By Carole Butcher

One of the most enduring images of the Middle Ages is the tournament, with its knights in shining armor, heraldic devices on shields, fair damsels watching from the stands, and brightly colored banners flying in the breeze. At their onset, such tournaments served as a useful training tool for heavy cavalry. But by the Tudor Age, they had evolved into public events held for the purpose of displaying wealth and demonstrating power, an idealized form of combat that had little to do with true warfare.

The tournaments were fought by well-trained, nobly born knights. In France, they were known as chevaliers. In Italy, they were called cavalieres. In Spain they were caballeros, and in Germany they were Ritters, from the word meaning “to ride.” In each case, the name for the knight came from the native word for “horse.” The knightly code of chivalry itself derived from the French word cheval, for “horse.” From the very beginning, the knight was closely identified with his horse and inextricably bound to it. Dom Duarte, the king of Portugal, wrote in the 15th century, “Always to have good horses, to know them well and how to take care of them is worth more than knowing any other art imperfectly.”

Geoffroi de Charny gave a detailed description of a knighting ceremony that underlined the importance of the bond between the knight and his horse. While a young man knelt before his liege lord in the knighting ceremony, the lord handed a pair of gilded spurs to two knights. These knights then fastened the spurs to the feet of their new colleague. When the young man was dubbed on the shoulders with the flat of a sword and told to stand before all as a true knight, he was said to have “won his spurs.” The knighting ceremony was solemn and filled with symbolism, and the spurs were an important aspect of this symbolism. According to 13th-century knight Ramon Lull, “The spurs are given to a knight to signify diligence and swiftness. For likewise as with the spurs does he prick his horse causing it to hasten to rein, right so does diligence hasten the knight to do his duty.”

Breeding and training warhorses was an expensive undertaking. From the time of classical Greece and Imperial Rome, the mounted warrior came from the upper strata of society. The aristocratic classes of hippeus in Greece and equites in Rome drew their names from the words for “horse.” Because of the expense involved for armor, weapons, and well-trained warhorses, knights usually came from the land-owning class. As a rule, a knight was the son of a knight. While knighthood was not guaranteed for the child of a knight, it was nearly impossible for a child without chivalric connections to become a knight.

Renowned medieval knights such as Ramon Lull and Geoffroi de Charny charted a logical progression that would lead to a successful career as a knight. Prepared from childhood for a knightly vocation, young men trained in the martial arts and chivalry required of a knight. The youngest boys played with wooden swords. Older boys became familiar with armor, weapons, and the handling of horses by assisting knights. When in their early teens, aspiring knights began to wear armor and learn to ride a horse while handling lance, sword, and shield. This included engaging in games such as the quintain and jousting at rings. Jousts and tournaments were the next step that would lead to real combat. And it was in real combat that the true glory of knighthood was to be won, with the greatest honor reserved for those who took up the Cross and went on crusade.

Matthew Paris, a monk who wrote in the 13th century, called tournaments “a bloody sport indeed.” And such they were, particularly in their earliest form. Injury and death were risks for both the knight and his horse. A German chronicler recorded in 1241 that a staggering 80 knights and squires were killed in a tournament. In his first tournament, Robert of Clermont, brother of the king of France, suffered severe head injuries that left him permanently impaired. Since chroniclers routinely reported only the noblest and most famous casualties, it is quite likely that the true casualty list of any tournament was much longer.

It is difficult to determine the origin of the tournament. The earliest written mention comes in a chronicle of 1066 from the abbey of St. Martin at Tours, France, that describes the death of a knight in a tournament. It is probable that tournaments originated on the European continent. Gerald of Wales referred to “tournaments of the French sort.” Matthew Paris called tournaments “conflictus gallicus” and “batailles francaises.” William of Newburgh, who wrote in 1197, asserted that the first tournaments in England were held in the mid-12th century.

The early tournament consisted of the melee, in which teams of knights faced off against each other in mock battle. The marshal in charge of the tournament divided the knights into teams, often on geographical grounds but with an effort to keep the teams fairly even in number. Some knights formed themselves into teams, such as one led by the renowned English knight, William Marshal, and they traveled the tourney circuit together.

The team system in and of itself often became a cause for serious conflict. In 1251, the English team at Rochester held a grudge against a team of foreigners over the results of a previous tournament. The melee developed into a full-scale battle, with the English squires finally chasing the visiting team into the village and beating them with staves. Two years later, the Earl of Gloucester took his team to the Continent for a tournament and received such rough treatment there that they required medical attention before they could return to England.

The knights involved in a melee used the same weapons, armor, and horses that they used for war. There were no blunted weapons, and mock combat could result in real fatalities. In 1273, a tournament held near Chalons turned deadly when the Duke of Burgundy tried to pull King Edward I off his horse. Considering this to be unchivalrous, Edward lost his temper and galloped away with the duke still clinging to him and dragging the ground. Foot soldiers of both sides then entered the melee, shooting crossbow bolts at one another. The tournament became known as the Little Battle of Chalons, and both participants and spectators were killed in the fighting.

A melee could range over several square miles, with designated areas set aside for knights to go and rest themselves and their mounts before returning to the fray. Melees often started early in the day and lasted until dark. It was a golden opportunity for novice knights to learn how to handle their horses and weapons under combat conditions and to develop the necessary stamina. Since the melee was a team sport, knights learned how to function together as a unit. This was particularly useful since, just as in real warfare, knights might find themselves fighting shoulder to shoulder with complete strangers and they might have to learn in short order how to function together as a cohesive unit.

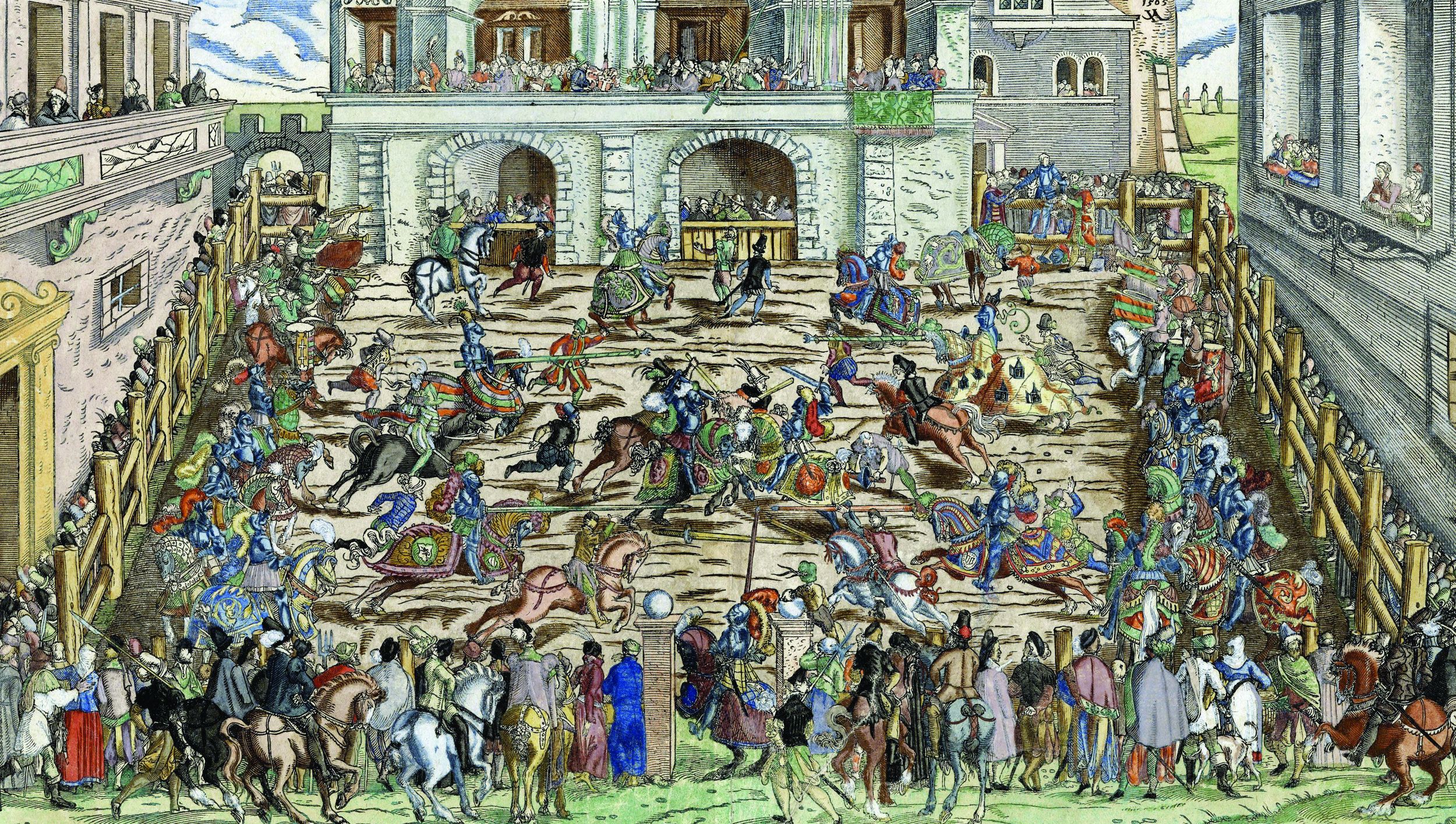

In the early form of tournament, there were virtually no rules in place for the protection of man or beast. They were violent free-for-alls, with little to distinguish them from the actual battlefield. Illuminated manuscripts give a glimpse into the chaos of a melee. The 14th-century manuscript The Romance of Guiron le Courtois provides a vivid depiction of just such a tournament, showing numerous knights in a confusing melee battling each other with lances. Other knights have been knocked from their horses, and in some cases their horses have fallen on them. All the while, admiring ladies watch from the stands.

Rene, Duke of Anjou and King of Jerusalem and Sicily, used illustrations of a melee in his manual on tournament fighting. In the first image, two large groups of knights face off against each other with the marshal separating them. This is the moment before mayhem breaks loose. Knights are crowded closely together, with each team consisting of four rows. Heraldic banners identify some of the well-known knights. A double barrier of two wooden fences separates the participants from the spectators. In the second image, knights armed with swords and accompanied by foot soldiers engage in a melee. Some of the knights have crashed through the wooden barrier and continued their fighting outside the list. Admiring ladies observe the contest from raised stands shaded from the sun.

The Catholic Church consistently opposed tournaments and attempted to ban them on numerous occasions on the grounds that they encouraged such vices as pride, anger, and lust as well as the tendency to cause public disorder. Tournaments were denounced from the pulpit, the clergy even citing the trampling of harvests as the knights charged each other and the high taxes imposed on peasants so that the knights could afford to participate. There was also the possibility of committing murder during the course of a tournament, since in the violence of the ostensibly friendly competition it was easy to pursue personal feuds. The gluttony and debauchery of the feasts that followed the spectacle were also offensive to the Church. An early 14th-century illumination depicts a melee in which knights are using sharpened swords. Devils hover over the altercation, ready to snatch the unfortunate soul of any knight killed during the melee.

Despite religious reservations, the tournament remained a popular pastime for participants and spectators alike. Banning tournaments proved to be impossible. William of Newburgh observed, “Knights were keen to acquire military fame and the favour of kings so they treated the Church’s prohibitions with contempt.” Pope Celestine III’s edict prohibiting the holding of tournaments was virtually ignored. Even the threat of excommunication or withholding church burial for those killed in tournaments was not enough to discourage knights from testing their skill and bravery on the field.

Richard I disregarded Celestine’s edict entirely and immediately granted licenses to hold tournaments. Recognizing the value of the tournament as a training tool, the king licensed five locations as official tournament sites. According to William of Newburgh, “The famous king Richard, observing that the extra training of the French knights made them more fearsome in war, decided that English knights should be able to learn from tourneying the art and customs of real war so that the French would no longer be able to insult them as crude and lacking in skill.”

Spiritual leaders were not the only ones who sought to ban tournaments. Secular leaders, too, had grounds for objections. The Church was concerned for the eternal soul of the knight, while the monarch was far more concerned with the knight’s body and his ability to answer the call to war. Knights were all too often killed or injured on the tournament circuit. In addition, knights who carried grudges against each other were known to carry the fighting beyond the bounds of the tournament field. Matthew Paris wrote in his Chronicles of several instances when King Henry III of England attempted to enforce a ban on tournaments, including one scheduled tournament that was to pit the Earl of Gloucester against Guy, son of the Earl of La Marche, in 1247. “The king,” wrote Paris, “who favored his brother Guy and his other Poitevin followers more than his natural English subjects, was very much afraid that, if the tournament took place, his brother and his supporters would be cut to pieces. So he strictly prohibited the tournament on penalty of disinheritance.”

This was not the only instance of a king prohibiting a tournament. Another incident also involved the Earl of Gloucester. The king had publicly granted permission to the earl to hold a tournament. The announced intent of the tournament was “so that William [the king’s half brother] and his fellow novices could gain experience in the arts of chivalry.” Once again, the English knights would be pitted against the king’s Poitevin supporters. “But because it was feared that the arrogant boasting of these people and other foreigners might cause quarrelling and fighting, and that bloody swords might strike after the spears had been broken, the lord king forbade the tournament.” The threatened penalty was royal disinheritance.

In the 13th century, Ramon Lull wrote his Book of Knighthood and Chivalry as an instruction manual on what it meant to be a knight. Lull’s handbook is a clear representation of the chivalric code. In discussing what they must do to maintain themselves, Lull urged knights to “undertake such sports as to make themselves strong in prowess, yet not forget their duties.” He admonished them “to hunt harts [deer], bears, and other wild beasts, for in doing these things the knights exercise themselves to arms and thus maintain the order of knighthood.” In particular, he noted that “knights ought to take coursers [warhorses] to joust and go to tourneys.”

While the tournament was a way for the novice to gain experience in warfare, by the 13th-century knights began to realize that there was the potential for substantial profit on the tourney circuit. William Marshal, perhaps the greatest English knight to take the field, made his fortune in just such a manner. A victorious knight was given a prize at the end of the tournament, but the real profit was to be made in ransom. The horse and armor of a defeated knight immediately became the property of the knight who had bested him. There was a substantial cost involved for the loser to regain his goods. While an advantageous marriage didn’t hurt Marshal’s finances, he made his real fortune—and his reputation—on the tournament circuit. In his very first tournament he defeated four knights and shared a defeat with another, leaving the field with a considerable amount of booty for one day’s work.

Rules for the tournament began to appear in the 13th century and gradually became consistent. Participants who broke the rules were not only in danger of losing their horse and armor, but were threatened with imprisonment or disinheritance as well. England’s Edward I drew up a formal rule book, the Statuta Armorum, in 1292. This was the first time that sanctioned tournaments required the use of “rebated” weapons—swords and lances that had not been sharpened and had blunt tips. There were also restrictions on the number of men who could accompany a knight, and those men had to be unarmed.

A knight’s squires and men-at-arms were required to wear his colors so that they could be easily identified in the event they engaged in disorderly conduct outside of the tournament field. The field itself became more defined. Rather than ranging across the countryside, the tournament was confined to a definite space called the list. The list was surrounded by wooden walls to keep spectators from harm. Contests between individual knights became more common. It was also at this time that a blunted tip for the lance came into use. Called a “coronel,” it was a metal tip with three blunt prongs that spread out the force of the blow and prevented penetration of an opponent’s armor. It was used to preclude serious injury to an opponent or his horse.

Charny wrote A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry in the 14th century as a detailed treatise on the rights and responsibilities of knighthood. He included a broad range of topics, from the responsibilities of a knight to instructions on how a lady should behave when she saw her knight honored by others. Tournaments, naturally, were a major topic in this discussion. Charny valued the knight who demonstrated his prowess in combat more highly than one who only fought in tournaments, believing that the “truest and most perfect form” of the practice of arms was to be found on the battlefield. But notwithstanding the high esteem in which he held the knight seasoned on the battlefield, Charny also had great respect for the tournament knight. He wrote of tournaments: “They earn men praise and esteem for they require a great deal of wealth, equipment and expenditure, physical hardship, crushing and wounding, and sometimes danger of death.” He went on to note that tournaments required “physical strength, skill, and agility.” He recognized tournaments as the logical starting point for a man-at-arms who was striving to become a knight.

The tourney circuit was a valuable training ground for young knights, but experience was gained at a cost—both physical and financial—and it was not an easy road. A famous anecdote about William Marshal illustrates the hazards faced by a knight on the circuit. After one tournament, the herald sought out Marshal to present him with the prize. He found Marshal at a blacksmith shop, head on an anvil while the blacksmith hammered Marshal’s helmet back into shape in order to remove it from the knight’s head. Matthew Paris also described the dangers of the tourney for William of Valence, half brother of England’s King Henry III, when the young man participated in a tournament as a novice. William’s skill apparently did not measure up to his enthusiasm, and his royal connections in no way exempted him from rough treatment. “But his tender age and imperfect strength not allowing him to resist the impetus of hardened and warlike knights,” wrote Paris, “he was prostrated and, as an initiation to knighthood, thoroughly beaten.”

But while acknowledging that there was a financial burden and physical danger involved in pursuing the chivalric arts, knights who wrote about their experiences invariably reinforced the idea that knighthood was well worth the cost: “While the cowards have a great desire to live and a great fear of dying,” wrote one knight, “it is quite the contrary for the men of worth who do not mind whether they live or die, provided that their life be good enough for them to die with honor. God is gracious toward those who find their life of such quality that death is honorable; for the said men of worth teach you that it is better to die than to live basely.”

Charny believed that a young man’s aspiration to become a knight was bred into him, and that such a determined young man would not let anyone dissuade him from attaining his goal. According to Charny, the desire to be a knight was embodied in the “nature and instinct” of a young man destined to be a knight, and that desire was demonstrated from an early age. Charny counseled such young men to learn all they could from experienced fighters, watching them and listening to them, and to bear arms themselves at the earliest opportunity.

Tournaments became much more formalized by the 14th century. The criee, or call to arms, preceded a tournament. Such an announcement laid out the terms of the tournament and typically gave the identity of the home team and the form of combat, specified whether only knights could participate or squires would also be welcome, and listed restrictions on weapons and prizes to be awarded. Sometimes penalties for breaking the rules were enumerated. At a tournament in London held in 1390, anyone who did not adhere to the rules “will neither carry away nor be given any manner of prize or degree. And whoever jousts with a lance without an appropriate coronel will lose their horse and their harness.”

Charny’s 14th-century treatise, Questions on the Joust and the Tourney, illustrates the main areas of concern regarding tournament rules. Most of the questions concerned horses. If no rules were announced, “Will he who knocks the other to the ground win the other’s horse?” If knights were jousting in an informal match, “Will he who knocked the other down win the horse?” And if the pickup fight involved squires instead of knights, would the winner take the loser’s horse? This treatise also demonstrated great concern with the question of responsibility for injuries to a horse. If a knight sponsored squires to joust with him and some of their horses were injured, was the knight obliged to pay compensation to the squires? If a knight’s horse was injured but he chose to finish the tourney on that mount, was the horse deemed to be injured enough for the knight to demand compensation? It is to be noted that Charny expressed no concerns about injuries to knights or squires. But a warhorse was a considerable investment. A comfortably well-off peasant family could expect to bring in three pounds over the course of a year, while an average warhorse cost five pounds, with some exceptional animals going for as much as 100 pounds.

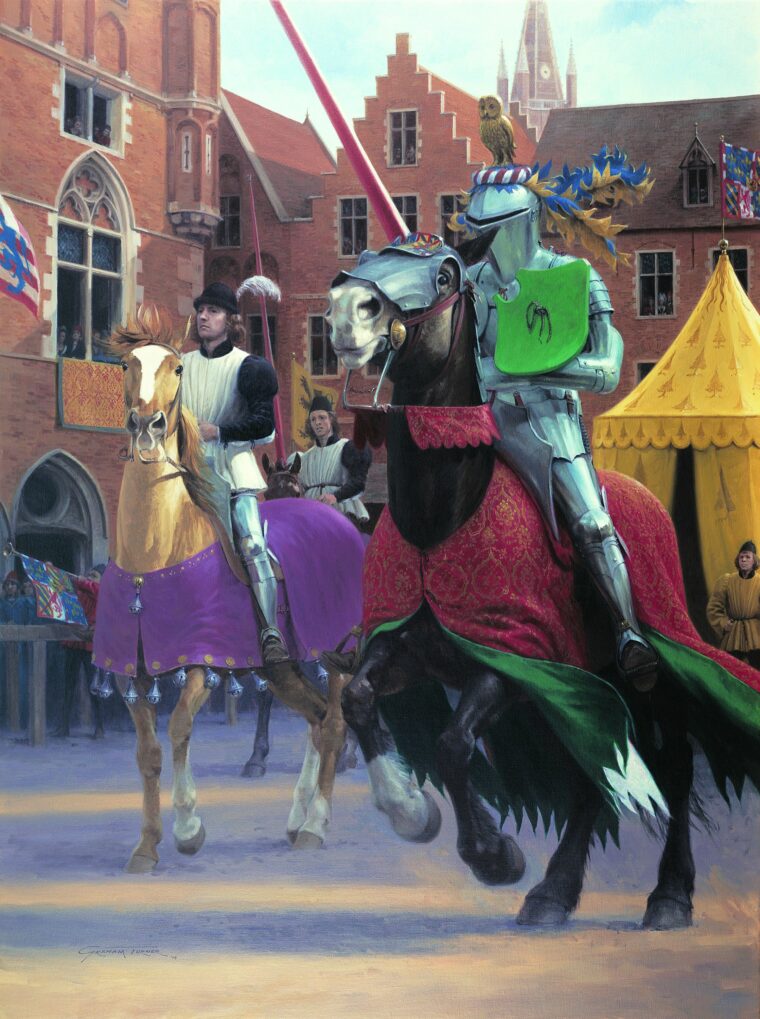

Developments in the 15th century indicated that the tournament was falling away from its original purpose as a training tool and was becoming nothing more than a game—albeit a dangerous one. Monarchs used tournaments as opportunities to show off their wealth and power. The melee became less popular and the joust replaced it as the highlighted contest at most tournaments. The “tilt” appeared in the 15th century. A barrier that ran the length of the list, the tilt was originally a rope with a piece of cloth thrown over it. Eventually it became a wooden barricade four to five feet tall. Each knight ran his course on his own side of the tilt. This ensured that, even at the point of impact, there would be no collision between the two horses. It was an innovation designed to improve the safety for both the knight and his mount.

Also at this time, armor was developed strictly for tournament fighting and differed significantly from armor used for war. The “frog-mouthed” helm was totally closed in the front, with a very narrow opening for sight and heavy padding. It was bolted to the body armor to keep it in place while jousting. The eye slot was placed in such a way that a knight held his head down in order to see his opponent during his run and, just prior to the moment of collision, lifted his head so that no lance or splinters could pierce the eye slot. This helm was in no way practical for warfare and was useful only for jousting. It also indicated the decreasing popularity of the melee, since it was useful only for the straight-line charge of the joust.

Popular myths to the contrary, a knight never had to be hoisted onto his horse with a pulley. A knight had to be agile in case he was unhorsed in combat. A knight who was unable to mount his horse in full armor without the use of stirrups would have been considered a very poor knight indeed. But during the 15th century, the weight of tournament armor increased in the interest of safety until it was not practical for combat. Tournament armor was designed for riding only. Some suits of armor were heavily reinforced only on the left side, where the knight would take a blow from his opponent’s lance, and it was no longer necessary for the tournament knight to carry a shield. The right side was fitted with a rest for the lance to keep it steady during the charge and the resulting collision.

Horse armor for the tournament was also improved during the 15th century, providing increased protection for the horse during the contest. A horse’s chest was protected by padding that flared out to protect the knight’s legs. The chamfron covering the horse’s face was often fitted with blinders to prevent the animal from being distracted from the straight run parallel to the tilt that was required in the joust. In some cases, a knight chose to ride with a “blind chamfron” that completely covered the horse’s eyes and was designed to prevent the horse from shying at the point of impact. Intricate articulated armor covered the horse’s neck, allowing the neck to move freely while also providing substantial protection.

As the weight of the armor increased, so did the size of the tournament horse. While warhorses were about the size of today’s standard riding horse, larger horses were bred and trained expressly for the tournament. Just as the tournament knight functioned as an individual rather than as a member of a cohesive combat unit, so too did his horse. A tournament horse was trained to run straight along the tilt, not veering at the moment of collision. A warhorse, by contrast, was trained to charge in a unit of heavy cavalry and was also trained to bite and kick at opponents during a battle.

In 1466, John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester, created rules that became standard practice for English jousts. The best jouster was one who unhorsed his opponent but, judging from period descriptions, this was very difficult and not all that usual. The most common winner was the fighter who broke the most lances. The breaking of a lance earned an attaint or point, with a break on the helm worth two breaks on the body.

The tournament in the 16th century became a pageant, with elaborate set pieces and costumes. A monarch might construct an entire forest in the list field, complete with animals and damsels in distress. Some tournaments portrayed the siege of a castle. Jousts were even held in the great hall of a castle at Lille, with horses shod with felt to prevent slipping on the marble floors. The tournament had always been a substantial expense for competing knights, but it now became increasingly costly to sponsor one. In 1511, Henry VIII spent 4,000 pounds to present a single tournament at Westminster. At the time, that was roughly twice the cost of building and equipping a warship. Nine years later, Henry met Francis I of France at the aptly named Field of the Cloth of Gold, where each monarch tried to outdo the other in sponsoring a lavish tournament. Extravagant costumes were covered in gold, hence the name of the gathering.

Heavier armor and safety precautions notwithstanding, the tournament remained a dangerous sport. In 1501, five participants were killed in a tournament in Rome. In 1524, Henry VIII was nearly killed in a tournament when the visor of his helm came open and he was hit in the face by splinters from a broken lance. In 1559, Henri II of France was less fortunate after he decided to take one more run at the end of a tournament. The Constable de Montgomeri shattered his lance on the king’s shield. In an accident eerily reminiscent of the one that had nearly killed Henry VIII, a splinter from the broken lance entered the king’s visor and fatally wounded him.

About this time, the tournament took yet another step away from combat training with the introduction of the bourdonass, a hollow lance designed to break instantly upon impact. Other contests made their way into the tournament, including the carrousel, which consisted of teams of knights using padded clubs to knock the crests off the helms of the other team. Other athletic contests were added, including archery, wrestling, and casting the bar, which was similar to the Scottish tossing of the caber.

But in spite of the fact that the tournament had evolved into a lavish pageant that had little to do with the skills required by a knight in combat, it remained an important component in the chivalric culture of the Middle Ages. The tournament still provided an opportunity to display the qualities most prized in a knight: prowess in combat, chivalry to opponents, courtesy to ladies, and generosity to underlings.

Another type of joust, while not used as training for warfare, required all the skill and ability of a knight in combat. This was the trial by combat, which was literally a life-or-death matter. It was possible for one man to challenge another in a duel to resolve a disagreement or redress a slight. The medieval chronicle Tales from Froissart includes the story of one such duel between James le Gris and John de Carogne. In 1386, while Carogne was away, le Gris came to his castle and raped his wife. Upon returning home and learning of the incident, Carogne told his wife, “I forgive you, but the squire shall die.” Le Gris denied the charge and Carogne took his case to the parliament.

Unable to come to a decision because it was the lady’s word against his, the parliament judged that the matter should be decided in the tilt-yard by a duel. It was life or death for the lady as well, since if her lord lost the bout, it would be assumed that she had lied and she would be burned at the stake. The two opponents fought with lances, then dismounted to fight with swords. Carogne was wounded, but he prevailed and killed le Gris—much to his wife’s relief. This was the last documented tournament as trial by combat.

While individual jousts during warfare were not common, they were not unknown. Perhaps the most famous occurred just prior to the Battle of Bannockburn. Robert the Bruce, who was labeled by none other than Edward I as the “finest knight in Christendom,” squared off against the English knight Sir Henry de Bohun in an impromptu joust. As the English prepared for their cavalry charge, Bohun caught sight of the Bruce. The English knight, attempting to finish the battle with one swift blow, couched his lance and spurred his great warhorse directly at the king of the Scots. Armed only with a battle-ax and mounted on a small Highland pony, the king waited patiently until Bohun was nearly upon him. Then, the Bruce sidestepped his opponent, stood in his stirrups, and neatly split Bohun’s skull with a single blow. Bohun was dead before he hit the ground.

The tournament never truly lost its popularity or its place in the public’s imagination, and as late as 1839 the Earl of Eglington attempted to revive the sport by organizing a tournament. The popular 2001 movie, A Knight’s Tale, starring the late Heath Ledger, portrayed knights on the tournament circuit as medieval sports heroes, and that may not have been far from the truth. Renaissance fairs remain popular today, with thousands of visitors attending events each year. While visitors enjoy the food, shopping, magicians, and troubadours, by far the most popular attraction is the joust. It should be noted, however, that such jousts are carefully choreographed, and lances are designed to shatter easily. The medieval tournament has embedded itself in the modern imagination, and it holds a permanent place in Western culture.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments