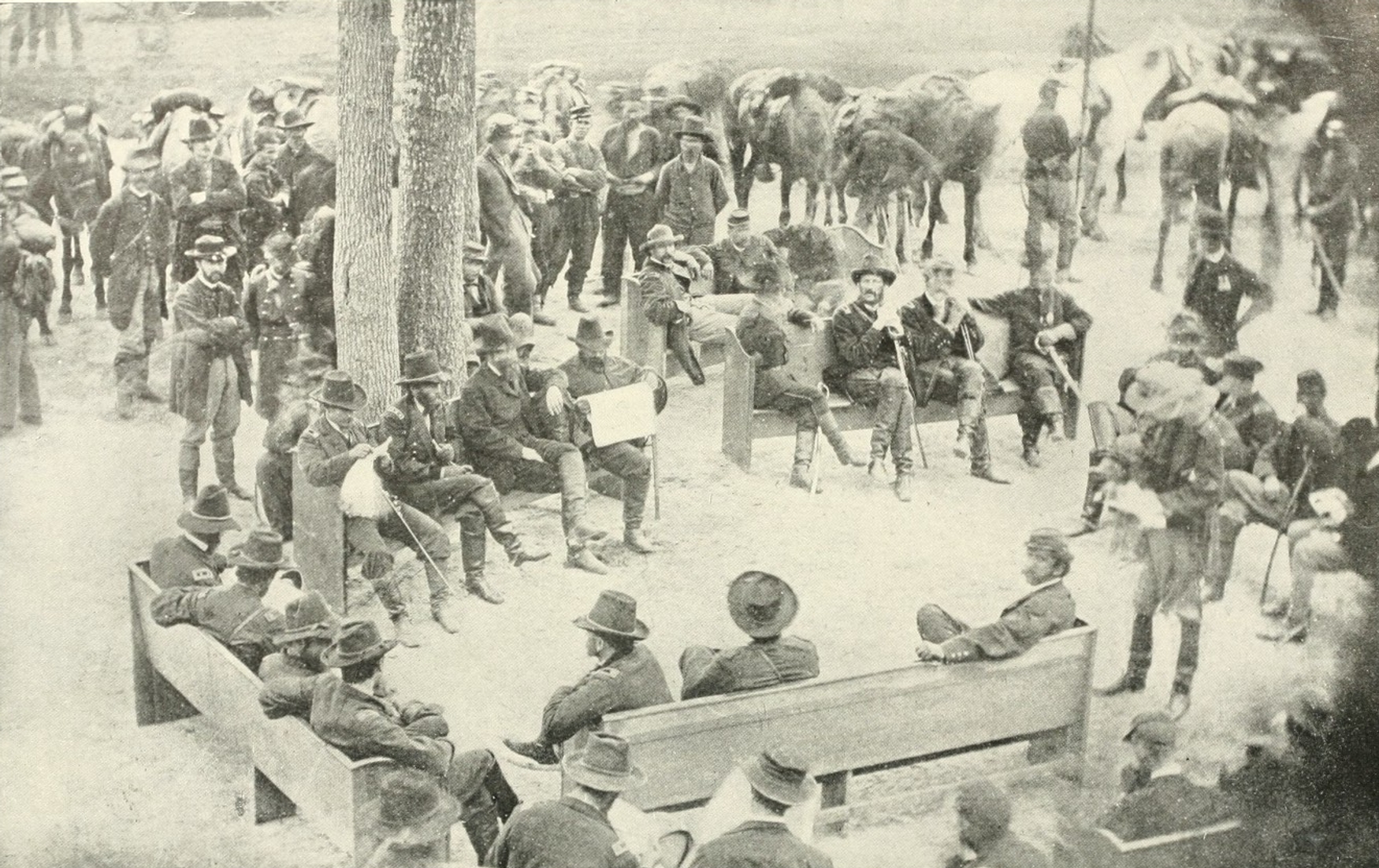

The dirt roads leading from Spotsylvania toward the North Anna River 20 miles to the south were choked with blue-uniformed Union troops and gray-clad Confederate troops on May 21, 1864. General Ulysses S. Grant’s Union army shadowed General Robert E. Lee’s army as it relinquished more Old

Dominion soil. Lee resigned himself to taking up a new position behind the North Anna River guarding the crucial railroad hub of Hanover Junction.

The heavy losses the Army of Northern Virginia had suffered in the preceding weeks were offset in part by the arrival of five brigades totaling 8,000 men called from points south and west to reinforce Lee’s army for yet another major showdown with the Army of the Potomac.

At first glance, the terrain along the North Anna seemed to favor the Union army because the north bank was higher in elevation than the south bank. This would give the numerous Union batteries the ability to sweep the ground along the south bank.

Both Grant and Lee expected a major battle to unfold on the North Anna line. Each had his idea of how he would prevail in the encounter. For his part, Grant planned to fix Lee’s army in place by simultaneously striking both of its flanks. He would then use his superior numbers to gain Lee’s rear. Lee intended to make a bold counterattack that would isolate and destroy part of the Union army.

Lee, already familiar with the terrain from the Seven Days Battles, took up a strong position once he arrived. “At the North Anna River, by an imaginative use of the terrain, [Lee] turned a crisis into a tactical stroke of genius,” wrote historian Clifford Dowdey. “Necessity and the terrain combined to form Lee’s spontaneous plan.”

Lee adapted the positions of his three corps to the location of the fords and bridges. The resulting lines and earthworks formed what was for all intents and purposes “a triangular fort,” wrote Dowdey.” The point of the triangle was at the river to block the Ox Ford crossing, and the oblique sides served as bastions against a land attack by Federal forces that managed to cross the North Anna River to assail the Confederate flanks.

Lee intended to use Hill’s corps to hold his left flank against Union troops crossing at Jericho’s Ford, while Anderson’s and Ewell’s corps would wait for an opportunity to counterattack the Union troops who crossed at Chesterfield Bridge to assail his right flank. Since the Confederates enjoyed the advantage of interior lines, Lee could easily shift troops from one wing to the other as necessary.

Major General Gouverneur Warren’s V Corps crossed the North Anna to probe the Confederate left wing, while Maj. Gen. Winfield Hancock’s II Corps crossed the river to do the same to the Confederate right wing.

Even the best laid plans, though, cannot always hold up owing to unforseen developments. Lee and his corps commanders did not function at their usual high capacity at North Anna. Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill did not perform his duties as expected, Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s physical condition continued to deteriorate, and Lee suffered from a debilitating intestinal problem. Lee unfortunately had to let the opportunity to possibly destroy a Union corps slip by.

Grant recalled his forward units from the south bank and on May 27 his army marched by its left flank toward Richmond. Lee reiterated to his top commanders the need to strike a blow against Grant’s army.

“We must destroy this army of Grant’s before he gets to the James River,” he told Maj. Gen. Jubal Early. “If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.”

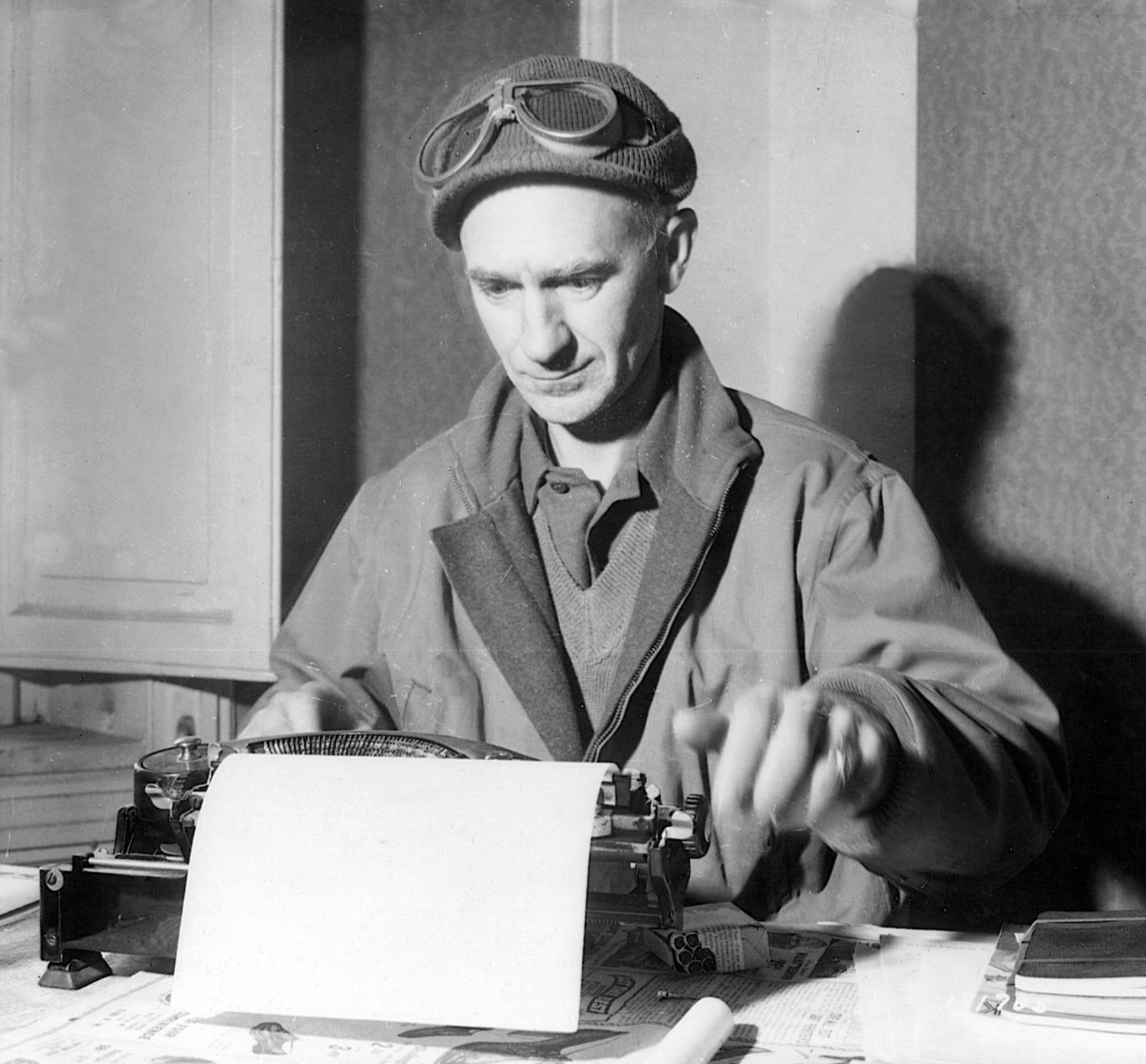

—William E. Welsh

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments