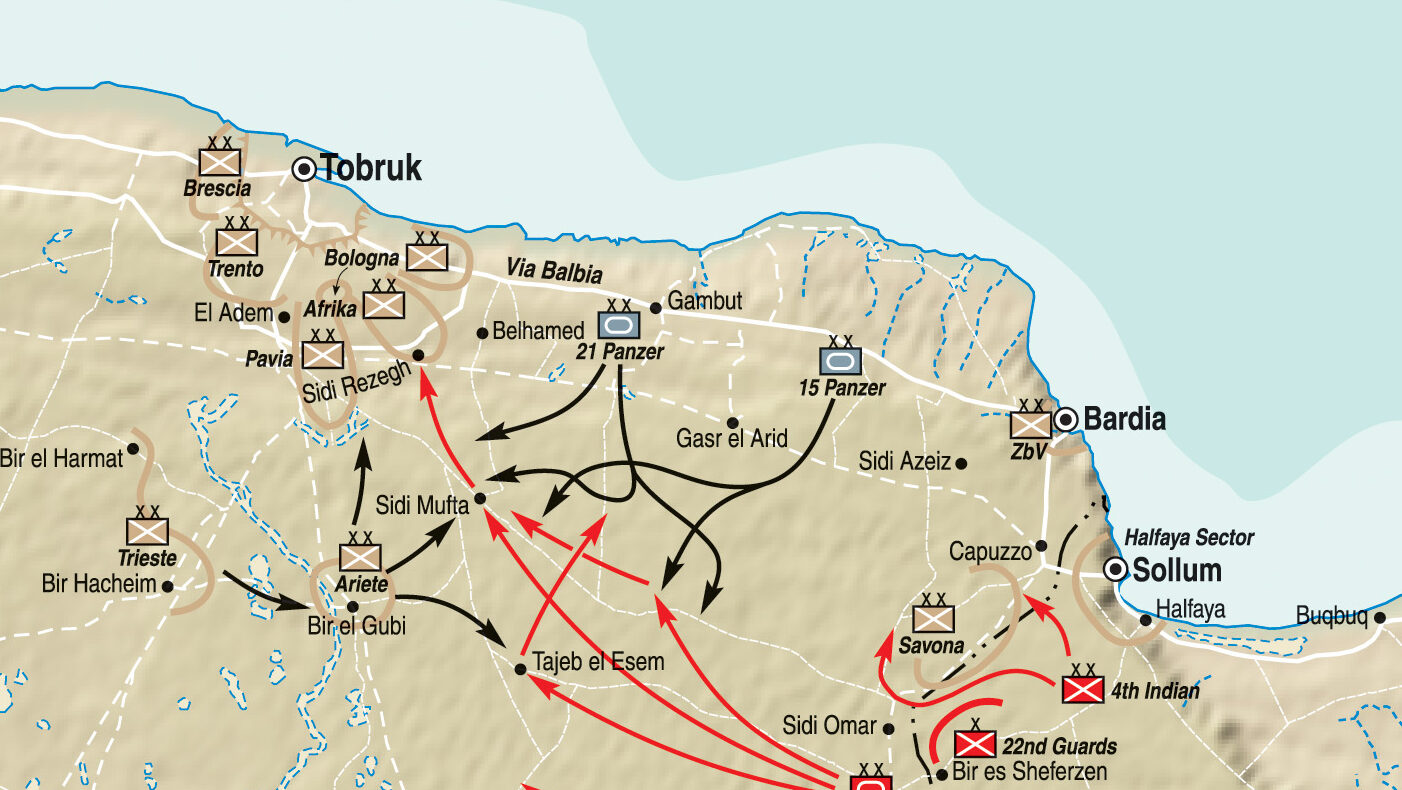

After D-Day, the Allied armies slowly advanced across Europe and pushed the German army back. Paris was liberated on August 25, 1944, the Belgian capital of Brussels fell on September 3, and the important port of Antwerp was taken two days later. The capture of Antwerp was vital, as it now gave the Allies a port where they could offload 40,000 tons of supplies a day to prepare for the final push into Germany.

On September 16, Adolf Hitler called his generals together at his Wolf’s Lair headquarters in Poland and made an announcement. Banging his fist on a map of Europe, he declared, “I am taking the offensive. Here—out of the Ardennes! Across the Meuse and on to Antwerp!”

Hitler was inspired by the example of Frederick the Great two centuries earlier. During the Battle of Lossbach in the Seven Years War, Frederick the Great’s Prussian army had defeated his enemies. This caused the alliance against him to split up, and Prussia eventually won the war. Now Hitler hoped that by attacking through the Ardennes and taking Antwerp, the alliance against him between Great Britain and the United States would also dissolve. Once the Allies were defeated in the West, he could turn all his attention to the Soviet juggernaut in the East, where he hoped to defeat the Red Army with his new Vengeance weapons.

Over the next two and a half months, the German high command managed to pull off one of the greatest logistical feats of World War II. By using new conscripts from prisoner-of-war camps and troops from the navy, the air force, the home guard, and even the Hitler Youth, the Germans managed to create 25 new divisions. They then managed to move almost 300,000 men and 2,800 new armored vehicles to their jumping-off points on the Siegfried Line along the Belgian border, traveling at night under the cover of darkness. Hitler’s great offensive was slated for mid-December 1944, when poor weather conditions would favor the Germans and hamper the Allies’ air superiority. This epic fight that followed the initial German attacks would later become known as the Battle of the Bulge.

The failure to notice this buildup of enemy troops was one of the biggest intelligence failures in American military history. The Allies believed that the Germans did not have the manpower, the equipment, or the fuel to launch a major strategic offensive against them. The Allies were so sure that the Germans could not launch an attack that Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, commander of the 21st Army Group, requested permission from General Dwight Eisenhower, commander of Allied forces in Europe, to return home to England for Christmas since the front lines were so quiet and inactive. Additionally, nobody expected an attack through the rugged, dense Ardennes Forest, even though, as historian Antony Beevor has wryly noted, “the Germans had used this (same) route in 1870, 1914, and 1940.”

One of the divisions earmarked to spearhead the surprise attack was the 3rd Fallschirmjäger (Paratrooper) Division. The 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division was an elite unit that had been rushed to Normandy after D-Day to help stop the Allied invasion. It had fought so tenaciously that it had delayed the U.S. 29th Infantry Division’s capture of the important city of St. Lo for some time. In September, the 3rd Fallschirmjaeger Division was transported to Holland to defend the town of Arnhem against British and Polish paratroopers during Operation Market Garden. Now the division moved to the Siegfried Line, where its job was to break through the front lines to facilitate the advance of Kampfgruppe Peiper, led by SS Obersturmbannfuhrer (lieutenant colonel) Joachim Peiper, and his armored spearheads through the Ardennes and north to capture Antwerp.

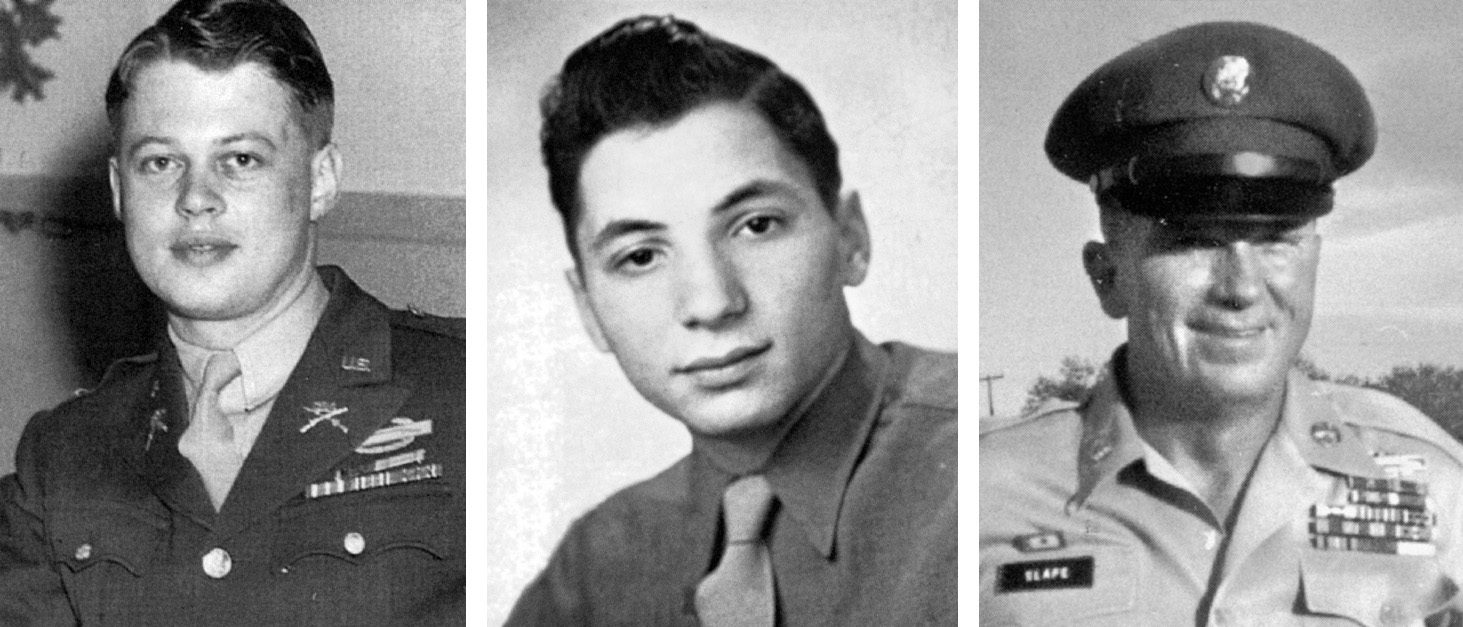

The German soldier had very little respect for the fighting capability of the average American soldier. One of them wrote that the American soldier “doesn’t attack without aircraft and tanks. He’s too cowardly for that.” Another German soldier wrote, “The American infantryman isn’t worth a penny.” This opinion of the American soldier would soon be changed by the actions of the troops of Lieutenant Lyle Bouck’s 394th I&R (Intelligence and Reconnaissance) Platoon of the 394th Infantry Regiment of the 99th Division at the Battle of Lanzerath.

The I&R platoon was sent to the Belgian village of Lazeranth in early December. Lanzerath was only a few miles from the German positions on the Siegfried line, and the platoon was moved there because it was an undermanned section of the American front—located in a gap between the 99th and the 2nd Infantry Divisions. Lanzerath was tactically significant because it lay on a north-south road that led to the 394th Regiment’s Headquarters at Hunningen, and then to the 99th Division’s headquarters at Butgenbach.

I&R platoons were not meant to be frontline soldiers. Their job was to stay in the shadows and carry out reconnaissance patrols to gather information about the enemy’s strength and positions. However, the front was so undermanned that Bouck’s I&R platoon was needed to hold the line. Usually an I&R platoon is made up of 25 soldiers, but since some of his men were needed at regimental operations and regimental headquarters, Bouck’s I&R platoon was down to 18 men when it was sent to Lanzerath.

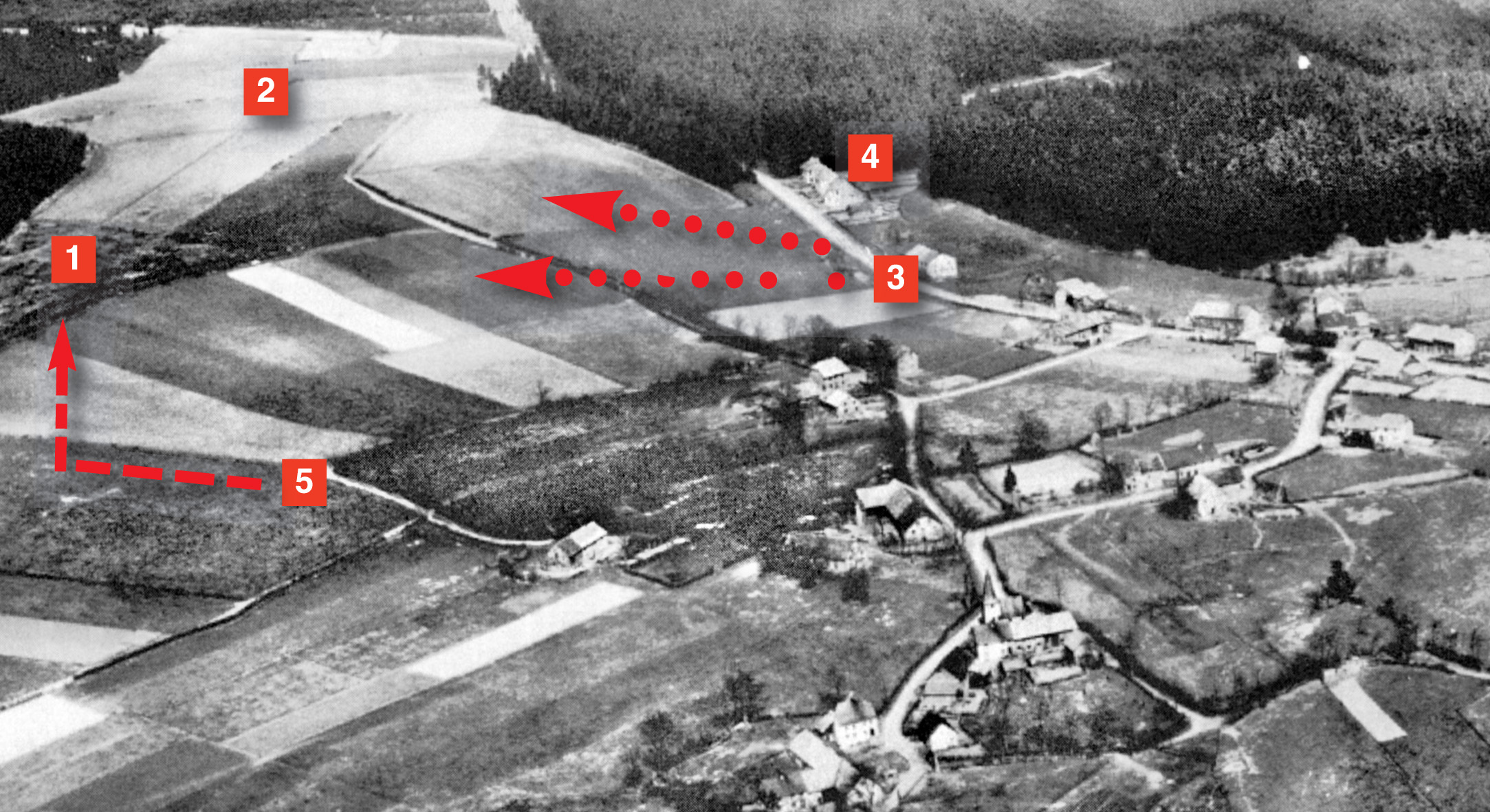

Bouck’s soldiers took their places in two- and three-man dugouts that had already been built into the side of a hill behind the town. Bouck had his men cut down trees and place them on top of the dugouts for additional protection against possible German shelling. In front of the dugouts was an open pasture about the size of two football fields and intersected midway by a barbed- wire fence. “We all felt that the position we had been put in was a very dangerous one due to the small number of men we had and the terrain,” recalled Corporal Sam Jenkins. “Also, we did not have too many weapons.”

Realizing that they needed more firepower, Bouck traded some German identity cards with the regimental ordnance officer for an armor-plated Jeep mounted with a .50-cal. machine gun. Bouck drove it back to the platoon’s position and placed the Jeep in the middle behind the nine dugouts for extra fire support.

At 5:30 am on December 16, 1944, the morning silence was broken by terrific explosions as German artillery let loose all across the front on the American positions. At first light around 8 am, the first wave of the 9th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment emerged from the woods at the bottom of the hill. Bouck called regimental headquarters and requested artillery support. He gave the coordinates, but the artillery never came since he and his men were outside of the 99th Division boundary and artillery support was needed elsewhere.

The German paratroopers now began to cross the fields in the thick snow right in front of the dugouts. Bouck realized that he was outnumbered—by as much as 20 to 1. Private Risto Milosevich exclaimed, “My God, the whole German Army is here.”

Bouck informed regimental headquarters of his situation and asked what he should do: stay or pull back and reinforce a larger force. As Bouck later recalled, “The answer was loud and clear: ‘Hold at all costs!’”

Just then a jeep pulled up carrying Lieutenant Warren Springer and his four-man artillery spotter crew. Did Bouck need any help? Bouck was glad for any help he could get and sent them to man the dugouts.

Bouck told his men to wait to fire until he gave them a signal. Just as he was about to give the signal, a young blonde-haired girl emerged from the village and spoke to the lead group of German officers. Bouck refused to give the order to fire. He waited until the little girl was safely back in her house and then he ordered, “Open fire!” and dropped his arm.

The platoon and the artillery observers fired their machine guns through the slits of their dugouts at the unsuspecting Germans moving toward them. Private William Tsakanikas jumped onto the jeep and swept the battlefield with the .50-cal. machine gun. The armor-piercing bullets from the .50-cal. put dinner-plate sized holes in the Germans. Finally, the battlefield became quiet. The attack had lasted less than 10 minutes, but all the attacking Germans had been killed, wounded, or forced to retreat. Dead bodies hung on the barbed-wire fence, and blood turned the snow red.

The Americans had suffered, as well. Three platoon members were captured trying to get to regimental HQ to get reinforcements. Private Joseph McConnell had also been shot in the right shoulder, but this did not deter him and he continued to fight.

Just before 11 am, the Germans launched their second attack. Once again it was a frontal assault on the American position across the open field. This time Private Milosevich took his turn on the .50-cal. machine gun. He later said, “I figured we were going to get it (since we were so outnumbered), so I was going to take all the Germans with me I could.”

One German soldier managed to crawl within 20 yards of one of the dugouts and fired his Schiessbecher, or rifle grenade, into the slit of the dugout. The grenade did not explode, but it hit Private Louis Kalil in the face, fracturing his jaw in three places and embedding his lower teeth into the roof of his mouth. Kalil’s dugout partner, Sgt. George Redmond, put sulfa powder on the wound and wrapped his face with gauze.

“If things get to where you can take off, then take off,” Kalil told Redmond, knowing that the Germans were inching ever closer.

“We’re staying here together,” Redmond replied. Redmond refused to leave his fellow soldier and friend behind. They both grabbed their weapons and kept firing through the slits. Everything went quiet. The Germans retreated to the woods at the bottom of the field.

After this attack, a German officer lifted a white flag and walked up the hill. Bouck ordered his men not to fire. The officer asked if his medics could remove the wounded from the field. Bouck agreed. There were so many wounded German soldiers that it took more than an hour for the medics to clear the battlefield.

Around 2:00 pm, the German paratroopers launched their third frontal assault on the American position. Once again, the Americans returned fire and held their ground. This time Sergeant Bill Slape manned the .50-cal. machine gun. He fired so many rounds at the enemy that the gun overheated and finally seized up.

Suddenly, artillery observer Billy Queen cried out. He had been shot in the stomach. With no medic or surgical equipment available, Queen died shortly afterward. Unable to dislodge the Americans and with their casualties mounting, the Germans called off their attack after a few minutes. Bouck was now down to 18 men, and the platoon was running low on ammunition.

Shortly after 4:00 pm, the Germans launched their fourth attack of the day against the I&R platoon. This time, the Germans had learned from their previous mistakes and spread out to outflank the Americans. Sergeant Slape noticed that Germans had made their way behind them. He remembered, “I started out of the bunker by the rear entrance and a German shot a hole in my field jacket. He was about 20 yards to the left rear of the bunker. There were three of them. A grenade handled the situation nicely.”

Radio operator James Fort had strung up several fragmentation grenades around his dugout. Fort waited until the Germans had moved within the perimeter and then pulled the wires attached to the pins. The grenades exploded, killing several German soldiers.

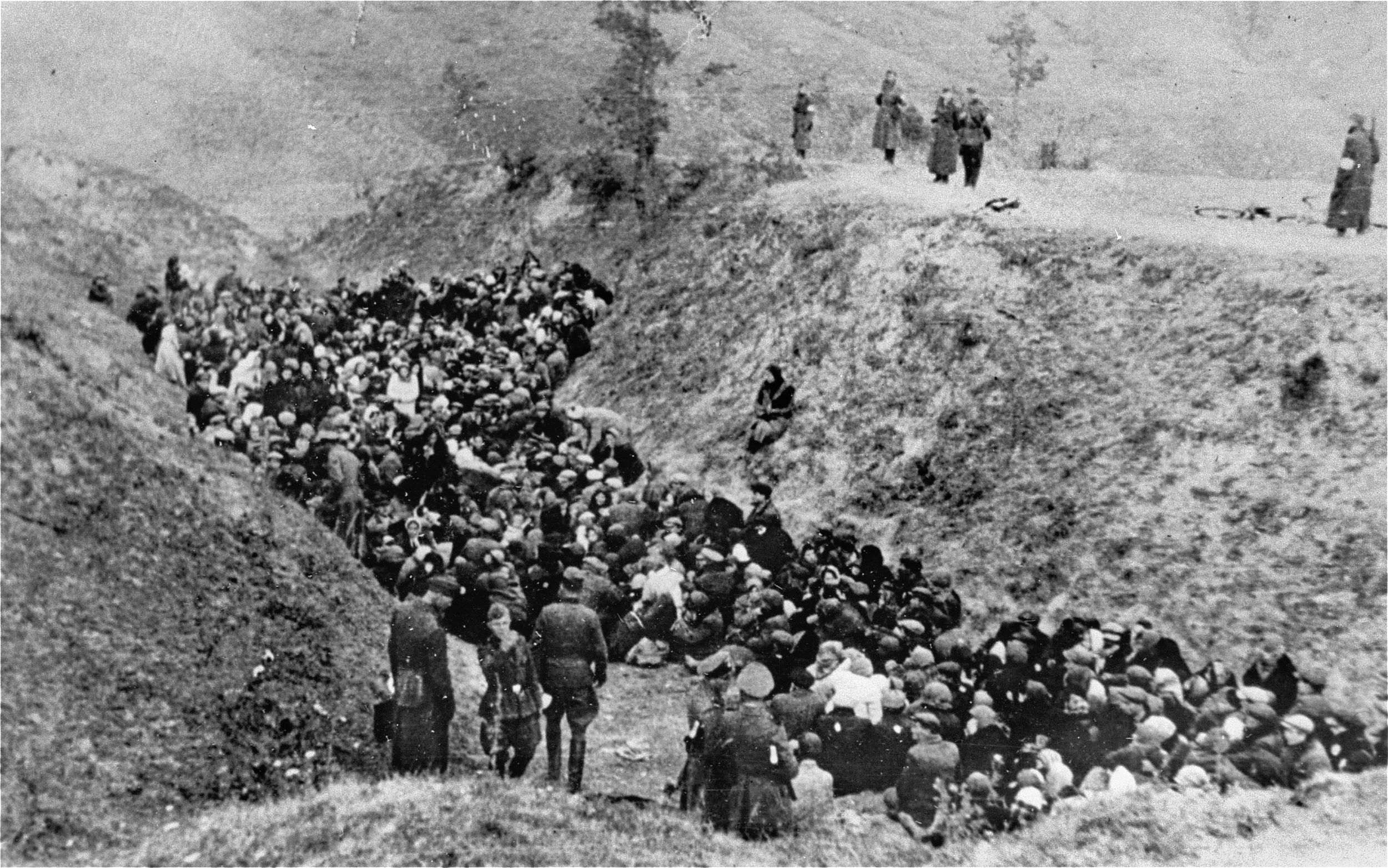

Finally, surrounded and out of ammunition, the American soldiers surrendered and emerged from their dugouts. Private Tsakanikas had been shot five or six times in the face. He had lost his right eye, his right jaw was fractured, and pieces of bone were lodged in his brain. Bouck had been shot in his leg, but all the members of the platoon were still alive. The exact number of German casualties is unknown. Beevor estimates that over 400 paratroopers were killed or wounded that day by the I&R platoon and the artillery observers.

As the Americans walked down the road toward the town with their hands up, a German soldier suddenly yelled, “Halt!” in English.

Bouck stopped. The German pointed his machine gun in Bouck’s stomach.

“St. Lo? St. Lo?” the German asked, wondering if Bouck had been at the battle in France that had killed so many of his fellow soldiers.

“Nein, Nein,” replied Bouck.

Not convinced, the German pulled the trigger. Bouck closed his eyes and waited to die. Amazingly, nothing happened. The gun jammed. Bouck was still alive.

He was put back in line and marched with his men to a cafe in the town, where they waited. The Germans brought their wounded into the same cafe. Private Milosevich recalled the scene many years later. “(Our boys) were really hurt. Boy, they were hurt. Tsakanikas at least three bullets in his face; Kalil, a grenade in his face; McConnell hit in the shoulder. But they never said a word. There was no crying. Downstairs, they had more German wounded, and they were screaming. The super race was screaming.”

They had fought so tenaciously that the Germans refused to believe that a regiment of their elite soldiers had been stopped by a single American platoon. Surely a whole American regiment must still be in the woods around Lanzerath. The commanding officer of the 9th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment refused to advance any further until daylight the next morning when it was safer. Angry at the holdup caused by the I&R platoon, the commanding officer of Kampfgruppe Peiper, Joachim Pieper himself, arrived and asked if the commanding officer had sent any patrols to see if there were more Americans in the woods. The commanding officer replied that he had not. Peiper then ordered the paratroopers to accompany his tanks forward. It was now 4:30 am.

The I&R platoon had held up the German advance for almost an entire day. This gave the Americans time for the 30th Infantry Division to join up with the 3rd Armored Division and the paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division to stop Kampfgruppe Peiper outside La Gleize a few days later. Peiper had only advanced 60 miles from his starting point before he was forced to retreat. Out of Piper’s nearly 5,000, men only 770 German soldiers would return to German lines on Christmas Day. Hitler’s dream of defeating the Allies in the West was over.

The men of the I&R platoon spent the rest of the war as POWs and were liberated four months later by American troops.

Though they did not know it at the time, Lyle Bouck and the other members of the I&R platoon had made a considerable contribution to the German Army’s defeat. As Bouck’s commanding officer, Major Robert Kriz, later wrote, “This small group of Americans had molded together to do something that they did not care to do, under the leadership of Lt. Bouck, (and) in giving of themselves gave a vast number of American troops a little more time to change positions, retrench, fight and hold to fight again another day.”

Historian John Della-Guistina writes that without the “heroic stand” by the I&R platoon, the Germans would have been able to “drive to the Meuse River” and capture Antwerp. Historian Alex Kershaw noted, “Had they not stood and held the Germans and halted the attack, or rather postponed it for a crucial 24 hours, the Battle of the Bulge would have been a great German victory.”

The exploits of the I&R platoon and the artillery observers were largely forgotten until columnist Jack Anderson wrote about them in Parade magazine in 1977. The U.S. Army formally recognized the valor of the I&R platoon in 1980, fully 35 years after the battle. Five members of the platoon were awarded the Silver Star, nine members were awarded the Bronze Star with a “V” for valor pin, and four members, including Lt. Lyle Bouck, were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. This made the I&R platoon the most decorated platoon in the U.S. Army for a single action during World War II.

In January 1981, President Jimmy Carter awarded the I&R platoon a Presidential Unit Citation. It reads in part, “Although greatly outnumbered, through numerous feats of valor and an aggressive and deceptive defense of their position, the platoon inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy spearhead of the attacking German forces. Their valorous action provided crucial time for other American forces to prepare to defend against the massive German offensive. The extraordinary gallantry, determination and esprit de corps of the Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon in close combat against a numerically superior enemy force are in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Army.”

After the article in Parade was published, the widow of William Tsakanikas, who died in 1977, was invited by New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner to throw out the first pitch of the home opener of the team’s season. The remaining members of the I&R platoon were also invited to line up behind home plate.

The Yankees’ announcer said, “In December 1944, eighteen brave Americans of the 99th Army Division halted a vast column of German tanks, paratroopers and SS troops in a fierce 18-hour battle … in the Belgian village of Lanzerath. These eighteen … thus blunted a massive surprise Nazi attack that could have changed the entire outcome of the Battle of the Bulge. On this opening day, the New York Yankees are remembering the survivors of Lanzerath, and hope they will not be forgotten by the country they so bravely defended.”

The I&R platoon received a standing ovation from the 52,000 people in attendance.

Brent Dyck is a history teacher in Bradford, Ontario, and is a frequent contributor to WWII History.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments