By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

Tacfarinas, a former soldier of Rome’s Numidian cavalry, reined in his steed at the edge of the cliff with the ease of one born in the saddle. In the prime of his life, the scars of Tacfarinas’ muscled bare limbs and the arms of battle he carried marked him as a man of war. Tacfarinas surveyed the cultivated lands that sprawled from the base of the rocky slope. The winter winds had blown from the Atlantic Ocean, bringing life giving water to northwest Africa. It was the spring of ad 17, and all along the fertile coastal plains Numidian farmers reaped the harvest. Like the Numidians, Tacfarinas was a Berber, a name for the tribal people of North Africa derived from the Roman word for barbarian.

Tacfarinas knew that a lot of the Numidian grain was used by the local Roman III Augusta Legion. Stationed at the town of Ammaedara (Haidra), the III Augusta Legion needed nearly 2,000 tons per year. Even more was shipped to Rome. Tacfarinas knew the Romans well. Underneath the leopard skin draped over his shoulder, he wore a shirt of Roman mail, and a Roman spatha cavalry sword dangled at his side. The Romans had been in northwest Africa for generations of Tacfarinas’ family. The Romans had gained a permanent foothold in 146 bc, when they destroyed the city of Carthage, thus ending its Punic empire forever. From her province by the Gulf of Tunis, through war and diplomacy, Rome extended her sway over the neighboring Berber kingdom of Numidia.

Roman rule stimulated the growth of towns, agriculture, and trade. Olive, date, palm, and grape thrived on Roman suburban estates. Roman Africa, alongside Egypt, replaced Sicily as the empire’s main wheat basket. The Numidians abandoned their traditional nomadic ways and settled down to farm life. Even the roar of the lion became rare hunted and trapped, alongside other wild beasts, to die in Roman circuses.

Not everywhere, reflected Tacfarinas proudly, did the will of Rome hold sway. Away from the coastal plains, there rise the Aures Mountains, the eastern extension of the Atlas Mountains. Upon the high plateaus, Berber tribes carried on a pastoral life inherited from Eurasian horsemen, who had settled among older cultures thousands of years earlier. Their herds were plentiful; Greek historian Polybius wrote that he had seen more sheep, goats, cows, and horses in Africa than anywhere else.

The Berbers of the Aures were Tacfarinas’ tribe, the Musulamii. Among villages of kindred mountain clans, the herders traded milk, meat, wool, and leather for grain. Likewise, in times of peace, trade occurred with the larger coastal communities. Even then, however, Musulamii herds could trample and devour Numidian crops. It was the age old conflict between farmer and herder. When mountain valleys became cauldrons of heat and streams ran dry, the Berber flocks needed to find fresh growth elsewhere. The sheep of the mountain villagers were driven up to cooler higher slopes. The large herds of horses and cattle migrated toward the grazing land of the milder Mediterranean coast.

Now, where once grew wild grasses, the Musulamii came across fields of cultivated wheat. Fences, to keep out the nomads’ flocks, cut across the land. The final straw was a new Roman road from Tacape (Gabes) on the coast to Ammaedara in Musulamii territory, right across the seasonal migration routes. From Ammaedara, Rome sought to monitor the movement of the nomadic tribes. Roman patrols surveyed tribal lands to be allotted to settler farmers. Musulamii pleas for land grants that respected their traditional grazing grounds fell on deaf Roman ears.

It was Tacfarinas who, like a fire on the steppes, ignited the Musulamii discontent into a full-fledged uprising. Tacfarinas was torn between serving Rome and the plight of his own Musulamii people. He deserted, forsaking his chance of obtaining citizenship and a desirable life within the empire. Long ago, the mountain tribes had formed a barrier to the extension of the Carthaginian Empire. Perhaps they could do the same with the Roman Empire.

At first Tacfarinas led no more than “vagabonds and marauders,” wrote Roman historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus. But Tacfarinas trained his men in Roman discipline and employed them in guerrilla attacks. Some of his men, such as his personal guard, he equipped like Roman soldiers. Tacfarinas eventually became chief of the Musulamii. His daring exploits won over more tribes. From south of Numidia, nearest to the desert, came the Gaetulians, old allies of the Musulamii, and from the coast, near Gigthis, a large tribe of like-minded Cinithii.

Most welcome by Tacfarinas were the Mauri (i.e., Moors) from neighboring Mauretania, the vast tribal kingdom that for 200 years encompassed western Algieria and all of Morocco. Mazippa, leader of the Mauri, revolted against his own king, Juba II, who was loyal to Rome. When Rome annexed the Kingdom of Numidia into its African province in 25 bc, Juba II was handed the heirless, Roman-allied Kingdom of Mauretania in compensation. Like the Romans, Juba encouraged agriculture and trade. With their pastures lands transformed to farms, the plight of Mauri nomads was the same as that of the Musulamii. At that point, the Mauri sought vengeance through raiding.

The governor of Africa Proconsularis, Proconsul Marcus Furius Camillus, prepared to lead the III Augusta Legion and auxiliaries, approximately 10,000 troops, against the rebels. Camillus hailed from a prestigious family, the Furii. Roman tradition alleged that in the days of Rome’s infancy, Camillus’ namesake liberated Rome from the Gauls. Since then, martial fame passed to other prominent families. Nevertheless, Camillus knew well enough to crush the rebellion before it grew even larger. Neither could he underestimate the enemy. The fate of Proconsul Cornelius Lentulus, who was slain before the last great tribal uprising when he marched too deep into the desert in 3 ad, served as a grim reminder.

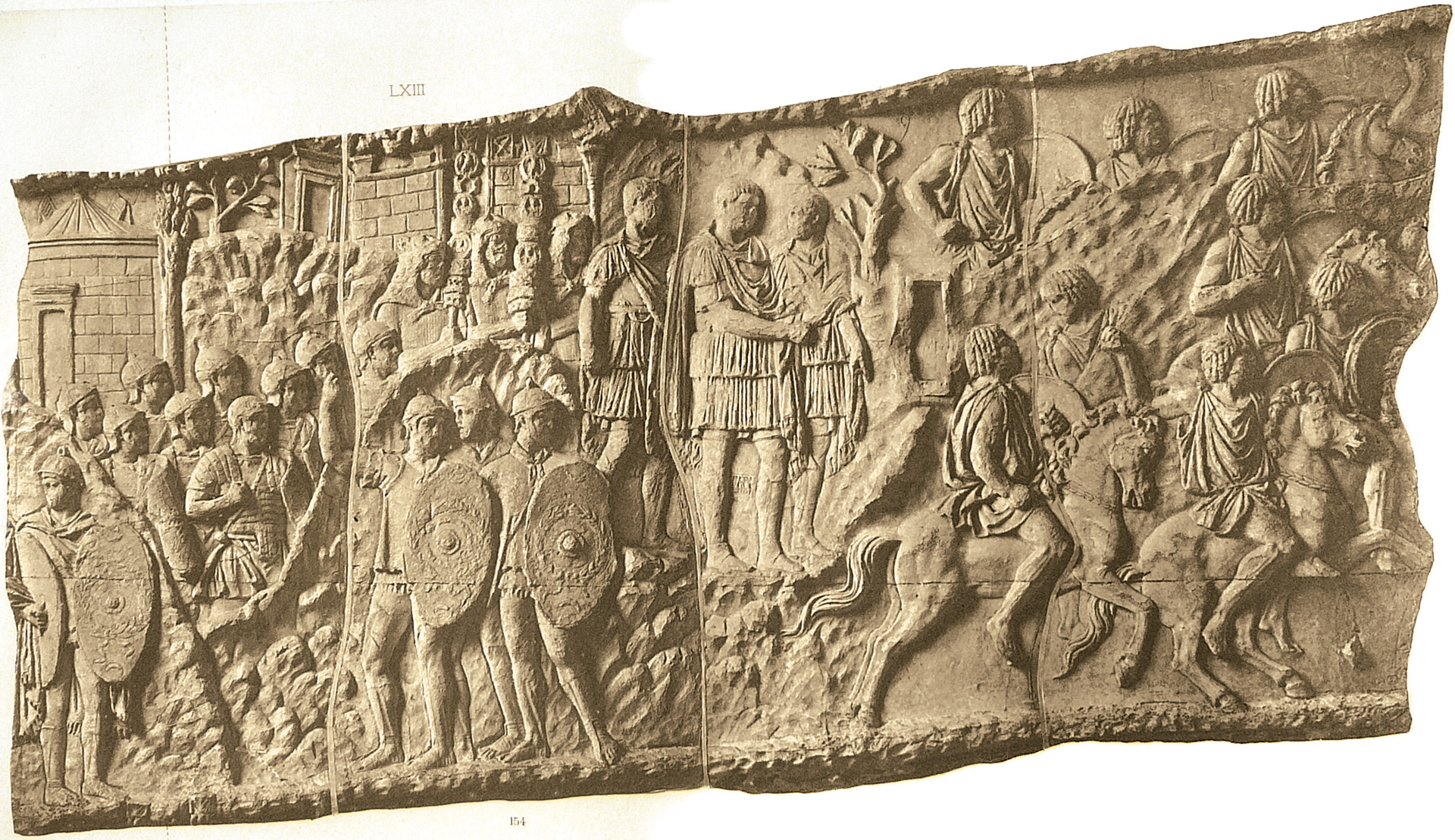

In the looming battle, Camillus counted on his legionaries’ loyalty, élan, and the experience of his centurions, some of whom spent their entire career fighting the hill tribes. Originally recruited from Latinized Celts of Roman Gaul and from Italians, the 60-year-old III Augusta Legion had since received replacements from all over the empire. The culturally diverse legionaries found solidarity in their coveted Roman citizenship and in the Latin tongue, in which they all could converse.

Camillus may well have mulled over Rome’s long association with the Berbers. The nomadic Berbers traditionally provided a source of light cavalry recruits, having fought beside the legions for hundreds of years. However, as Roman presence in Africa grew, the nomads increasingly became a menace to peace in the region. There were African campaigns and Roman triumphal awards in 34, 33, 28, 21, and 19 bc. During the border strife in ad 5-6 that followed Lentulus’ death, the Musulamii revolted in support of the Gaetulians. That tribal coalition met defeat at the hands of King Juba II and Roman troops.

Clad in sheepskins and simple tunics, armed with small shields of hide and broad-bladed javelins, the Musulamii excelled at skirmishes, but they had little chance in a set-piece battle against legionaries armed to the teeth. Tacfarinas felt otherwise. His larger army, approximately 20,000 strong, with Roman-style elite detachments, was ready to confront the Romans.

Somewhere on the steppes, the two armies met. Camillus deployed the III Augusta Legion in the center with his auxiliaries on the wings. The auxiliary light infantry cohorts, Iberians and Thracians, and the light cavalry squadron of Numidians, were easily routed by the weight of Musulamii numbers. The legionaries held their ground; their javelin barrages ripped into the lightly armed ranks of assaulting Berbers.

Behind their wall of large body shields and tortoise formations, the Romans weathered any enemy javelin barrage fairly unscathed. Attempts to break the Roman ranks by cavalry charge floundered. Neither Berbers nor their horses would hurl themselves onto an unflinching shield wall. Tacfarinas’ Roman-style troops must have been too few to make a difference and despite his best efforts would not have been able to equal the legionaries in discipline. With the bulk of Tacfarinas’ infantry remaining hopelessly outmatched against legionaries in mail hauberks, iron-bound shields, and bronze helmets, the Berbers reverted to hurling javelins, shouting taunts, and abortive charges. This left Tacfarinas no choice but to withdraw, leaving Camillus victorious.

Emperor Tiberius Claudius Nero was delighted by the renown the victory restored to Camillus’ lineage. Tiberius awarded Camillus a laureled statue and the ornaments of a triumph. The immense prestige of an actual triumph was reserved for members of the imperial family. The emperor’s optimism proved unfounded. As early as the next year, ad 18, Lucius Apronius, Camillus’ replacement, again found Roman Africa beset by Tacfarinas’ guerilla raids. Tacfarinas initially concentrated his forays around Ammaedara and the surrounding Aures. Of Mazippa’s Mauri, there is no more mention, apparently leaving Tacfarinas and his Musulamii to fight on alone.

By the River Pagyda, Tacfarinas encircled a fortified marching camp held by a legion cohort. Considering it disgraceful to be besieged by the Berbers, the fort’s veteran commander, Decrius, boldly deployed his cohort outside the ramparts. Unfortunately, he misjudged the steadfastness of his soldiers, who broke before the Musulamii onslaught. Decrius flung himself into the hail of enemy javelins, hoping to gain time for some of his men to escape. Decrius cursed the standard bearers, who turned their backs on Tacfarinas’ irregulars. Bleeding from a wound to his body, with blood oozing from a pierced eye, Decrius fought until overcome by his foes.

More shocked by the Roman dishonor than he was worried about Tacfarinas’ success, Lucius Apronius revived an ancient and rarely used punishment known as decimation. The survivors of the disgraced cohort drew lots; every 10th legionary was flogged to death in front of his comrades.

Tacfarinas next assaulted the fort at Thala, 16 miles northeast of Ammaedara. The legion vexillation (detachment) at Thala was past its youthful prime, but its 500 legionaries were battle-hardened veterans, who repulsed the Musulamii attack. During the battle, one of the soldiers, Helvius Rufus, saved the life of a Roman civilian. Apronius rewarded Rufus with an honorific chain and spear. Tiberius added the highest military decoration, the citizen’s oak wreath, and admonished Apronius for not adding this reward himself.

His demoralized men lacking the patience for siege warfare, Tacfarinas resumed his raiding, descending from the Aures to attack the richer coastline. By ad 20, the sheer amount of loot forced him to establish a semi-stationary base.

Tacfarinas’ hostilities had become such a serious threat that Roman Africa had been reinforced with a second legion, the veteran IX Hispana Legion transferred from Pannonia. Nevertheless, the Roman governor’s son, Lucius Apronius Caesianus, still needed his cavalry, auxiliary light infantry, and swiftest Roman legionaries to engage the Berbers and win a victory.

Tacfarinas and his Musulamii retreated into the mountains that served as their base. In that setting, they were able to rest and plan future raids. They took shelter in clay brick huts and caves, where terraced fields were interspersed with meadows and forests of oak and pine.

In ad 21, the Roman Senate met within its sacred hall to hear a letter from the emperor. Only the previous year, more triumphal ornaments and another laureled statue had been awarded to Apronius for his son’s victory against Tacfarinas. The emperor wrote that Tacfarinas wreaked havoc in Africa. To Tiberius’ displeasure, the Senate deferred upon him the task of choosing an experienced and physically fit governor to deal with Tacfarinas.

Tiberius bid them to pick between Marcus Aemilius Lepidus and Quintus Junius Blaesus. Lepidus ardently pleaded excuses of his ill health, young children, and marriageable daughter. The senators thought that Lepidus was only bowing to the inevitable favorite Blaesus. Blaesus was the uncle of Lucius Aelius Sejanus, who was the influential Prefect of the Praetorian Guard. Enjoying the flattery from senators wishing to curry Sejanus’ favor, Blaesus pretended not to be interested before giving in to accept the appointment.

Backed by reinforcements from the interior of northern Africa, Tacfarinas felt strong enough to parley with Rome. The Musulamii envoys traveled to Rome where they demanded land in exchange for peace. If this was not given, then there would be endless war. The Musulamii appeals were in vain. “No personal or national slur” ever provoked Tiberius more than Tacfarinas, who “behaved like a hostile sovereign,” wrote Tacitus. Not even Spartacus was granted conditions for his surrender.

To undermine Tacfarinas’ popularity, Blaesus received permission to pardon surrendering rebels. Only their leader was to be captured by any means available. Publius Cornelius Lentulus Scipio, who commanded the IX Hispana Legion, was to guard the approaches to the coastal trading city of Leptis Magna in Tripolitania, the eastern portion of Africa Proconsularis. The city’s riches, derived from the export of olive oil, already had suffered from Tacfarinas’ raiders, who received shelter from the Saharan Garamantes. Westward, Blaesus’ son was ready to protect Cirta and her outlying settlements, where merchants from Italy and Greece long ago settled to trade for Numidian grain. Between Blaesus’ son and Scipio, Blaesus led the offensive with selected detachments of the III Augusta Legion in the Aures.

Blaesus split up his forces with battle-proven company commanders holding key positions, such as mountain passes that gave access to water. Continuing the offensive into the winter, Blaesus built a new chain of forts closer to the desert frontier from Ammaedara westward into the Aures. Cavalry patrols attuned to the desert hounded Musulamii raiders and undoubtedly plundered and massacred civilians of hostile villages. Those not slain felt the clasp of Roman shackles, including Tacfarinas’ brother. Only the Sahara Desert loomed as a last refuge when the Roman incursions suddenly stopped. In ad 23, judging the Musulamii subdued, Blaesus inexplicably called a halt to his operations and withdrew.

Among townsfolk and villagers friendly to the Romans, the news of Blaesus’ departure was ill received. Tacfarinas and all too many of his raiders remained at large. Tiberius, in contrast, once more considered the war concluded. He even removed the IX Hispana Legion from Roman Africa. Blaesus’ replacement, Governor Publius Cornelius Dolabella, dared not object for fear of the emperor’s wrath. Tiberius allowed the soldiers to hail Blaesus as victor, an honor that had been granted on certain occasions by Augustus, and rewarded him with triumphal ornaments and a laureled statue.

The tribes saw in the departure of the IX Hispana Legion a show of Roman weakness. Even from Roman Africa brigands flocked to Tacfarinas’ army. Tacfarinas quickly recovered his losses, and in ad 24 he returned to plunder villages and trade routes. Tacfarinas’ army was further strengthened by new Mauri reinforcements. Juba II, who died in ad 23, had passed his kingdom to his son, Ptolemy. Ptolemy, who was 25 years old, was deemed “too young for responsibility,” according to Tacitus. Ptolemy’s household and kingdom fell under the influence of ex-slaves, whose tyranny caused numerous Mauri to join Tacfarinas’ army.

With the departure of the IX Hispana Legion from Leptis Magna, the Garamantes also made common cause with Tacfarinas. Although rumors exaggerated their numbers and their king declined to join his desert raiders in battle, their fortified capital at the oasis of Garama (Germa) provided a safe haven for Tacfarinas. Tacfarinas spread the rumor that other peoples also were breaking free and that Rome was gradually evacuating Africa. The remaining garrisons could be surrounded and taken, that is, if all fought together.

Flames roared, engulfing the crumbling walls of the fort of Auzea, which fell to Tacfarinas. Emboldened, Tacfarinas placed the town of Thubuscum under siege. With all available troops Dolabella hastened to Thubuscum’s aid. When Tacfarinas’ raiders fled at the first Roman advance, Dolabella grasped the initiative. He set up strongpoints and ruthlessly executed any Musulamii chiefs who were contemplating rebelling. Roman generals led four legionary columns, from which Ptolemy’s Mauri officers led antipartisan raids. Dolabella personally directed his field commanders and received any news of Tacfarinas’ whereabouts on the spot. Before long, patrols reported that Tacfarinas was encamped at Auzea. Thick and extensive woods surrounded the area. Dolabella wasted no time sending light infantry and cavalry against the rebels, although he kept their goal secret from others.

The rising sun flared red above the ruined walls of Auzea. Silence lay over the fort, broken only by the occasional stomp and snort of Berber horses. Abruptly, the din of trumpets shattered the calm. Sleepy-eyed tribesmen, startled and shocked, awoke to find Romans and hostile Mauri overrunning the encampment. Roman infantry in close order descended upon the camp. Cavalry galloped around the flanks. The Musulamii were completely overwhelmed and caught unarmed. They offered little resistance and fled in disorder. The Romans, frustrated by long fruitless chases, indulged their thirst for vengeance.

His way to freedom barred, Tacfarinas did not cower. The Romans killed all of Tacfarinas’ bodyguards, and they took his son prisoner. Tacfarinas’ capture also seemed assured. The Roman infantry surrounded him and pressed closer. A wall of shields faced him, bristling with spears, but Tacfarinas had no wish to feel Roman shackles on his wrists and to be thrown into some dank dungeon and then paraded and executed before a cheering mob. Like a cornered lion of the desert, Tacfarinas hurled himself onto the Roman spearheads. His death “had cost the Romans dearly,” wrote Tacitus.

Tacfarinas’ death induced the Garamantes to send a peace delegation to Rome. The tribesmen were an anomaly in the imperial city, but more of a stir was caused by Tiberius’ refusal to honor Dolabella’s request for triumphal honors. Tacitus blamed Tiberius’ pandering to Sejanus, accusing the emperor of not wanting to belittle Blaesus’ achievements. The slight had the opposite effect, putting Blaesus in a poor light while Dolabella’s reputation grew.

Ptolemy’s help was not forgotten. The young Mauretanian king received a visit from a Roman senator, who presented ceremonial gifts and proclaimed Ptolemy as king and friend of Rome. Sixteen years later, in ad 40, Ptolemy visited Rome and its new emperor, who was also Ptolemy’s cousin, Gaius Caligula Germanicus. Caligula gave Rome’s old ally a lavish welcome but was outraged over Ptolemy’s stunning entrance at a gladiatorial show, sporting a purple cloak that “attracted universal admiration,” according to historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus.

The megalomaniac Caligula ordered Ptolemy’s execution and thereafter annexed Mauretania into the empire. It took Caligula’s successor, Claudius, several years to put down the subsequent tribal revolt. Only heatstroke and thirst suffered in the red gravel sands of the Sahara forced the Romans to call off their pursuit of rebellious Mauri. It was the last great revolt for two centuries.

At the beginning of the 2nd century ad, even the Musulamii, given generous land grants, settled down and abandoned their pastoral ways. During the reign of Septimius Severus (ad 193-211), Roman territory in North Africa reached its greatest extent, brought to a halt only by the Sahara. The III Augusta Legion remained the sole permanent legion stationed in North Africa until the beginning of the empire’s collapse in the 4th century ad.

The nomadic Berbers probably never had any realistic chance of avoiding Roman dominion. Remnants of the classical Berber culture nonetheless outlasted the empire. Even today, Berber children excitedly greet Westerners who visit their hill villages with the cry of “Arrumi,” meaning “Roman.” Two thousand years ago, for eight long years, Tacfarinas led their ancestors to defy and at times even defeat Rome’s renowned legionaries.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments