By Peter Suciu

World War II saw great advancements in firearms technology. Many nations that entered the conflict with bolt-action rifles ended the war with a variety of complex submachine guns and assault rifles. While owning operational models of these weapons today is often costly and difficult because of the paperwork required, a nonfiring version can make an impressive display for modern collectors.

In all 50 states, owning an automatic firearm can be a costly endeavor, and in many locations simply impossible. Obtaining the necessary permits can be time-consuming and typically requires numerous background checks. Anyone considering applying for such permits should check state and local laws before doing so. Some communities have bans in place, and even with the proper federal licenses, adding such weapons to a collection can be difficult or even illegal. Nevertheless, historical firearms from World War II have escalated in value in the last decade. Virtually all of the few operational, fully automatic weapons are in private collections and thus are sold from collector to collector.

Today, even common weapons like the German K-98 bolt-action rifle and the American M1 Garand have become extremely desirable with collectors, and prices for models with matching numbers in good condition can easily exceed $1,000. These firearms typically don’t require special paperwork or permits, but would-be collectors should consult local laws—New York City, for example, requires all long guns to be registered, and the M1 is on the list of banned weapons. San Francisco has essentially banned all firearms completely.

With full-automatic weapons, collecting is even more difficult. Firearms from WWII that typically require special permits and licenses, among them the infamous MP-40 submachine gun or the Thompson, are especially sought after these days and can fetch prices exceeding $10,000. Needless to say, most collectors cannot readily afford to met those prices. Fortunately, there is still hope for the collector who wants to own an impressive piece of World War II history but doesn’t want to mortgage his house to do so. One way is to buy a non-gun, a firearm created—or, more accurately, recreated—from real parts. These are built from parts kits. The assembled gun looks complete but is not a working firearm. Such pieces cannot fire or even chamber ammunition. The receiver, the portion of the gun that chambers and essentially operates the weapon, is replaced or cut, rendering the weapon inoperable and thus legal to own in many states.

The nonoperating weapons make great display items, either mounted on the wall or used with a mannequin as part of a uniform showcase. Nothing completes the setup of an United States Marine uniform display like a period Tommy Gun, or a late-war Waffen-SS setup like a German MP-44 assault rifle. “Non-guns are becoming very popular because registered machine guns are becoming extremely expensive and some states even forbid ownership,” says Nikki Whitsell, store manager of Allegheny Arsenal, one of several dealer firms that create nonoperational display items. Whitsell adds that non-guns are not restricted federally and are only restricted in a few states or cities. “With the non-guns you basically have about 80 to 90 percent of the real gun with a solid receiver; it cannot be fired, but it can be displayed. It looks like a real gun.”

Collectors should check with local laws before obtaining any of the non-guns. From a federal standpoint, a non-gun must meet certain criteria. This is especially important to note, because many sellers claim—erroneously—that their items are compliant with the National Firearms Act (NFA) and the guidelines of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF). In fact, the ATF has no classification for dummy or non-guns, except to say what is not a gun. The Gun Control Act of 1968 defines the term “firearm” to mean, in part, “any weapon (including a starter gun) which will or is designed to or may be readily converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive” or “the frame or receiver any such weapon.” Furthermore, the National Firearms Act specifies that a “machine gun” is “any weapon which shoots automatically more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger [and] the frame or receiver of any such weapon.”

The NFA also specifies acceptable methods for creating a proper non-gun. A machine gun receiver that has been properly destroyed may be used to assemble a “dummy gun” that is not subject to the controls of the National Firearms or Gun Control Acts. When sections of destroyed machine gun receivers are used to build a dummy gun and the severed sections are welded back together, the dummy gun receiver must be at least one inch shorter than the

original receiver. The bolt, if present, must be welded to the receiver in the closed position. The breech of the barrel must be welded closed and an obstruction welded into the barrel. Alternatively, a solid metal or plastic bar in the same shape and configuration as the original model maybe used as a “dummy receiver.”

The ATF further states that commercial glue or nonmetal materials not be used in any cutaway section of a cut receiver for the purpose of filling it in. This would be seen as essentially restoring the gun, and since many of these fillers offer the same tensile strength as metal, this could result in the gun being restored to a firing condition. Essentially, it is a matter of the receiver. If you a have a receiver that was not properly destroyed, you have a machine gun.

While this might seem fairly complex, the best advice is to purchase any non-guns from a specialized and reputable dealer, rather than from an individual at a militaria show or online, unless you are certain the item meets the aforementioned standards. You should check for local laws and be sure to ask any sellers if they are familiar with the National Firearms or Gun Control Acts. If they say no, then they can’t possibly claim to be compliant to ATF standards. In such cases, it is best to walk away from any potential transaction. “The code of federal regulations, like all laws, is subject to varying interpretation,” notes Matthew Siler of Siler Militaria. Unlike many other sellers of non-guns, Siler has actually sent examples of his receivers to the ATF’s Firearms Technology Branch in West Virginia for review. “After careful study of the law, it seemed that with careful engineering one could produce a realistic dummy gun without running afoul of the law.”

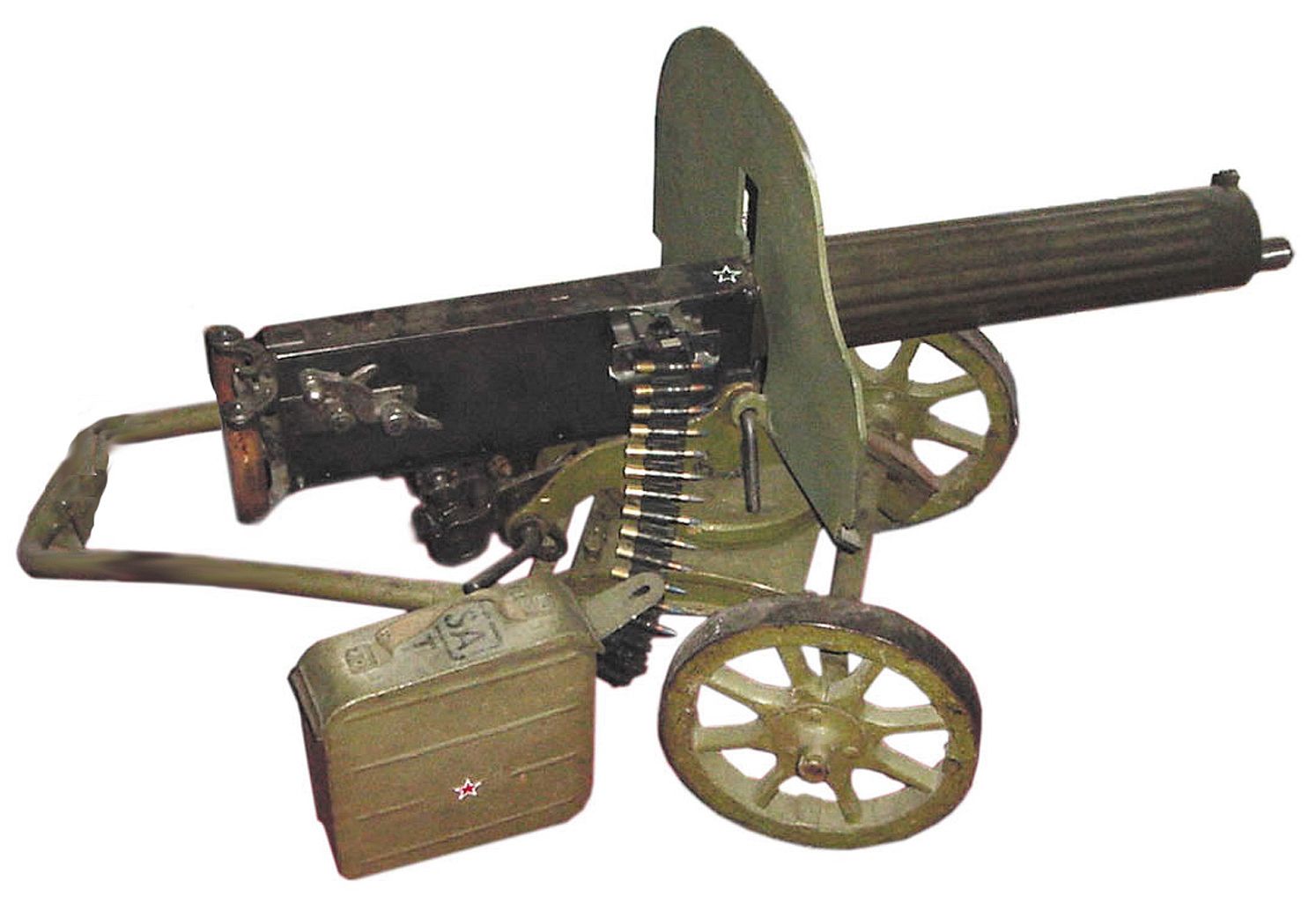

The other option for collectors is to buy a parts kit and assemble their own dummy gun. Of course, buyers should be sure to review all ATF guidelines and check with local law enforcement to make sure they are not inadvertently restoring a machine gun. To be sure they are in the clear, some collectors have even avoided anything too close to the actual parts. Advanced Russian and Soviet militaria collector Dr. Robert Clawson, emeritus professor of European Military Studies at Kent State University, says the numerous copies in his collection fill a void of otherwise unobtainable items. One Russian light machine gun even has a receiver that is nothing more than foam board painted flat black. Clawson says, “It doesn’t fool anyone who knows anything about firearms, but it looks great from about 10 feet.”

The downside to buying parts kits or non-firing guns is that, as of last year, a ban has been placed on the importation of parts kits. The items that are already in the country are the last of the so-called “new” ones that collectors will be seeing. Considering that these have been produced for about the last 20 years or so, they can be still be readily obtained, but like the live-firing K-98s and M1 Garands, nonfiring weapons are only going to increase in price.

While the parts ban will no doubt mean that the non-guns made from real parts will be harder to find, collectors looking for display items still have several options. The most common solution over the last 40 years has been to buy a nonfiring replica, or counterfeit, gun. The early models of classic World War II weapons were extremely popular, as they closely resembled the real deal and had moving parts. Made of metal, they even had the weight and feel of the real guns, but with plugged barrels that made chambering or firing the guns impossible.

Rumors still abound that some of the so-called counterfeits can be converted to fire live ammunition. Considering that they were made of lighter-gage metals, this seems dubious at best, and one is advised to never try using live ammunition with any of these copies. Most of the copies came from Japan, but less desirable copies are starting to appear from China and India. Beware of online auctions when buying these; the photos may often be of a real weapon, but the delivered goods are cheap-looking plastic copies.

The Marushin replicas from Japan were considered to be among the best nonfiring counterfeit guns, and as a result they have become much sought after as collectibles in their own right. Counterfeit MP-40s, or Tommy Guns, once sold for under $100, but now fetch $400 or more. The craftsmanship in some of the models was truly outstanding. Clawson explains that while today most of these counterfeits require an orange plug, the early ones looked very convincing. “Why buy replicas?” he asks. “For one thing, some of the real guns cannot be obtained legally or just don’t ever come on the market for budget-conscious buyers. If the idea is simply to display what they were like and not have a real lethal weapon, they do a job of substituting for the real thing if their quality is good enough.”

And for some firearms, a real one—even of the non-gun variety—is simply impossible to obtain. The ultra-rare German FG-42, the automatic rifle used by the German paratroopers in the latter half of World War II, is considered almost unattainable. Live versions, when they show up for sale, have fetched $30,000 or more. Because the Marushin counterfeit version was never produced in large numbers, these can cost around $1,500. For collectors looking to finish off a nice paratrooper display, such as one depicting the battle at Monte Cassino, the copies are considered essential.

In addition to the Marushin copies, which have declined in quality over the years, other versions of counterfeits have also begun to show up. Today, nonlethal versions of famous firearms are available in plastic varieties and can look quite convincing, but they won’t fool anyone up close. This doesn’t mean they are toys, and as with any replica firearm, care should be used in how and where they are displayed. Plastic ones can be made to appear even more realistc when used in your uniform or weapon display. If you have some skills with models, a little bit of paint can transform these into rather striking display pieces.

Many of these copies are actually made for sport. They can fire small yellow plastic balls for a game called Airsoft, which is similar to paintball. It is important to note that these are often classified as air guns, so again one should check with local laws. Many communities have banned the sale of air guns. However, combining the Airsoft game with traditional reenacting has been catching on, becoming yet another way to recreate history that doesn’t involve purchasing and maintaining blank-firing weapons.

One other alternative to the deactivated or realistic copies are those made of resin or similar solid-mass materials. These solid guns, which typically have no moving parts, are ideal for displays, in part because of their light weight and the fact that virtually no laws prohibit their ownership. As always, common sense should be applied, especially if you are using them in reenactments or other living-history events. They do look quite convincing, so caution should be taken when carrying the—even though they are made of a plastic-like material, they shouldn’t be considered toys. At a distance they look like the real thing, and hence are good for displays but not for kids to play with in the backyard.

“You can put these in your vehicle or carry them around at a reenactment and not worry about having a genuine gun being stolen or damaged,” says Kevin Kronlund of Army Cars USA, who sells a variety of the mock firearms. “What used to be a big-ticket item to complete a vehicle restoration project has now become a reasonably priced alternative.” Kronlund takes pride in making his guns look as realistic as possible, adding that his models are airbushed to give them a used look, and as a result no two guns are exactly the same. The materials are a combination of resin and fiberglass with metal reinforcement, so while you will still want to be careful in the field, these items can take a bit of light abuse.

Kronlund and other dealers offer a range of WWII weapons, including the M1 Garand, the MP-44 assault rifle, and the Thompson SMG, with both stick and drum magazine options. There are even .50-caliber machine-gun models, made with a steel rod down the length of the barrel to make them more rigid. Finding a real one, even in the non-firing configuration, for your jeep would probably be an expensive endeavor. Best of all, these resin guns don’t have to be cleaned and rain won’t damage them.

Clawson and other collectors agree that buying replicas comes down to how much one is willing to pay. Today, an MP-40 is still among the most sought-after non-gun, and a well-made one with good original parts around a convincing dummy receiver will easily cost more than $2,000. An exceptional piece could exceed the $3,000 mark, almost double the price these were fetching a few years ago. Even those old Marushin copies have gone up in value, with those from the 1970s being considered true classics by purists. These can be found at larger military shows and online, but be wary of online auctions or other Internet purchases. Plastic copies can typically be imported, but these are starting to fall into a legal gray area in some communities.

Collectors should not attempt to purchase or import any parts or non-guns. Most nations have different laws, and legal interpretations, that define a “non-gun.” In the United Kingdom, for example, the law has changed over time, and current deactivation rules require the receiver to be welded shut, and all guns must be certified at a proof house either in Birmingham or London to make sure they meet proper standards. For these and many other reasons, American collectors shouldn’t waste their money or time purchasing non-guns from other nations. In this post-9/11 atmosphere, even Canadian non-guns are best left in Canada.

There are plenty of reputable dealers stateside for non-guns and counterfeits. But as previously touched upon, check your local laws first. Once you’re certain you’re in the clear, a non-gun or copy displayed with a collection can make quite an impact. “They are fine display items,” stresses Clawson, who says that many of his guests have been impressed with his nearly dozen nonfiring Soviet weapons, including Russian visitors who had only heard of the famous PPSh-41, the gun that practically turned the tide of war on the Eastern Front during World War II, but had never have seen one up close. “They go away shaking their heads in delighted amazement,” he notes with pride.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments