By Lt. Col. Harold E. Raugh, Jr., Ph.D., U.S. Army (Ret.)

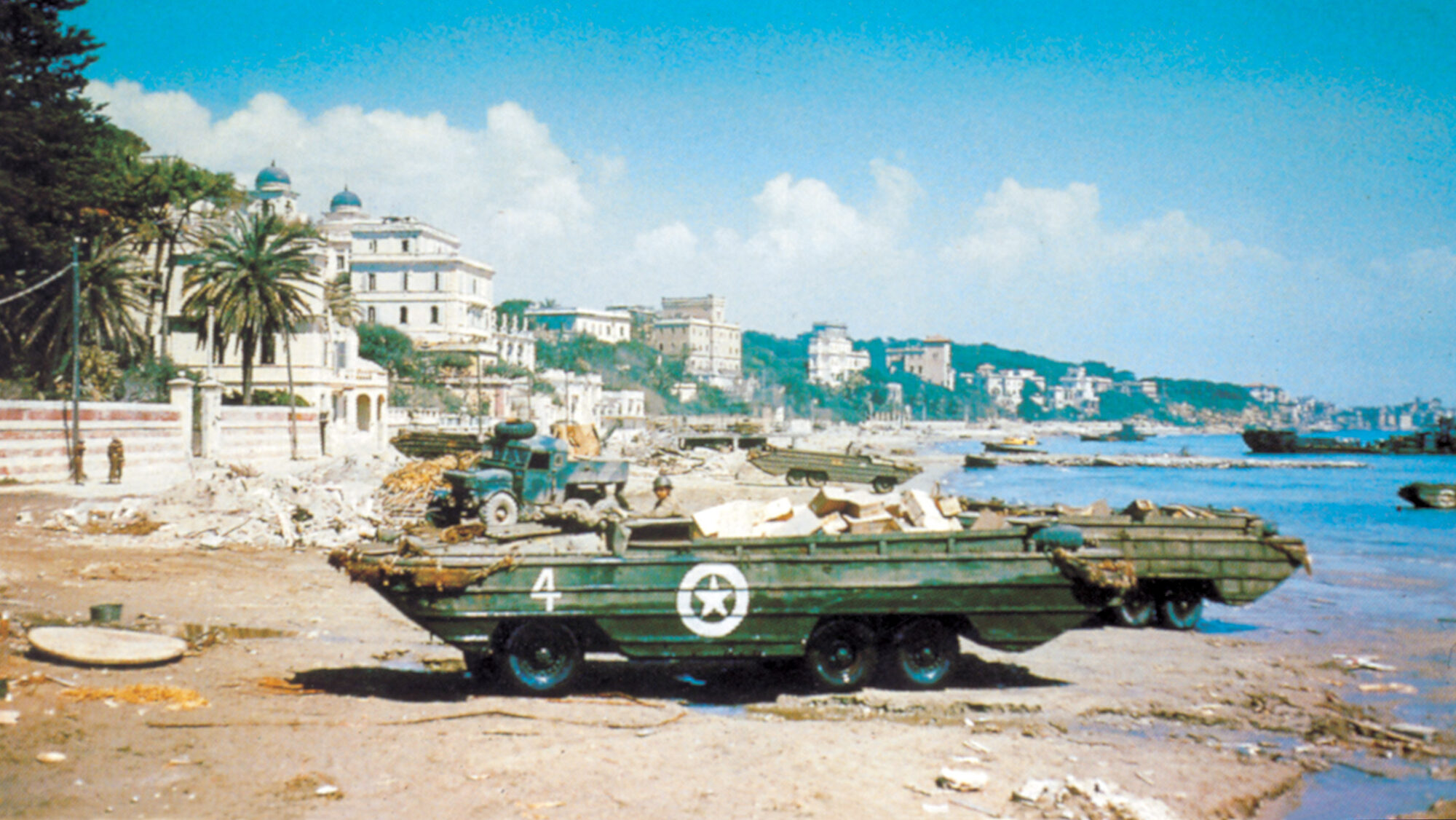

The World War II campaign in Italy, fought in rugged terrain that favored the German defender, inhibited maneuver, and restricted resupply efforts, had ground to a standstill by the end of 1943. In order to break the stalemate, the Allies conducted an amphibious operation at Anzio behind enemy lines, hoping to surprise the Germans and beat them in a race to Rome. If the

Anzio operation had succeeded, it would have been termed “brilliant”; the stark failure of the battle, however, strongly suggests major shortcomings in conception, planning, and execution.

Eminent military historian Martin Blumenson originally wrote Anzio: The Gamble That Failed (Cooper Square Press, NY, 2001, 212 pp., maps, index, $17.95 softcover) in 1963 in an attempt to dissect and assess this ill-fated venture. The author shows convincingly that the operation and its outcome were a manifestation of the disagreement between Great Britain and the United States over strategy, specifically the timing and location of the main assault on the European continent.

Eminent military historian Martin Blumenson originally wrote Anzio: The Gamble That Failed (Cooper Square Press, NY, 2001, 212 pp., maps, index, $17.95 softcover) in 1963 in an attempt to dissect and assess this ill-fated venture. The author shows convincingly that the operation and its outcome were a manifestation of the disagreement between Great Britain and the United States over strategy, specifically the timing and location of the main assault on the European continent.

The British, concerned about an empire that included Gibraltar, Malta, Egypt, and oilfields in the Middle East and the Persian Gulf, were anxious to retain control of the Mediterranean, especially as the lifeline to India. The Americans, on the other hand, with no imperial baggage and shouldering most of the war effort in the Pacific, wanted a quick, decisive blow against the Axis, preferably by attacking across the English Channel and through northwest Europe into Germany. These divergent issues—plus logistics, manpower, and other factors— and the strength of Anglo-American desire to divert German troops from the Eastern Front conspired in the decision to strike at Anzio.

Early in the morning of January 22, 1944—two days after the U.S. 36th Infantry Division’s disastrous attempt to cross the Rapido River—the amphibious assault landings at Anzio began. The force consisted of Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas’s VI Corps, which comprised the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, two U.S. parachute infantry regiments, elements of the U.S. 1st Armored and 45th Infantry Divisions, the U.S. Ranger Force of three battalions, the British 1st Division, and a British Special Service Brigade of two commando battalions.

Lucas and his immediate superior, Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark, Fifth Army Commander, both expected to encounter stiff German resistance at the Anzio beachhead. Amazingly, the Germans were taken by surprise, and rather than immediately seizing the nearby open Alban Hills—beyond which Rome lay virtually undefended—Lucas slowly secured the beachhead and built up his logistical base. Clark, visiting the beachhead on January 22, concurred with Lucas’s actions (although the latter was relieved a month later). As a result, they missed a tremendous opportunity to seize Rome with minimal casualties and expenditure of resources.

One German general later remarked, “On January 22 and even the following day, an enterprising formation of enemy [Allied] troops … could have penetrated into the city of Rome itself without having to overcome any serious opposition…. But the landed enemy forces lost time and hesitated.” The Germans were able to respond quickly, soon encircling the Allied force. Although the Allies attempted to break out of the beachhead on January 30, they were thwarted by the Germans. From the initial landings on January 22 until May 25, the beachhead was never expanded more than 12 miles inland, and all of it was vulnerable to German shelling. It was a veritable hell on earth, costing the Allies 7,000 soldiers killed, 36,000 wounded or missing in action, and 44,000 hospitalized.

The author’s detailed and thorough knowledge of Allied and Axis sources of information permits him to “see the battlefield,” ascertain the courses of action available to and the intent of the various protagonists, and explain causes and effects. The result is a superb, omniscient narrative. When originally published in 1963, this study had, other than a solitary explanatory footnote, no endnotes or references. The page-and-a-quarter narrative on sources is woefully inadequate for the reader to use to verify factual information and guide further research. These shortcomings remain in this exact reprint of the original edition.

Blumenson’s well-written, insightful, and fast-paced Anzio: The Gamble That Failed is an anatomy of a military disaster. Readers will be rewarded with a deeper understanding of this saga of an ill-conceived operation and notorious lost opportunities, tempered with the perseverance and intrepidity of Allied soldiers.

Recent and Recommended

Recent and Recommended

Moonless Night: The World War II Escape Epic, by B.A. James, Pen & Sword Books, Leo Cooper, Barnsley, S. Yorks., UK, 2001, 224 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, index, $36.95 hardcover.

“We had passed through a nightmare experience of what can happen, in any country, when the forces of totalitarianism prevail,” observed Royal Air Force Pilot Officer B.A. “Jimmy” James at the end of World War II. To be sure, James’s World War II experience as a prisoner of war beginning in June 1940 was a veritable nightmare from which he made no less than a remarkable 12 escape attempts, including the “Great Escape” of March 1944. Moonless Night, James’s recollections of his wartime captivity and escape attempts, published originally in 1983, is an enthralling account of courage, determination, and innovation.

Shot down while flying a Wellington on a bombing mission over the Netherlands in June 1940, James parachuted to earth—and German captivity. He was first incarcerated at Stalag Luft I north of Berlin, and he chronicles the daily routine, diet, and activities of the officer POW. The worst enemies of the POWs, in addition to the Germans, hunger, cold, and fear, were uncertainty and monotony. To alleviate boredom and as a means of doing one’s duty to extend the war effort, POWs frequently participated in escape activities. James became an energetic and enthusiastic tunneler. The officers’ compound at Stalag Luft I was honeycombed with some 45 tunnels in April 1942, when he and his comrades were moved to a new camp, Stalag Luft III, at Sagan, Silesia.

The North Compound of Stalag Luft III held over 1,200 POWs, about half of whom were actively involved in a superbly planned and organized escape operation. All resources were concentrated on digging three tunnels, “Tom,” “Dick,” and “Harry.” “Tom” was eventually discovered by the Germans, and “Dick” discontinued, but “Harry” was dug at a depth of over 25 feet, an amazing length of 365 feet, displacing some 130 tons of sand.

On the moonless night of March 24, 1944, the mass breakout of the unprecedented “Great Escape”—immortalized by the movie of the same name starring Steve McQueen—took place. James was the 39th out of 76 men to clear the tunnel to actually escape. Of the 76 escapees, only three made it home. Fifteen were returned to Stalag Luft III, eight (including James) were incarcerated in concentration camps, and 50, chosen at random, were executed. The contribution of the “Great Escape” was truly significant, out of all proportion to the number of escapees, as it “caused the Germans to divert about five million of their population, directly and indirectly, in the search for the escapers [for] about three weeks.”

After Gestapo questioning, James was sent to the “inescapable” Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. In the shadow of the camp gallows, he and a small group of POWs dug another tunnel and escaped in September 1944. Free for two weeks, James expected to be shot when recaptured, but was sent to the notorious Zellenbau (Cell Block) at Sachsenhausen, where “few incarcerated therein ever lived to tell their friends about it, and certainly not those who had escaped from the all powerful SS.”

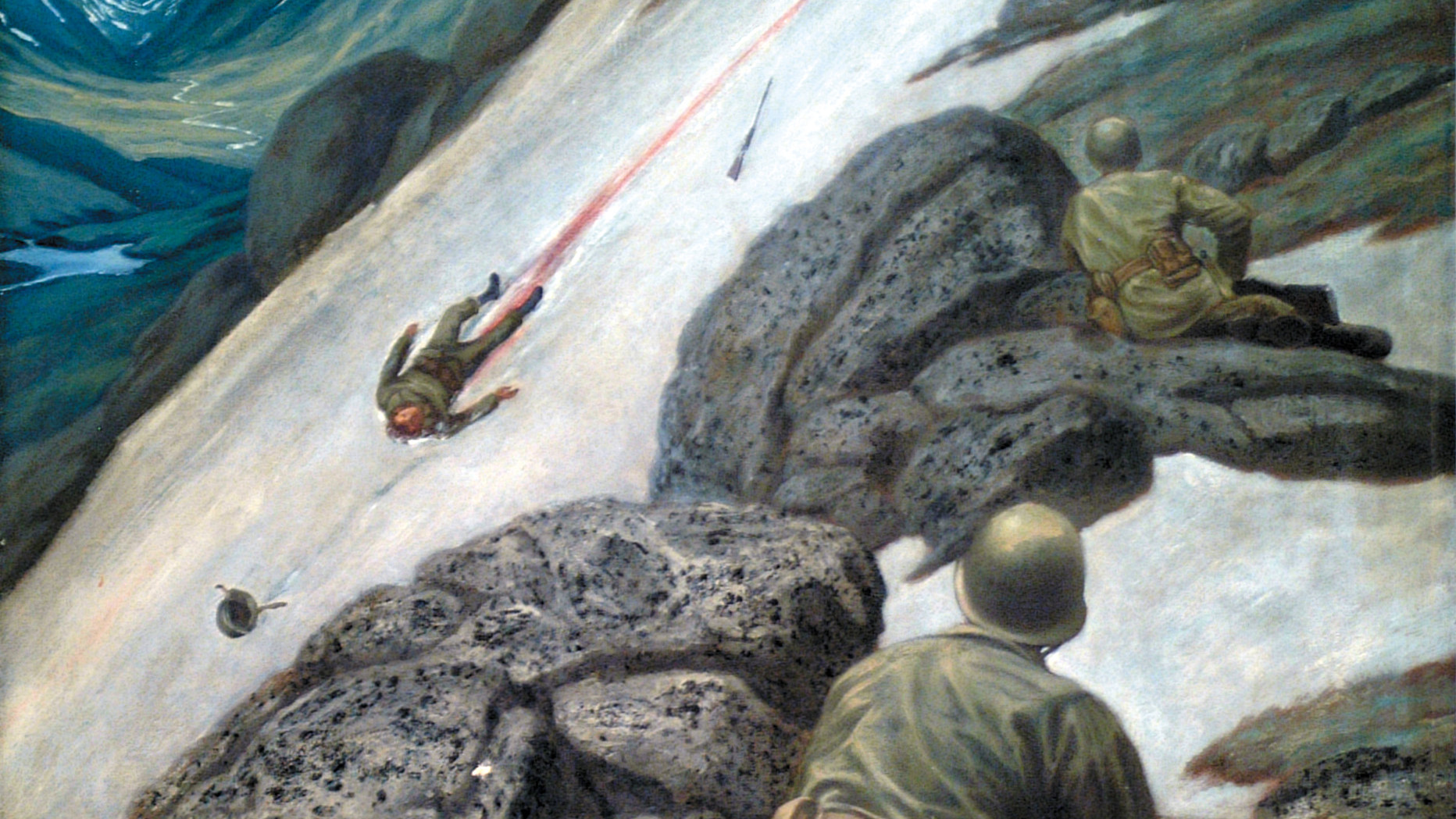

In the confusion accompanying the cataclysmic final months of the war in Germany, James miraculously escaped the hangman. Transported by the SS from camp to camp, including Flossenburg, Dachau, and Reichanau, he became integrated with the Prominenten, prominent prisoners including royalty and government leaders held as veritable hostages by the Third Reich. The war ended for James in the Tyrolian Alps on May 4, 1945 when Americans liberated him and his group.

James’s account of his five years as a German POW and his participation in a dozen escape attempts, including the “Great Escape,” is an elegantly written, self-effacing, and riveting saga of intrepidity, camaraderie, and devotion to duty. It sheds tremendous light on the human element of warfare—ranging from one end of the spectrum to the other—and provides tantalizing glimpses of Germany in its final death throes. If you read only a single volume of World War II memoirs this year, Moonless Night should be the one.

In Brief

In Brief

Six Weeks in the Sioux Tepees: A Narrative of Indian Captivity, by Sarah F. Wakefield, June Namias, ed., University of Oklahoma Press, Red River Books, Norman, 2002, 173 pp., chronology, illustrations, map, notes, bibliography, index, $14.95 softcover.

The 1862 Dakota War in Minnesota has been overshadowed by the Civil War. During this six-week Indian insurrection, over 500 military and civilian whites were killed. Another 269, mostly women and children and including Sarah Wakefield, a doctor’s wife with two small children, were taken captive. Although Wakefield was brutalized by her captors, she claimed her life was spared through the efforts of a Dakota Indian named Chaska. During the hysteria and trial following the uprising, Wakefield took the unpopular position of defending Chaska, who was one of 38 Dakotas later hanged in the largest mass execution in American history. Wakefield originally wrote her memoir in 1863. It is now republished with an excellent editor’s introduction and explanatory endnotes. This compelling account of Indian captivity helps provide an understanding of white frontier expansion and the resultant cultural clash with the Native Americans.

The Splendid Little War: The Dramatic Story of the Spanish-American War, by Frank Freidel, Burford Books, Short Hills, NJ, 2002, 246 pp., illustrations, map, bibliography, index, $18.95 softcover.

The Splendid Little War: The Dramatic Story of the Spanish-American War, by Frank Freidel, Burford Books, Short Hills, NJ, 2002, 246 pp., illustrations, map, bibliography, index, $18.95 softcover.

The Spanish-American War of 1898 was fought by the U.S. Army and Navy against Spanish forces on Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines and in surrounding waters. The technologically superior U.S. Navy ships destroyed the Spanish fleets in Manila and Santiago Bays. The Army was hampered by outdated black-powder rifles, serious equipment shortages, and control problems. It muddled its way to victory largely through the inspired leadership of junior officers and courageous troops. This highly readable narrative, first published in 1958, is an overview of the war. It focuses on what the war was like from the soldiers’ and sailors’ experiences and perspective through the (unattributed) use of extracts from memoirs and other first-person accounts. This approach shows that the conflict Ambassador John Hay called “a splendid little war” was grim, dirty, and bloody for the participants. A combination of American luck and Spanish incompetence allowed the United States to win the war and emerge as a power on the international stage.

The First, the Few, the Forgotten: Navy and Marine Corps Women in World War I, by Jean Ebbert and Marie-Beth Hall, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2002, 224 pp., illustrations, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $29.95 hardcover.

The First, the Few, the Forgotten: Navy and Marine Corps Women in World War I, by Jean Ebbert and Marie-Beth Hall, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2002, 224 pp., illustrations, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $29.95 hardcover.

This groundbreaking study dispels many misconceptions about women serving in the U.S. Armed Forces during World War I. Although women had served in the Army Nurse Corps since 1901 and in the Navy Nurse Corps since 1908, they were neither enlisted nor commissioned, although they were generally treated like the latter. In March 1917, the month before U.S. entry into World War I, females for the first time were authorized as a temporary wartime measure (that ended in 1920) to enlist in the Navy and Marine Corps Reserve.

This volume chronicles the background, requirements, and procedures for—and perceptions of—female enlistees. It also shows that these female yeomen and Marines served effectively as clerks, typists, messengers, telephone operators, and in similar positions, thus freeing males for overseas and combat service. Navy enlisted women totaled 12,000 and female Marines 305 out of a Navy force that eventually totaled 540,059. By the authors’ own account, however, especially in terms of postwar entitlements, these female veterans were not as forgotten, especially by the government, as the title implies. Generally well researched, superbly written, and interesting, this volume makes a worthy contribution to American military history.

Images of America: Fort Dix, by Daniel W. Zimmerman, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, SC, 2001, 128 pp., photographs, maps, $19.99 softcover.

Images of America: Fort Dix, by Daniel W. Zimmerman, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, SC, 2001, 128 pp., photographs, maps, $19.99 softcover.

This interesting and profusely illustrated volume is a pictorial history of Ft. Dix, New Jersey, one of 16 Army camps established by Congress in 1917 to train the influx of recruits needed for the large U.S. Army of World War I. About 200 photographs, some rare and never before published, depict the evolution and contributions of the post, beginning with its construction and the training of Army units during World War I. After World War I, Ft. Dix was used as a reserve component training center. During World War II, 10 divisions and many smaller units mobilized, trained, or deployed from Ft. Dix before shipping out. Basic training ceased at Ft. Dix in 1992, when the post reverted to its earlier role of reserve mobilization and deployment center. The interesting photographs in this volume provide a glimpse of the many activities of Ft. Dix throughout its long history, helping make the heritage of America’s soldiers more accessible to a large audience.

Harold E. Raugh, Jr.

By Any Means Necessary by William E. Burrows, Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2001, 416 pp., $26.00 hardcover

By Any Means Necessary by William E. Burrows, Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2001, 416 pp., $26.00 hardcover

William E. “Bill” Burrows is hardly a newcomer to the realm of telling stories of high technology, adventure, and espionage. Author of books like Deep Black, Exploring Space, and This New Ocean, Burrows has made a career of opening previously secret worlds to a public hungry for such tales. More importantly, Burrows is the kind of author with the courage to take on subjects previously taboo or too dangerous for conventional writers. For example, Deep Black was written years before the existence of the National Reconnaissance Office and its fleet of photographic satellites were officially acknowledged by the U.S. government. It was with this knowledge of Burrows and his books that I picked up By Any Means Necessary, expecting his usual quality read. What I got, though, was something much more rewarding.

By Any Means Necessary is the story of covert U.S. intelligence collection of communist bloc electronic communications and radar signals by aircraft during the Cold War. That subject alone is worth a volume the size and detail of By Any Means Necessary. However, what makes it a truly intriguing read is the depth to which Burrows has gone to add a human face to the many men who flew these long, dreary, dangerous, and sometimes deadly missions. During the Cold War, 16 U.S. military aircraft and over 150 American service personnel were lost to hostile action flying surveillance missions over and near the Soviet Union and other communist countries. The U.S. government usually denied the existence and nature of these missions, and always a veil of security hid the full truth of what had occurred. Very few of the downed airmen returned alive, and the actual fates of others remain shrouded in mystery following the demise of the USSR in the early 1990s.

Burrows explores all of this and more, fleshing out the men who flew the “ferret” missions, who until now have only been known to their families and friends. For many, By Any Means Necessary is their first look at the sacrifices and contributions made by pilots and crew denied by security restrictions an opportunity to stand up and be counted.

By Any Means Necessary is unquestionably the finest book yet written by Bill Burrows. In telling the story of the “ferrets” and their long-secret missions, he does his usual fine job of translating high-technology topics into language laymen can understand and even enjoy. In reaching to tell the human side of the story, though, he has gone the extra mile for the country and those craving information on their friends and loved ones. In recommending By Any Means Necessary, let it be known that this is an engrossing read, with more than a little darkness and angst to counterpoint the missions being described. Considering the 2001 EP-3 incident with the People’s Republic of China just a year past (and covered in By Any Means Necessary), this is a worthy addition to the bookshelf of anyone interested in intelligence or Cold War history. n

John D. Gresham

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments